“We are the Hongana Manyawa. We defend the forests and mountains because we think of them as our parents.”

Uncontacted tribal people face total destruction from mining for electric car batteries

Uncontacted tribal people in Indonesia who choose to live in the rainforest far from outsiders could be wiped out by a massive nickel mining project. Many are already on the run from mining which is tearing up their ancestral lands and damaging their rivers.

An estimated 300 to 500 uncontacted Hongana Manyawa people live in the forested interior of the island of Halmahera. Huge areas of their territory have now been allocated to mining companies, and in some areas the excavators are already at work.

The project is part of Indonesia’s plan to become a major producer of electric car batteries, by mining and smelting nickel and other minerals – a plan into which international companies like Tesla are already pouring billions of dollars. French, German and Chinese companies are involved in mining in Halmahera. The uncontacted Hongana Manyawa, despite contributing nothing to climate change, now risk being wiped out by the industrialized world’s switch to electric cars. The Hongana Manyawa need our urgent support.

Guardians of their forest

The Hongana Manyawa – which means ‘People of the Forest’ in their own language – are one of the last nomadic hunter gatherer tribes in Indonesia, and many of them are uncontacted.

They have a profound reverence for their forest and everything in it: they believe that trees, like humans, possess souls and feelings. Rather than cut down trees to build houses, they make their dwellings from sticks and leaves. When forest products are used, rituals are performed to ask permission from the plants, and offerings are left out of respect.

The Hongana Manyawa root their whole lives to the forest, from birth to death. When a child is born, the family plant a tree in gratitude, and bury the umbilical cord underneath: the tree grows with the child, marking their age. At the end of their lives, their bodies are placed in the trees in a special area of the forest that is reserved for the spirits.

If there is no more forest, then there will be no more Hongana Manyawa.

Hongana Manyawa man

Providing for themselves almost entirely from hunting and gathering, the Hongana Manyawa are nomadic; setting up home in one part of the forest before moving on and allowing it to regenerate. They have unrivalled expertise in the Halmahera rainforest, hunting wild boar, deer and other animals and maintaining a close connection with the sago trees – now threatened by deforestation from mining – which provide their main source of carbohydrate. They also have incredible medicinal knowledge and can treat many sicknesses with local plants, although this has become increasingly difficult following the new diseases brought by forced contact and resettlement in villages.

It’s more convenient for me to keep moving because the food is much more diverse and available, I can go hunting regularly. Permanently staying in the village is very uncomfortable and there is a lack of food.

Hongana Manyawa man

Avoiding contact to stay alive

This incredible footage, taken in 2021, shows an uncontacted Hongana Manyawa man, throwing things and singing angrily to ward off the outsiders who have come into his territory:

The arrival of the mining companies is just the latest threat to the Hongana Manyawa and their land. In recent decades, Indonesian governments have repeatedly tried to force contact onto the Hongana Manyawa, with the aim of stopping their nomadic way of life and evicting them from their ancestral forest home. They say this is to “civilize” them: they have tried to settle the Hongana Manyawa and have built Indonesian-style houses for them. The Hongana Manyawa say these new houses, with roofs made of metal sheets rather than palm leaves, made them feel “like animals in a cage”.

One Hongana Manyawa woman told Survival:

We are so happy living by the forest with different kinds of meat and food, where we can collect roof materials so we can replace the zinc roof the government has built for us.

Hongana Manyawa woman

As with uncontacted tribes the world over, forced contact has proved disastrous for the Hongana Manyawa. They were immediately exposed to diseases to which they had no immunity – from the late 1970s to the early 1990s, terrible outbreaks of diseases which the Hongana Manyawa refer to as “the plague” affected the newly-settled villages, leading to widespread suffering and even death.

We had many different diseases when first settled, some of the sickness led to deaths, some people had fever that went on for days and nights and endless coughing for days and even weeks.

Hongana Manyawa man

The contacted Hongana Manyawa also serve as convenient scapegoats for the police, who frequently blame them for crimes they have had nothing to do with. Several of them have been imprisoned for murders they did not commit and have languished in jail for many years.

It’s better to live in the forest so we don’t get accused of these things. We feel unsafe and many of the men moved into the forest and then came to get their wives and families. Some are deep in the forest…they are deeply traumatized.

Hongana Manyawa woman

Far from being respected for their unique and self-sufficient ways of living, the Hongana Manyawa experience severe racism and are regularly described by Indonesian officials and the media as ‘primitive’. There is a widespread belief that they would benefit from ‘integration’ into wider society: a belief that comes with disastrous and deadly consequences.

Many Hongana Manyawa are now living in government-built villages. Many others – traumatised by the government’s forced settlement attempts, like other peoples around the world who have experienced forced contact – have returned to their forest.

The uncontacted Hongana Manyawa have made it clear time and time again that they do not want to settle or have outsiders coming into their forest. They are very much aware of the dangers – including fatal epidemics of disease – which forced contact brings. As with the uncontacted Sentinelese tribe of India, it is little wonder that they are defending their lands and shooting arrows at those who force their way in.

But now they face the threat not just of being forced out of the forest that sustains them, but of seeing it all destroyed by corporations rushing to provide a supposedly ‘sustainable’ and “environmentally friendly” lifestyle to people thousands of miles away.”

‘Green’ mining threatens the lives of uncontacted tribal people

The greatest threat to the Hongana Manyawa today comes from a supposedly ‘green’ industry.

Their rainforest sits on lands rich in nickel, a metal increasingly sought after as an ingredient in the manufacture of electric car batteries. Indonesia is now the world’s largest producer of nickel, and Halmahera is estimated to contain some of the world’s largest unexploited nickel reserves. Nickel is not essential for these batteries, but now that the nickel market is booming, mining companies are homing in and tearing up huge swathes of rainforest.

The uncontacted Hongana Manyawa are on the run. Without their rainforest, they will not survive. These cars are marketed as ecofriendly alternatives to fossil fuel powered cars, but there is nothing ecofriendly about the way nickel is being mined in Halmahera.

It goes without saying that uncontacted tribes cannot give their Free, Prior and Informed Consent to exploitation of their land – which is legally required for all ‘developments’ on Indigenous territories under international law.

Nevertheless, Weda Bay Nickel (WBN) – a company partly owned by French mining company Eramet – has an enormous mining concession on the island which overlaps with Hongana Manyawa territories. WBN began mining in 2019. Since then, huge areas of rainforest which the Hongana Manyawa call home have already been destroyed. The company plans to ramp up the mining to many times its current rate and operate for up to 50 years.

We still have a sacred forest but there are not many animals there. Now it is peatlands, it is no longer good forest.

