If you don’t know treaties and sovereignty, you don’t know history

Sovereignty is sovereignty, treaties are treaties, and nation to nation is between and among sovereigns

There’s a widespread notion that “tribal sovereignty” and “Indian treaties” are legal, historical, practical and correct terms. Actually, sovereignty is sovereignty, and treaties are treaties, nation to nation is between and among sovereigns; the use of “tribal” or “Indian” or any modifier is both misleading and belittling.

A two-year research project, Reclaiming Native Truth,released its final report in May on a number of topics, including sovereignty, and found: “Sovereignty was poorly understood across all stakeholder groups in our study — from elected officials and policymakers to influencers from other fields to the general public. There was added confusion about the concept of more than 600 sovereign nations within the United States and about how tribes can be both sovereign nations and ‘reliant on the government.’”

Reclaiming Native Truth calls this misunderstanding “one of the most damaging, fueling many of the negative narratives and misperceptions, including the notion that Native Americans are receiving government benefits just for being Native.”

It is not generally understood that the treaties, sovereign agreements and treaty adjustment laws provide for the ongoing needed services and benefits for Native Nations. This is a small price for the United States to pay for having territory over which to govern and water and other riches to use. Native lands were shared and ceded in perpetuity, so payments, or services and programs, are to continue forever, as well.

Whenever a non-Native person makes the unfortunate statement that the benefits need to end (which happens at least once an hour in every time zone), a Native person responds, “Okay. Give us our land back.” If promises are broken and it’s the end of one side of a deal, it’s the end of the other side, too.

Thanks to the Reclaiming Native Truth project, there is data to show that most Americans know little to nothing about treaties between Native Nations and the United States, even though they are U.S. citizens’ treaties, too. Even more troubling, most do not know that or how the sovereignty of Native Nations and European Nations legitimized the sovereignty of the United States. Reclaiming Native Truth’s research and findings establish that this profound and widespread ignorance has far-reaching negative consequences in all areas of governance, economic development and health and well-being of our Native Peoples.

Reclaiming Native Truth’s research shows hope. For instance, it demonstrates that, when presented with a narrative that educates on the value of and values inherent in the treaties signed between the United States and Native Nations, support for laws that uphold tribal sovereignty increases by 16 percent. This may seem like a negligible margin. But, at a time when one percent of the national vote has meant the difference between one presidential candidate, who seemed indifferent to sovereign rights of Native Nations, and another, who seemed hostile and affirmed the Jacksonian campaigns to eradicate sovereign rights altogether, it becomes quite clear that Reclaiming Native Truth is on to something.

Benjamin Franklin inspired by the Six Nations’ confederacy

The following information is offered in that spirit of hope in the power of learning. And, begging the indulgence of the reader, kudos to those who can find some facts they never knew before.

It often is thought that sovereignty, land and rights were given or granted to Native Peoples by Europeans and Americans, even though no one brought any land with them when they came to our countries, and despite the fact that we enjoyed freedom, human rights and healthy lives long before their arrival.

Our governmental, jurisprudential and cultural systems were traditions of, by and for the people long before contact with non-Natives. While a united nations system was dreamt of in Europe, the first working models Europeans ever encountered were here, among myriad others, in the Council of Three Fires (Anishinaabe, Odawa, Potawatomi); the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Six Nations (Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Seneca, Tuscarora); the Lenape Clans and Nations; and the Muscogee (Creek) Confederacy of 60+ Nations and Towns.

Printer and publisher and U.S. Founding Father Benjamin Franklin was inspired by the Native confederations’ governance model and diplomacy, and printed the book, Indian Treaties, 1736-1762. After reading Archibald Kennedy’s 1751 pamphlet, The Importance of Gaining and Preserving the Friendship of the Indians to the British Interest Considered, Franklin wrote, “I am of the opinion that securing the Friendship of the Indians is of the greatest consequence for these Colonies.”

Franklin credited Canassatego, Onondaga, a leader of the Six Nations Iroquois, with advising the Thirteen Colonies – in a 1775 Council in Philadelphia — to confederate the Colonies in common defense and union, as the Haudenosaunee had done. It sometimes is said that American democracy also came from the Six Nations’ model; but, unlike Native democracy, the U.S., at first and for a long time, enfranchised only white male property-owners and did not allow half of its people to vote: the women.

Using his sardonic voice and employing a common prejudicial term, Franklin wrote: “It would be a very strange thing if Six Nations of Ignorant Savages should be capable of forming a Scheme for such an Union and be able to execute it in such a manner, as that it has subsisted Ages, and appears indissoluble, and yet a like union should be impracticable for ten or a dozen English colonies.”

Foreign kingdoms once believed and some still do that sovereignty is top-down, passed from deities to monarchs, with none for the people outside the royals, nobles and ministers of state. Native Nations and other representative democracies hold sovereignty as a collective inherent right, meaning national powers derive from the people as a whole and sovereignty emanates from within, not from any outside largess or force.

Sovereignty is the act thereof

As Haudenosaunee Faithkeeper Oren Lyons, Onondaga & Seneca, defines it, “Sovereignty is the act thereof.”

Native Nations respected each other’s sovereignty and made treaties for millennia before Europeans landed here and then made treaties with their countries. Many Native Nations made treaties with England, France, Netherlands, Spain and other foreign Nations before the existence of the United States.

Most pre-Revolutionary War treaties, between 1722 and 1774, were little more than temporary settlement of centuries-long feuds and wars among European powers, which they brought with them to this red quarter of Mother Earth. These treaties illustrate the tug-of-war tactics of European countries and the colonies to convince Native Nations to side with them or to maintain neutrality.

Euro-American treaties with Native Nations were requisite to acquiring territory and safe passage. Pre-Revolutionary War treaties were essential to establishing allies, trade and peaceful dealings. Post-war treaties were vital to gaining recognition of the sovereignty of the fledgling United States.

These goals were of such great importance that, in preparing for and to win the Revolutionary War in June of 1776, the Thirteen Colonies’ Continental Congress named three committees to draft the highest priority items. The Model Treaty was one of them. The other two were the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation.

Of the five Founding Fathers who wrote the treaties template, the principal author was John Adams of Massachusetts. He was a lawyer, farmer, diplomat, first U.S. vice president and second U.S. president. Another drafter was Benjamin Harrison V of Virginia. A state governor, speaker, and planation owner; he was the father and great-grandfather of two U.S. presidents, who championed treaty-making with Cherokee, Chickasaw, Muscogee and other Nations.

Three Pennsylvanians rounded out the treaty committee: John Dickenson, attorney and politician, who was a Delaware delegate to the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Benjamin Franklin, who was an author, diplomat, inventor, musician, editor, political theorist, postmaster, scientist and slave-owner-turned-abolitionist*.*Robert Morris, a free-trading financier with his own navy, who gave and secured major financing, ships and supplies for the Revolution; served as U.S. Agent of Marine and Superintendent of Finance; and co-designed the federal banking system with Alexander Hamilton of New York.

Both Adams and Franklin also were on the five-member committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence, with lead author, Founder Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, the first U.S. secretary of state and third U.S. president. Harrison chaired the Committee of the Whole, which oversaw the delegates’ editing and amending of the Declaration; and Dickenson chaired the 13-member committee on the Articles of Confederation.

The Model Treaty anticipated securing peace, friendship, trade and alliance with Nations, rather than with individuals, starting with those that had treaties with Great Britain or other European countries. The first Early Recognized Treaties was The Great Treaty of 1722, among the Provinces of New York, New Jersey and Territories and the Five Iroquois Nations, which the British note taker spelled Mohogs, Oneydes, Onondages, Cayuges & Sinnekees.

As soon as the Continental Congress adopted the Model Treaty on September 24, 1776, it returned to parties to the Pre-Revolutionary War Treaties to gain or lock in agreements and alliances, and to get Native Nations to side with or be neutral in the American Revolution. The earliest Treaties were efforts by the Continental Congress to agree to respect the sovereignty or at least recognize the existence of the United States. Franklin was dispatched to the Kingdom of France with the Model Treaty, and the U.S. made the Treaty with the Lenape, the Delaware Nation. The French and Lenape allies in the ongoing war were the first and second nations to make treaties with the U.S., in 1778, followed by the third in 1782 with the Dutch Republic, and the fourth in 1783 with Sweden.

