Russia’s War on Ukraine: Colonial Efforts on Two Fronts

Russia’s war in Ukraine is on its 211th day. As the number of fatalities wrought by Russia’s invasion escalates, Russian imperialism and colonial drive are further emphasized, both in Ukraine and Russia. The unlawful encroachment on the sovereign nation of Ukraine, acts of violence, and destabilization of the region are all efforts at new colonization. An overwhelming number of Russian soldiers killed in Ukraine come from Russia’s impoverished “ethnic republics”, which are also home to Indigenous Peoples, already devastated by economic instability, and beset by discriminatory official policies and social norms alike. The war has also put immense pressure on Russian civil society, making disagreement with Russia’s actions and anti-war sentiment and action chargeable, leading to a tremendous increase in censorship, criminal prosecutions, and enforcement of new restrictive laws.

The Russian State and local governments are increasingly reluctant to release information on the numbers of service people killed, much less on the ethnic identities of the deceased; nevertheless, independent news sites such as Vazhnie istorii (IStories) and MediaZona have conducted in-depth investigations into the numbers. Through analysis of thousands of publications, these studies reveal the number of fatalities to be significantly higher than the Russian government has put forth. Furthermore, one of MediaZona’s main conclusions was that “most of the dead soldiers are very young people from poor regions.” While “poor regions” does not necessarily denote areas where Indigenous communities live, Russian imperial politics have instituted, and continue to foster, poorer socioeconomic circumstances in areas where the majority of Russia’s Indigenous Peoples reside.

Military censorship has made it incredibly difficult to find reliable data and to form an accurate understanding of the numbers and demographics of Russian military personnel killed in Ukraine. The exact count of Russian soldiers killed is not known and estimates vary widely. The Russian Ministry of Defense has only released official data on losses twice: March 2 (498 dead) and March 25 (1,351). The General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine reports Russia’s military death toll is around 35,000. An analysis of publications from regional media and social networks conducted by MediaZona, in collaboration with the BBC and a team of volunteers, confirms 6,219 deaths as of September 23. IStories’ investigation, which is updated daily, has verified 6,083 names of the deceased. MediaZona and IStories both emphasize that these numbers solely reflect data their teams have been able to verify through open sources rather than actual losses. In early June, the military prosecutor’s office in the Kaliningrad region demanded that the Pskov-based media site 60.ru take down their lists of deceased soldiers. This started a mass removal of lists from other regional media outlets. The Kaliningrad court’s decision, which stated that this information divulges State secrets and weakens morality, has become a norm throughout regions of Russia though individual obituaries continue to be published by regional media and social media public networks. As a consequence of the war, Russia’s mortality rate of young people has increased by approximately 20%. IStories’ investigative reports show that citizens of Saint Petersburg and Moscow, where over 12% of Russia’s entire population live, are hardly present among the fatalities. In contrast, in less heavily populated regions of the country, the mortality rate of young men has simply skyrocketed.

The “ethnic republics” most impacted by this current situation include, but are not limited to, Dagestan, Buryatia, Chechnya, Bashkortostan, and Altai. The Republics of Dagestan and Buryatia rank first and second, respectively, among these regions. The number of deaths of people from Dagestan has increased by 130% during the war; in Buryatia, 110% (according to the Telegram channel “Demography fell”, in the first three months of the war, confirmed deaths of military personnel from Buryatia increased the mortality rate of Buryat men ages 18–45 by 70% and mortality rate of young men under 30 by 270%). In Buryatia, there is at least one funeral of a soldier daily. The disproportionate number of dead soldiers who come from these regions exemplifies contemporary Russian colonialism––ethnic republics are overwhelmingly economically depressed though often sites of lucrative, intensive extractive industries; unemployment is high, particularly in villages, making military enlistment one of the only ways for young men to earn money; and ubiquitous patriotic propaganda, alongside a history of conditioning and institutionalizing ethnic Russian primacy, instills incredibly complicated feelings of loyalty to nation(s).

