‘Keystone XL is dead!’

Dallas Goldtooth wrote on Twitter: “We took on a multi-billion dollar corporation and we won!!”

The Keystone XL pipeline project is officially terminated, the sponsor company announced Wednesday.

Calgary-based TC Energy is pulling the plug on the project after Canadian officials failed to persuade President Joe Biden to reverse his cancellation of its permit on the day he took office.

The company said it would work with government agencies “to ensure a safe termination of and exit from” the partially built line, which was to transport crude from the oil sand fields of western Canada to Steele City, Nebraska.

“Through the process, we developed meaningful Indigenous equity opportunities and a first-of-its-kind, industry leading plan to operate the pipeline with net-zero emissions throughout its lifecycle,” said François Poirier, TC Energy’s president and chief executive officer in a statement.

The pipeline has been front and center of the fight against climate change, especially in Indigenous communities. Native people have been speaking out, organizing, and in opposition of the project for several years.

“OMG! It’s official,” Dallas Goldtooth, Mdewakanton Dakota and Diné, wrote on Twitter regarding Keystone XL’s termination. “We took on a multi-billion dollar corporation and we won!!”

Goldtooth is part of the Indigenous Environmental Network. The network said it has been organizing for more than 10 years against the pipeline.

“We are dancing in our hearts because of this victory!” wrote the network in a statement. “From Dene territories in Northern Alberta to Indigenous lands along the Gulf of Mexico, we stood hand-in-hand to protect the next seven generations of life, the water and our communities from this dirty tar sands pipeline. And that struggle is vindicated. This is not the end – but merely the beginning of further victories.”

The network noted that water protector Oscar High Elk still faces charges for standing against Keystone.

Construction on the 1,200-mile pipeline began last year when former President Donald Trump revived the long-delayed project after it had stalled under the Obama administration.

It would have moved up to 830,000 barrels of crude daily, connecting in Nebraska to other pipelines that feed oil refineries on the U.S. Gulf Coast.

Biden canceled it in January over long standing concerns that burning oil sands crude would make climate change worse.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had objected to the move, although officials in Alberta, where the line originated, expressed disappointment in recent weeks that Trudeau didn’t push Biden harder to reinstate the pipeline’s permit.

Alberta invested more than $1 billion in the project last year, kick-starting construction that had stalled amid determined opposition to the line from environmentalists and Native American tribes along its route.

Alberta officials said Wednesday they reached an agreement with TC Energy, formerly known as TransCanada, to exit their partnership. The company and province plan to try to recoup the government’s investment, although neither offered any immediate details on how that would happen.

“We remain disappointed and frustrated with the circumstances surrounding the Keystone XL project, including the cancellation of the presidential permit for the pipeline’s border crossing,” Alberta Premier Jason Kenney said in a statement.

The province had hoped the pipeline would spur increased development in the oil sands and bring tens of billions of dollars in royalties over decades.

Climate change activists viewed the expansion of oil sands development as an environmental disaster that could speed up global warming as the fuel is burned. That turned Keystone into a flashpoint in the climate debate, and it became the focus of rallies and protests in Washington, D.C., and other cities.

Environmentalists who had fought the project since it was first announced in 2008 said its cancellation marks a “landmark moment” in the effort to curb the use of fossil fuels.

“Good riddance to Keystone XL,” said Jared Margolis with the Center for Biological Diversity, one of many environmental groups that sued to stop it.

On Montana’s Fort Belknap Reservation, tribal president Andy Werk Jr. described the end of Keystone as a relief to Native Americans who stood against it out of concerns a line break could foul the Missouri River or other waterways.

Attorneys general from 21 states had sued to overturn Biden’s cancellation of the pipeline, which would have created thousands of construction jobs. Republicans in Congress have made the cancellation a frequent talking point in their criticism of the administration, and even some moderate Senate Democrats including Montana’s Jon Tester and West Virginia’s Joe Manchin had urged Biden to reconsider.

Tester said in a statement Wednesday that he was disappointed in the project’s demise, but made no mention of Biden.

Wyoming Sen. John Barrasso, the top Republican on the Senate energy committee, was more direct: “President Biden killed the Keystone XL Pipeline and with it, thousands of good-paying American jobs.”

A White House spokesperson did not immediately respond to a request for comment on TC Energy’s announcement. In his Jan. 20 cancellation order, Biden said allowing the line to proceed “would not be consistent with my administration’s economic and climate imperatives.”

TC Energy said in canceling the pipeline that the company is focused on meeting “evolving energy demands” as the world transitions to different power sources. It said it has $7 billion in other projects under development.

Keystone XL’s price tag had ballooned as the project languished, increasing from $5.4 billion to $9 billion. Meanwhile, oil prices fell significantly — from more than $100 a barrel in 2008 to under $70 in recent months — slowing development of Canada’s oil sands and threatening to eat into any profits from moving the fuel to refineries.

A second TC Energy pipeline network, known simply as Keystone, has been delivering crude from Canada’s oil sands region since 2010. The company says on its website that Keystone has moved more than 3 billion barrels of crude from Alberta and an oil loading site in Cushing, Oklahoma.

Why Indigenous knowledge should be an essential part of how we govern the world’s oceans

Our moana (ocean) is in a state of unprecedented ecological crisis. Multiple, cumulative impacts include pollution, sedimentation, overfishing, drilling and climate change. All affect the health of both marine life and coastal communities.

To reverse the decline and avoid reaching tipping points, we must adopt more holistic and integrated governance and management approaches.

Indigenous peoples have cared for their land and seascapes for generations, using traditional knowledge and practices. But our research on marine justice shows Indigenous peoples face ongoing challenges as they seek to assert their sovereignty and authority in marine spaces.

We don’t need to wait for innovative Western science to take better care of the oceans. We have an opportunity to empower traditional and contemporary Indigenous forms of governance and management for the benefit of all people and the ecosystems we are part of.

Our research highlights alternative governance and management models to improve equity and justice for Indigenous peoples. These range from shared decision-making with governments (co-governance) to Indigenous peoples regaining control and re-enacting Indigenous forms of marine governance and management.

Indigenous environmental stewardship

Throughout Oceania, Indigenous marine governance is experiencing a revival. The long-term environmental stewardship of Indigenous peoples is documented around the globe.

In Fiji, customary marine tenure is institutionalised through the qoliqoli system. This defines customary fishing areas in which village chiefs are responsible for managing fishing rights and compliance.

Coastal communities in Vanuatu continue to create and implement temporary marine protection zones (known as tapu) to allow fisheries stock to recover. In Samoa, villages are able to establish and enforce local fisheries management.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, Māori environmental use and management is premised on the principle of kaitiakitanga (environmental guardianship) rather than unsustainable extraction of resources.

Australian Aboriginal societies likewise use the term “caring for country” to refer to their ongoing and active guardianship of the lands, seas, air, water, plants, animals, spirits and ancestors.

From the mountains to the sea

These governance and management systems are based on Indigenous knowledge that connects places and cultures and emphasises holistic approaches. The acknowledgement of inter-relationships between human and nonhuman beings (plants, animals, forests, rivers, oceans etc.) is a common thread. So is an emphasis on reciprocity and respect towards all beings.