After the 1783 Second Treaty of Paris ended the Revolutionary War, the U.S. sought and secured treaties with the nations of the Haudenosaunee, Lenape, Wyandot, Council of Three Fires (and, later, with Sauk), Kingdom of Prussia, Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Shawnee, Kingdom of Morocco, Muscogee (Creek), Plankeshaw, Kaskaskia, Miami, Eel River, Wea and Kickapoo. Additionally, the U.S. made a treaty with Seven Nations of Canada — Akwesasne Mohawk, Kahnawake Mohawk, Anishnaabeg (Algonquin and Nipissing), Oka, Odanak Abenaki, Becancour Abenaki, Jeune-Lorette Wyandot and Oswegatchie Onondaga.

Even after the War of Independence*,* nations around the world recognized the sovereignty of Native Nations, but did not know or understand the sovereignty of the United States. Sovereignty of and Treaties with Native Nations helped the United States establish itself as a viable diplomatic force and recognized country within the international community of nations. But, for some reason, most Americans do not know this.

U.S. relations with Native Nations were such a high priority that President George Washington met regularly with Native leaders, including providing a detailed explanation to the Seneca Nation that the first U.S. Indian law, the Nonintercourse Act of July 22, 1790, was “security for the remainder of your lands.” Acknowledging that “the six Nations have been led into some difficulties with respect to the sale of their lands since the peace,” he said that “these evils arose before the present government of the United States was established, when the separate States and individuals under their authority, undertook to treat with the Indian tribes respecting the sale of their lands.”

Washington drove home the point by saying that “the case is now entirely altered. The general Government only has the power, to treat with the Indian Nations, and any treaty formed and held without its authority will not be binding….No State nor person can purchase your lands, unless at some public treaty held under the authority of the United States. The general government will never consent to your being defrauded. But it will protect you in all your just rights.” Washington personally negotiated some treaties, most notably the 1790 Treaty of New York between the U.S. and Muscogee Nations, some of which was treated with the Muscogee delegates over dinner at his home in New York City, then the U.S. Capitol.

The U.S. Constitution makes clear that once a treaty is signed by the President and ratified by the Senate, it becomes the “supreme law of the land.” The U.S. has signed more than 500 treaties with Native Nations and has broken provisions of them all. There is a disconnect between the law enshrined in the U.S. Constitution and the law upheld in many U.S. courts and federal agencies.

What happened? Treaties were made between the U.S. and Native Nations that suited the goals of all parties — the U.S. was gaining territory over which to govern (which it certainly was not getting from the powerful colonies-turned-states) and Native Nations were gaining security that the general government would defend against encroachments and deprivations by the states, Americans and Europeans.

Powerful states, bad faith, and pandering

How did the U.S. go from an intellectual core of leaders who knew sovereignty, treaties, history and law to those who made anti-Indian pronouncements and genocidal policy because they did not know or did not care? Some U.S. leaders started pandering to the citizens’ and immigrants’ voracious appetite for personal property and wealth, especially after leaders of Georgia, New York and other powerful states started militating against the general government to get Indians out of “their” lands. Other U.S. leaders attempted to control the states’ excesses by returning Indian lands in treaties, and gaining Native agreement that certain lands were federal, not state territory.

In 1803, the U.S. purchased the immense Louisiana Territory from France, comprising lands that now include all of Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska and Oklahoma; most of the Mississippi River and Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota; much of Colorado, Louisiana, Montana, New Mexico, Texas and Wyoming; and some of the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Native Nations were not parties to the Louisiana Purchase, even though nearly all the territory involved Native land. This set off a flurry of treaty-making between the U.S. and Native Nations, resulting in both written and unwritten Treaties. At the same time, it lifted the pressure from the U.S. to immediately gain more land and challenge the existing states’ bad faith with Native Peoples.

Because many treaties were being broken by state action and federal inaction, some Native Nations sided with the British in the War of 1812, spawning a generation of Indian-fighters and states-righters, such as Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson of Tennessee, who captured Indian policy posts in Congress and then won the White House. Jackson fought the “Creek War” during the War of 1812; the Muscogee Confederacy split, with some fighting with the British, others with the U.S. and still others remaining neutral. Jackson did not discriminate and fought them all, using other Native Peoples to win the Battle of Horseshoe Bend of March 1814,and to cut off the noses for a count of the fallen Creek warriors.

Jackson was the U.S. military treaty commissioner who coerced the U.S.-Creek Treaty of Fort Jackson, Wetumpka Muscogee Territory, of August 1814, which purported to cede 23 million acres of Muscogee lands in present-day Alabama and Georgia. The 1814 Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812 between the U.S. and the United Kingdom, mandated the return of all lands to their pre-War boundaries. While boundaries were restored for all other Native lands in the north and south, only the Muscogee lands were not returned and the 1814 Jackson Treaty remained in place, in violation of the Treaty of Ghent.

Jackson had reason besides Indian-hating for disrespecting the Treaty of Ghent. It was signed December 24, 1814, ratified by the U.K. on December 30; then ratified and proclaimed by the U.S. on February 17 & 18, 1815. Jackson won the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815, after the Treaty of Ghent was signed by the parties and ratified by the U.K, and after other fighting ended. Jackson’s post-War battle catapulted him to national prominence and he took credit for ending the War that ended a month before his battle. He disclaimed any prior knowledge that the War was over, lest his military victory and hero status be delegitimized, and Congress awarded him a Congressional Gold Medalin February 1815: “For the defense of New Orleans.”

Jackson devoted much of his congressional and presidential tenure to undoing the pre- and post-War Native land boundaries and moving Native Peoples to the west of the Mississippi. In Congress, Jackson, his former aide de camp and other Indian-fighters developed the Indian removal scheme when they controlled the Indian Affairs Committees, and Jackson’s first presidential address to Congress of December 8, 1829, called for its enactment:

“Professing a desire to civilize and settle them, we have…thrust them farther into the wilderness….and the Indians….have retained their savage habits. A portion, however, of the Southern tribes, having mingled much with the whites and made some progress in the arts of civilized life, have lately attempted to erect an independent government within the limits of Georgia and Alabama (which) claiming to be the only sovereigns within their territories, extended their laws over the Indians, which induced the latter to call upon the (U.S.) for protection.”

Georgia and Alabama were a big part of Jackson’s base, and he made their case for removing Indians from “state” land. At the same time, he upheld his 1814 Fort Jackson Treaty dispossessing the Muscogee Nations and dismissed the Treaty of Ghent’s restoration of 1812 land boundaries, by not mentioning either one.

“Georgia became a member of the Confederacy…as a sovereign State….Alabama was admitted into the Union on the same footing with the original States….” Holding forth that his base states do not have “less power over the Indians within their borders than is possessed by Maine or New York,” his Message went on: “I informed the Indians inhabiting parts of Georgia and Alabama that their attempt to establish an independent government would not be countenanced by the Executive…and advised them to emigrate beyond the Mississippi or submit to the laws of those States.”

Blaming his predecessors, U.S policies and the Native Peoples for the situation, Jackson said: “Our ancestors found them the uncontrolled possessors of these vast regions. By persuasion and force they have been made to retire from river to river and from mountain to mountain, until some of the tribes have become extinct and others have left but remnants to preserve for a while their once terrible names. Surrounded by the whites with their arts of civilization, which by destroying the resources of the savage doom him to weakness and decay….

“It is too late to inquire whether it was just in the (U.S.) to include them and their territory within the bounds of new States, whose limits they could control. That step can not be retraced. A State can not be dismembered by Congress or restricted in the exercise of her constitutional power.”

Congress passed the Indian Removal Act a mere five months later, which is lightning speed for substantive law, and Jackson signed it on May 28, 1830. It applied to Native Peoples north and south, to friend and foe alike, resulting in the Potawatomi Trail of Death, the Cherokee Trail of Tears and the Navajo and countless other Long Walks. The Act required treaties, but the coercion and forced removals exposed as a sham its nod to sovereignty and treaties. The Muscogee Nations never signed a removal treaty, but were wrenched from their homelands and moved at bayonet point to Indian Territory (now, Oklahoma) anyway. The trauma of removal is so great and present in Muscogee and other citizens of removed Nations that many are Republicans today because Jackson was a Democrat.