Hongana Manyawa man

The Indonesian government claims that nickel mining is “critical for clean energy technologies” yet coal-fired power stations are being constructed at IWIP to process the nickel. The International Energy Agency estimates that 19 metric tons of carbon are released for every metric ton of nickel smelted and there is evidence from a similar project in Sulawesi of this leading to respiratory diseases for locals. Not only is this mining (accompanied by roads, smelters and other huge industrial projects) devastating the Hongana Manyawa’s rainforests, it is also polluting the air and damaging the rivers. The processing of nickel is often highly toxic, involving a host of chemicals which produce almost two metric tons of toxic waste for every metric ton of ore processed.

Survival is fighting against false solutions to the climate crisis, which are destroying Indigenous lands and lives.

They are poisoning our water and making us feel like we are being slowly killed.

Hongana Manyawa woman

Eramet, Tesla and connected companies

International companies are involved, directly or indirectly, in the mining of uncontacted Hongana Manyawa land.

WBN is a joint venture between several companies, but French company Eramet is part-owner and responsible for the mining itself. Eramet prides itself on its environmental and human rights credentials, claiming that it will “set the standard” and “be a benchmark company” when it comes to human rights. Yet it continues to mine on the territory of the uncontacted Hongana Manyawa.

Survival has learned that German chemical company BASF is also planning to partner with Eramet to build a refinery in Halmahera and that a possible location for this may be on uncontacted Hongana Manyawa territory. This would be devastating for the uncontacted Hongana Manyawa in the area, who are already in hiding from mining.

Watch this Tribal Voice interview with two Hongana Manyawa elders, decrying the destruction of their rainforest and stating plainly that they do not give consent for nickel mining companies to take their land:

Survival has been told that uncontacted Hongana Manyawa are now fleeing further and further into the rainforest, traumatized by the attacks on their forests and way of life.

Trees are gone and replaced with the big road, where giant machines go in and out making noise and driving the animals away.

Hongana Manyawa woman

Tesla, the world’s largest electric vehicle company, has signed contracts worth billions of US dollars to buy Indonesian nickel and cobalt for its batteries. Its CEO Elon Musk has also had high level negotiations with the Indonesian government to open an electric car battery factory in the country. Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo has even offered Tesla a ‘nickel mining concession.’

Tesla’s Indigenous rights policy states: “For all raw material extraction and processing used in Tesla products, we expect our mining industry suppliers to engage with legitimate representatives of indigenous communities and include the right to free and informed consent in their operations.”

Yet Tesla has now signed deals with Chinese companies Huayou Cobalt and CNGR Advanced Material, both of which have links to nickel mining in Halmahera. While supply chains are secretive and often obscure, Tesla’s interests in Indonesia and the scale of the planned mining in Halmahera make it likely that nickel mined from Halmahera could well end up in Tesla cars.

I do not give consent for them to take it…tell them that we do not want to give away our forest

Hongana Manyawa woman

Demand for electric cars is driving the destruction of uncontacted people’s lands.

Rather than destroying yet more of the natural world, and the people who defend it, in the name of combating climate change, we should be supporting uncontacted tribes to defend their rainforests and their land rights; they are the guardians of the green lungs of the planet.

We the Hongana Manyawa, do not want a mine to come, because it will destroy our forest. We will really defend this forest. If the forest is damaged, then where will we live?

Hongana Manyawa man

Take Urgent Action for the Hongana Manyawa

The Hongana Manyawa are running out of forest and running out of time. They desperately need international support to stop the destruction of their homelands before it’s too late.

The Hongana Manyawa’s land rights must be recognised. Survival is calling for the declaration of an emergency zone for the uncontacted Hongana Manyawa. Around the world, Survival has successfully campaigned for the land rights of uncontacted tribes, defending them from outsiders bringing in deadly diseases and devastating development projects which could destroy them.

We are calling for:

– Eramet and the other companies mining in Halmahera, to immediately abide by international law and stop mining and other developments on the lands of uncontacted tribal people.

– Tesla and other car companies to publicly commit to ensure that none of the nickel or cobalt they buy ever comes from the lands of the uncontacted Hongana Manyawa in Halmahera.

– The Indonesian government to establish an ‘Uncontacted Tribe No-Go Zone” to protect the uncontacted Hongana Manyawa and their territories.

With your support, the territories of the uncontacted Hongana Manyawa can be protected from mining so that they can continue to live as they choose on their own land.

I want to share my knowledge with my grandchildren and those who want to learn how to eat and live in the forest.

Hongana Manyawa man

Act now to help The Hongana Manyawa

Yes, I will take action!

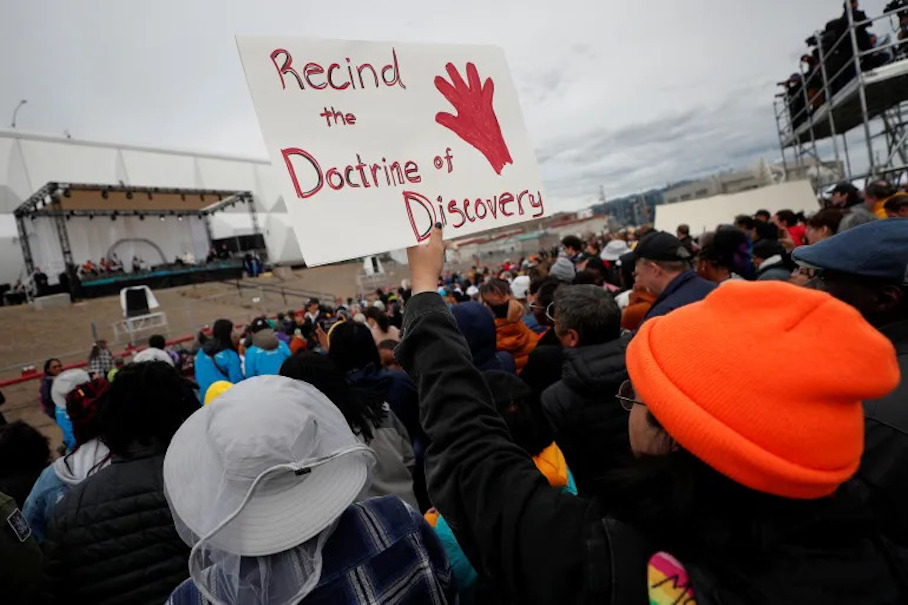

Vatican rejects ‘Doctrine of Discovery’ justifying colonialism

After decades of demands by Indigenous people, Vatican ‘repudiates’ theories that backed colonial-era seizure of lands.

The Vatican has rejected the “Doctrine of Discovery”, a 15th-century concept laid out in so-called “papal bulls” that were used to justify European Christian colonialists’ seizure of Indigenous lands in Africa and the Americas.

In a statement on Thursday, the Vatican’s development and education office said the theory (PDF) – which still informs government policies and laws today – was not part of the Catholic Church’s teachings.

It said the papal bulls were “manipulated for political purposes by competing colonial powers in order to justify immoral acts against Indigenous peoples that were carried out, at times, without opposition from ecclesiastical authorities”.

