Vatican rejects ‘Doctrine of Discovery’ justifying colonialism

After decades of demands by Indigenous people, Vatican ‘repudiates’ theories that backed colonial-era seizure of lands.

The Vatican has rejected the “Doctrine of Discovery”, a 15th-century concept laid out in so-called “papal bulls” that were used to justify European Christian colonialists’ seizure of Indigenous lands in Africa and the Americas.

In a statement on Thursday, the Vatican’s development and education office said the theory (PDF) – which still informs government policies and laws today – was not part of the Catholic Church’s teachings.

It said the papal bulls were “manipulated for political purposes by competing colonial powers in order to justify immoral acts against Indigenous peoples that were carried out, at times, without opposition from ecclesiastical authorities”.

“In no uncertain terms, the Church’s magisterium upholds the respect due to every human being,” the statement reads. “The Catholic Church therefore repudiates those concepts that fail to recognize the inherent human rights of Indigenous peoples, including what has become known as the legal and political ‘doctrine of discovery’.”

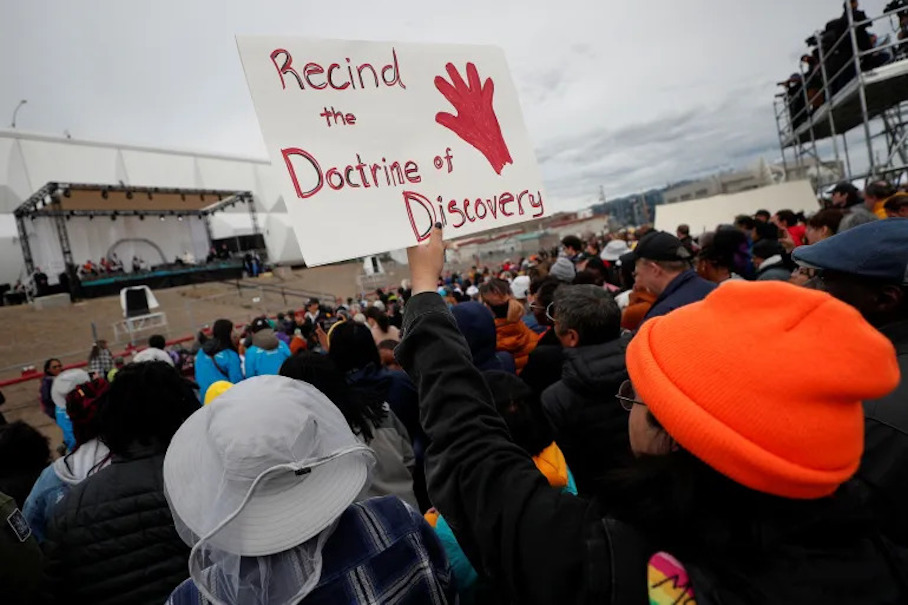

For decades, Indigenous leaders and community advocates had urged the Catholic Church to rescind the Doctrine of Discovery, which stated that European colonialists could claim any territory not yet “discovered” by Christians.

The papal bulls played a key role in the European conquest of Africa and the Americas, and their effects are still felt by Indigenous people.

Calls to rescind the Doctrine of Discovery grew louder last year when Pope Francis made a trip to Canada during which he apologised for the Catholic Church’s role in widespread abuses that took place at so-called residential schools.

Between the late 1800s and 1990s, more than 150,000 Inuit, First Nation and Metis children across Canada were taken from their families and communities and obligated to attend the forced-assimilation institutions, which were rife with physical, psychological and sexual violence.

The Haudenosaunee External Relations Committee said at the time of the pope’s residential school apology that more action was needed from the church – notably, the revocation of the papal bulls.

“An apology to Indigenous Peoples without action are just empty words. The Vatican must revoke these Papal Bulls and stand up for Indigenous Peoples’ rights to their lands in courts, legislatures and elsewhere in the world,” the committee said in a July 2022 statement.

Indigenous leaders welcomed Thursday’s Vatican statement, even though it continued to take some distance from acknowledging actual culpability.

Phil Fontaine, a former national chief of the Assembly of First Nations in Canada who was part of the delegation that met with Pope Francis at the Vatican before last year’s trip and then accompanied him throughout, said the statement was “wonderful”.

He said it resolved an outstanding issue and now put the matter to civil authorities to revise property laws that cite the doctrine.

“The Holy Father promised that upon his return to Rome, they would begin work on a statement which was designed to allay the fears and concerns of many survivors and others concerned about the relationship between their Catholic Church and our people, and he did as he said he would do,” Fontaine told The Associated Press news agency.

“Now the ball is in the court of governments, the United States and in Canada, but particularly in the United States where the doctrine is embedded in the law,” he said.

“Today’s news on the Vatican’s formal repudiation of the Doctrine of Discovery is the result of hard work and advocacy on the part of Indigenous leadership and communities,” Canadian Justice Minister David Lametti wrote on Twitter. “A doctrine that should have never existed. This is another step forward.”

The Doctrine of Discovery was cited as recently as a 2005 US Supreme Court decision involving the Oneida Indian Nation and written by the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

On Thursday, the Vatican offered no evidence that the three papal bulls (Dum Diversas in 1452, Romanus Pontifex in 1455 and Inter Caetera in 1493) had themselves been formally abrogated, rescinded or rejected, as Vatican officials have often said.

But it cited a subsequent papal bull, Sublimis Deus in 1537, that reaffirmed that Indigenous peoples should not be deprived of their liberty or the possession of their property, and were not to be enslaved.

Cardinal Michael Czerny, the Canadian Jesuit whose office co-authored the statement, stressed that the original papal bulls had long ago been abrogated and that the use of the term “doctrine” — which in this case is a legal term, not a religious one — had led to centuries of confusion about the church’s role.

The original papal bulls, he said, “are being treated as if they were teaching, magisterial or doctrinal documents, and they are an ad hoc political move. And I think to solemnly repudiate an ad hoc political move is to generate more confusion than clarity”.

He stressed that the statement was not just about setting the historical record straight, but “to discover, identify, analyse and try to overcome what we can only call the enduring effects of colonialism today”.

Michele Audette, an Innu senator who was one of the five commissioners responsible for conducting the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls in Canada, told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation that the announcement left her in disbelief.

“It’s big,” she said in an interview on CBC Daybreak. “That doctrine made sure we did not exist or were even recognised … It’s one of the root causes of why the relationship is so broken.”