Indian removal continued, but so did new treaties

Removals continued throughout the 1800s, but so did new treaties and agreements among sovereigns, illustrating that history is rife with contradictions and inconsistencies. In 1850-1851, U.S. and Native Nations made new treaties for passage through and limited outposts in the Great Plains and for land and fishing, gathering and hunting rights in the Pacific Northwest and Columbia River Basin. At the same time, California’s state leadership vehemently opposed treaties already concluded and sent to the Senate by the U.S. treaty commissioners. The Senate approved the other treaties but voted not to ratify those made with Native Peoples in California, leaving them without the promised security and protection of the U.S. and making them victims of bloodbaths by miners and gold rushers.

Removals and gold fever in Colorado, Oregon, South Dakota and elsewhere led directly to further attempted undermining of sovereignty and breaking of new and old treaties; and to the dehumanizing, destabilizing land-grabs, under the guise of fulfilling the treaty term, “arts of civilization.” Through congressional Civilization Funds, executive franchises were granted to Christian churches to proselytize to specific Indian Tribes for the entire century that started in 1800. The Civilization Regulations (1880s-1930s) criminalized all Native traditions, ceremonies, roaming away from the reservations and interfering with “progressive education” of the children, meaning: isolating them from their families, detribalizing and deculturalizing them, cutting their hair and washing their mouths and eyes with lye soap or beating them with boards and whips for not speaking English or failing to pray in a Christian way.

In the midst of all this civilization, the 1887 General Allotment Act and similar laws tried to “civilize” and “assimilate” Native Peoples and to abolish Native national ownership of land; parcels were allotted to individual Native persons and the “excess” lands were opened to land-rushing white settlers. In the nearly 50 years of Allotment until its end in 1934 by the Franklin Roosevelt Administration, two-thirds of Native Peoples’ lands were lost to taxes and banks, and from thefts and shady deals by railroad and utility owners and speculators in land, water, oil, timber, mining, stocks and crops.

Throughout the half-century of the rule of Civilization, federal bureaucrats issued directives to agents and soldiers in the field to “undertake a careful propaganda” against religious ceremonies and dances, which they did with great vigor. Ancestors and graves were robbed; sacred places were desecrated; and many holy mountains, waterfalls, shorelines, forests, deserts and canyons were renamed racial slurs and demonic references. People who participated in ceremonies – even those for mourning and burials — at those places or on reservations were demonized, arrested, starved, imprisoned or killed.

Propagandists told and retold their lies and newspapers sold and resold them until the general public thought the false narratives were true facts. President Theodore Roosevelt, like Jackson, was a propaganda machine for dealings with the Indians, whose population was down from many millions to the near extinction level of 250,000 and was called the Vanishing American.

In his First Annual Message in 1901, Roosevelt opined: “In my judgment…we should definitely make up our minds to recognize the Indian as an individual and not as a member of a tribe. The General Allotment Act is a mighty pulverizing engine to break up the tribal mass….We should now break up the tribal funds, doing for them what allotment does for the tribal lands….In the schools the education should be elementary and largely industrial. The need of higher education among the Indians is very, very limited.”

Three years later in 1904, Roosevelt allowed his Interior Secretary to reissue the Civilization Regulations. In 1906, he approved the Burke Act, authorizing federal assessments of Native persons as “competent and capable” before they could have fee simple patents to their own allotted land or become U.S. citizens. One month later, he signed the Antiquities Act, authorizing the President to declare as national monuments landmarks, places and objects of historic or scientific interest on federal land or under federal jurisdiction. This and other public domain laws took many more millions of acres of Native homelands and treaty territory, as well as sacred places that removals and federal forces prohibited and prevented Native Peoples from using and then declared them to be public lands because of they were not being used.

Lest any reader thinks that all this is in the distant past, please know that our current problems flow directly from this sorry history. And, in case anyone thinks that only U.S. leaders from a century ago think or talk like Andrew Jackson or Theodore Roosevelt, let’s move a little closer to now.

Many U.S. Presidents have said terminally dumb stuff that showed their ignorance of Native Peoples, and that would be okay if it didn’t translate directly into negative policies. President Ronald Reagan’s administrations in the 1980s tried to turn over Indian education to the states, give Indian trust monies to private banks to manage and to cut the federal Indian budget by one-third in each of the first six years (but, Congress pushed back and the schemes failed). While in the Soviet Union at Moscow State University in 1988, a student asked Reagan a question: “I’ve heard that a group of American Indians have come here because they couldn’t meet you in the United States….” After stumbling about whether they “had asked to see me,” he offered a polite “I’d be very happy to see them.”

Alas, the President went on: “Let me tell you just a little something about the American Indian in our land. We have provided millions of acres of land for what are called preservations—or reservations, I should say. They, from the beginning, announced that they wanted to maintain their way of life, as they had always lived there in the desert and the plains and so forth. And we set up these reservations so they could, and have a Bureau of Indian Affairs to help take care of them. At the same time, we provide education for them—schools on the reservations.

“And they’re free also to leave the reservations and be American citizens among the rest of us, and many do. Some still prefer, however, that way—that early way of life. And we’ve done everything we can to meet their demands as to how they want to live. Maybe we made a mistake. Maybe we should not have humored them in that wanting to stay in that kind of primitive lifestyle. Maybe we should have said, no, come join us; be citizens along with the rest of us.

“As I say, many have; many have been very successful. And I’m very pleased to meet with them, talk with them at any time and see what their grievances are or what they feel they might be. And you’d be surprised: Some of them became very wealthy because some of those reservations were overlaying great pools of oil, and you can get very rich pumping oil. And so, I don’t know what their complaint might be.”

It was a great teaching moment, but we couldn’t reach as many people as the President could. Reagan’s remarks furthered the stereotypes of us as “primitive,” oil-rich, ungrateful gripers, preserved in the past in places away from civilization. He also perpetuated the myth that the U.S. gifted us with a huge landmass, saying U.S. policies were a mistake and the U.S. was just humoring us. Whew.

President George W. Bush made news at a 2004 UNITY: Journalists of Color gathering in Washington, DC, when he answered a question posed by Mark Trahant, Shoshone-Bannock: “What do you think tribal sovereignty means in the 21st century and how do we resolve conflicts between tribes and the federal and state governments…?”

“Tribal sovereignty means that. It’s sovereign,” said the President. “You’re a … you’re a … you have been given sovereignty and you’re viewed as a sovereign entity.” His response drew considerable derision from the conferees, but he was not wrong, except with the word “given” – it cannot be said enough that sovereignty is not a gift.

President Bush was right in not repeating the modifier of “tribal” to sovereignty, which immediately makes our Nations’ sovereignty sound different from the sovereignty of United Nations countries — for example, Belize, Montenegro, Principality of Monaco, Republic of Ireland, Republic of Liberia, Republic of Seychelles, Socialist Republic of Vietnam, United Kingdom of Great Britain (England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales), United States or Vatican City State. Most Native Nations have larger land bases and populations than the smaller of these, and have greater longevity as nations than most, but the important thing the reader should take from this that sovereignty has no size, is not on a sliding scale – it either is or is not.

“And therefore,” Bush continued, “the relationship between the federal government and tribes is one between sovereign entities. Now, the federal government has got a responsibility on matters like education and security to help. And health care. And it’s a solemn duty. From this perspective, we must continue to uphold that duty….” Those are good and proper things for a president to say about an enormously complex topic, but I have no doubt that the laughter at his stammer still stings.

Attacks on sovereignty today

Today, attacks on laws — such as the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, Indian Child Welfare Act, Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act — are made possible by the fact that most Americans have no understanding of sovereignty or treaties. Indeed, many of the attacks launched against bedrock pillars of federal Indian law stem from false narratives that either erase our nationhood or dehumanize our people to the point that the sovereignty of our Nations cannot be considered.