“In no uncertain terms, the Church’s magisterium upholds the respect due to every human being,” the statement reads. “The Catholic Church therefore repudiates those concepts that fail to recognize the inherent human rights of Indigenous peoples, including what has become known as the legal and political ‘doctrine of discovery’.”

For decades, Indigenous leaders and community advocates had urged the Catholic Church to rescind the Doctrine of Discovery, which stated that European colonialists could claim any territory not yet “discovered” by Christians.

The papal bulls played a key role in the European conquest of Africa and the Americas, and their effects are still felt by Indigenous people.

Calls to rescind the Doctrine of Discovery grew louder last year when Pope Francis made a trip to Canada during which he apologised for the Catholic Church’s role in widespread abuses that took place at so-called residential schools.

Between the late 1800s and 1990s, more than 150,000 Inuit, First Nation and Metis children across Canada were taken from their families and communities and obligated to attend the forced-assimilation institutions, which were rife with physical, psychological and sexual violence.

The Haudenosaunee External Relations Committee said at the time of the pope’s residential school apology that more action was needed from the church – notably, the revocation of the papal bulls.

“An apology to Indigenous Peoples without action are just empty words. The Vatican must revoke these Papal Bulls and stand up for Indigenous Peoples’ rights to their lands in courts, legislatures and elsewhere in the world,” the committee said in a July 2022 statement.

Indigenous leaders welcomed Thursday’s Vatican statement, even though it continued to take some distance from acknowledging actual culpability.

Phil Fontaine, a former national chief of the Assembly of First Nations in Canada who was part of the delegation that met with Pope Francis at the Vatican before last year’s trip and then accompanied him throughout, said the statement was “wonderful”.

He said it resolved an outstanding issue and now put the matter to civil authorities to revise property laws that cite the doctrine.

“The Holy Father promised that upon his return to Rome, they would begin work on a statement which was designed to allay the fears and concerns of many survivors and others concerned about the relationship between their Catholic Church and our people, and he did as he said he would do,” Fontaine told The Associated Press news agency.

“Now the ball is in the court of governments, the United States and in Canada, but particularly in the United States where the doctrine is embedded in the law,” he said.

“Today’s news on the Vatican’s formal repudiation of the Doctrine of Discovery is the result of hard work and advocacy on the part of Indigenous leadership and communities,” Canadian Justice Minister David Lametti wrote on Twitter. “A doctrine that should have never existed. This is another step forward.”

The Doctrine of Discovery was cited as recently as a 2005 US Supreme Court decision involving the Oneida Indian Nation and written by the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

On Thursday, the Vatican offered no evidence that the three papal bulls (Dum Diversas in 1452, Romanus Pontifex in 1455 and Inter Caetera in 1493) had themselves been formally abrogated, rescinded or rejected, as Vatican officials have often said.

But it cited a subsequent papal bull, Sublimis Deus in 1537, that reaffirmed that Indigenous peoples should not be deprived of their liberty or the possession of their property, and were not to be enslaved.

Cardinal Michael Czerny, the Canadian Jesuit whose office co-authored the statement, stressed that the original papal bulls had long ago been abrogated and that the use of the term “doctrine” — which in this case is a legal term, not a religious one — had led to centuries of confusion about the church’s role.

The original papal bulls, he said, “are being treated as if they were teaching, magisterial or doctrinal documents, and they are an ad hoc political move. And I think to solemnly repudiate an ad hoc political move is to generate more confusion than clarity”.

He stressed that the statement was not just about setting the historical record straight, but “to discover, identify, analyse and try to overcome what we can only call the enduring effects of colonialism today”.

Michele Audette, an Innu senator who was one of the five commissioners responsible for conducting the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls in Canada, told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation that the announcement left her in disbelief.

“It’s big,” she said in an interview on CBC Daybreak. “That doctrine made sure we did not exist or were even recognised … It’s one of the root causes of why the relationship is so broken.”

NEW UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT RULE PROPERLY RECOGNIZES TRIBAL GOVERNMENTS

In December 2022, the United States Supreme Court adopted changes to its rules. The Native American Rights Fund (NARF) is happy to report that in those changes is a big win for Indian Country, one for which NARF actively advocated on behalf of tribal nations. Specifically, in the 2023 rules, tribal governments will be allowed to file longer amicus briefs, in recognition of their status as governmental entities. This change comes after NARF submitted comments to the Court urging that tribal governments be treated equally to federal, state, and local governments.

In 2019, the Court adopted rules that reduced the length allowed for many amicus briefs filed with the Court. However, briefs filed by federal, state, and local governments were permitted a much higher word count. Notably, tribal governments were not included in the list of governmental entities exempted from the restrictions. Therefore, during the next revision process (held in 2022), NARF submitted comments addressing this disparity.

NARF’s comments to the Court detailed why the change was right and needed. On a basic level, including tribes in the list of governmental entities is consistent with how other branches of the federal government treat tribes. However, it also addresses several unique issues faced by tribal interests in the Court. For example,

- The higher word count for governments recognizes their unique interests in participating as amici curiae out of respect for their inherent sovereignty and/or their exercise of governmental authority. Like other governments, tribes have an interest in advocating for their powers and advancing the unique interests of themselves and their members.

- Cases related to tribes’ authority, treaty rights, and resources frequently do not include tribes as parties. In those cases, tribes participate as amici, and it is critical that tribal perspectives be fully heard on those issues. The United States does not always adequately represent tribal interests in a case. In fact, the positions of the United States and tribes are not always aligned.

- Similarly, in the context of Federal Indian Law, cases often address foundational constitutional law principles. Facilitating tribal participation allows tribes to provide important information and context to the Court.

NARF appreciates the opportunity to comment on the Court’s proposed rule changes and commends the Court on making this important change to properly recognize tribal sovereignty.

First Nations police launch human-rights complaint against Ottawa over funding

Police chiefs presiding over First Nations police forces in Ontario have launched a human-rights complaint alleging that the federal government is placing reserves in crisis by failing to deliver adequate funding.

The claim, which was obtained by The Globe and Mail, was filed last week at the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) by police chiefs at nine First Nations police forces in Ontario. It also has the support of a group representing 22 First Nations police forces in Quebec. Altogether, the groups in both provinces make up the vast majority of self-administered Indigenous police forces in Canada.

The police chiefs in the claim allege that Ottawa has allowed“chronic underfunding and under-resourcing of the safety of Indigenous communities,” which they say is discriminatory because it contributes to high crime in communities that were promised equitable levels of safety to communities outside reserves.

The claim says Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his cabinet have not followed through on public pledges to bring in legislation to improve security by enshrining First Nations policing programs into law as an essential service, which could lead to greater levels of funding.

“Despite these commitments made by the leader of this country, the complainants now find themselves in a manufactured public safety crisis,” reads the 32-page filing to the CHRT. In the complaint, the police chiefs say that inflexible federal civil servants are crafting deals through “negotiation tactics aimed at forcing First Nations to sign unfair, discriminatory funding agreements.”

