Prologue: How Our Indigenous North Was Fractured

I would like to express my gratitude to those who proposed the idea of producing this series and who discussed and brought this idea to life. And many thanks for the invitation to share my thoughts on the ongoing processes that impinge upon scientists, Indigenous people, and others who have been involved in cooperation in the Arctic for many years.

What happened on February 24, 2022, was a true blow to the global community. The death and destruction that Russia has brought onto Ukraine came as a shock to all normal people. Yet even though so many experts and politicians did not believe that such a scenario was possible, it was clear that war was a “natural” continuation of the existence of the Putin regime. It doesn’t matter with whom it will fight and who it will declare its ‘enemies’ – whether it be Russia’s civil society or Moldova, Kazakhstan, or the Baltic countries. Ukraine’s bad luck was daring to choose its own path …

Of course, this war could not help but reverberate in the so-called ‘international’ Arctic community. It was here where cooperation and friendship with Russia was mostly successful, where all parties recognized the Arctic as a ‘territory of dialogue’, where so many bilateral and multilateral ties developed, and where the Arctic Council emerged and flourished as an institution of collaboration and discussion.

2.

An active participant in many processes in the Arctic, I fully acknowledge these developments. We, the Indigenous people of Russia, achieved many important results from these processes – including equal participation in the Arctic Council and involvement in various international scientific and research projects.. In turn, such developments gave us numerous opportunities to negotiate with the Russian government regarding respect for our legal rights and interests. The Russian government was forced to act to seek solutions to our issues and challenges, being fully aware that the Indigenous people of Russia had a voice at the international level that certainly would be heard and supported.

As Arctic cooperation developed in scientific research — for instance, in the areas of safe navigation and biodiversity — cooperation among Indigenous peoples also thrived. From the very beginning the solidarity of the Arctic’s Indigenous peoples was exceptionally high. I recall how in the mid-1990s a Canadian delegation of Canadian government officials and Inuit representatives visited Russia. Vice-President of the ICC (Canada) Violet Ford led the Inuit delegates. The delegation’s mission was to meet with the Indigenous people of Russia and discuss ideas for cooperation. Kamchatka was one of the regions the Canadian delegation visited. Looking at the planned agenda, the Inuit visitors were surprised to see that their ‘business’ program in Kamchatka was full of various kinds of entertainment – visiting volcanoes, geysers and the famous Paratunka spa resort, attending concerts… Absent were any visits to Indigenous communities and there was but one scheduled meeting with Kamchatka Indigenous people.

Puzzled, the Inuit guests from Canada asked the Indigenous representatives from Kamchatka whether they had agreed with the program. It turned out that Russian authorities in charge of the program had ignored the proposals of the people of Kamchatka. Inuit leader Violet Ford demanded that the program be changed to include the proposals of the local Indigenous people. To that, Canadian government officials demurred, responding that they were only ‘guests,’ with no right to request a change to the program. ’Well,’ retorted Violet Ford (I paraphrase here), ‘in this case the Inuit would return home. We won’t participate in an event that violated the rights of Indigenous people of Russia.’ Discreet negotiations ensued, during which the program was changed to include the proposals of the Indigenous people of Kamchatka.

Once at an Arctic Council meeting in the late 1990s, representatives of RAIPON (Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East) raised the issue of violations of the rights of Indigenous people of Russia. The Russian government officials flatly declined to discuss any such violations. I recall how Leif Halonen from the Sámi Council and

Akkalyuk Lynge from ICC immediately took our side and demanded explanations from the Russian officials on the issues raised by the RAIPON representatives.

I recall yet another remarkable incident toward the end of 2001, when the RAIPON delegation became part of the Russian official delegation at negotiations between Russia and Canada. These negotiations were led by the heads of government of two countries. It was literally on the eve of the meeting when we at RAIPON received a call from the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Canada, asking who from RAIPON would be taking part. We didn’t even know about these upcoming negotiations! To our surprise, we were requested to go to the Canadian Embassy right away to get our visas and to fly to Ottawa the next day. Canadian officials explained that if we were to refuse, a huge political scandal would occur. The Canadian public had already been informed by media that for the first time at interstate negotiations between Canada and Russia, Indigenous peoples would not only be the topic of negotiations but active participants in these negotiations. If representatives of Russia’s Indigenous peoples were not part of the official Russian delegation, Canada’s Indigenous representatives might simply walk out in protest. We participated in the meetings and had many productive discussions and agreements with our Inuit and First Nations counterparts.

I also took advantage of this situation to again draw the attention of the Russian authorities to the problems of Indigenous people and their resolution at such a high level. At a press conference of prime ministers, I publicly asked the Chairman of the Russian Government, Mikhail Kasyanov:

“Dear Mikhail Mikhailovich, you very correctly noted that Russia and Canada have a lot in common and similarities. You also said that Canada has many achievements and much experience in issues regarding the development of Indigenous peoples. So why doesn’t the Russian government adopt this experience and begin to implement it, based on Russian realities and Russia’s international obligations?”