I had the privilege of researching, curating and editing the Nation to Nation exhibition and book on treaties and sovereignty for the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian. Since launching Nation to Nation in 2014, we have been able to share brief histories of treaties and sovereignty to hundreds of thousands of lawyers, parents, teachers, doctors, veterans, taxi-drivers, federal employees, service workers, senators, artists, tourists and, perhaps most importantly, school children. The feedback has shown a hunger to learn and a commitment to keep and honor our promises.

But, Reclaiming Native Truth’s research shows that one exhibit simply is not enough. “On a broad level, most Americans seem to support Native peoples’ right to self-determination and find the constitutional guarantees of sovereign rights convincing. That said, many are confused about what sovereignty really means in the context of Native peoples and ask questions such as ‘Is it like a separate country, or is it like a state government?’”

We and our allies must find more and better ways to answer the questions and to address the national narrative that works against our sovereignty and humanity. Until we reclaim the narrative about our distinctiveness, our diversity, our sovereignty, our nationhood, our values and ourselves, we will continue to be caught in an erasure quagmire that was designed to secure our extinction.

We all must all do this work: moms, pops, students, activists, athletes, journalists, poets, educators, leaders, worker bees and public intellectuals. We must all work to reclaim and proclaim our true narrative of sovereignty and our treaties of peace, friendship and honor, forever.

Indigenous people are the world’s biggest conservationists, but they rarely get credit for it

More than 30 percent of the Earth is already conserved. Thank Indigenous people and local communities.

In a lush swath of tropical forest on the eastern coast of Mindanao, the second-largest island in the Philippines, you can glimpse the brilliant plumage of the rare rufous-lored kingfisher or — if you’re lucky — hear the shrill cry of the large Philippine eagle, a critically endangered species.

Wildlife is abundant here, but not because the region was left untouched in a protected area, or conserved by an international environmental organization. It’s because the territory known as Pangasananan has been occupied for centuries by the Manobo people, who have long relied on the land to cultivate crops, hunt and fish, and gather herbs. They use a number of techniques to conserve the land, from restricting access to sacred areas to designating wildlife sanctuaries and an offseason for hunting, owing in part to a traditional belief that nature and its resources are guarded by spirits.

Pangasananan is one of many areas around the world that remain ecologically intact due to the conservation practices of Indigenous peoples or local communities. Although these places are not widely documented by researchers, they cover an estimated 21 percent of all land on Earth, according to a new report by the ICCA Consortium, a group that advocates for Indigenous and community-led conservation.

That means Indigenous peoples and local communities conserve far more of the Earth than, say, national parks and forests. (Protected and conservation areas overseen by countries — some of which overlap with Indigenous territories — cover just 14 percent of all land on Earth, according to the report.) The consortium says its report is the first effort to try to measure the extent of areas conserved by Indigenous peoples and local communities, known as ICCAs or territories of life./cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22650150/photo15_billboard_icca.jpg) Leaders of the Manobo community made a sign at the entrance of a local ecotourism park surrounding a popular waterfall to inform visitors that it’s part of the Pangasananan territory. Courtesy of Glaiza Tabanao/ICCA Consortium

Leaders of the Manobo community made a sign at the entrance of a local ecotourism park surrounding a popular waterfall to inform visitors that it’s part of the Pangasananan territory. Courtesy of Glaiza Tabanao/ICCA Consortium/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22650151/photo20_community_meeting.jpg) A community meeting in the Pangasananan territory to discuss restoration and farming plans. Courtesy of Virgilio Domogoy/Matricoso

A community meeting in the Pangasananan territory to discuss restoration and farming plans. Courtesy of Virgilio Domogoy/Matricoso

Despite the outsize role that Indigenous peoples play in protecting nature, their contributions often go overlooked. The modern conservation movement was built on the false idea that nature starts out “pristine” and untouched by humans, as the environmental journalist Michelle Nijhuis has written. That put many of the movement’s early efforts, including protected areas, at odds with Indigenous land management — the very activities that created many landscapes that countries are now racing to protect.

“We’re discounted,” Reno Keoni Franklin, chairman emeritus of the Kashia Pomo Tribe in California, told Vox. “Tribal knowledge in land conservation is often used and quoted but rarely matters until a white person says it. Unfortunately, that’s just the truth of the last 100 years of land conservation in the US.”

The stakes couldn’t be higher today. More than 50 countries, including the US and the other wealthy nations that make up the G7, have committed to conserving at least 30 percent of their lands and waters by 2030. Some Indigenous activists fear that reaching that goal, known as 30 by 30, could come at the expense of Indigenous land rights.

But they also see an opportunity to change the paradigm of conservation to one in which the enormous contributions of Indigenous peoples are recognized and supported. The consortium’s report could help propel that shift. It finds that if you consider areas conserved by Indigenous and local communities, in addition to formally protected and conserved areas, more than 30 percent of the world’s land is already conserved.

Indigenous lands preserve biodiversity

A huge amount of land is owned or governed by either Indigenous peoples or local communities, which the consortium defines as groups whose cultures and livelihoods are deeply embedded in the land. Estimates vary, but according to the consortium, that number is at least 32 percent globally.

The majority of those areas are conserved and in “good ecological condition,” according to an analysis by the consortium and the UN’s World Conservation Monitoring Centre.

To Indigenous peoples and their allies, this finding is intuitive. “We see ourselves as part of [nature] because it’s life-sustaining,” Aaron Payment, chairperson of the Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians in Michigan, told Vox. “Our very lives depend on living in ecological balance with our natural resources.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22645629/ICCA_IPLC2_with_known_grid__1_.png) New estimates suggest that Indigenous peoples and local communities conserve at least a fifth of all land on Earth. The UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre/ICCA Consortium

New estimates suggest that Indigenous peoples and local communities conserve at least a fifth of all land on Earth. The UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre/ICCA Consortium

“Potential ICCAs” cover more than a fifth of all land on Earth, the report finds. That number is roughly 17 percent if you only include the ICCAs that fall outside areas conserved or protected by countries and private entities. (The consortium uses the word “potential” because these areas are approximated based largely on an analysis of large data sets; only some of them are documented ICCAs.)

Academic research supports the idea that much of the natural habitat within Indigenous land is conserved. One study, for example, found that Indigenous territories harbored more biodiversity than protected areas in Brazil, Australia, and Canada. Another found that at least 36 percent of the world’s remaining intact forest landscapes — continuous tracts of forest and other natural ecosystems — are found within Indigenous territories.

Research has also shown that in some regions, Indigenous control of lands seems to reduce deforestation as much as formal protections, or even more. “Biodiversity is declining more slowly in areas managed by [Indigenous peoples and local communities] than elsewhere,” more than 20 researchers argued in a recent perspective article in the journal Ambio.

While different Indigenous and local groups have different cultures and practices, they tend to share a holistic and human-inclusive view of nature that’s imbued with cultural or spiritual value. It’s this view, in part, that forms the basis for Indigenous land management, which often includes protecting sacred lakes or forests, or creating rules against exploiting certain species./cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22650155/photo11_girl_1.jpg) A young girl with her forest harvest near the Manobo community in the Philippines. Courtesy of Glaiza Tabanao/ICCA Consortium

A young girl with her forest harvest near the Manobo community in the Philippines. Courtesy of Glaiza Tabanao/ICCA Consortium/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22650156/photo2_farmer_hemp.jpg) A farmer in the Pangasananan territory carries a bundle of plant fibers to sell in town. Courtesy of Glaiza Tabanao/PAFID

A farmer in the Pangasananan territory carries a bundle of plant fibers to sell in town. Courtesy of Glaiza Tabanao/PAFID

That’s not to say that Indigenous peoples don’t alter habitats and drive down populations of animals, or that they bear the responsibility for protecting wildlife. But in general, the concept of conservation appears to be more embedded in Indigenous traditions, compared to Western cultures.

That certainly seems true in Pangasananan, an old Manobo word that means “a place where food, medicines, and other needs are obtained,” according to Glaiza Tabanao, a consultant for the Philippine Association for Intercultural Development who contributed to the ICCA Consortium report. It has served as a life-sustaining refuge over the years. During World War II, for example, local families retreated to the woods to escape Japanese soldiers. And in more recent times, they relied on it for food as some of their livelihoods collapsed as a result of the coronavirus pandemic.

