Anti-War Initiatives Led by Indigenous Peoples in Russia are Inherently Anti-Colonialist

Anti-war movements in Russia immediately appeared at the onset of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Notably, these initiatives were and are by and large driven by preexisting feminist organizations (The Social Democratic Alternative, Eighth Initiative Group, Eve’s Ribs, the Agasshin Project, and the Feminist Translocalities Project to name a few) and Indigenous and ethnic minority groups founded in direct response to the war. While currently there is no sole, centralized movement uniting the country’s numerous Indigenous Peoples and ethnic minorities, the appearance of various anti-war organizations, media accounts, and content, and action points to a rather unprecedented impetus of collaboration and solidarity focused on condemnation of the Russia state’s actions.

Further unparalleled is the overt and widespread presence of anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist sentiment as activists and laypeople alike criticize Russia’s attack on Ukraine and probe into the federation’s enduring issues of coloniality in quotidian life (racism, discrimination, xenophobia, and the violence they encourage). The invasion of Ukraine is not new or covert; rather, it represents the next steps in a long and ongoing history of Russian colonial understanding of a sovereign Ukrainian nation and distinct Ukrainian culture as a threat needing mitigation. These anti-war, staunchly anti-colonialist, and Indigenous-led initiatives are small in number but increasingly outsized in influence. From the use of native languages in anti-war campaigns to overt castigation of Russian chauvinism, these initiatives point to resistance to both the ongoing war and colonial policy. Their importance cannot be overemphasized since their efforts contribute to a better understanding of, and subsequently, better capacity for dismantling Russian coloniality.

Russia’s claims that it is fighting “neo-Nazis” in Ukraine is a blatant distortion of history, and the irony of this claim is far from lost on many Indigenous Peoples of Russia who grew up in a society steeped in Russian colonialism and who witness growing ethnic Russian nationalism (often abetted by right-wing and neo-Nazi sentiment) on societal and institutional levels (e.g., ethnic Russian nationalism enshrined in the federal constitution since 2020).

Anti-war movements like the Free Buryatia Foundation––the first anti-war initiative started in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and on behalf of an ethnic group––emphasize this paradox and use the current conflict to advocate for a reckoning with historic racism and imperialism within Russia’s own borders. The objective of The Free Buryatia Foundation (Buryats Against the War) is twofold––to fight against the war on Ukraine and to “solve the problem of racism and xenophobia in Russia”. Founder and president of the fund, Alexandra Garmazhapova, says such an organization was needed for a number of reasons: the disproportionate number of Buryat soldiers dying in the war, the overrepresentation in media of Buryats as the main perpetrators of violence, and the latent systemic factors that usher Buryats into military service.

“Our region has been the leader in losses since the very beginning of the war, and it was important for us to declare that we are Buryats, and we are against the war. We consider the war with Ukraine xenophobic, because if Russia had a tolerant society, the idea of ‘denazification’ of Ukraine…would not find support among Russians. The Indigenous Peoples of Russia have been and are being subjected to ‘denazification’, which in reality is complete Russification. We understand what it’s like to have your language and culture banned… Residents of ethnic republics who go to Moscow and St. Petersburg face xenophobia and racism… But at the same time, military personnel from [the ethnic republics] are sent to Ukraine to protect the ‘Russian world’,” Garmazhapova said in an interview in July.

The Free Buryatia Foundation tracks statistics on losses during the war, provides legal advice to help military personnel terminate their contracts, shares credible information to combat propaganda and misinformation, and strives to prevent Russian servicemen from going to Ukraine. The organization is very active on social media sites and regularly collaborates with specialists, activists, and other anti-war initiatives on live-streamed discussions, data collection and sharing, and crowdsourcing.

Most of the Free Buryatia Foundation’s team resides outside the Russian Federation, which shields them from Russia’s growing restrictive legislation, namely “fake news” laws, which criminalize the dissemination of false information about the Russian army and is used by the state to censor, detain, and imprison those who oppose the war. For that reason, there are no large-scale Indigenous-led anti-war organizations or groups based in Russia. Disparate groups and media accounts exist though they tend to maintain anonymity and much of their activism work is shared or takes place on Instagram (only accessible with use of a VPN) and Telegram. These include, but are not limited to the Sakha Pacifist Association, New Tuva Movement, and Asians of Russia (which existed prior to the war but shifted its focus to information about the war and protests), which share information specific to their respective regions in addition to sharing information among each other.