In March 2022, military registration and enlistment offices began to actively recruit contractors for a “special operation” without specifics (the war in Ukraine is called the “special operation” in Russia). Most of these aggressive recruitments unfolded in Russia’s economically depressed regions. Although varying among regions, in Dagestan offered salaries for enlisting in the “special operation” began at 177,000 rubles ($2,800 USD) for the rank of private, and went up to 215,000 rubles ($3,401 USD) for the rank of ensign. These numbers are astronomical when considering that the average salary in Dagestan is slightly more than 32,000 rubles ($506 USD). In 2020, Buryatia ranked 81st with regard to quality of life out of 85 regions in Russia and a 2022 RIA Novosti (Russian state-owned news agency) study based on data from the Ministries of Health and Finance, the Central Bank, and other open data sources found that out of these same 85 regions, Buryatia was 69th in terms of the population percentage living below the poverty line (19.9%). The regions with highest population percentages living below the poverty line in 2022 were the Republics of Tuva, Ingushetia, and Altai––notably also “ethnic republics” with Indigenous populations.

In addition to financial incentives, military service is often seen as an important, respectable social elevator and an ideological civil position across Russia, and especially in these areas. For example, in Buryatia the city of Kyakhta is known as a “military city” where the 37th Independ Guards Motor Rifle Brigade is based, in which at least four thousand people serve, and where “almost every boy dreams of a military career”. While such military cities exist, it is often smaller villages that supply the army with people and, consequently, bear the greatest losses. Lack of employment opportunities are often felt throughout Russia’s ethnic republic, pushing general migration outflows to increase, but these strains are even more acute in villages. Inculcation of patriotism, which is a key part of recruitment for Russia’s war on Ukraine, is increasingly rooted in World War II. Monuments to the victories of the USSR during World War II (called the “Great Patriotic War” in Russia) are everywhere in Russia––from large cities to small villages like that of Selenduma (Selenginski district, Buryatia).

During World War II, 386 Selenduma residents went to the front where almost half died. In their honor, a victory monument was erected in the village with all the names of the deceased. Today, the village of Selenduma has a population of 2,700 and the head of the rural administration’s reports that twenty three residents left for Ukraine means that every twentieth man (aged 15–44) is gone. The village of Kani (Kulinskii region, Dagestan)––once an extensive community––is now populated by around thirty families. In Kani there is the quintessential monument to those who died in World War II. So far, twenty men from the village have left for the war.

As elsewhere in Russia, the war has split societies, including Indigenous communities. Attitudes about the war are complicated and vary across and within regions. Ethnic republics are generally split over their loyalty to Putin and Russia and stance on the war. On the one hand, public demonstrations of support for the Russian invasion are frequent, but they are, time and again, met with resistance. There are Indigenous people who support the war and believe it to be righteous, protecting not only Russia, but their own communities. On March 1, 2022 the Russian Association for Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) issued a statement and public letter in support of the invasion of Ukraine, thereby backing the killing of civilians, women, children, Indigenous Peoples, and soldiers living in Ukraine. There are also Indigenous people who openly condemn the war, in particular mothers whose children have been sent to war. On March 11, the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia––comprised of “representatives of Indigenous Peoples living outside of Russia against [their] will”––released a statement of solidarity with the people of Ukraine in which they condemned RAIPON’s open endorsement of the war.

These feelings reflect convoluted attitudes and identities throughout the country. Opposing the “special operation” is dangerous. Anti-war initiatives taken on by civil society are increasingly met with severe, suppressive measures by the State, therefore, even if individuals oppose the war, vocalizing anti-war sentiment can result in fines, detention, harassment, intimidation, other forms of violence, and the already prevalent practice in Russia––arrests and imprisonment.

Prior to the invasion of Ukraine, Russian authorities had actively started using propaganda to preemptively justify a “special military operation” in Donbas. In the beginning of the war, Russian schools were given instructions for how to teach lessons about the war on Ukraine and similar recommendations were given to some Russian universities. The Ministry of Education sent elementary schools materials on how to lead lessons on “Anti-Russian sanctions”, “Heroes of our time”, and how to mitigate “fake news.”