“This is what we gain from protecting our territory and its forests,” said Hawudon Sungkuan Nemesio Domogoy, a Manobo leader. “We will surely survive this pandemic.”

Some Indigenous peoples risk their lives for conservation

Nonetheless, the value these communities provide to global conservation efforts — defending their land with their lives, in some cases — is often ignored.

“Much of their contributory effort goes unrecognized and disrespected,” wrote Vicky Tauli-Corpuz, a member of the Kankana-ey Igorot people in the Philippines and the former UN special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples, along with several co-authors, in an article published last year in World Development.

Franklin, the Kashia Pomo tribal leader, told Vox about a local example of this problem. On a recent call to discuss conservation efforts in Sonoma County, a county official (whom he declined to name) mentioned the activities of two local conservation organizations but not of the Kashia Pomo tribe. His tribe has protected thousands of acres of land through parks and easements, Franklin said. “She just completely ignored us,” he said.

In general, most areas that Indigenous peoples protect aren’t considered in tallies by environmental organizations of how much land on Earth is conserved, unless they fall within formal protected or conserved areas. And where these regions do overlap with protected areas, Indigenous peoples are often the de facto custodians of the resident biodiversity — but rarely do they formally govern the areas, according to the ICCA Consortium.

“Indigenous peoples and communities are conserving more than state protected areas, they’re doing a better job than state protected areas,” said Holly Jonas, global coordinator for the ICCA Consortium. “It’s absurd to not have explicit recognition for them.”/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22650162/photo10_farmers_1.jpg) Hawudon Danao and his wife, Victoria, on their farm in the Pangasananan territory, which they left fallow so the soil could regenerate nutrients. Courtesy of Glaiza Tabanao/ICCA Consortium

Hawudon Danao and his wife, Victoria, on their farm in the Pangasananan territory, which they left fallow so the soil could regenerate nutrients. Courtesy of Glaiza Tabanao/ICCA Consortium/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22650166/photo18_river_bamboo.jpg) A river in the Pangasananan territory. Courtest of Glaiza Tabanao/PAFID

A river in the Pangasananan territory. Courtest of Glaiza Tabanao/PAFID

Indigenous knowledge of land management is also often disregarded, said Victoria Reyes-García, a research professor at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and the lead author of the Ambio perspective. In countries like Australia, India, and Bali, Native peoples and local communities have long used tools like controlled burning, grazing, and the construction of canals to sustain themselves and maintain the ecosystems. Yet formal protected areas sometimes put an end to these activities and cause the ecosystems, as they were, to disappear, Reyes-García said. In some cases, that can create problems such as the spread of invasive species.

Making matters worse, these communities tend to lack political power, especially at the national level where most policies relevant to biodiversity are put in place, Reyes-García said. Indigenous advocates also worry that new goals to expand conservation areas under a major international biodiversity treaty, which are being negotiated now, won’t explicitly mention the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities, and their contributions.

Perhaps most troubling is an issue that extends well beyond the topic of biodiversity: Local communities have legal rights to only a small fraction of the land they live on. According to the Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI), a land rights advocacy organization, countries recognize the ownership rights of Indigenous peoples, local communities, and Afrodescendents on just 10 percent of terrestrial land. (RRI is in the process of updating this figure.)

Some Indigenous advocates fear the “30 by 30” global conservation effort

A failure to respect and recognize the contributions of Indigenous peoples has devastating consequences. In the past, governments often uprooted Indigenous communities in the process of creating protected areas, or restricted their traditional activities. By some estimates, 10 million people in developing nations have been displaced by protected areas.

These practices arguably have spilled into the modern age. In Pangasananan, a protected area designated by the Philippine government overlaps with nearly half of the territory. “It’s viewed by the community as problematic,” in part because it “criminalizes” traditional activities like hunting and fishing, according to Tabanao.

Indeed, “our farms and fallow areas are overlapped by the protected area,” said Hawudon Danao, a hunter in the Pangasananan territory. “I hunt in the forests surrounding our farms. My son fishes in the creeks near our farms. Now that these are not allowed, how are we going to live? Where do they suppose we get our food and money for our needs?”/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22650169/photo14_hawudon_tinuy_an.jpg) Hawudon Tinuy-an Alfredo Domogoy, the Manobo chieftain, was named after the Tinuy-an falls (pictured behind him). Courtesy of Glaiza Tabanao/ICCA Consortium

Hawudon Tinuy-an Alfredo Domogoy, the Manobo chieftain, was named after the Tinuy-an falls (pictured behind him). Courtesy of Glaiza Tabanao/ICCA Consortium

That’s why some Indigenous advocates are afraid of what a plan to conserve at least 30 percent of Earth might bring, said Kundan Kumar, director of the Asia program at RRI. One worst-case scenario is that countries and conservation organizations violate Indigenous land rights as they massively expand the world’s network of protected areas — especially considering that many of the remaining biodiversity hot spots are on Indigenous lands. “The fear is there,” Kumar said.

But an alternative scenario is also possible: Countries could seize this moment to support Indigenous and community-led conservation, financially and otherwise. Essentially, this would entail funding these communities to do what they’re already doing, and support efforts to strengthen land ownership, Reyes-García said.

Countries could meet their 30 by 30 goals by including areas conserved by Indigenous peoples and local communities, according to the ICCA Consortium. And a growing body of research shows that one of the best ways to promote conservation is to give legal ownership of land to Indigenous people. Simply acknowledging that much of the world’s intact habitat exists today because — not in spite — of Indigenous peoples would also be helpful, Reyes-García said.

A decade of the Ruggie Principles: World events and looming legislation are forcing investors to step up on human rights

RI’s human rights specialist Gina Gambetta reflects on recent developments on the 10th anniversary of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights

June marks 10 years since the UN Human Rights Council unanimously endorsed the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), known by many as the ‘Ruggie Principles’ – in honour of Harvard academic John Ruggie, who oversaw their creation.

The UNGPs, which are a set of guidelines for States and companies to prevent, address and remedy human rights abuses committed in business operations, have provided a centre of gravity for investor discussion on human rights over the past decade, and are due to underpin a number of major new rules being developed across Europe.

The EU’s Sustainable Corporate Governance Directive, for example, looks set to introduce mandatory human rights and environmental due diligence requirements across the bloc. The proposals currently cover Limited Liability Companies, but European Parliament has approved plans to roll them out to all corporations operating in the EU internal market, including banks and investors.

Directives (as opposed to regulations) allow EU Member States some freedom to decide how they implement rules in their own jurisdictions, and some countries are already coming up with national laws on human rights due diligence that could satisfy – or even influence – the EU requirements.

While France has expected companies to address human rights violations in their supply chains since 2017 through a Duty of Vigilance Law, last month saw Germany’s parliament adopt a Supply Chain Act, which will apply to companies with 3,000+ employees from 2023, expanding to those with more than 1,000 staff by 2024.

The Netherlands’ Bill for Responsible and Sustainable International Business Conduct will have a much lower threshold: it’s targeting companies with 250+ employees, or turnover of more than €40m. Crucially, the Bill – which is still under consideration – aims to include administrative, civil and criminal liability and enforcement.

(For more on due diligence in supply chains, check out last week’s panel on the topic at RI Europe where investor action on human rights was discussed at length.)

Two sets of research this month by the Working Group on Business and Human Rights concluded that, although there has been strong uptake of the UNGPs, as well as increased investor engagement and shareholder voting on human rights, “the rise of mandatory measures [by policymakers] will undoubtedly accelerate both uptake and progress”.

The studies, which offers a series of recommendations on promoting the Principles over the next 10 years, calls on governments to “integrate respect for human rights into the mandate, operations and investment activities of institutions involved in the issuance and management of State pension funds, sovereign wealth bonds and development finance”.

Institutional investors should also require their boards of directors to commit to honouring the UNGPs across their own operations and all investment activities, the report said.

While this level of commitment is still rare, investors are becoming more vocal about human rights, with recent events like Covid-19 and the Black Lives Matter movement throwing the issue into sharper focus in Europe and North America.