Coastal and island Indigenous groups have specific obligations to care for and protect their marine environments and to use them sustainably. An inter-generational thread is part of these ethical duties. It takes into account the lessons and experiences of ancestors and considers the needs of future generations of people, plants, animals and other beings.

In contrast to Western ways of seeing the environment, the Australian Indigenous concept of country is not fragmented into different types of environment or scales of governance. Instead, land, air, water and the sea are all linked.

Likewise, for Māori, Ki uta ki tai (from the mountains to the sea) encapsulates a whole-of-landscape and seascape view.

Sharing knowledge across generations

Māori hold deep relationships with their rohe moana (saltwater territory). These are increasingly recognised by laws that emphasise Indigenous rights based on Te Tiriti o Waitangi. One example is the Integrated Kaipara Harbour Management Group, which co-manages the Kaipara Moana (harbour). The co-management agreement specifies shared responsibilities between different Māori entities (Kaipara Uri) and government agencies.

The agreement recognises Kaipara hapū (sub-tribes) and iwi (tribe) rights, interests and duties. It provides financial support to enable them to enact kaitiakitanga practices as they work to restore the mauri (life force) of the moana through practical efforts such as replanting native flora and reducing sedimentation.

They are using their mātauranga Māori (Māori Knowledge) alongside scientific knowledge to enact kaitiakitanga and ecosystem-based management.

Another co-management agreement is operating in Hawai’i between the community of Hā‘ena (USA) and the Hawai’ian state government. The Hā‘ena community operates an Indigenous fishing education programme. Members of all ages camp together by the coast and learn where, what and how to harvest and prepare marine products.

In this way, Indigenous knowledge, with its emphasis on sustainable practices and environmental ethics, is transmitted across generations.

Indigenous knowledge, values and relationships with our ocean can make significant contributions to marine governance. We can learn from Indigenous worldviews that emphasise connectivity between all things. There are many similarities between ecosystem-based and Indigenous knowledge management systems.

We need to do more to recognise and empower Indigenous knowledge and ways of governing marine spaces. This could include new laws, institutions and initiatives that allow Indigenous groups to exercise their self-determination rights and draw on different types of knowledge to help create and maintain sustainable seas.

Alaska Native corporation to protect its land, dealing blow to massive gold mine project

The nearly $20 million agreement includes land near Bristol Bay that covers part of the company’s proposed route for transporting ore

Growing up in a small village in southwest Alaska, Sarah Thiele had a childhood defined by sockeye salmon.

Her father caught the silvery-red fish in the summer by the net-full as a commercial fisherman while her mother would cure and cold-smoke hundreds of filets so Thiele and her eight siblings, plus the family’s team of sled dogs, could dine on sockeye year-round.

Now 66, Thiele is a board member of the Pedro Bay Corp., an Alaska Native group that owns land near Bristol Bay, the site of the most prolific sockeye fishery in the world. It is also the precise spot where the backers of the Pebble Mine hope to build a road to transport ore.

Late last month, Thiele and nearly 90 percent of the corporation’s shareholders voted to let the Conservation Fund, an environmental nonprofit organization, buy conservation easements on more than 44,000 acres and make the land off limits to future development — including the mining road.

“I feel like we are doing our mission of preserving our heritage and our pristine lands from any development,” she said. “That is totally our identity, the fish and our land.”

In exchange for the surface rights, the corporation would receive nearly $20 million, including $500,000 for education and cultural programs for those in the village.

The deal — which has not been previously reported — will make it difficult for backers of a massive open-pit gold and copper mine to carry out their project because the new protections cover a portion of a critical route the Pebble Limited Partnership plans to use to transport ore from the mine.

“I would say if it’s not the nail in the coffin, it’s just waiting for the last tap of the hammer,” Tim Troll, executive director of the Bristol Bay Heritage Land Trust, who helped negotiate the easement, said in a phone interview. Given the agreement, he added, “I just don’t see any way that they could do this.”

The mine was already in trouble. President Biden expressed opposition to the project during last year’s campaign and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers denied a permit for the mine in November. But the Pebble Limited Partnership is appealing the Corps’ decision and said in a statement that the conservation deal would not change its plans.

The fate of Bristol Bay, its multibillion-dollar commercial fishing and tourism industry and the Indigenous people who live there has been contested for more than a decade. Although many of Alaska’s elected officials have supported mining there, an unusual coalition of environmentalists, Republicans, commercial fishermen and Alaska Natives helped persuade the Trump administration to block the mine project last year.

For those with ties to the small village of Pedro Bay on the shore of Lake Iliamna, the state’s largest lake and a natural nursery for Bristol Bay’s spawning salmon, the threat that some future version of the mine could damage this precious salmon habitat remains a chilling possibility.

“The salmon sustained us for how many thousands of years,” said Thiele, vice chair of the Pedro Bay Corp.’s Board of Directors. “So you really have to be very conscious that you don’t disturb their habitat.”

The conservation groups said they have begun a fundraising effort to pay for the easement among organizations and individuals interested in preserving wild Alaska and the salmon population. They plan to reach out to Bristol Bay’s commercial fishing industry, which has been valued in recent years at more than $2 billion, as well as other environmental organizations.

Pedro Bay residents would retain ownership of their land and be allowed to access it for subsistence hunting and fishing as well as cultural practices and some forms of economic development, such as tourism, said Larry Selzer, president and chief executive of the Conservation Fund.

“Iliamna Lake is the largest wild sockeye salmon fishery in the world. It’s a magnificent resource, unprecedented value, both economically and culturally, in addition to the wildlife values,” Selzer said.

For the Conservation Fund, the “primary objective” of the agreement is to protect the critical salmon habitat, Selzer said, but a secondary benefit is “to eliminate the threat of the potential construction of an industrial transportation route as part of the proposed Pebble Mine project.”

Under the Obama administration, the Environmental Protection Agency took the unusual step of vetoing the prospect of a mine in 2014 on the grounds it could imperil the region’s sockeye salmon fishery. But the agency reversed course during the Trump administration, allowing the Pebble Limited Partnership to apply for a federal permit.

The company, a subsidiary of Canadian-owned Northern Dynasty Minerals, estimated its proposed 20-year operation would span more than 13 miles and require the construction of a 270-megawatt power plant, natural-gas pipeline, 82-mile double-lane road, elaborate storage facilities and the dredging of a port at Iliamna Bay. EPA concluded the project would result in the permanent loss of 2,292 acres of wetlands and more than 105 miles of streams.

But in September, the nonprofit Environmental Investigation Agency released secretly recorded conversations in which Northern Dynasty Minerals chief executive Ronald Thiessen and his associate spoke about seeking political favors from Republicans in Alaska and Washington. Both of Alaska’s senators, Republicans Lisa Murkowski and Dan Sullivan, subsequently questioned the idea of approving the mine, and the Corps then determined the plan did not meet the Clean Water Act’s requirements.

Asked to comment Monday, Pebble Limited Partnership spokesman Mike Heatwole said in an email: “Our focus remains on working with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers as its conducts its administrative appeal of the Pebble Project Record of Decision. This recent development hasn’t really changed that focus in any way.”