Independent news and media sites in Russia have been blocked, state-operated news cannot publish or broadcast information that discredits the Russian government and its actions, and access to other media sources have been greatly restricted. In mid-March, Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, was banned in Russia due to allegations of extremist activities. The ban resulted in the blocking of Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and a slew of other websites (social media, news, civil society, government domains). Thus, having applications for these banned networking services downloaded on one’s phone is a punishable offense. In March, “public dissemination of deliberately false information about the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation”, “public actions discrediting the use of the Armed Forces, including calls for unauthorized public events,” and “calls for sanctions against Russia” were codified under amendments to the Criminal Code, which has made speaking out against the war a criminally liable act with punishment ranging from fines of thousands of rubles to imprisonment. According to data gathered by OVD-Info, an independent human rights media project, there have been 16,334 detentions for taking anti-war positions or related to anti-war protests since February 24, 2022 (this includes “preventive” detentions authorities practice using face recognition software). At the end of June, OVD-Info knew of 2,457 administrative cases filed against individuals for “discrediting” the army of the Russian Federation. Not only is pro-war propaganda infused into all aspects of Russian life and imperial ideology and nationalism institutionalized, non-compliance with them is exceedingly risky.

Nevertheless, there are Russians who, despite the risks, openly oppose the war. For many ethnic groups, the war on Ukraine is immensely evocative of Russia’s imperial conquest of their own traditional territories and historical and contemporary Russification policies. Ruslan Gabbasov, head of the Bashkir National Political Center, says that lingucide and ethnocide has been occurring and “[t]oday, genocide has been added to this both towards the Ukrainian people and towards the peoples of Russia, whose representatives are sent to far for slaughter”. This is not the first time in recent history in which the Russian State, in an all-too-familiar colonial practice, has recruited and sent contractors from ethnic republics to fight in imperialist-driven wars. Alexandra Garmazhaprova, a Buryat journalist and president of the Free Buryatia Foundation, which seeks to expose and dismantle racism and xenophobia in Russia and demystify information about the war, wrote in 2015 about the participation of Buryat soldiers in the war in southeastern Ukraine.

Not only are Indigenous ethnic minorities disproportionately dying in the State’s wars, they’re also deliberately used as the faces of wars, which often functions to distance war from a broader ethnic Russian public. The “national question”, which in the Soviet context described the two distinct modes in which nationhood and nationality were institutionalized, today manifests as paradoxical and concurrent State-upheld images of multinationality and ethnic Russian primacy. This question has taken on additional meaning in the context of the war on Ukraine. Preexisting anti-war and decolonial movements in Russia and diasporic communities and nascent ones, such as the Free Buryatia Foundation, are coming together to create a more united and collaborative movement. Members of Indigenous ethnic groups, such as Gabbasov and Garmazhaprova, are part of a larger phenomenon of anti-war national movements in which people of non-Russian ethnicity in Russia are simultaneously realizing a new sense of collective identity and a need to further distance themselves from Kremlin objectives in the name of the “Russian world.”