Just last week, UK pension funds and finance bodies started pushing for the creation of a “TCFD for social risks”. The calls came as members of the £7tn Find It, Fix It, Prevent It investor initiative, led by UK asset manager CCLA, began lobbying data providers to incorporate modern slavery into ESG ratings. The group also said it would commission “a new rating tool” to help investors tackle the issue.

This AGM season has seen a number of proposals at major banks and investors on racial equity and the treatment of workers during the pandemic (for more on how investors voted on ‘social’ resolutions, see today’s analysis here).

And there has been a flurry of investor activity centred on human rights and geopolitics. Nearly 60 institutional investors are seeking to address “egregious human rights risks” in their portfolios from potential ties to the Xinjiang region of China, where there has been growing controversy surrounding the human rights abuses of Uyghur Muslims. Earlier this month, following February’s military coup in Myanmar, 77 investors – led by Norway’s Storebrand Asset Management, US-based Domini Impact Investments and advocacy group Heartland Initiative – asked firms to outline their business activities in the country and address any potential human rights impacts.

Millions of dollars have been pulled out of companies linked to human rights issues in China, Belarus, Myanmar and Israel, too – a trend led by asset owners in Northern Europe.

Against this backdrop, we’re asking for your views on the state of play for human and labour rights. To tell us whether you think these are material risks for investors, and what the financial world needs to tackle the ‘S’ in ESG, please fill in our survey here. You can remain anonymous and we will publish the results over the summer.

Ground Temperatures Hit 118 Degrees in the Arctic Circle

The ongoing climate crisis is not going to spare Siberia.

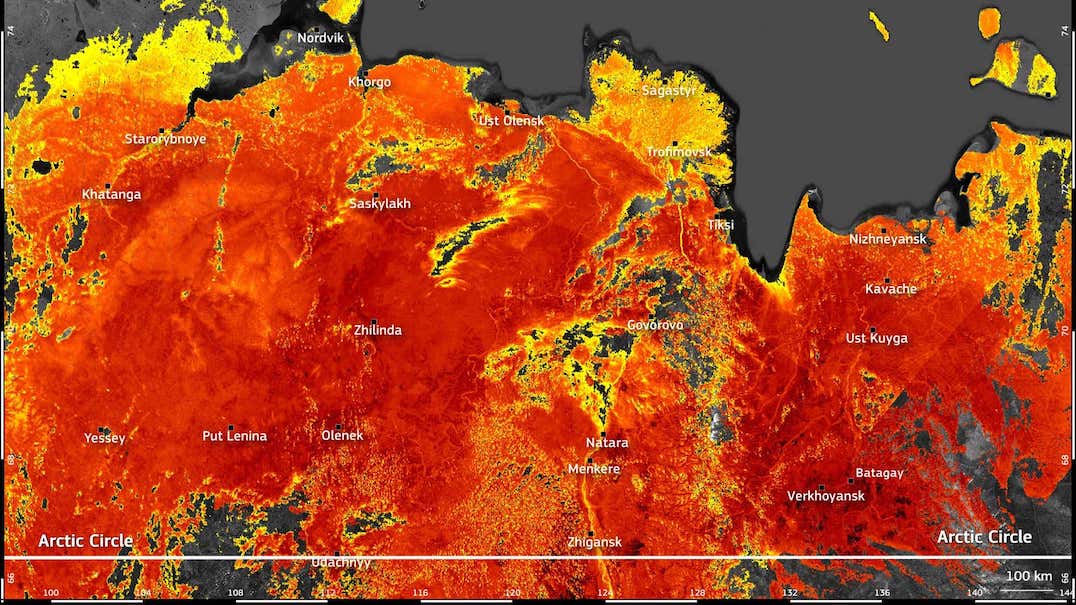

Newly published satellite imagery shows the ground temperature in at least one location in Siberia topped 118 degrees Fahrenheit (48 degrees Celsius) going into the year’s longest day. It’s hot Siberia Earth summer, and it certainly won’t be the last.

While many heads swiveled to the American West as cities like Phoenix and Salt Lake City suffered shockingly hot temperatures this past week, a similar climatological aberrance unfolded on the opposite side of the world in the Arctic Circle. That’s not bizarre when you consider that the planet heating up is a global affair, one that isn’t picky about its targets. We’re all the target!

The 118-degree-Fahrenheit temperature was measured on the ground in Verkhojansk, in Yakutia, Eastern Siberia, by the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel satellites. Other ground temperatures in the region included 109 degrees Fahrenheit (43 degrees Celsius) in Govorovo and 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit (37 degrees Celsius) in Saskylah, which had its highest temperatures since 1936. It’s important to note that the temperatures being discussed here are land surface temperatures, not air temperatures. The air temperature in Verkhojansk was 86 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius)—still anomalously hot, but not Arizona hot.

Photo: MARK RALSTON/AFP (Getty Images)

But the ground temperature being so warm is still very bad. Those temperatures beleaguer the permafrost—the frozen soil of yore, which holds in greenhouse gases and on which much of eastern Russia is built. As permafrost thaws, it sighs its methane back into the atmosphere, causing chasms in the Earth.

Besides the deleterious effects of more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, the permafrost melting destabilizes the Siberian earth, unsettling building foundations and causing landslides. It also exposes the frozen carcasses of many Ice Age mammals, meaning paleontologists have to work fast to study the species that thrived when the planet was much colder. For all the talk of reanimating the woolly mammoth, one’s got to remember: the place they knew is long gone.

The same region also suffered through a heat wave that led to a very un-Siberian air temperature reading of 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius) exactly a year ago to the day from the new freak heat. It’s the hottest temperature ever recorded in the region. It was also in the 90s last month in western Siberia, reflecting that the sweltering new abnormal is affecting just about everywhere. And it’s not just the permafrost suffering; wildfires last year in Siberia pumped a record amount of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, ensuring more summers like this are to come.

Maya Peoples of Belize Win Lawsuit against Belize Government for Violating Land Rights

On June 16, 2021, the Supreme Court of Belize ruled in favor of Maya land rights, upholding the community of Jalacte’s right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) on their customary lands. The court issued a decision in the case, Jalacte Village vs. the Attorney General, ruling that the government breached the Maya Peoples’ constitutional rights, obligating the government of Belize to return the lands that had been taken without the community’s consent and ordering compensation of the equivalent of $3.12 million USD.

The court also found that the government was in breach of a consent order of the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ), the highest international appellate court to which Belize is party. In 2015, the Maya people won an unprecedented victory at that court, in a decision which held that the Maya Peoples of Belize hold customary land rights over the land that they occupy, which is equal to any other form of land ownership in Belize and is constitutionally protected.

“This is very important for all Maya communities. We have a duty to ensure that we protect the rights that we fought for in the court of Belize,” shared the President of the Toledo Alcaldes Association, Domingo Ba, in a press conference following the court decision. Cristina Coc, spokesperson for the Maya Leaders Alliance and the Toledo Alcaldes Association, continued, “One more time, the court of Belize have agreed that the Maya people, have agreed with us, that we own our lands, through our customary use and that we can manage our lands through our customary decision making processes.”

Photo courtesy of Maya Leaders Alliance.

The land in question included 31.36 acres near the Guatemalan border of Southern Belize, where the government had usurped land to expand a road leading to the Guatemalan border and build a border checkpoint. This land is under customary use, and therefore ownership, of the Maya village of Jalacte. The case was originally filed in 2016 by the traditionally elected representative of the village, “First Alcalde” Jose Ical on behalf of the village and by a second claimant, Estevan Caal, on whose land an agricultural border checkpoint was constructed.

The evidence presented to the court is that Caal held “individual customary proprietary right” to parcels of village land used by him based on Jalacte’s collective property rights. At no time were the villagers consulted nor compensated for the taking of the customary land.

In the court’s decision, Chief Justice Arana wrote: “This case should never have arisen. The defendants, that is the government of Belize, were aware of Maya customary land tenure along the route of the road in Jalacte. They were aware that agricultural lands would be damaged and compensation would be needed. They were aware of the Maya fears that the new road would increase pressure on their land tenure by outsiders. And they were aware that it was a constitutional violation to ignore Maya customary rights of Jalacte.”

Photo courtesy of Maya Leaders Alliance.