The Alaska Natives around Iliamna Lake have long relied on subsistence hunting and fishing, including for moose, seals, trout and salmon. There are also fishing lodges on the lake that attract anglers from around the world.

The path to protect the land along Iliamna Lake dates back nearly a decade, according to Troll, when genetic studies of the salmon in the lake by University of Washington researchers indicated the northeast corner of Iliamna — and the rivers that fed it — were the most productive breeding grounds for millions of salmon that eventually make their way out into Bristol Bay.

In 2017, the Bristol Bay Heritage Land Trust, with the help of the Conservation Fund, negotiated an easement covering islands in the middle of the lake, more than 12,000 acres also owned mostly by the Pedro Bay Corp. That deal helped pave the way for the most recent agreement to conserve three large parcels in the northeast portion of the lake where three rivers — Knutson Creek, Pile River and Iliamna River — feed into it.

The Iliamna Lake watershed is “the most important salmon fishery in the entire world,” Selzer said, “and so this project has extreme importance for the future of the salmon and the rest of the ecosystem.”

The fact that one of the proposed roads leading from the Pebble Mine project would pass through the Pedro Bay Corp.’s native-owned land near the shores of the lake only added to the urgency for those looking to protect this habitat in recent years.

Although it is unclear whether the new easement would block the company from constructing what it calls “the northern route,” Selzer said it would be “extremely difficult” and probably would deter future investors from financing the project. The company identified the route leading to Cook Inlet as its preferred route, and the Corps determined that it was the “Least Environmentally Damaging Practicable Alternative” for transporting minerals from the mine.

Matt McDaniel, the chief executive of the Pedro Bay Corp. and a spokesman for the community, said that for the corporation and the village of Pedro Bay, the proceeds from the conservation easement “immediately will impact and support these communities and we can send our kids to school and pass out dividends.”

Their decision to enter the agreement to preserve their land “was not specifically about Pebble,” he said. “It’s more about protecting the land from the effects of any type of development.”

Thiele — who now lives in Wasilla, but returns each summer to the village to fish — noted it is wedged in between the lake and the mountains, leaving little room for development.

“I’ve always been a little terrified about a big road going through,” she said. “We want people to be able to go there and experience it the way their mothers, their grandparents, their great-grandparents experienced it.”

‘I promised Brando I would not touch his Oscar’: the secret life of Sacheen Littlefeather

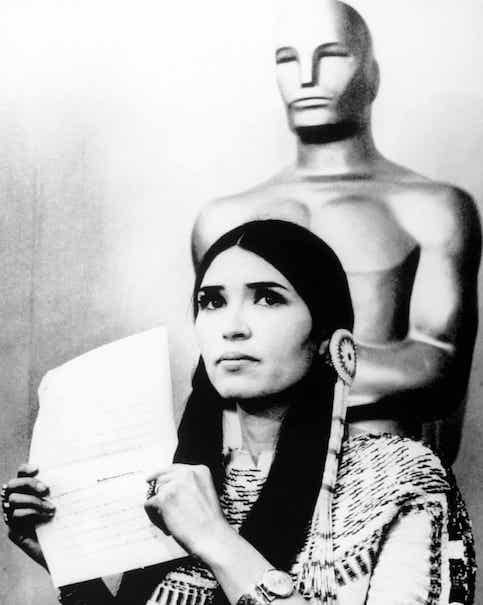

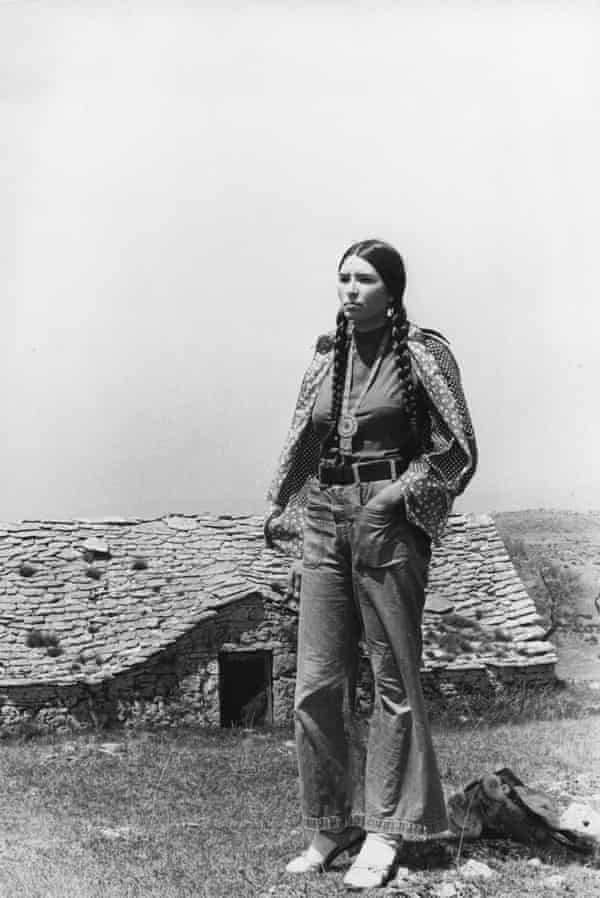

In 1973, she made history at the Academy Awards, appearing in place of Marlon Brando, declining his statuette and making a speech about Native American rights. She has been speaking out ever since

Sacheen Littlefeather begins by announcing that this will be one of her last interviews: “I’m very, very ill. I have metastasised breast cancer – terminal – to my right lung. And I’ve been on chemotherapy for quite some time, and daily antibiotics. As a result, my memory is not as good as it used to be … I’m very tired all the time because cancer is a full-time job: the CT scans, MRIs, laboratory blood work, medical visits, chemotherapy, infectious disease control doctors, etc, etc. If you’re lazy, you need not apply for cancer.”

For the next couple of hours, speaking over Zoom from her home in northern California, as she trips down memory lane her solemn demeanour gives way to chattiness and laughter. At 74, she has lived a full, eventful life, though she will be for ever remembered for an event that took up little more than one minute of it, on the night of 27 March 1973. This was when she took the stage at the 45th Academy Awards to speak on behalf of Marlon Brando, who had been awarded best actor for his performance in The Godfather. It is still a striking scene to watch. Amid the gaudy 70s evening wear, 26-year-old Littlefeather’s tasselled buckskin dress, moccasins, long, straight black hair and handsome face set in an expression of almost sorrowful composure, make a jarring contrast.

When the presenter, Roger Moore, attempts to hand Littlefeather Brando’s Oscar she holds out her hand as if to push it away. She explains that Brando cannot accept the award because of “the treatment of American Indians today by the film industry”. The crowd interrupts her, half-applauding, half-booing. “Excuse me,” she says calmly, then continues: “And on television and movie reruns, and also with recent happenings at Wounded Knee.” At the time, Wounded Knee, in South Dakota, was the site of a month-long standoff between Native American activists and US authorities, sparked by the murder of a Lakota man. Littlefeather ends her speech begging that “in the future, our hearts and our understandings will meet with love and generosity”.

