Dmitry Berezhkov. Indigenous peoples is an integral part of the Arctic security

Today the Arctic security is threatened on all fronts, from extractive industries development and toxic contamination to the world’s fastest climate change. Recent political tensions between the West and Russia and the start of the war in Ukraine are putting Arctic security in a condition similar to the most hectic times that Arctic stakeholders experienced 40 years ago and earlier. And once again, as decades ago, the most vulnerable are becoming the most affected ones, including the Arctic indigenous communities.

In Russia, the Arctic is a home to multiple indigenous peoples. According to Russian official statistics, about one-third of the small-numbered indigenous peoples of the Russian North, Siberia, and the Far East live in the Arctic environment.

The Russian indigenous movement is a relatively young one. It emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union based on international law and the rapidly developing democratization of regional processes in 1990s Russia.

The Arctic has always been a focus of the Russian indigenous self-determination agenda. Following the wave of Gorbachyov’s democratization, the Russian Government agreed to include the newly established Russian indigenous peoples’ organization, RAIPON, as a Permanent Participant in the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy from the Russian side in 1991. As a result, the Arctic became the only region where Russia recognized indigenous peoples as valuable stakeholders of the international development agenda.

Further established Arctic Council became a unique interstates organization that recognized indigenous peoples as almost equals in decision-making. Unfortunately, it was the only Russian experience, as nowhere else Russia considered indigenous peoples as equal partners or even stakeholders in decision-making.

In general, negotiations with indigenous peoples within the Arctic Council have always been used by Russia as a presentational model for foreign officials and investors rather than as an actual pilot project for building partner relations with indigenous peoples.

But since the returning Vladimir Putin to the Kremlin in 2012 and especially after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the Russian Government tightened its control over the non-governmental sector and ethnic organizations, so today, RAIPON’s role has primarily been reduced to rubber-stamping government decisions.

After the war in Ukraine started in February 2022, the Western segment of the Arctic Council officially put the Arctic cooperation on hold. As a result, the Arctic Council and its unique model of interstate negotiations, with the involvement of the Indigenous organizations in decision-making, stepped into a zone of turbulence. Later it was announced the Council would ‘implement a limited number of projects that do not involve Russian participation. Meanwhile, Russia, who ironically holds the Council’s two-year rotating chairmanship, is doing it in complete solitude.

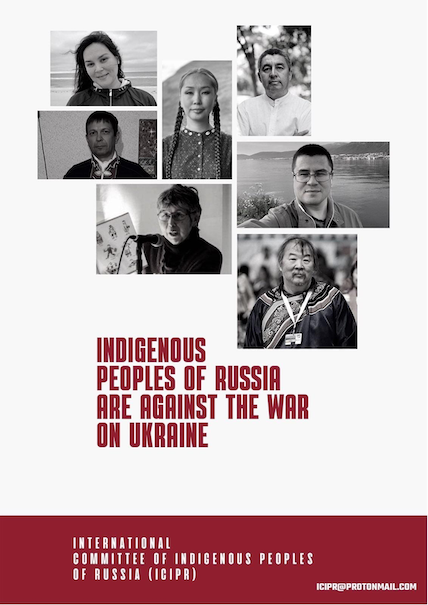

The Russian invasion influenced the country’s indigenous peoples on various fronts: through division of the indigenous movement, censorship, and silencing of indigenous representatives who opposed the war or even protecting their environmental rights, as Russian authorities now widely consider such actions as an antistate activity.

As the Russian-Ukranian conflict rages, the following questions are being raised: How will the conflict influence Russia’s and Arctic indigenous communities? How will it impact the states’ approach to indigenous peoples’ political development? How does it reflect on Arctic international relations and the Arctic Council, which has been perceived as one of the last major West-involved international platforms in which the Russian Federation remained a significant partner?

Notably, the seven Western states decided to boycott the Arctic Council without consultations with the Permanent Participants. For indigenous organizations, it signals a tectonic shift in regional governance and international legal practice and jeopardizes the hard-won slot of indigenous voices at the Arctic decision table.

Russia’s attack on Ukraine provoked a split among Arctic indigenous organizations themselves. The two-decade efforts to build up and strengthen relationships were torn down overnight. RAIPON openly aligned with the Government and supported Vladimir Putin’s actions in Ukraine. Saami Council suspended formal relations with Kola Sámi in the Murmansk region. At the moment, the Russian Government turned the Arctic Council’s indigenous agenda into a platform for aggressive propaganda under the RAIPON flag.

It is hard to tell precisely what Russia’s current indigenous policy is being aimed at. While seemingly aimed at the conservation of certain elements of indigenous cultures and symbolic markers of national identity like folklore, museums, languages and others, it takes the focus away from more substantive discussions regarding the reclamation of indigenous territories, livelihoods, natural resources, and self-government, and most importantly, from the discourse of rights per se. Instead, indigenous issues are handled in an increasingly paternalist manner.

Before February 2022 country’s strong paternalism was tempered by the presence of international actors in the region. Today, the Russian state is relentlessly nullifying any indigenous self-governance progress by tightening the state’s control over the lands and resources.

At the same time, we continue to believe that the region’s future cannot be discussed without Indigenous Peoples’ direct participation. Instead of fitting indigenous peoples into an existing system, states must change institutional arrangements and transfer control over indigenous lands and development agenda to indigenous institutions and actors. The legal framework must accommodate, advocate, and even take on indigenous forms instead of holding the implementation of Indigenous Peoples’ fundamental rights. The practice of indigenous rights must be in the control of indigenous people themselves.

Then, there is always a concern about how governing structures within indigenous groups truly reflect the interests and concerns of the indigenous communities. The internationally recognized implication is that the state must engage with self-organized indigenous representative bodies and with grassroots community members to avoid the cultivation of pro-government indigenous politicians and ensure the representation of the true indigenous interests. To magnify indigenous voices and support human rights in general, Arctic stakeholders, including states, must be ready to stand up as an ally with indigenous peoples organizations or their initiatives which governments do not control in one way or another.

What is known today is that the Arctic is heading into dark times. The region lost its status as a space immune from political tensions and matters of security and militarization. Arctic Council lost one member and is currently considering adapting its work to the new reality. The Russian Federation lost its place in the Arctic Council and its partner status in a number of strategic spheres. Permanent Participants are losing their collective voice and a hard-won seat at the table. Russian indigenous peoples lost a vital platform to address the international community, while RAIPON lost the legitimacy to represent the country’s indigenous voices.

We all have already heard Putin’s idea of creating a multiply diverse world that will be separated into “zones of responsibility,” like Germany was divided after the Second World war. And this is an attractive concept for many. At the same time, we need to remember that there are universal values and challenges like human rights, climate issues, our connected environment, which through their nature, are not dependent on the concrete political regime in the country.

We also heard some international voices which propose to return to the pre-Russian-Ukrainian-war model in the Arctic negotiations “to keep a channel of free-from-conflict negotiations with Russia”. This is natural when conflict sides, trying to avoid the “hot phase”, seek peaceful solutions. This is a natural form of compromising when military confrontation is at stake. At the same time, we cannot tolerate such compromises again at the expense of the most vulnerable stakeholders, including indigenous peoples.

Dmitry Berezhkov, member of the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (ICIPR), 10.03.2023