The complaint seeks damages of $40,000 per reserve resident as well as orders directing Ottawa officials to negotiate deals in better faith.

The police chiefs’ claim echoes a similar case over alleged underfunding of the Indigenous child-welfare system. A CHRT ruling in 2016 led to a $40-billion compensation plan announced five years later. That complaint also sought $40,000 for each affected person.

Last year, the CHRT ruled that government underfunding of the Mashteuiatsh Police Service in Pekuakamiulnuatsh First Nation in Quebec was discriminatory.

The new complaint amounts to an indictment of the federally runFirst Nations and Inuit Policing Program (FNIPP), a 30-year-old funding formula created to put more police on Canada’s reserves by splitting costs with provinces.

The federal government now pays about $200-million each year into the program, which has created nearly 40 Indigenous police forces. But police chiefs leading most of these organizations support the new rights complaint. The federal Department of Public Safety did not immediately reply to e-mailed questions about the legal action.

The police chiefs said in interviews that frustrations have been building for years because funding is discretionary and never guaranteed by government. They argue the program’s short-term deal-making processes also means that Indigenous police forces may find themselves without any money at all if bargaining for a new deal breaks down.

“We have a federal government with this First Nations and Inuit Policing Program that essentially allows the contract to expire without any mechanisms to continue the funding – that’s unconscionable,” Police Chief Kai Liu,who runs the Treaty Three Police Service across a sprawling part of northwestern Ontario, said in an interview.

Police Chief Liu, who is also president of the Indigenous Police Chiefs of Ontario, is the lead complainant in the CHRT claim. He said his own police force is one of three in Ontario whose funding agreements expired at the end of the fiscal year this past weekend without any arrangements assuring future funding being put in place. Negotiations with the federal government are continuing for a new deal.

Federal civil servants, he said, have told him that government funds cannot be used to pay for lawyers who act for Indigenous communities and policing services in these negotiations. The money also comes with restrictions that it cannot be used to create police squads such as tactical units or canine teams.

He and other forces are demanding change. Such positions “make no logical sense when it comes to policing,” said Chief Liu. He said, the lack of a deal in his jurisdiction risks demoralizing overworked officers who are already struggling to respond to emergency calls in a timely manner.

While police response times are at issue across rural Canada, First Nations can face much higher crime rates than other communities. Last September, a man killed 11 people and wounded 18 others in a mass stabbing centred on the James Smith Cree Nation in northern Saskatchewan. That violent rampage drew national attention and raised questions about why nearest police were posted at a detachment 45 kilometres away.

The CHRT complaint points out that Mr. Trudeau promised new policing measures when he visited the James Smith in the aftermath of the rampage. “Prime Minister Trudeau announced a renewed commitment to ensuring First Nations benefit from the same standard of policing available to non-Indigenous communities,” the complaint says.

In 2019, the final report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls urged the federal government to replace the FNIPP with legislation that would “immediately and dramatically transform Indigenous policing.” Later that year, Mr. Trudeau wrote a mandate letter directing his cabinet ministers to develop that law but federal officials last month told The Globe they cannot give any timelines.

The police chiefs at several First Nations forces say they cannot wait for a bill. “It’s like saying the cheque is in the mail,” said Chief Shawn Dulude of the Akwesasne Mohawk Police Service.

He leads the First Nations police chiefs’ organization in Quebec and said the 22 forces intend to intervene at the human-rights tribunal in support of the Ontario complaint.

“I’m afraid that we’re going to see a third mandate go by and what they promised us will not have materialized,” he said, referring to Mr. Trudeau’s Liberal government.

Last month, a Globe investigation into First Nations policing in Saskatchewan revealed how the FNIPP is not reaching residents of many reservesin that province. Citing The Globe’s reporting, the new rights complaint says this is just one example of a program that has gone off track.

Julian Falconer, the lawyer acting on behalf of the First Nations police chiefs in Ontario, says the FNIPP was created with the stated goal of ensuring that residents of reserves are as safe as Canadians living outside of them.

But federal officials have stopped using this language, he said, and that’s significant. “We call it the phantom policy. It’s concealed from public view.”

Sámi rights must not be sacrificed for green energy goals of Europe

- Last week, the European Commission released the Critical Raw Materials Act for minerals used in renewable energy and digital technologies.

- It mandates that EU countries should be extracting “enough ores, minerals and concentrates to produce at least 10% of their strategic raw materials by 2030,” and part of that looks likely to come from mines on Indigenous Sámi land.

- Mines already sited there have caused pollution, devastated ecosystems, poisoned reindeer forage, and taken away their reindeer grazing areas. “How can this transition be sustainable if it destroys our land and violates our Indigenous and human rights?” a new op-ed asks.

- This post is a commentary. The views expressed are those of the author, not necessarily of Mongabay.

Growing up in Gällivare/ Váhtjer, a Swedish village in Sápmi, north of the Arctic Circle, the threats facing Sámi people were a daily reality.

We are Europe’s only Indigenous people, but colonialism means our territory, Sápmi, is split across four countries: Sweden, Finland, Norway and Russia.

But across these national borders, the same pressures bear down on us, from mining to forestry and wind farms.

For outsiders’ commercial gain, our land has been seized, our people displaced, and the reindeer herding that’s been the foundation of our lives for millennia, eroded.

Adjacent to my village is Malmberget, a scene of deep mine iron ore extraction, and a little over 100 kilometers away is Kiruna, the world’s largest underground iron mine. Both are owned by Luossavaara-Kiirunavaara AB (LKAB), the 100% state-owned Swedish mining company.

Kiruna is one of the nine out of 12 mines in the north of Sweden which are on Sámi land. These mines – as well as the infrastructure accompanying them – have caused pollution, devastated ecosystems, poisoned the lichen that our reindeer survive on, and taken away our reindeer grazing areas.

More mining

Now a new danger has emerged.

European Union policymakers want to secure the ‘critical raw materials’ which its Member States need for the green energy and digital transitions. They’ve identified 30 raw materials as being of vital strategic and economic importance.

By 2030, according to a report based on the draft text of the European Commission’s Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), which was just released on March 16, EU countries should be extracting “enough ores, minerals and concentrates to produce at least 10% of their strategic raw materials by 2030.”

This will mean that they want to increase mining on our land.

Mineral rush

In January, LKAB announced that it had found Europe’s largest deposit of rare earth elements north of Kiruna. They calculated that the deposit contains at least one million tons of rare earth oxides, minerals used in everything from electric vehicles to wind turbines to mobile phones.

As the rush to extract these and other critical raw materials intensifies, the Sámi people are being told that we have to ‘co-exist’ with mining. Yet co-existence always means us moving and changing our traditional way of life: a way of life that has existed alongside nature for a long, long time.

We are also told that these operations are sustainable and part of the green energy transition. But how can this transition be sustainable if it destroys our land and violates our Indigenous and human rights?