At the time, nobody knew what to make of it. Not the audience, the press or the 85 million people watching on television (this was the first year the Oscars were broadcast internationally via satellite). Was it a prank? A surrealist performance piece? Littlefeather was rumoured to be a hired actor, a Mexican impostor, a stripper. “It was not a performance, it was a real presentation,” she says. “I think that’s what took people by surprise: that it was so real. It really touches people’s hearts to this day.”

It was hastily planned, says Littlefeather. Half an hour before her speech, she had been at Brando’s house on Mulholland Drive waiting for him to finish typing an eight-page speech. She arrived at the ceremony with Brando’s assistant, just minutes before best actor was announced. Howard Koch, the producer of the Academy Awards show, immediately informed her she could not read it – and she would be removed from the stage after 60 seconds. “And then it all happened so fast when it was announced that he had won. I had promised Marlon that I would not touch that statue if he won. And I had promised Koch that I would not go over 60 seconds. So there were two promises I had to keep.” As a result, she improvised her speech.

However valid Brando’s charge of the way Hollywood stereotyped Native Americans, it did not go down well that night. John Wayne, serial slaughterer of Native Americans on-screen and self-professed white supremacist off it, just happened to be in the wings during Littlefeather’s speech. “During my presentation, he was coming towards me to forcibly take me off the stage, and he had to be restrained by six security men to prevent him from doing so.” Presenting best picture soon after (also for The Godfather), Clint Eastwood quipped: “I don’t know if I should present this award on behalf of all the cowboys shot in all the John Ford westerns over the years.” When Littlefeather got backstage, she says, there were people making stereotypical Native American war cries at her and miming chopping with a tomahawk. After talking to the press, she went straight back to Brando’s house where they sat together and watched the reactions to the event on television.

But Littlefeather is proud of the trail she blazed. She was the first woman of colour, and the first indigenous woman, to use the Academy Awards platform to make a political statement. Today they are almost expected, but in 1973 it was radical. “I didn’t use my fist [she clenches her fist]. I didn’t use swearwords. I didn’t raise my voice. But I prayed that my ancestors would help me. I went up there like a warrior woman. I went up there with the grace and the beauty and the courage and the humility of my people. I spoke from my heart.”

Littlefeather’s life up to that point had been difficult. Her father was Native American, a mix of Apache and Yaqui, and her mother was white. They met in Arizona – where mixed-race couples were still illegal – so moved to Salinas, California, working as saddle-makers and leather-stampers. “My biological parents were both mentally ill and unable to raise me,” she says. “I was a child who was abused and neglected. I was taken away from them at age three, suffering from tuberculosis of the lungs. I lived in an oxygen tent at the hospital, which kept me alive.” She was raised by her maternal grandparents, but saw her parents regularly. She recalls a time as a small child when she interrupted her father beating her mother – by hitting him with a broom. “I think that’s when I really became an activist.” Her father chased after her. “I escaped through a doorway and I ran with all my might down the road. And he got in the pickup truck, and he tried to run me over. There was a grove of trees. And it was near dark. I ran up a tree, and he couldn’t find me. I stayed up in the tree and I cried myself to sleep.”

Littlefeather was between two worlds. Since the late 19th century, there had been a concerted project in the US to “make Indian people white”, she explains, spearheaded by federal government and Christian schools for Native American children. “They wanted to make us something else. And this leads us into terrible pain, into suicide, into alcoholism, into jails.” She did not fit in at the white, Catholic school her grandparents sent her to. “There was a lot of racism. I was called the N-word.” When she was 12, she and her grandfather visited the historic Roman Catholic church Carmel Mission, where she was horrified to see the bones of a Native American person on display in the museum. “I said: ‘This is wrong. This is not an object; this is a human being.’ So I went to the priest and I told him God would never approve of this, and he called me heretic. I had no idea what that was.” In her teens, Littlefeather had a breakdown and was hospitalised for a year. She attempted suicide. “I was so confused about my own identity, and I was suffering,” she says. “I could not tell the difference between me and my pain.”

Fortunately, in the late 1960s and early 70s Native Americans were beginning to reclaim their identities and reassert their rights. After her father died, when she was 17, Littlefeather began visiting reservations in Arizona, New Mexico and California. She visited Alcatraz when it was occupied by Native American activists in the early 1970s. She travelled around the country, between camp-outs and pow-wows, learning traditions and dances, making outfits. “I really had a breakthrough, with other urban Indian people, getting back into our traditions, our heritage. The old people who came from different reservations taught us young people how to be Indian again. It was wonderful.”

By her early 20s Littlefeather was working as public service director at a San Francisco radio station, and head of the local affirmative action committee for Native Americans, studying representation in film, television and sports (they successfully campaigned for Stanford University to remove their offensive “Indian” sports team symbol). One of her neighbours was Francis Ford Coppola. “I used to hike the hills of San Francisco every day,” she says. “He’d be sitting on his porch, drinking iced tea.” She got to know him to say hello to. At the time, many celebrities were expressing interest in Native American affairs, including Jane Fonda, Anthony Quinn and Burt Lancaster. Sometimes it was sincere, at others more self-interested, she says. So, when she heard Marlon Brando speaking about Native American rights, “I wanted to know if he was for real”. She wrote a letter to him and, walking past Coppola’s house one day, said: “Hey! You directed Marlon Brando in The Godfather.” She asked him for Brando’s address. Eventually, Coppola gave it to her.

She heard nothing for months, but one night a man phoned her at the radio station. “He said: ‘I bet you don’t know who this is.’ And I said: ‘Sure I do.’ And he said: ‘Well, who is it?’ I said: ‘It’s Marlon Brando. It sure as hell took you long enough to call. You beat “Indian time” all to hell.’ And we started to laugh as if we’d known each other for ever.”

They talked for about an hour, she says, then called each other regularly. Before long he was inviting her to visit. She stayed with him several times. They became good friends, but were never lovers or romantically involved. “No, no, he was far too old for me. He was my mother’s age, for God’s sake! He was extremely intelligent, and always entertaining. He had a great sense of humour. He would put on tons of different voices. We used to have a great time, laughing till tears were coming out of our eyes.

The Brando household was a busy and often heated place – with children, ex-wives and girlfriends. Brando sent her and his girlfriend Jill Banner to go and see his latest movie, Last Tango in Paris – Bernardo Bertolucci’s controversially graphic erotic drama (which would earn Brando another Oscar nomination). Littlefeather was not shocked, she says. “I just thought that it was about a man who had a very difficult relationship with women. I thought about Marlon in his early days with his mother. It was as though his life was being played out in that film.” Brando, too, had had difficult parents: his father was disapproving and unloving; his mother an alcoholic. “When he was young, they didn’t have therapy. Maybe that was why he was such a great actor – because he worked it out in his acting. He was able to share those real emotions with an audience. And maybe that was the love-hate relationship that he had with acting.”

