Russians in Maine find relations strained with friends and family overseas

Disinformation about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has convinced many in Russia to support the regime’s unprovoked war.

YARMOUTH — Pavel Sulyandziga’s former classmates at Khabarovsk State Pedagogical University in Russia’s Far East used to engage in friendly chats about family, gardening and career developments on their WhatsApp group.

Within a week of Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, the Yarmouth resident said the tone changed. A classmate – a doctor of mathematics and physics – started posting praise of Russian troops for what she believed was their heroic effort to save the Ukrainian people from Nazis. Another posted images of the “Z” painted on many Russian military vehicles involved in the brutal invasion, which has become a symbol of support for Vladimir Putin’s war.

When Sulyandziga, an Udege indigenous activist and dissident and asylum recipient who has lived in Maine since fleeing retribution by Putin’s regime in 2015, pushed back, things quickly got ugly.

“I said, what do you mean they are liberating the Ukrainians? None of them are for you, they are all fighting against you,” he recalled. “She wrote back that Putin knows everything, and he is our leader. I was told I was a fascist and a Banderite,” a supporter of the World War II-era Ukrainian nationalist and Nazi collaborator Stepan Bandera, who was assassinated by the KGB in Munich in 1959 and whose name has become the Putin regime’s go-to slur for anyone supporting Ukrainian sovereignty.

“I finally just left the group,” Sulyandziga said. “It doesn’t exist for me now.”

Over the past six weeks, Mainers who immigrated from the Russian Federation have been having exasperating interactions with many of their friends, colleagues and family members back at home who live inside the regime’s disinformation bubble. That’s where up is down, two and two make five, there is no war in Ukraine and Russia’s flawless leader is responsible for saving Ukraine’s people from fascism, rather than destroying their cities, driving 10 million from their homes, and killing an estimated 1,200 civilians in an unprovoked invasion condemned by almost the entire world.

The propaganda bubble is highly effective and driven by Putin’s total control over Russia’s television stations, the closure of the last independent newspapers and radio stations, the blocking of many foreign broadcast and digital news sources and a draconian crackdown against protesters and dissent.

“One of the main reasons it is so effective is because people are already preconditioned to believe these kinds of stories, and not just because the propaganda has been saying these kinds of things for years,” said Anton Shirikov, a doctoral student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who researches Russia’s domestic propaganda. “A lot of people in Russia were and are very upset about how the Soviet Union collapsed, and the reoccurring narrative is that this is all the West’s fault along with the CIA and the traitors who negotiated the collapse. The Ukraine war is just a continuation of that story: Ukraine and NATO plotting against Russia.”

Even people who might be inclined to question the propaganda narrative about the war have incentives not to, Shirikov said. “It would require them to admit that they were lied to for many years and that they were gullible and deceived. It’s not pleasant to admit these things, and when you don’t hear any dissenting voices around you and everyone is saying, ‘This is a just war,’ it’s even harder to start questioning.”

MAY NEVER GO BACK TO HER VILLAGE

Svetlana Bell emigrated to Maine in 1995 from Krasny Yar, a village in the Primorsky of the Russian Far East, 40 miles east of the Chinese border, where most inhabitants are ethnic Udege or Nanai like herself. But she’s found Moscow’s propaganda – which features Russian ethno-nationalism – is highly effective, even from 5,300 miles away in a community with few ethnic Russians that’s closer to Japan.

“I have two sisters there, and they really don’t know there’s a war going on, which for me was a big shock,” Bell said. “They watch television every day, and they don’t talk about the war in Ukraine on the TV news.”

Bell, who is married to former Press Herald reporter Tom Bell and lives in Yarmouth, said she tried to explain to one sister what was really happening in Ukraine. “She didn’t believe me and was very angry at me for telling her this because she said Russia supports peace around the world. They are taken in by the propaganda, and the phone calls became really tense because of the disagreement over what was happening.

“I don’t want to call them or argue with them anymore,” she said.

There are dissenters. A man Bell knew in Krasny Yar, whose wife was in Ukraine, saw a photograph Bell posted on social media of her attending an anti-war protest in Portland and contacted her via WhatsApp. “He was so glad to learn that I was protesting the war, and he had found a way to learn what was going on there,” Bell recalled. “I don’t know how he was able to get the information, but for most people it is very difficult.”

Later she saw a photograph on social media she found devastating. Villagers had gathered in traditional indigenous clothing and used a drone to take a picture of themselves standing in a “Z” formation around a Russian flag. “I was very disgraced to see that,” she said. “Maybe after this, I will never be able to go back to this village.”

Several Russian immigrants declined to speak to the Press Herald for fear of getting their family members in trouble or because it was too painful to do so. One couple from Russia’s North Ossetia region in the Caucasus Mountains who live in Greater Portland agreed to speak anonymously about their communications with friends in larger cities there.