The United Nations has criticized the Swedish, Finnish and Norwegian governments for violating Sámi rights in the past. For example, in 2020 the UN Committee on the elimination of Racial Discrimination condemned Sweden for ignoring Sámi rights by establishing a mine in Rönnebäck. It also called on Sweden to revise its mining legislation to ensure that it respects and complies with the Sámi people’s rights, saying that Swedish law didn’t provide the Sámi reindeer herding community with a real opportunity to have the legality of the mining project tested before the courts.

And earlier this month, the Norwegian government was forced to apologize to Sámi reindeer herders for violating their rights by issuing licenses to operate wind farms on the Fosen peninsula, after the Supreme Court ruled in the herders’ favor.

The overwhelming message in these cases – and throughout Sámi history – is that we must have a say in any decisions that fundamentally affect our lives.

As such, our right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) to any mining, wind farms or forestry on our land should be sacrosanct: FPIC is a fundamental right, not merely a principle, as the Swedish government claims.

The EU must also recognize and support this right. A good start would be by enshrining FPIC in the CRMA.

Polarization in Siberia: Thwarted Indigeneity and Sovereignty

Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer updates her monograph Galvanizing Nostalgia? to explore why many in the republics are against Russia’s war in Ukraine. Drawing on long-term fieldwork in Sakha, Tyva and Buryatia and with diaspora communities, she outlines an uneven legacy of revitalization and grievances in relation to the Kremlin and its policies.

As we rethink our approaches to Russia, its colonizing history, and its current leaders’ aggressions against Ukraine, we must also consider vast parts of Russia’s eastern lands that are understudied and too often misunderstood. A Sakha (Yakut) engineer explains that most of his mining friends abhor Russia’s war in Ukraine. A creative gaming company founded in Yakutsk has decamped to Thailand with hundreds of its IT workers’ families. COVID crisis call centers in some republics have switched to mobilization information, fielding calls mostly from frantic women trying to save their husbands and sons. Women protesters in Yakutsk braved cold and jail to stage an antiwar dance chant (ohuokhai) in the main square; many were arrested.

Such narratives challenge surveys and publicity asserting that most “Russians” (Rossiyane) patriotically support the war or are not courageous enough to oppose it. Resistance, including arson against military recruitment offices, has diversified. Are non-Russians inside the republics, given their disproportionate mobilization, the exception to generalizations about citizen support for Putin’s fatal regime? Could Russia’s faltering “Federation” fall apart? These and other hot issues regarding the peoples of Siberia are explored in my Galvanizing Nostalgia? Indigeneity and Sovereignty in Siberia, featuring long-term anthropology fieldwork in three republics, Sakha, Buryatia and Tyva. I argue that Northeastern territories, disproportionately influenced by climate change, hold important keys to Russia’s wealth, development, and stability.

One theory about the timing of the invasion of Ukraine suggests that Putin hoped for a diversionary victory that could unite Russia’s multiethnic peoples against an artificial outside enemy, staving off domestic political, economic and ecological discontent. Instability and dissent have been building in the republics since Putin came to power and abrogated Yeltsin’s 1990s negotiated bilateral treaties. Polarization has grown, although secessionist claims were rare until the Ukraine war, and today are expressed mostly by diaspora politicians without relatives inside who could be punished.

Sakha: Resource Rich and Pivotal

The Sakha Republic, said to contain most of Mendeleev’s table, is crucial for Russia’s war economy. Its Putin-appointed yes-man leader Aisen Nikolaev has conformed to central pressures, including at a Northern Forum conference in late 2022, where a Soviet-style panel celebrating “100 years of republic sovereignty within Russia” lauded a history of mutually beneficial federal relations enabling “massive investment projects, social programs, increased infrastructure, resource innovation, spiritual development and the growth of unique culture.”

“But this paternalistic propaganda is belied by resentments against resource extraction without environmental protections and by economic recentralization that has robbed the republic of their cuts of diamond profits.”

Sakha citizens use an old Sakha word “Il Darkhan” (Elder-Leader) for their head of government to cleverly avoid the forbidden term President, and are proud of their Turkic language. The Sakha have regained a slim majority in the republic over the plurality Russian and Ukrainian population, in addition to Even, Evenki and Yukaghir Indigenous minorities. Many republic citizens, sometimes calling themselves Yakutiane, dream of greater negotiated sovereignty and hide their sons in disgust against a war they refuse to gloss as a righteous “military operation.”

Buryatia: Gerrymandered and Struggling

Buryatia, impoverished and gerrymandered, has a legacy as a once powerful Mongolic Buddhist state on the border with Mongolia. The dismemberment of “Greater Buryatia” began in the early Soviet period precisely because Russian central authorities perceived Buryat-Mongols as a serious threat. Today the Buryat constitute about a third of the Republic of Buryatia. They lost under Putin two satellite regions, Ust-Orda and Aga, sequentially amalgamated by rigged referenda in 2006 and 2008 into neighboring Irkutsk and Chita (now Zabaikalsk Krai) regions. Powerless to resist, many Buryat nonetheless resent land claims, privatization, non-negotiated development, and propaganda since 2014 that has proclaimed them “Putin’s Militant Buryats.” While Buryatia is known for high education rates and pervasive Russification, Buryats have fought for their language rights and the ecology of Lake Baikal together with some Russian allies. Their first President Leonid Potapov in the 1990s was a Buryat-speaking Russian. The initial post-Soviet period enabled conditions for successful revival of shamanic and Buddhist spirituality in the republic, and also for an influx of Chinese and other outsiders.

Tyva: A Borderline State with Demographic Advantages

Tyva (Tuva), nestled in the Altai-Sayan Mountains, came into the Soviet Union as a mere oblast at approximately the same time as the Baltic States. From 1921-44, the country of Tannu (Taiga)-Touva had its own monetary unit called aksha, and collector-worthy stamps. With longer borders than the current republic, it had been a protectorate of Mongolia in the early twentieth century. It became a republic inside Russia (RSFSR) quite late, 1961. Empowered by demographics but not mineral wealth, the republic is well over three quarters Tyvan. Many Russians fled its territory after anti-Russian unrest as the Soviet Union dissolved. In the early 1990s, a party called “Khostug Tyva” (Free Tyva) advocated separation from Russia, but cooler heads prevailed, such as that of activist Kadyr-ool Bicheldei, and Tyva accepted its economic dependency on Moscow. It is native son Sergei Shoigu has become Putin’s friend and Minister of Defense. Many of its impoverished unemployed youth have become soldiers on the front lines of the Ukraine war, despite their Buddhist backgrounds. Sadly, some became targets of seemingly racist Donetsk republic militias’ brutalization.