Littlefeather’s Oscar speech drew international attention to Wounded Knee, where the US authorities had essentially imposed a media blackout. It was a key moment in the struggle for Native American rights and may well have saved lives, she suggests. It did little for her own career, however. She had had a few small roles in movies, including Freebie and the Bean and The Trial of Billy Jack. After the Oscars, she believes she was blacklisted by Hollywood. “I couldn’t get a job to save my life. I knew that J Edgar Hoover had gone around and told people in the industry not to hire me, because he would shut their talkshow or their production down. I got the word from people in the industry that that would happen to them.” She is not sure it helped Brando’s career, either. “I was a hotbed of controversy. And for any actor, I don’t know how safe that is for them, box office-wise.” They stayed in contact for a little while, but their lives naturally went separate ways. “We had our time together. We made history together.”

A few years later, when she was 29, Littlefeather’s lungs collapsed – a consequence of her childhood tuberculosis – and she became very ill. She found taking a holistic approach to her health helped and did a degree in holistic health and nutrition. She became a health consultant to Native American communities across the country, combining her knowledge with traditional medicine. She also reconnected with the Catholic faith, working with Mother Teresa caring for Aids patients in hospices, and led the San Francisco Kateri Circle, a Catholic group named after Kateri Tekakwitha, the first Native American saint. Their religious practice is a synthesis of both traditions, she explains. “For example, we have our buffalo dances in the middle of the mass.” It has helped her resolve her identity. “This is how I saved my life, by blending the two together. The acceptance of my dominant culture’s ways and my Indian ways together, living peacefully side by side.”

Now she is one of the elders transmitting knowledge down generations. Littlefeather gestures behind her to the sofa, where she mentors young Native American people. This is the real fulfilment in her life, she says. “When I go to the spirit world, I’m going to take all these stories with me. But hopefully I can share some of these things while I’m here.” Littlefeather talks about the end of life with the same composure and dignity she exhibited that night in 1973. “I’m going to another place,” she says. “I’m going to the world of my ancestors. I’m saying goodbye to you … I’ve earned the right to be my true self.”

Canada calls on pope to apologize after Indigenous children’s remains found

Government urges apology for role Catholic church played in residential school system after remains of 215 children discovered

Canada’s government has called on Pope Francis to issue a formal apology for the role the Catholic church played in Canada’s residential school system, days after the remains of 215 children were located at what was once the country’s largest such school.

Justin Trudeau’s government also pledged again to support efforts to find more unmarked graves at the former residential schools which held Indigenous children taken from families across the nation.

Chief Rosanne Casimir of the Tk’emlups te Secwepemc First Nation in British Columbia has said the remains of 215 children were confirmed last month at the school in Kamloops, British Columbia, with the help of ground-penetrating radar. So far none has been excavated.

The Kamloops Indian Residential school was Canada’s largest such facility and was operated by the Roman Catholic church between 1890 and 1969 before the federal government took it over as a day school until 1978, when it was closed. Nearly three-quarters of the 130 schools were run by Catholic missionary congregations.

A papal apology was one of the 94 recommendations made by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was set up as part of a government apology and settlement over the schools, and the prime minister asked the pope to consider such a gesture during a visit to the Vatican in 2017.

The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops announced in 2018 that the pope could not personally apologize for residential schools, even though he has not shied away from recognizing injustices faced by Indigenous people around the world.

“I think it is shameful that it hasn’t been done to date,” Marc Miller, Indigenous services minister, said.

“There is a responsibility that lies squarely on the shoulders” on the Catholic bishops of Canada, he added.

Carolyn Bennett, Indigenous relations minister, added that an apology by the pope would help those who suffered heal.

“They want to hear the pope apologize,” she said.

From the 19th century until the 1970s, more than 150,000 First Nations children were required to attend state-funded Christian schools as part of a program to assimilate them into Canadian society. They were forced to convert to Christianity and not allowed to speak their native languages. Many were beaten and verbally abused, and up to 6,000 are said to have died.

The Canadian government apologized in parliament in 2008 and admitted that physical and sexual abuse in the schools was rampant. Many students recalled being beaten for speaking their languages. They also lost touch with their parents and customs.

The prime minister, Justin Trudeau, has said the government will help preserve grave sites and search for potential unmarked burial grounds at other former residential schools. But Trudeau and his ministers have stressed need for Indigenous communities to decide for themselves how they want to proceed.

“We will be there to support every community that wants to do this work,” Bennett said. “We know right now that that work is urgent.”

The government previously announced C$27m (US$22m) for the effort. Bennett called that a first step.

“I know people are eager for answers but we do have to respect the privacy and mourning period of those communities that are collecting their thoughts and putting together protocols on how to honor these children,” Miller said.

Indigenous leaders plan to bring in forensics experts to identify and repatriate the remains of the children found buried on the Kamloops site. Perry Bellegarde, chief of the Assembly of First Nations, spoke with Trudeau this week and urged him to work with First Nations “to find all the unmarked graves of our stolen children”.

Murray Sinclair, the former chair of the reconciliation commission, said more sites will be found.

“We know there are lots of sites similar to Kamloops that are going to come to light in the future. We need to begin to prepare ourselves for that,” Sinclair said.