“Our relatives are very smart and intelligent people who never bought anything they saw on TV, so it’s easy to talk to them because they see things as we do,” the wife in the couple explained, noting YouTube and some other platforms still function in Russia, allowing people who want to seek out information from the outside to do so. “But they say when they try to explain to the people around them what is going on, to convince them that everything they see on (Russian regime-controlled) TV has nothing to do with reality, it’s like talking to a brick wall.”

Her husband has tried talking with his former high school classmates, but he gets too frustrated to continue. “They just respond with the slogans they see on TV, with exactly the same words, like they’re reading from a script,” he said. “I know I can’t make a big hole in that wall, but just a little hole would be nice.”

They say younger people in larger cities are generally not taken in by the propaganda because they don’t watch television. “They go into TikTok and Instagram and Facebook so they don’t buy it,” the wife said. “But people who live in small towns and villages don’t have access to the internet or, if they do, often don’t know how to use it. So their only access is via television and radio, and that puts them so far from the reality of the war.”

‘THEY WATCH ONLY RUSSIAN NEWS’

Victoria Liashenko emigrated from Russia six years ago and lives in Portland with her American husband. Her parents live in Tatarstan, about 600 miles east of Moscow, and even though her father’s family are ethnic Ukrainians, when it comes to the war they’re living, as she puts it, in “an illusion.”

“They watch only Russian news, which tells them that nothing is happening and that they need to trust the government,” she said. “There has been some arguing between us. They don’t understand why they should have to fight for freedom; they just want to leave things as they are. They are used to this world.”

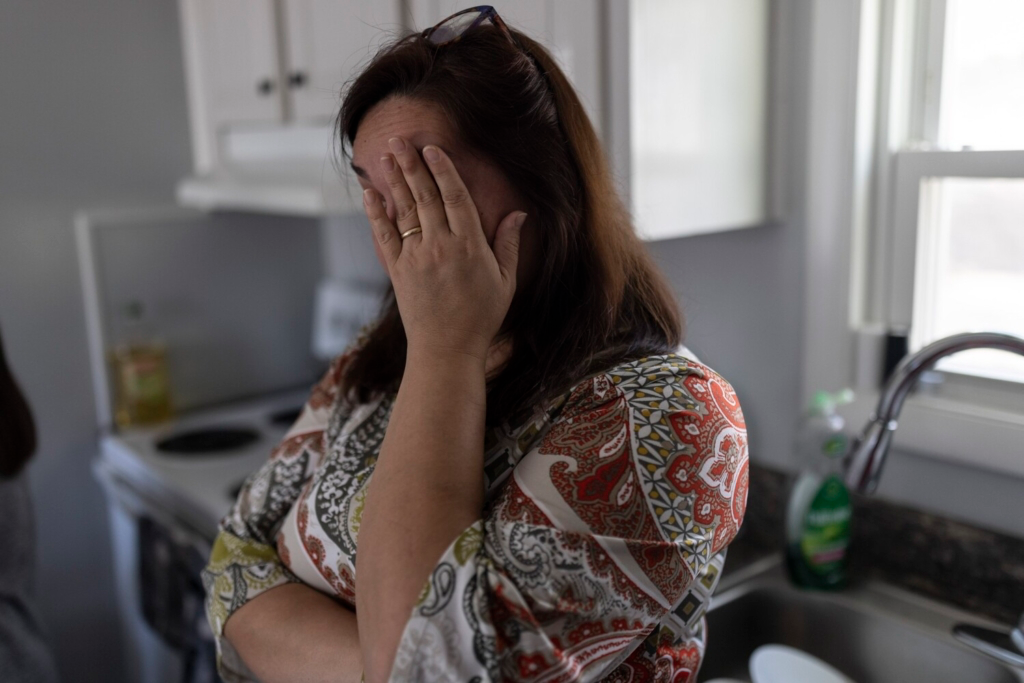

Her parents also fear Putin’s regime. “I posted something on Instagram against the war, and my mom called me crying worried that the KGB will show up at the house,” Liashenko, who participated in the first protest of her life in Boston last month, recalled. “I told her that’s not true, but they are so scared.” They’ve never met her husband, and she wonders when they ever will.

None of the Russians the Press Herald spoke to for this story had any hope that their countrymen would rise up to overthrow Putin because a large majority accept and support his nationalist agenda, tacitly or actively.

“There’s a minority of people who don’t like Putin’s regime, but most of the people who could have risen up already left Russia,” Sulyandziga said. “I don’t think anything major is going to happen. The only possibility is a palace coup.”

Staff writer Eric Russell contributed to this story.