Soviet-style repressions and Revitalization

Cultural and civilizational ties among citizens of the eastern republics have been alternately ignored or considered threatening at various levels of government. Practicing divide and rule strategies, Soviet authorities repressed pan-Turkism, pan-Mongolism and homegrown Eurasianism without valuing their potential influence in defusing chauvinist types of more narrow nationalism. All three of these crossover ideologies have blossomed in the post-Soviet period with horizontal contacts, fluctuating degrees of official support, attempted cooption and understanding. People are nostalgic for various pasts, differentially interpreted and used in leaders’ rhetoric in various ways. Multiple and situational identities have flourished as many Siberians have become increasingly cosmopolitan. Particularly fascinating have been cross-republic revivals of shamanic and Buddhist activism, enabling all three republics to open themselves to mutual cultural pilgrimage, tourism and international spiritual seeking. The popular movement of shaman Alexander represents an example of the Putin regime’s return to Soviet-style repression of dissent using punitive psychiatry.

The China factor

A controversial aspect of politics and economic dependencies involves the degree of China’s influence in Russia’s eastern territories. While the Chinese presence is significant, it is crucial for analysts to be geographically nuanced, differentiating regions from sub-regions, republics from oblasts, and Siberia from the Far East, two separate mega-zones in official Russian conceptions. China has historical claims on certain territories north of the Amur River, but is far less interested in occupying all of Siberia in the Western sense. The presence of seasonal Chinese traders and workers in the Sakha Republic hardly makes it a target of territorial expansion. A Power of Siberia pipeline running to China does not give the Chinese territorial rights, nor does their observer status in the Arctic Council.

Ethnonational fault lines

Further interethnic complexities are built into Russia’s legal definition of “Indigenous people,” which diverges from international usage. Russian law defines its “Native” (korennye, from ‘rooted’) peoples as only “small-numbered” (under 50,000), while United Nations definitions incorporate larger non-state ethnonational groups with long-recognized homelands, such as the Sakha, Buryat, Tyvans, Khakas and Altaians. While recognition as Indigenous can be beneficial in the international context, it is less commonly used by peoples with named (titular) republics. A two-tiered system exists within the republics for “small-numbered” peoples, such as the Even, Evenki, Yukaghir, Todja, Akha and Soyot, some of whom complain of dual assimilation pressures. These are compounded by restrictive 2022 registration procedures, and new decrees that mobilize previously exempt Siberian Natives into the war in Ukraine. Many groups claim victimization with discourses raging along ethnonational lines. This influences how non-Russian elites in the republics think about their relationships with the federal center.

Russia’s valiant but dispersed opposition and its multinational “matryoshka doll” composition reveal fault lines in Russian society. While wide-ranging protests have been repressed, hopes for cultural, personal and societal dignity have not. Each republic within Russia valorizes different legacies, and has had various relationships with Moscow in the past century. Some are more polarized than others, especially those in the North Caucasus. Russia’s society is more fragile than many analysts realize. Whether Russia eventually will fragment along the lines of its republics, or hold at least partly together in a real federation through negotiation and nested sovereignty depends on its peoples pulling back from dangers of violence that result from mutual polarization. Siberians merit being on the map of international awareness, for their striking multiethnic histories and their strategic significance for Russia’s survival.

As the most enterprising and morally attuned of Russia’s multiethnic intelligentsia and workers abandon the country, recovering intertwined cultural, societal, political, ecological and economic conditions that could heal Putin’s authoritarianism becomes increasingly unrealistic. Russia may spiral out of any single leader’s control.

Dmitry Berezhkov. Indigenous peoples is an integral part of the Arctic security

Today the Arctic security is threatened on all fronts, from extractive industries development and toxic contamination to the world’s fastest climate change. Recent political tensions between the West and Russia and the start of the war in Ukraine are putting Arctic security in a condition similar to the most hectic times that Arctic stakeholders experienced 40 years ago and earlier. And once again, as decades ago, the most vulnerable are becoming the most affected ones, including the Arctic indigenous communities.

In Russia, the Arctic is a home to multiple indigenous peoples. According to Russian official statistics, about one-third of the small-numbered indigenous peoples of the Russian North, Siberia, and the Far East live in the Arctic environment.

The Russian indigenous movement is a relatively young one. It emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union based on international law and the rapidly developing democratization of regional processes in 1990s Russia.

The Arctic has always been a focus of the Russian indigenous self-determination agenda. Following the wave of Gorbachyov’s democratization, the Russian Government agreed to include the newly established Russian indigenous peoples’ organization, RAIPON, as a Permanent Participant in the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy from the Russian side in 1991. As a result, the Arctic became the only region where Russia recognized indigenous peoples as valuable stakeholders of the international development agenda.

Further established Arctic Council became a unique interstates organization that recognized indigenous peoples as almost equals in decision-making. Unfortunately, it was the only Russian experience, as nowhere else Russia considered indigenous peoples as equal partners or even stakeholders in decision-making.

In general, negotiations with indigenous peoples within the Arctic Council have always been used by Russia as a presentational model for foreign officials and investors rather than as an actual pilot project for building partner relations with indigenous peoples.

But since the returning Vladimir Putin to the Kremlin in 2012 and especially after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the Russian Government tightened its control over the non-governmental sector and ethnic organizations, so today, RAIPON’s role has primarily been reduced to rubber-stamping government decisions.

After the war in Ukraine started in February 2022, the Western segment of the Arctic Council officially put the Arctic cooperation on hold. As a result, the Arctic Council and its unique model of interstate negotiations, with the involvement of the Indigenous organizations in decision-making, stepped into a zone of turbulence. Later it was announced the Council would ‘implement a limited number of projects that do not involve Russian participation. Meanwhile, Russia, who ironically holds the Council’s two-year rotating chairmanship, is doing it in complete solitude.

The Russian invasion influenced the country’s indigenous peoples on various fronts: through division of the indigenous movement, censorship, and silencing of indigenous representatives who opposed the war or even protecting their environmental rights, as Russian authorities now widely consider such actions as an antistate activity.

As the Russian-Ukranian conflict rages, the following questions are being raised: How will the conflict influence Russia’s and Arctic indigenous communities? How will it impact the states’ approach to indigenous peoples’ political development? How does it reflect on Arctic international relations and the Arctic Council, which has been perceived as one of the last major West-involved international platforms in which the Russian Federation remained a significant partner?

Notably, the seven Western states decided to boycott the Arctic Council without consultations with the Permanent Participants. For indigenous organizations, it signals a tectonic shift in regional governance and international legal practice and jeopardizes the hard-won slot of indigenous voices at the Arctic decision table.

Russia’s attack on Ukraine provoked a split among Arctic indigenous organizations themselves. The two-decade efforts to build up and strengthen relationships were torn down overnight. RAIPON openly aligned with the Government and supported Vladimir Putin’s actions in Ukraine. Saami Council suspended formal relations with Kola Sámi in the Murmansk region. At the moment, the Russian Government turned the Arctic Council’s indigenous agenda into a platform for aggressive propaganda under the RAIPON flag.

It is hard to tell precisely what Russia’s current indigenous policy is being aimed at. While seemingly aimed at the conservation of certain elements of indigenous cultures and symbolic markers of national identity like folklore, museums, languages and others, it takes the focus away from more substantive discussions regarding the reclamation of indigenous territories, livelihoods, natural resources, and self-government, and most importantly, from the discourse of rights per se. Instead, indigenous issues are handled in an increasingly paternalist manner.