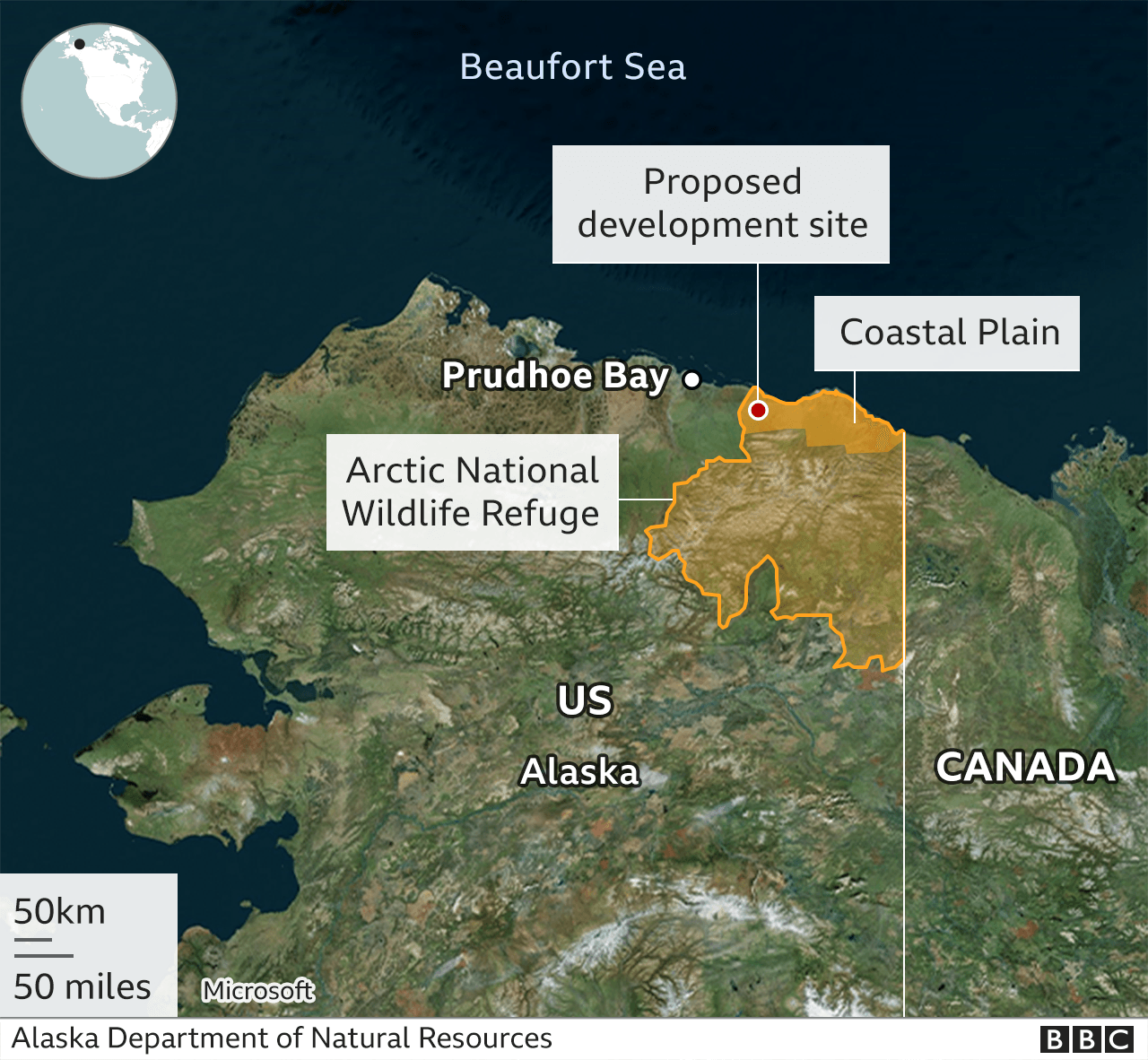

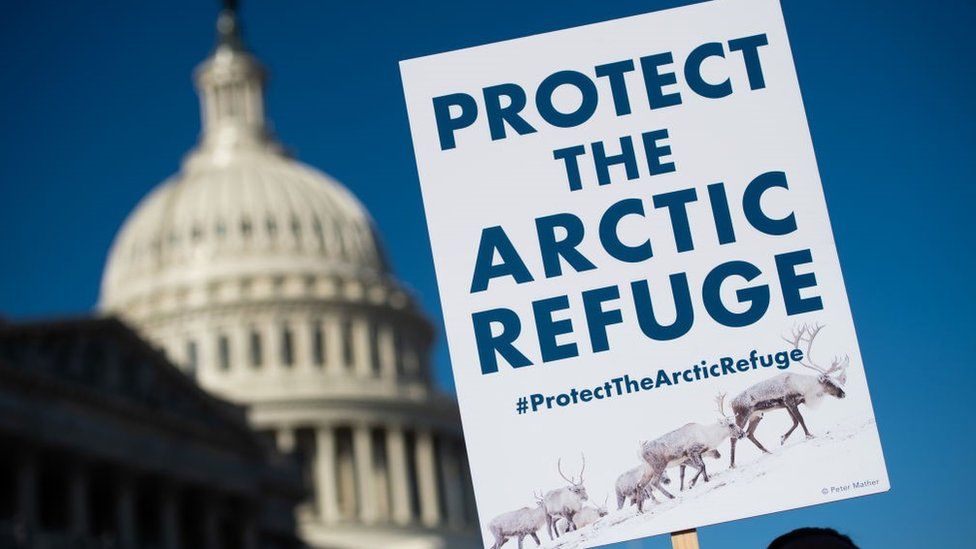

Alaska: Biden to suspend Trump Arctic drilling leases

US President Joe Biden’s administration will suspend oil and gas leases in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge pending an environmental review.

The move reverses former President Donald Trump’s decision to sell oil leases in the refuge to expand fossil fuel and mineral development.

The giant Alaskan wilderness is home to many important species, including polar bears, caribou and wolves.

Arctic tribal leaders have welcomed the move but Republicans are opposed.

- Why 2021 could be turning point for tackling climate change

- The wildlife at risk from drilling plan in Arctic refuge

- Trump opens wilderness up for oil drilling

Covering some 19 million acres (78,000 sq km), the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) is often described as America’s last great wilderness.

How did we get here?

The push for exploration in the park has been the subject of a decades-long dispute.

The oil-rich region is a critically important location for many species and is considered sacred by the indigenous Gwich’in people.

One side argues that drilling for oil could bring in significant amounts of money and provide jobs for people in Alaska, while the other has raised concerns over environmental and climate threats.

Days before his presidential term ended in January, Mr Trump went ahead with the first sale of oil leases in the region’s coastal plain as part of his push to develop more domestic fossil fuel production.

But the sale received little interest from the oil and gas industry. Companies said they were focusing their spending on renewable energy, amid a huge slump in oil prices. Several large US banks said they would not fund exploration in the area.

In total, 11 tracts were auctioned off, covering just over 550,000 acres, according to the Washington Post newspaper. The sale raised less than $15m (£11m) – far less than the government had hoped.

Most went to the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority, a state agency.

While estimates suggest around 11 billion barrels of oil lie under the refuge, it has no roads or other infrastructure, making it a very expensive place to drill.

During his campaign Mr Biden pledged to protect the habitat. Once in office, he directed the Interior Department to review the leases.

In a statement on Tuesday, the department said it had “identified defects in the underlying record of decision supporting the leases, including the lack of analysis of a reasonable range of alternatives”, required under environmental law.

White House National Climate Advisor Gina McCarthy said Mr Biden “believes America’s national treasures are cultural and economic cornerstones of our country”.

“He is grateful for the prompt action by the Department of the Interior to suspend all leasing pending a review of decisions made in the last administration’s final days that could have changed the character of this special place forever,” she added.

Since taking office, Mr Biden has signed executive orders aimed at freezing new oil and gas leases on public land, and has pledged to drastically cut carbon emissions.

But his administration disappointed environmental groups last week when the Justice Department defended a Trump-era decision to approve a major oil project on Alaska’s North Slope in the former Naval Petroleum Reserve.

How have people reacted to the suspension?

Arctic tribal leaders praised the decision.

“I want to thank President Biden and the Interior Department for recognising the wrongs committed against our people by the last Administration, and for putting us on the right path forward,” Tonya Garnett, special projects coordinator for the Native Village of Venetie Tribal Government, said in a statement.

“This goes to show that, no matter the odds, the voices of our Tribes matter.”

Kristen Miller, acting executive director of the Alaska Wilderness League, said suspending the leases was “a step in the right direction”.

But the Biden administration’s move was criticised in a joint statement by Republican senators Dan Sullivan and Lisa Murkowski along with representative Don Young and Governor Mike Dunleavy.

“This action serves no purpose other than to obstruct Alaska’s economy and put our energy security at risk,” said Ms Murkowski, who has represented Alaska in the Senate since 2002.

Mr Dunleavy added that the leases sold by the Trump administration “are valid and cannot be taken away by the federal government”.

Oil revenues are critical for Alaska, with every resident getting a cheque for around $1,600 every year from the state’s permanent fund.