Indigenous individuals are actively engaged in anti-war actions though they are targeted by the Russian Federal Security Service and the Center for Combating Extremism (unit in the Ministry of Internal Affairs). The social media pages for various groups often crowdsource funding these activists need for legal aid. While the groups are not organized or affiliated, through their sharing of each other’s posts and through collaborations, they’re forming a kind of network––one that is able to exist under the current Russian state. Through posts on social media are seemingly low-impact, these groups are harnessing social media as a tool to disseminate information restricted by the state and state-run media and building networks on platforms that are relatively accessible.

There is no single position towards the war among Russia’s different Indigenous groups. These groups are often asked how individuals, who carry out demonstrations with signs saying “Tuvinians against the war”, or nameless admins, by using names such as Sakha Pacifist Association or New Tuva Movement, are able to speak for an entire people group. “These action[s] raise the rebellious spirit of the people. [They’re] very important demonstrations and actions for the entire people, as well as a message to the whole world,” wrote sakha_vs_war. The evocation of one’s nationality or cultural background is yet another tool for appealing to the public. The state and regional governments also utilize this tool in their co-opting of national cultures broadly, and of organizations such as the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) and the Buddhist Traditional Sangha Center of Russia specifically, in support of hostilities against Ukraine. Identity, language, and culture are effective tools for anti-war movements in this particular case as initiatives consistently underline the imperial nature of this current war.