Since the Caribbean Court of Justice’s 2015 decision, the traditional governance structure of the Maya people, the Toledo Alcaldes Association, with technical support by the Maya Leaders Alliance and Julian Cho Society, have been working with the government, with varying degrees of success, to negotiate an implementation plan for the decision and put it into practice.

“The Toledo Alcaldes Association (TAA) and the Maya Leaders Alliance (MLA) congratulate the village of Jalacte on their resilience and unity as they awaited a decision in their case in the Belize Supreme Court concerning the compulsory acquisition and use of their lands by the Government. One more time, the courts of Belize sided with the Maya People that they are owners of the land they live on. The TAA and the MLA remain committed to a swift and meaningful implementation of the CCJ Consent Order,” the Maya Leaders Alliance shared on social media.

Part of that implementation order is the development of a Free, Prior and Informed Consent protocol. This has been in progress since 2018, when the government of Belize and the Maya people entered into the December 2018 Agreement, considered a roadmap for implementing Maya land rights in accordance with the Caribbean Court of Justice decision was finally reached. This FPIC protocol is based on a previously established consultation framework established by Maya traditional leadership, which has set an example for many Indigenous communities around the world. Although now in a final draft, the FPIC protocol has been unable to advance due to objections by the Belizean government denying the authority of the traditional governance structure of the Toledo Alcaldes Association, although this violates Indigenous Peoples’ established right to self-determine their own forms of governance. The Toledo Alcaldes Association is the traditional form of governance of the Maya people that has evolved over time, uniting the elected and customary leaders of the Maya communities to represent the interest of Maya Peoples.

Spokesperson Cristina Coc notes that cases like Jalacte vs. Attorney General will continue to arise in the absence of an established and agreed upon policy around the protocols for obtaining the community’s Free, Prior and Informed Consent, according to their traditional decision making protocols and governance structures, before development or infrastructure projects are undertaken on their lands.

“Many of the complaints from our villages fundamentally rest on the absence of an FPIC protocol. Many of these incursions by third parties… of the government itself, is because there is an absence of an FPIC protocol that could guide how they should engage with the Maya communities, consult them, seek their Free, Prior and Informed Consent, how that will result in benefit sharing agreements that would be important to preserve the livelihood, health, and enjoyment of the Maya Peoples’ lands,” Coc declared.

Coc emphasized that Maya Peoples continue to seek dialogue and cooperation with the government: “We, the Maya people, the customary leaders, continue to be open to dialogue and good faith relations with the government of Belize. We call on the government to come to the table with us and to meaningfully implement the affirmed rights of the Maya people of southern Belize.”

Siberia, Protest and Politics: Shaman Alexander in Danger

In 2021 a modest long-haired Sakha man named Alexander Gabyshev was arrested at his family compound on the outskirts of Yakutsk in an unprecedented for Sakha Republic (Yakutia) show-of-force featuring nine police cars and over 50 police. For the third time in two years, he was subjected to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization. Some analysts see this medicalized punishment, increasingly common in President Putin’s 4th term, as a return to the politicized use of clinics that had been prevalent against dissidents in the Soviet period. Alexander’s hair was cut, and his dignity demeaned. By April, his health had seriously deteriorated, allegedly through use of debilitating drugs, and his sister feared for his life. A private video of his arrest (possibly filmed by a sympathetic Sakha policeman) shows police overwhelming him in bed as if they were expecting a wild animal; he was forced to the floor bleeding, and handcuffed. Official media claimed he had resisted arrest using a traditional Sakha knife, but this is not evident on the video. By May, a trial in Yakutsk affirmed the legality of his arrest, and a further criminal case was brought against him using the Russian criminal code article 280 against extremism. Appeals are pending, including one accepted by the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

What had elicited such official vehemence against an opposition figure who had dared to critique President Putin but whose powers and influence were relatively minor, compared to prominent Russians like Aleksei Naval’ny? How did a localized movement in far-from-Moscow Siberia become well-known across Russia and beyond?

In his 2018–2019 meteoric rise to national and international attention, Alexander Prokopievich Gabyshev, also called “Shaman Alexander,” “Sasha shaman,” and “Sania,” came to mean many things to many people. For some, he is a potent symbol of protest against a corrupt regime led by a president he calls “a demon.” For others, he has become a coopted tool in some part of the government’s diabolical security system, set to attract followers so that they can be exposed and repressed. Some feel he is a “brave fellow” (molodets), “speaking truth to power” in a refreshingly articulate voice devoid of egotism. Others see him as misguided and psychologically unstable, made “crazy” by a tragic life that includes the death of his beloved wife before they could have children. Some accept him into the Sakha shamanic tradition, arguing his suffering and two–three years spent in the taiga after his wife’s death qualify him as a leader and healer who endured “spirit torture” in order to serve others. Others, including some Sakha and Buryat shamans, reject him as a charlatan whose education as an historian was wasted when he became a welder, street cleaner, and plumber.

These and many other interpretations are debated by my Russian and non-Russian friends with a passion that at minimum reveals he has touched a nerve in Russia’s body politic. It is worth describing how Alexander, born in 1968, describes himself and his mission as a “warrior shaman” before analyzing his significance and his peril.

Alexander’s Movement

Picture Alexander on foot pushing a gurney and surrounded by well-wishers, walking a mountainous highway before being arrested by masked armed police for “extremism” in September 2019. Among over a hundred internet video clips of Alexander’s epic journey from Yakutsk to Ulan-Ude via Chita, is an interview from Shaman on the Move! (June 12, 2019):

I asked, beseeched God, to give me witness and insight….I went into the taiga [after my wife had died of a dreadful disease ten years ago]….It is hard for a Yakut [Sakha person] to live off the land, not regularly eating meat and fish….I came out of the forest a warrior shaman….To the people of Russia, I say “choose for yourself a normal leader,… young, competent”….To the leaders of the regions, I say “take care of your local people and the issues they care about and give them freedom.”…To the people, I say “don’t be afraid of that freedom.” We are endlessly paying, paying out….Will our resources last for our grandchildren? Not at the rate we are going… Give simple people bank credit.. . Let everyone have free education and the chance to choose their careers freely.. . There should not be prisons….But we in Russia [rossiiane] have not achieved this yet, far from it…Our prisons are terrifying….At least make the prisons humane…. For our small businesses, let them flourish before taking taxes from them. Just take taxes from the big, rich businesses….For our agriculture, do not take taxes from people with only a few cows….Take from only the big agro-business enterprises.[1]

In this interview and others, Alexander made clear he is patriotic, a citizen of Russia, who wants to purify its leadership. “Let the world want to be like us in Russia,” he proclaimed, “We need young, free, open leadership.” While he explains that “for a shaman, authority is anathema,” he has praised the relatively young and dynamic head of Sakha Republic: “Aisen [Nikolaev] is a simple person at heart who wants to defend his people, but he is constrained, under the fear of the demon in power [in the Kremlin].” Alexander acknowledges the route he has chosen is difficult, and that many will try to stop him. Indeed he began his “march to Moscow” three separate times, once in 2018 and twice in 2019, including after his arrest when he temporarily slipped away from house arrest in December 2019, was rearrested and fined.

Alexander’s 2021 arrest, described in the opening paragraph, was hastened by his refusal to cooperate with medical personnel as a psychiatric outpatient, and further provoked when he announced he would once again try to reach Moscow, this time on a white horse with a caravan of followers. His video announcement of the new plans, with a photo of him galloping on his white horse carrying an old Sakha warrior’s standard, mentioned that he would begin his Spring renewal journey by visiting the sacred lands of his ancestors in the Viliui (Suntar) territories, “source of my strength.” He encouraged followers to join him, since “truth is with us.”[2] A multiethnic group of followers launched plans to gather sympathizers in a marathon car, van and bus motorcade. Their route was designated to pass through the sacred Altai Mountains region of Southern Siberia. What had begun as a quirky political action on foot acquired the character of a media-savvy pilgrimage.