Mr Dunleavy has previously said that opening the refuge for “responsible resource development” could “put more oil in our pipeline, put Alaskans to work, bring billions of dollars of investment to our state, support American energy independence, and provide critical revenues to our state and local communities”.

The Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority said it was disappointed by the decision, and had no reason to believe that the environmental analysis was inadequate.

A year after Arctic fuel spill, Norilsk Nickel continues to ignore Indigenous critics

On May 29, 2020, more than 21,000 tons of diesel fuel were spilled by metals giant Norilsk Nickel into the tundra of northern Russia’s Taimyr Peninsula, saturating the land and local waterways in oil. The incident is considered Russia’s worst oil spill in decades. Since then, Norilsk Nickel has made many rosy assurances, specifically towards Taimyr’s Indigenous tribes, who have dealt with pollution caused by the company for many years. Aside from paying the affected communities a small sum of money, Nornickel has done little else except pledge to change its conduct and policies – an empty promise it has made many times before.

Norilsk Nickel’s approach to Indigenous peoples in the region is paternalistic and colonial. It claims to observe international norms, especially as they pertain to Indigenous rights, yet it consistently fails to translate these declarations into action. While the company has a working relationship with Indigenous peoples in the Taimyr region, it is by no means an equal partnership, but rather a relationship between big business and colonized peoples. While Nornickel has allocated money towards projects for the Indigenous communities in Taimyr in the past, they have not shown respect for Indigenous self-determination. Norilsk Nickel has never considered that it operates on Indigenous land, and that maintaining an equitable relationship with the Indigenous peoples of the region is not a favor on the part of the company, but rather its obligation.

The company has an Indigenous rights policy, yet it does not mention Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), a right mandated by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples which is an international standard. While the company listed some of the support it has given to Indigenous peoples in Taimyr thus far, none of Norilsk Nickel’s press releases on the topic of cooperation with Indigenous peoples include a discussion of FPIC, or whether it plans to consult Indigenous peoples going forward.

Although Norilsk Nickel has pledged to spend 2 billion rubles on Indigenous programs over the next five years, which sounds like a respectable sum, less than 10 percent, or approximately 250,000 rubles per person (about USD 3000), of this funding will go directly to affected communities, while the majority will be spent on company-directed programming, anonymous sources say.

Furthermore, Norilsk Nickel’s contract for disbursing the funds stipulates that the conditions for receiving them is that communities will refuse to pursue further claims for funds and will not file claims in court to ask for more compensation in the future. Some community members now plan to legally challenge these conditions.

The company has also recently announced that it has signed agreements with multiple Indigenous organizations, and hired community members to serve as Indigenous spokespeople within the company, who say they represent all Indigenous peoples of Taimyr. The only people these representatives speak for is the company, since they are on Norilsk Nickel’s payroll and are entirely dependent on the company. Meanwhile, Nornickel refuses to lead a constructive dialogue with Indigenous peoples who raise criticisms about the company’s conduct. Norilsk Nickel says that it plans to carry out an expedition to consult Indigenous peoples of Taimyr about their “opinions,” that it is committed to ensuring transparency in all decisions, and that a council run by Nornickel will monitor the efficiency of financial allocation to communities.

Any educated person would be quick to point out that a company cannot be trusted to hold itself accountable impartially, and this is especially true in the case of Norilsk Nickel, which has fought repeatedly to block independent sources from inspecting its facilities or taking samples, even after the catastrophic oil spill last year. The company has also historically bribed environmental watchdogs to hide the extent of pollution in the region. A survey of the pollution that the company carried out following the spill found that “no major disaster happened” and that “ecosystems demonstrate a strong regenerative capacity,” which is an interesting conclusion considering that the extensive impact of the fuel spill and other pollution is well documented in news articles and scholarly papers. It is also well known that Arctic environments are particularly sensitive to pollution because the short growing season causes the landscape to regenerate slower. Given what we know about Norilsk Nickel’s conduct, it is therefore difficult to believe that future company initiatives or reports will objectively survey and analyze problems, especially when they concern Indigenous peoples.

Speaking on behalf of any Indigenous peoples is not the goal of this commentary. It is simply a demand that a real dialogue be carried out between Norilsk Nickel and the Indigenous peoples of Taimyr. Not with people paid by the company or the Russian government, but those who have suffered from the spill and the ongoing pollution of decades past, who have faced problems with access to food and their traditional lands due to environmental degradation. Conducting a dialogue with free people who know their rights and are not dependent on the company’s goodwill for their livelihoods is obviously much more difficult than working with people who are in a position of dependence and risk losing everything if they speak up against wrongdoing, but this is the proper way to conduct business, and if Norilsk Nickel wants to be taken seriously as an international company, this is the path they must take.

The goal is not to shutter Norilsk Nickel or its factories, but to make sure that the company observes the Indigenous rights that it claims to adhere to. If Norilsk Nickel does not observe these rights, then everyone must know that it is not following them, and that it cannot in good faith call itself a responsible company that upholds international standards. Norilsk Nickel must be held accountable, and the company must follow through on its promises – otherwise they will be seen as nothing but PR and propaganda.

Greetings,

The International Indigenous Fund for Development and Solidarity Batani, along with the support of the Society for Threatened Peoples (Switzerland), is holding a series of three online meetings dedicated to international experiences in indigenous rights protection and community development.

The first online meeting, which will be held in collaboration with the First Peoples Worldwide (USA), will take place on May 28, at 9:00 New York time (16:00 Moscow time), and will focus on International Judicial Mechanisms for Protecting the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Attorneys and scholars will discuss their experiences in working with the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. They will also discuss the European Court of Human Rights and its ability to protect the rights of indigenous peoples.

This online meeting will be attended by:

Kate R. Finn: Executive Director of First Peoples Worldwide. Her expertise concerns articulating how the impacts of development in Indigenous communities must be addressed at all levels of business and investment in order to build healthy Native economies and communities for generations. Prior to her directorship, Kate served as Staff Attorney for First Peoples.

Christina Stanton: Global Policy & Standard-Setting Manager at First Peoples Worldwide. She is responsible for integrating and elevating Indigenous rights into the international forum, including developing parallel strategy within the OAS to complement ongoing corporate and domestic efforts of Indigenous Peoples. She practiced in both tribal and state court and was engaged in policy work, contracting, employment, construction, landlord-tenant and federal Indian law.

Jan Mikael: PhD candidate at the Department of Law within the program of Durham University’s Arctic Research Centre for Training and Interdisciplinary Collaboration (DurhamARCTIC). Jan Mikael’s doctoral research examines the legal protection of property (possession) for indigenous peoples under the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms.

To attend, please fill out the registration form found with this link: https://forms.gle/ZuifqGyyqAKSXZhx9

Upon registration, you will have the opportunity to submit questions that you would like to be answered during the online meeting. A link to the meeting will be sent to all who register. Russian and English interpretation will be provided during the meeting.

Preliminary announcements about future events will be sent prior to each online meeting.