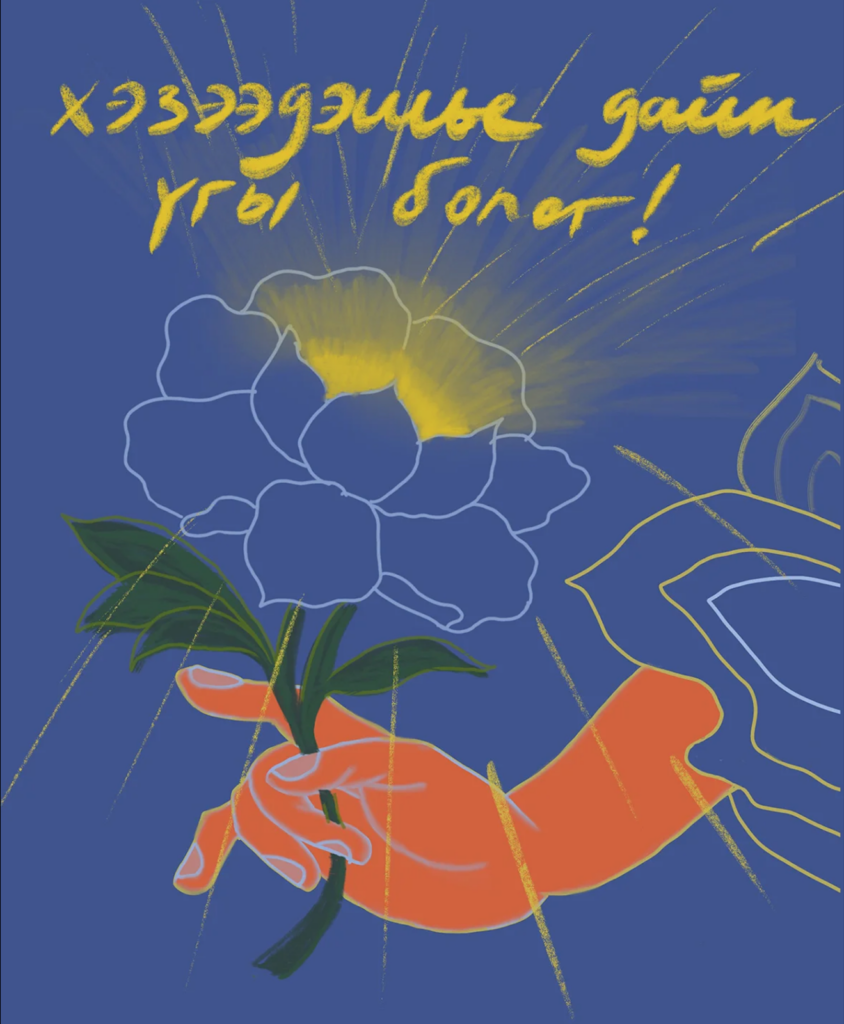

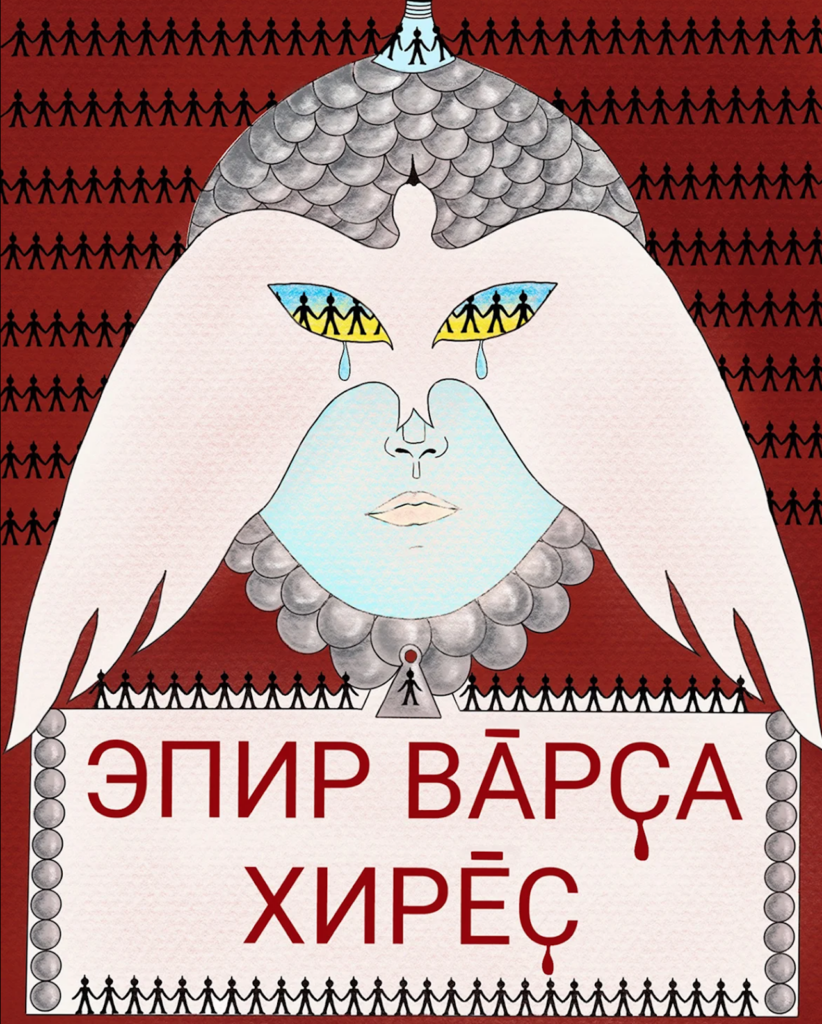

Given Russia’s history and continuing legacy of colonial language policy inherited from the Russian and Soviet empires (which systematically afforded/s primacy to the Russian language at the expense of native languages), anti-war slogans in Indigenous languages are part of reclamatory cultural education which is, at its core, anti-war as it is a struggle against colonialism. The struggle around national languages in Russia is inextricably tied to state-sanctioned xenophobia and Russian supremacy. State language policy has become increasingly restrictive on native language education as Putin proclaimed in 2017 that Russian “the natural spiritual framework of the country” and that “everyone should know it”. Then, in 2018 three amendments were made to Law No. 273 “On Education in the Russian Federation,” which made Russian language learning compulsory at the expense of native languages. National or republican sovereignty movements of non-Russian, and overwhelmingly Indigenous, ethnic groups are thus intimately intertwined with language and cultural sovereignty, making language and culture significant areas the state and its security forces carefully scrutinize. Therefore, with this context, struggles for regional authority or autonomy and the anti-war struggle are innately linked.

For many activists, printing and disseminating anti-war messages in Indigenous languages is not only symbolic of the resistance against the colonial Russian state, but also a rallying call to compatriots who might support the war or who do not openly oppose it. The Agasshin Project published a series of anti-war posters in Indigenous/national languages created by speakers of the languages (Buryat, Kalmyk, Udmurt, Chuvash) since anti-war activities in Indigenous languages “can be instruments of resistance to both the current war and colonial politics”. Aikhal Ammosov, a Sakha musician and activist, has been tried twice and is awaiting a third trial for his anti-war picketing and performances in Sakha, Russian, and English. Ammosov was first fined for “hooliganism”, then for “discrediting the Russian armed forces”, and he currently awaits trial and could possibly face up to three years in prison for his most recent art performance involving a banner reading “Yakutian Punk Against WAR”.

Following Russia’s February 24, 2022 invasion of Ukraine, activists around the world began publishing texts about colonialism, racism, and violence in Russia with fervor. Though these activists and groups are far from monolithic and cater to regional, historical, and culturally specific needs, these ideas spread and grow horizontally across the sphere of Russian influence, allowing for grassroots collaboration, collectivization, and support to grow.