At moments of peak rhetoric, Alexander often explained that “for freedom you need to struggle.” Into 2021, he hoped to achieve his goal of reaching Red Square to perform his “exorcism ritual.” But his arrests and re-confinement in a psychiatric clinic under punishing “close observation” conditions make that increasingly unlikely, especially given massive crackdowns on all of President Putin’s opponents, including Aleksei Naval’ny and his many supporters. One of Alexander’s most telling early barbs critiqued the “political intelligentsia,” who hold “too many meetings” and do not accomplish enough. He told them: “It is time to stop deceiving us.” Yet he repeated in many interviews that numerous politicians in Russia, across the political spectrum, would be better alternatives than the current occupant of the Kremlin.

Among Alexander’s most controversial actions before he was arrested was a rally and ritual held in Chita in July 2019, on a microphone-equipped stage under the banner “Return the Town and Country to the People.” After watching the soft-spoken and articulate Alexander on the internet for months, I was amazed to see him adopt a more crowd-rousing style, asking hundreds of diverse multiethnic demonstrators to chant, “That is the law” (Eto zakon!) even before he told them what they would be answering in a “call and response” exchange. He bellowed, “give us self-determination,” and the crowd answered, “That is the law.” He cried, “give us freedom to choose our local administrations,” and the crowd answered, “That is the law.” His finale included “Putin has no control over you! Live free!” Only after this rally did I begin to wonder who, if anyone, was coaching him and why. Had he changed in the process of walking, gaining loyal followers, and talking to myriad media? The rally, with crowd estimates from seven hundred to one thousand, had been organized by the local Communist Party opposition. Local Russian Orthodox authorities denounced it and suggested that Alexander was psychologically unwell. Alexander himself simply said, after his arrest, “It is impossible to sit home when a demon is in the Kremlin.”

How and why was Alexander using discourses of demonology? He seemed to be articulating Russian and Sakha beliefs in a society that can be undermined by evil out of control. When he first emerged from the forest, he built a small chapel-memorial in honor of his beloved wife and talked in rhetoric that made connections as much to Russian Orthodoxy as to shamanic tradition. He wore eclectic t-shirts, including one that referenced Cuba and another the petroglyph horse-and-rider seal of the Sakha Republic. Once he began his trek, he wore a particularly striking t-shirt eventually mass-produced for his followers. Called “Arrive and Exorcise,” it was made for him by the Novosibirsk artist Konstantin Eremenko and rendered his face onto an icon-like halo.

Another popular image depicts Alexander as an angel with wings. He has called himself a “Holy Fool,” correlating his brazen actions and protest ideology directly to a Russian iurodivy tradition that enabled poor, dirty, beggar-like tricksters to speak disrespectful truths to tsars. His appeals to God were ambiguous—purposely referencing the God of Orthodoxy and the Sky Gods of the Turkic Heavens (Tengri) in his speeches. During his trek, and in some of his interviews, he has had paint on his face, a thunderbolt zigzag under his eyes and across the bridge of his nose that he calls a “sign of lightning,” derived from his spiritual awakening after meditation in the forest. He has claimed, as a “warrior shaman,” that he is fated to harness spirit power to heal social ills. While his emphasis has been on social ills that begin with the top leadership, he also has been willing to pray and place healing hands on the head of a Buryat woman complaining of chronic headaches, who afterwards joyously pronounced herself cured.

During his trek, on camera and off at evening campsites, Alexander fed the fire spirit pure white milk products, especially kumys (fermented mare’s milk), while offering prayers in the Sakha “white shaman” tradition that he hoped to bring to Red Square for a benevolent ritual not only of exorcism but of forgiveness and blessing. He chanted: “Go, Go, Vladimir Vladimirovich [Putin]. Go of your own free will . . . Only God can judge you. Urui Aikhal!” He expressed pride that some of the Sakha female shamans and elders have blessed his endeavor.

Resonance and Danger

Russian observers, including well-known politicians and eclectic citizens commenting online or on camera, have had wildly divergent reactions to Alexander, sometimes laughing and mocking his naïve, provincial, or perceived weirdo (chudak) persona. But some take him seriously, including the opposition politician Leonid Gozman, President of the All-Russia movement Union of Just Forces. Leonid, admiring Alexander’s bravery, sees significance in how many supporters fed and sheltered him along his nearly two-thousand-kilometer trek before he was arrested. Rather than resenting him for insulting Russia’s wealthy and powerful president, whose survey ratings have plummeted, Alexander’s followers rallied and protected him with a base broader than many opposition politicians have been able to pull together.

As elsewhere in Russia, civic society mobilizers, whether for ecology protests, anti-corruption campaigns or other causes, are becoming savvy at hiding and sharing leadership. By 2021, Alexander had become one of many imprisoned oppositionists, whose numbers throughout Russia have swelled beyond the prisoners of conscience documented when the great physicist Andrei Sakharov was exiled to Gorky in 1985.[3]

Alexander, despite being subdued beyond recognition after multiple arrests, has affirmed that he was hoping for “neither chaos nor revolution, [since] this is the twenty-first century.” He advocates for his followers an “open world, [of ] peace, freedom and solidarity,” one where all people believing in benevolent “higher forces” can find them. His significance is that he is one of the credible politicized spiritual leaders to emerge from Russia in the post-Soviet period, when in the past twenty years the costs of independent leadership have become increasingly dire, self-sacrifice is increasingly necessary, and multi-leveled community building with horizontal interconnections is increasingly risky.

Whether or not defined as religious or shamanic, the bravery and force of individuals willing to risk everything to change social conditions is awesome, transcending and human wherever we find it. Far from insane, these maverick societal shape-changers, tricksters and healers may represent our best power-diversifying hopes against systems that pull in directions of authoritarian repression. Perhaps once-populist power consolidating leaders like Vladimir Putin, who warily watch their public opinion ratings, are insecure enough to understand the deep systemic weaknesses that oppositionists like Alexander Gabyshev and Alexei Naval’ny expose, using very different styles along a sacred-secular continuum. President Putin’s insecurities magnify the importance of all political opposition, creating vortexes of violence and dangers of martyrdom in the name of stability.

Notes

[1] Many Alexander videos have disappeared from the internet, and others are private access. The series “Shaman idet!” [Shaman on the Move], and “Put’ shamana,” [Shaman’s Path] are especially relevant, e.g., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W1jE71TAqZw, July 22, 2019 (accessed 6/18/2021). Shaman idet! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zPrb_1nWXtE, June 12, 2019 was accessed when released and 3/19/2020. See also “Shaman protiv Putin” [Shaman vs. Putin], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tfTEtiqDf6U, June 24, 2019 (accessed 7/3/2019); “Pochemu Kremlin ob”iavil voinu Shamanu—Grazhdanskaia oborona” [Why Did the Kremlin Fight the Shaman- Civil Defense] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M7OVy2ROASQ (accessed 3/15/2020); and Oleg Boldyrev’s BBC interview September 24, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U0LaLhkKj2g (accessed 3/15/2020).

[2] Alexander described plans for the aborted 2021 journey: youtube.com/watch?v=YK0LlFAjx3E (accessed 1/15/2021). See also https://meduza.io/en/news/2021/01/12/yakut-shaman-alexander-gabyshev-announces-new-cross-country-campaign-on-horseback (accessed 6/4/2021).

[3] This Soviet and post-Soviet imprisonment comparison comes from brave opposition politician Vladimir Kara-Murza, himself poisoned twice, in a human rights review for the Kennan Institute, Woodrow Wilson Center, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/event/heightened-political-repression-russia-conversation-vladimir-kara-murza (accessed 6/18/2021).

Inuit-a unique experience of development

BATANI FOUNDATION

June 30, 2021, at 10 am New York time, will be held an international webinar “Inuit-a unique experience of development”, organized by the International Indigenous Fund for development and solidarity “BATANI”.

The Inuit are the indigenous people of the Arctic who live in four countries – Denmark / Greenland, USA, Canada and Russia.

This webinar will aim to introduce Indigenous peoples from different regions of the world to the experiences of the Inuit people in various aspects of their livsfe and work.

At the same time, the uniqueness of such an experience will lie in the fact that the representatives of this people (politicians, businessmen, public and state leaders) will talk about self-government, the social and economic development of their people, and will share their personal experience of participation in the life of their people. The uniqueness of the Inuit experience also lies in the fact that, living in different countries, they were able to build and develop their own self-government bodies, build their own economy, build their own relationships with the governments of these countries.