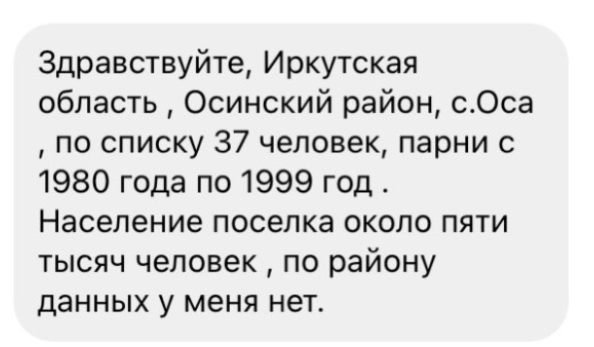

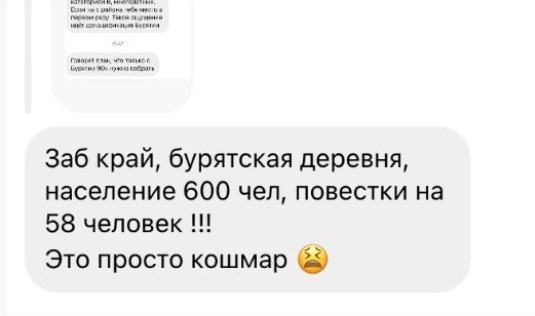

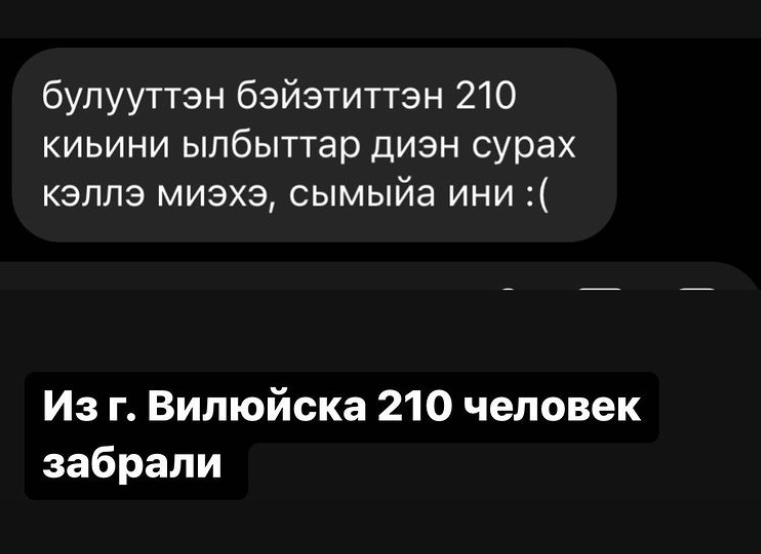

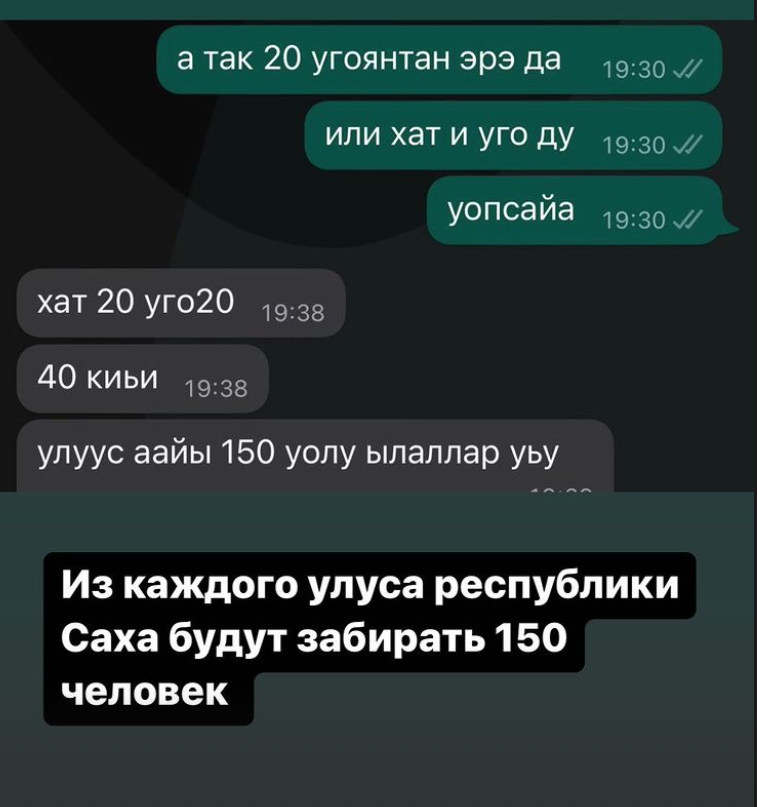

On Wednesday, September 21, 2022, following severe setbacks in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, President Putin announced an immediate “partial mobilization” of Russian citizens, which means citizens on reserve (men who have served their mandatory conscription terms or have deferred service) will be called up and those with past military experience will be conscripted. This is Russia’s first draft since the Second World War. Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu announced that Russia plans to call up 300,000 reservists. Since then, thousands of people have been arrested at anti-mobilization protests across the country, one-way tickets from Russia to Turkey and other countries that do not require entry visas for Russian citizens have sold out, and questions about who will escape the draft and who will be forced to fight become even more pressing. People in the “ethnic republics” already know what the probable answers to these questions are. The social media accounts of anti-war campaigns and organizations are brimming with information on how to potentially avoid the draft and anecdotal evidence submitted by individuals witnessing men receiving draft notices and being collected from their homes in the middle of the night and from universities and colleges. Military registration employees and enlistment officers are allowed to deliver summons to people’s places of residence and at their place of employment since, by law, employers are obligated to help military commissariats.