Before February 2022 country’s strong paternalism was tempered by the presence of international actors in the region. Today, the Russian state is relentlessly nullifying any indigenous self-governance progress by tightening the state’s control over the lands and resources.

At the same time, we continue to believe that the region’s future cannot be discussed without Indigenous Peoples’ direct participation. Instead of fitting indigenous peoples into an existing system, states must change institutional arrangements and transfer control over indigenous lands and development agenda to indigenous institutions and actors. The legal framework must accommodate, advocate, and even take on indigenous forms instead of holding the implementation of Indigenous Peoples’ fundamental rights. The practice of indigenous rights must be in the control of indigenous people themselves.

Then, there is always a concern about how governing structures within indigenous groups truly reflect the interests and concerns of the indigenous communities. The internationally recognized implication is that the state must engage with self-organized indigenous representative bodies and with grassroots community members to avoid the cultivation of pro-government indigenous politicians and ensure the representation of the true indigenous interests. To magnify indigenous voices and support human rights in general, Arctic stakeholders, including states, must be ready to stand up as an ally with indigenous peoples organizations or their initiatives which governments do not control in one way or another.

What is known today is that the Arctic is heading into dark times. The region lost its status as a space immune from political tensions and matters of security and militarization. Arctic Council lost one member and is currently considering adapting its work to the new reality. The Russian Federation lost its place in the Arctic Council and its partner status in a number of strategic spheres. Permanent Participants are losing their collective voice and a hard-won seat at the table. Russian indigenous peoples lost a vital platform to address the international community, while RAIPON lost the legitimacy to represent the country’s indigenous voices.

We all have already heard Putin’s idea of creating a multiply diverse world that will be separated into “zones of responsibility,” like Germany was divided after the Second World war. And this is an attractive concept for many. At the same time, we need to remember that there are universal values and challenges like human rights, climate issues, our connected environment, which through their nature, are not dependent on the concrete political regime in the country.

We also heard some international voices which propose to return to the pre-Russian-Ukrainian-war model in the Arctic negotiations “to keep a channel of free-from-conflict negotiations with Russia”. This is natural when conflict sides, trying to avoid the “hot phase”, seek peaceful solutions. This is a natural form of compromising when military confrontation is at stake. At the same time, we cannot tolerate such compromises again at the expense of the most vulnerable stakeholders, including indigenous peoples.

Dmitry Berezhkov, member of the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (ICIPR), 10.03.2023

One year after Russia’s Ukraine invasion, circumpolar diplomats take stock

TORONTO — Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last year upended almost 30 years of Arctic cooperation, but it’s also brought northern allies even closer together, a group of diplomats from the world’s circumpolar countries told a Canadian conference on Wednesday.

By Eilís Quinn

“It’s been a very dramatic year for the world, for Europe and for North America,” Jon Elvedal Fredriksen, Norway’s ambassador to Canada, told the Arctic360 conference in Toronto.

“Having said that, I think it’s also important to realize that we have energized a lot of partnerships between friends in the North. I think we’ve all demonstrated that we are eager to work with each other and have a lot of themes, problems and challenges we need to work with in the Arctic regardless of what’s going on elsewhere.”

The seven western states, often referred to as the Arctic 7, suspended their participation in the Arctic Council’s work in March 2022 in protest against Russia’s invasion saying the war undermined many of the founding principles of the Arctic forum, which include sovereignty and territorial integrity based on international law.

In June, the A7 announced they’d resume work together on some of the forum’s projects, but without Moscow.

Heidi Kutz, Canada’s senior arctic official and the director general of Arctic, Eurasian, and European Affairs at Global Affairs Canada, says this was an important signal to the international community and northern residents.

“Like-minded states reactivated their cooperation,” Kutz said. “It can’t be business as usual with Russia, and that’s obvious because of the action that they took, but in June of last year we’ve been working across our partnerships and reactivated all of those … and I think that was important.”

Strengthening the western alliance

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine this year has transformed the security picture in Europe and prompted both Sweden and Finland to apply for NATO membership.

Their applications were approved and the accession protocols for both countries were signed on July 5. Twenty-eight of the 30 member countries have ratified the protocols so far. Turkey and Hungary are the remaining two countries that need to do so.

“What the Russian aggression on Ukraine brought forth is that I don’t think NATO, and the western alliance, has ever been so closely linked,” Roy Eriksson, Finland’s Ambassador to Canada, said. “We kind of found each other again.”

Opportunity for closer ties with Canada

Eriksson said that includes bilateral relations between Ottawa and Helsinki.

“I don’t think Finnish-Canadian relations have ever been so close as they are now,” he said.

Norway’s Fredriksen agrees.

“Cooperating with Russia was the centre of Norwegian High North policy. There is always limited capacity, and with that focus, there was perhaps less attention on what we could do with Canadian partners, or partners from Alaska or other partners in the western Arctic.

“In the current situation, there can be no business as usual with Russia, so there should be capacity now to look at some of those partnerships and personally, I think we should spend a lot more time moving that forward.”

The Arctic360 conference is put on by the eponymously named think tank.

This year’s theme is Tilting the Globe: Accelerating Cooperation, Innovation and Opportunity and focuses on business development and the changing geopolitical context in the North.

Instead of planting trees, give forests back to people

Forests flourish under community control, and NASA has the satellite imagery to show it.

It might sound counterintuitive, but empowering locals to manage forests is an excellent way to preserve them. That strategy can even bring dwindling forests roaring back, NASA Earth Observatory’s recent “image of the day” shows us.

NASA published a set of maps yesterday showing the incredible recovery Nepal’s forests have made over the past several decades thanks to a plan to put nearby communities in charge of conservation. You can see thin forest cover in the early 1990s, followed by a lush resurgence by the late 2010s. Forest cover almost doubled across the country between 1992 and 2016, the satellite imagery shows.

“Once communities started actively managing the forests, they grew back mainly as a result of natural regeneration,” Jefferson Fox, deputy director of research at the East-West Center in Hawaii, says in NASA’s blog post. Fox was on the NASA-funded research team that documented the remarkable comeback.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24423195/nepaltreecover_2016.jpeg)

In the late 1970s, a World Bank report issued a dire prediction that forests would mostly vanish from Nepal’s hills by 1990. Its plains would be similarly barren by 2000. After being nationalized decades earlier, forests were rapidly falling to agriculture and chopped down for firewood. But the country changed course in 1978, when it launched a community forestry program.

The plan was to put local groups in charge of managing large areas of land. That allowed people to use the forests to gather food or firewood, for example. But they were also charged with developing plans to make sure those resources stayed plentiful. It was in their best interest to keep forests healthy.