Stop Destruction of Life on Earth: CSOs urge banks to adopt “No Go” policy for biodiversity rich areas

Kherlen River in Mongolia (flowing to Dalainor Lake Ramsar wetland in China) is threatened by damming and water transfer to supply coal mining enterprises in Gobi Desert

Banks called upon to take action to protect biodiversity ahead of UN Biodiversity Conference in Kunming

Today, 24 organisations and civil society alliances based in 16 countries sent an open letter to 55 private sector banks globally, calling on them to take concrete action to help protect biodiversity and safeguard the rights of Indigenous and local communities.

The signatories seek commitments from banks to adopt a “No Go” policy for high biodiversity areas, introduce methodologies to measure the impactsof their investment and financing activities on biodiversity, strengthen biodiversity and human rights safeguards in sector finance policies, refrain from financing carbon and biodiversity offset projects and respect Indigenous rights and the role of human rights and environmental defenders.

The letter was sent to banks five months ahead of the UN Biodiversity Conference in Kunming, scheduled for October, which is tasked with reviewing the achievements of the Convention for Biological Diversity’s Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 and deciding on follow-up steps to halt the accelerating extinction rate of animal and plant species globally. While banks are not formal parties to the conference, civil society considers it crucial that banks commit to support the objectives and targets of the Convention on Biological Diversity.

The letter is part of the wider Banks and Biodiversity campaign, a civil society initiative launched in 2020 that seeks to safeguard the rights of Indigenous and traditional communities in formally, informally, or traditionally-held conserved areas, as well as to address the current crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, and emergence of zoonotic diseases. The main objective of the campaign is to see banks and other financial institutions adopt a “No Go” policy which prohibits direct or indirect financing of unsustainable, extractive, industrial, environmentally, and/or socially harmful activities in or impacting upon eight categories of protected areas. These “No Go” areas include, but are not limited to: Indigenous Peoples and Community Conserved Territories and Areas (ICCAs), areas recognized by international conventions and agreements, such as the Ramsar Convention and World Heritage Convention sites, and Iconic Ecosystems, such as the Amazon and the Arctic.

Marília Monteiro, Forests and Biodiversity Campaigner at BankTrack, commented: “Business activities such as infrastructure development, industrial agriculture, and the extractive fossil fuel and mining industries are major drivers of environmental degradation and biodiversity loss worldwide. As key financial supporters of these harmful activities, banks can have a major impact on either accelerating or slowing down these drivers of biodiversity destruction. The commitments we seek from banks will go a long way in ensuring safeguards against further biodiversity loss and violation of indigenous and traditional territories”.

Eugene Simonov, Coordinator of Rivers without Boundaries International Coalition (RwB) notes: “The importance of adopting “no go” policies is best exemplified by remaining free-flowing rivers – if you build a dam on such a yet unaffected river it will certainly interrupt key ecosystem processes and degrade habitat of endemic aquatic organisms. And there is no credible ‘mitigation’ solution for that other than to abstain from developing such infrastructure on new pristine watercourses. If we consider that 85% of known aquatic species populations are already in decline, a ‘No Go’ policy is an imperative to preserve biodiversity and protect local people who depend on those wild rivers”.

Paulina Garzón, of Latinoamérica Sustentable, added: “A ‘No Go’ policy is a long overdue obligation for financial institutions around the world. To have best practices and standards is not enough anymore. The ecological integrity of the world’s ecosystems is too close to collapse. We urge all banks to stop lending to destructive projects in precious habitats. It is time for the financial industry to respect our planet”.

Economic Policy Director of Friends of the Earth US Douglas Norlen added: “Biodiversity loss is an urgent global challenge on par with climate change, and yet banks have long failed to adequately recognize, let alone address the biodiversity impacts of their financing. The international banking sector must quickly rise to the challenge and prevent further biodiversity loss by adopting our proposed Banks and Biodiversity No Go policy in order to protect high biodiversity areas and respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Failing to stop biodiversity loss would be like failing to stop an open wound – a grim cascade of economic, social, and environmental collapse will most likely follow the bleed out.”

Marília Monteiro of BankTrack further added: “Currently, the majority of large international banks has not yet developed sufficient and effective systems to measure and monitor the impacts of their lending activities on biodiversity, and many have not yet publicly supported the objectives of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Many of the existing business initiatives aimed at biodiversity protection are based on the “financialization of nature” discourse, valuing biodiversity through a monetary lense while disregarding the intrinsic value of all nature, and not considering the underlying human and social issues. Indigenous peoples and local communities play a key role in protecting nature and biodiversity worldwide, and yet the banking sector as a whole is failing to guarantee the protection of their rights.”

In climate push, G7 agrees to stop international funding for coal

The world’s seven largest advanced economies agreed on Friday to stop international financing of coal projects that emit carbon by the end of this year, and phase out such support for all fossil fuels, to meet globally agreed climate change targets.

Stopping fossil fuel funding is seen as a major step the world can make to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial times, which scientists say would avoid the most devastating impacts of climate change.

Getting Japan on board to end international financing of coal projects in such a short timeframe means those countries, such as China, which still back coal are increasingly isolated and could face more pressure to stop.

In a communique, which Reuters saw and reported on earlier, the Group of Seven nations – the United States, Britain, Canada, France, Germany, Italy and Japan – plus the European Union said “international investments in unabated coal must stop now”.

“(We) commit to take concrete steps towards an absolute end to new direct government support for unabated international thermal coal power generation by the end of 2021, including through Official Development Assistance, export finance, investment, and financial and trade promotion support.”

Coal is considered unabated when it is burned for power or heat without using technology to capture the resulting emissions, a system not yet widely used in power generation.

Alok Sharma, president of the COP26 climate summit, has made halting international coal financing a “personal priority” to help end of the world’s reliance on the fossil fuel, calling for the UN summit in November to be the one “that consigns coal to history”.

He called on China to set out its “near-term policies that will then help to deliver the longer-term targets and the whole of the Chinese system needs to deliver on what President Xi Jinping has set out as his policy goals”.

BE MORE SPECIFIC, SAY GREEN GROUPS

The G7 nations also agreed to “work with other global partners to accelerate the deployment of zero emission vehicles”, “overwhelmingly” decarbonising the power sector in the 2030s and moving away from international fossil fuel financing, although no specific date was given for that goal.

They reiterated their commitment to the 2015 Paris Agreement aim to cap the rise in temperatures to as close as possible to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial times and to the developed country climate finance goal to mobilise US$100 billion annually by 2020 through to 2025.

U.S. climate envoy John Kerry urged countries in the Group of 20 world’s largest economies to match the measures.

But some green groups said while they welcomed the steps, the G7 needed to set a stricter timetable.

Rebecca Newsom, head of politics at Greenpeace UK, said: “Too many of these pledges remain vague when we need them to be specific and set out timetabled action.”

In a report earlier this week, the International Energy Agency (IEA) made its starkest warning yet, saying investors should not fund new oil, gas and coal supply projects if the world wants to reach net zero emissions by mid-century.

The number of countries which have pledged to reach net zero has grown, but even if their commitments are fully achieved, there will still be 22 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide worldwide in 2050 which would lead to temperature rise of around 2.1C by 2100, the IEA said in its “Net Zero by 2050” report.