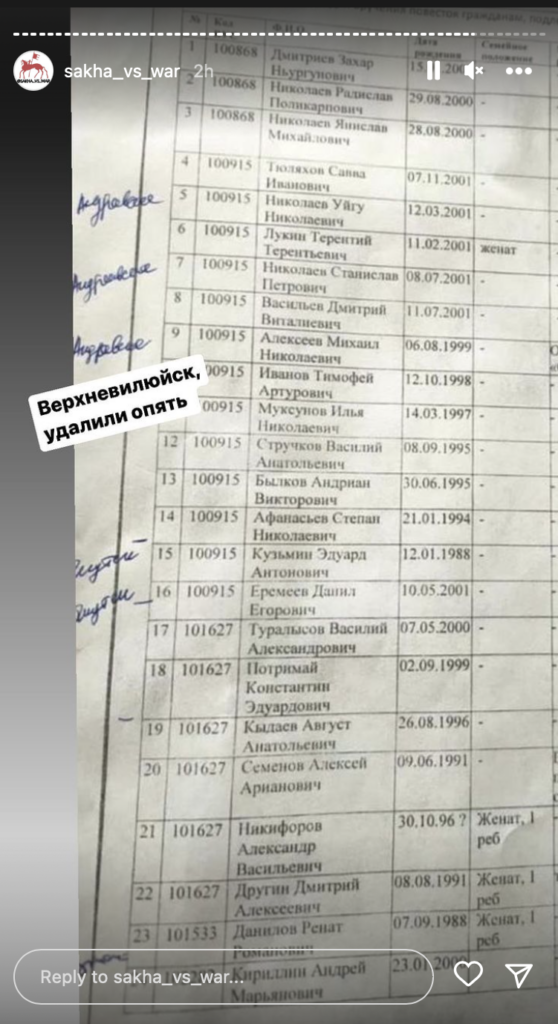

Additionally, lists of names of people who will potentially be drafted are circulating, with the hopes that the individuals listed can evade conscription.

Third column contains names, fourth column birth dates, fifth column contains information about spouse and children.

Though the exact numbers of draftees from “ethnic republics” is unknown, significant numbers are already being rounded up. Since much of the information about the “partial” mobilization is coming from various anonymous and nonsystematic sources and organizations do not have the time to thoroughly vet or process it, the Free Buryatia Foundation created a Google Form to help gather analytics, which are “more important now than ever [as] we need to understand how many people have been mobilized”. Video and anecdotal evidence from across Russia demonstrates large drafts taking place even in small villages and towns. Footage from the Sakha Republic appeared to show dozens of men being collected at the soccer stadium and loaded on buses headed to recruitment centers. These direct messages, photographs, videos, and documents suggest that the proposed summoning of 300,000 men will in fact be higher. Failure to appear at the military enlistment office after being subpoenaed results in a warning or administrative fine from 500 to 3 thousand rubles, according to Article 21.5 of the Administrative Code. However, new legislation hurriedly passed by the State Duma on Tuesday, September 20 sets new, harsher penalties for those who attempt to evade service, surrender, or refuse to fight. Individuals with wealth or connections might be spared from military service or potentially have the means to flee the country which underscores how men from largely impoverished regions are more likely to be fighting in the war.

Support for the war voiced by Indigenous-majority republican leadership, cultural organizations, and individuals is categorically and significantly ironic as it goes against the interest of the country as a whole, and of Indigenous Peoples specifically. Russia’s war on Ukraine is a colonial effort on two fronts, committing a double genocide as it continues its unlawful invasion and violent destablization of Ukraine while using Russia’s Indigenous Peoples as cannon fodder.