To that Prime Minister Kasyanov responded: “I agree with you. Let’s you and I meet after returning home.”

That meeting took place, and we agreed to create a roadmap for resolving the issues of the Indigenous peoples of the Russian North. Such work indeed started, and was quite productive. Unfortunately, however, the situation did not last long. At the beginning of 2004 the Kasyanov government was dismissed, and he lost his position.

And another great sign of circumpolar solidarity with the Indigenous peoples of Russia was the appeal of the Senior Officials of the Arctic Council to the Russian government, when in 2012 the Russian Ministry of Justice decided to suspend the activities of RAIPON. This, and many other similar instances, helped the Indigenous peoples of Russia to conduct equal negotiations with the Russian government and build partnerships with them.

I recollect these stories to illustrate how Arctic cooperation up to a certain point had been very important and progressive.

Of course, it was Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine on 24 February 2022 that was the turning point in making continued cooperation in the Arctic impossible. Nonetheless, for the Indigenous people of Russia, curtailment of cooperation started much earlier. In 2013, the Russian government and the FSB service seized RAIPON — and then turned it into a weapon against independent Indigenous leaders and activists. Today, representatives of RAIPON openly engage in propaganda at international forums (primarily at the UN and the Arctic Council). They talk about all the blessings and the paradise that the Russian state has built for the Indigenous peoples of the North. They write denunciations against independent Indigenous leaders. And after the start of the war in Ukraine, which has been supported by RAIPON, its leaders became war criminals, since they are members of the Russian parliament with whose consent this war was started.

3.

I am very pleased that the authors of this volume and series are sharing their thoughts, stories and memories of arctic collaboration, as well as their ideas about the future. For my part, I would like to express several points regarding the future of possible Arctic cooperation with Russia.

Firstly, I consider it very important that scholars who are engaged in arctic research that involves Indigenous people raise and discuss the issue of colonization of Siberia and the fate of its Indigenous residents. This is not just a question of restoring historical justice. It is an issue of eradicating the lies on which the Putin regime is based, such as Russia following a special path or the Russian people being “God’s chosen ones”. It is the need to “cure”—at least, confront— the imperialism that is rooted in the population of Russia, and most notably among its ethnically Russian citizens.

Secondly, in communicating with many colleagues (government representatives, scientists, experts, Indigenous leaders), I see how nostalgic they are for past times. They expect and hope that the Putin regime will fall – and then everything will return to normal and be just fine. To me this is a profound delusion. Things won’t be the same as they used to be before! And the sooner the arctic community–political, academic, expert–realizes this, the sooner it will be possible to begin building a new system of relations with Russia, for effective interactions in the future.

The previous system of relations regarded Russia as a friendly country “with some of its own oddities and peculiarities.” We are all witnesses what this illusion led to after 24 February 2022.

What needs to be grasped? That “there is a dangerous enemy on the other side” and its “oddities and peculiarities” are not just whims of the regime, but the sources of its strength and danger to the outside world. Going forward, any policy and system of relations with Russia must be based on acknowledging this fact.

Thirdly, and perhaps paradoxically, based on what I said above, it is necessary to continue collaboration with those citizens of Russia who oppose the Putin regime and who wish to continue cooperation with the ‘West’. These persons may not be picketing or otherwise actively protesting the regime. In the current environment in Russia to do so would be a prison sentence. A key criterion for such persons is their refusal to participate in this bacchanalia of “Z-ing” [i.e., displaying the symbol ‘Z’ in multiple forms – eds.] and of “jingoistic frenzy.”

This is especially important for the Indigenous peoples of Russia and for their future. Supporting such persons and collaborating with them also generates an atmosphere of understanding in Indigenous communities of Siberia, where everyone knows practically everyone else. By doing so even in such inhuman conditions one can remain human.

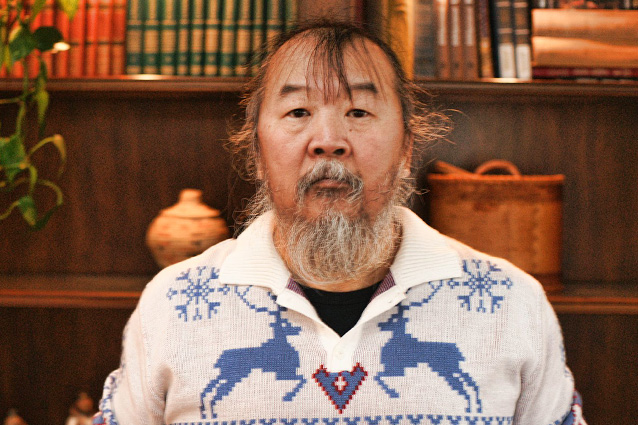

Pavel Sulyandziga, President of the International Indigenous Fund

for development and solidarity “Batani” (Batani Foundation),

Former first vice-president of the RAIPON (1997-2008),

Former member of the United Nations Permanent Forum

on Indigenous Issues (2005-2010), Former member of the United Nations Working Group

on Business and Human Rights (2011-2018)