Now, some 22,000 local groups manage roughly 2.3 million hectares (5,683,424 acres) of community forests in Nepal. That’s about 3 million households maintaining around one-third of all of Nepal’s forests. And they’ve had incredible results. Forest cover in the community-governed area of Devithan grew from 12 percent to 92 percent over a few decades.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24423385/nepaltreecoverzoom_2016.jpeg)

This kind of success isn’t necessarily unique to Nepal. In the Amazon rainforest, Indigenous management of land has also curbed deforestation. That’s something to keep in mind now that tree planting schemes have become all the rage with brands and billionaires who want to show that they care about our planet and climate change. And world leaders have committed to conserve 30 percent of the world’s land and waters by 2030.

Sure, forests are in dire straits across the world, and repairing them brings the added benefit of trapping carbon dioxide that would otherwise heat up the planet. But so many forestry projects fail without community buy-in. Seedlings die and trees are cut down, often because there isn’t a plan in place to manage them for the long haul.

In worst-case scenarios, Indigenous peoples and other residents have been kicked off their lands in the name of conservation. What decades of experience and research actually show us is that they were the best stewards of the forest in the first place.

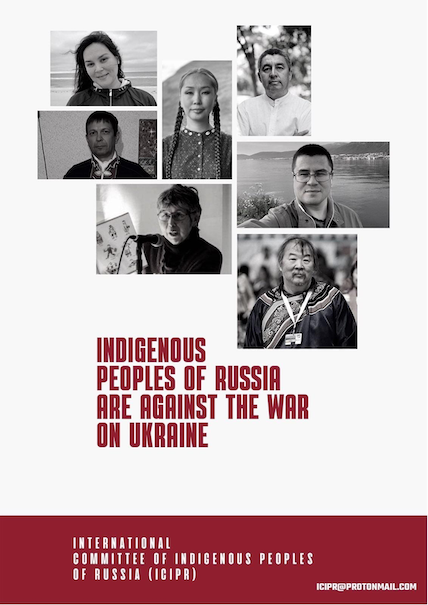

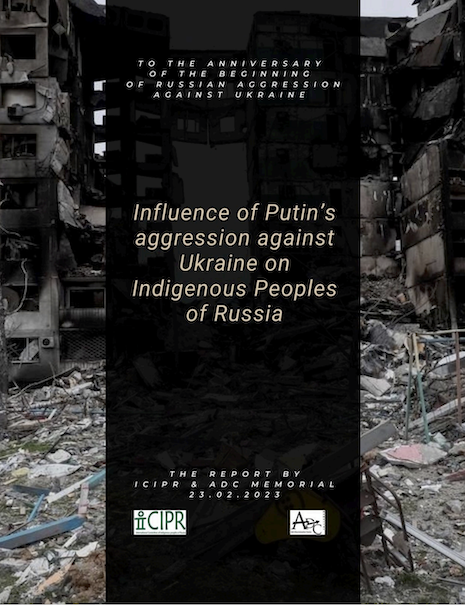

Influence of Putin’s aggression against Ukraine on Indigenous Peoples of Russia

Dear colleagues, brothers and sisters,

Tomorrow is the first anniversary of the bloody Russian aggression against Ukraine, unleashed by the imperial policy of dictator Putin. This war has already cost the Ukrainian nation tens of thousands of lives, including the lives of the indigenous peoples. This war is a tragedy for the Ukrainian Nation.

In this war, are also dying representatives of the indigenous peoples of Russia succumbed to state propaganda and went to the war as soldiers of the Russian army. We, in cooperation with the Anti-Discrimination Centre Memorial, decided to prepare a report on the impact of this injustice war on the indigenous peoples of Russia to show that this war is also a tragedy for small-numbered indigenous nations of Russia.

The first edition of the iCIPR report on the war’s influence on the indigenous peoples of Russia was published on 24 August 2022. You can see it at https://indigenous-russia.com/archives/27991.

Here is the second edition.

Dmitry Berezhkov – editor-in-chief of the Indigenous Russia information center, member of the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (iCIPR)

The report by the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (iCIPR) and the Anti-Discrimination Centre Memorial to the anniversary of the beginning of Russian aggression against Ukraine.

Second edition, 23 February 2023

Introduction

After Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012, the Russian Government turned its attention to civil society organizations. Draconian laws enacted since 2012 regulate the work of organizations engaged in activities deemed political by the Government. The constant harassment of these organizations by the authorities has made it next to impossible to openly and freely discuss Indigenous Peoples’ rights, especially land rights and self-determination. A particularly worrisome aspect was the accelerating expansion of extractive industries on Indigenous Peoples’ traditional lands, regulated and encouraged by the Government, without their Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) and paying neglect attention to the environmental standards.

As a result, today, the once vibrant Indigenous activist movement in Russia has been reduced to a handful of people. Those activists must be extremely careful, as anyone who openly questions the authorities’ political and economic choices is at risk of criminal prosecution. A number of prominent Indigenous rights defenders left the country[1], fearing for their safety. Some who stay in Russia experience arbitrary criminal prosecution initiated by the state or extractive industries.

After the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the repressive Russian legislation was much strengthened, and critical Indigenous voices fear persecution can no longer effectively stand up for their rights and publicly criticize the Government, its proxy organizations, and crony extractive businesses.

Indigenous soldiers in the war

The war’s most direct and unfortunate impact on Indigenous peoples is the participation of Indigenous soldiers in the Russian army fighting in Ukraine. Many experts and mass media have repeatedly pointed to the disproportionate conscription of Russian ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples into the army compared with the titular population of Russia. For example, according to the “Ethnic and regional inequalities in the Russian military fatalities in the 2022 war in Ukraine”[2] report, a soldier drafted into the war from Buryatia is about 100 times more likely to die than a resident of Moscow.

The other visible example is the drafting campaign in the Udege indigenous community Gvasugi in the Russian Far East (Khabarovsk krai). According[3] to the Russian Ministry of Defense, Sergey Shoigu, only about one percent (300 thousand persons) of the total Russian mobilization resource (25 million people) were mobilized. At the same time, in Gvasugi village, where only two hundred persons live, 14 men were mobilized[4]. That consists[5] of 11 percent of the total male population of the village and about 30 percent of the mobilization resource (men who could be sent to war according to their age and other standards).

Hundreds of deaths of Indigenous soldiers from Chukotka, Khabarovsk Krai, Tyva, Yakutia, and other Russian regions have already been confirmed[6]. However, the total number of Indigenous soldiers’ deaths is difficult to estimate as many Indigenous peoples in Russia have Russian names, making it impossible to distinguish them from non-Indigenous servicemen in open databases. The Russian Government does not publish reliable data on fallen soldiers and makes no statistics on Indigenous Peoples’ share in its rare information reports[7].

Most Indigenous Peoples officially recognized[8] by Russia are numbered several thousand or even hundreds of people. So while any loss of life is a tragedy, for small-numbered Indigenous Peoples, it could be a question of their very survival. Tragically, many who return home alive will likely suffer from injuries and mental health problems. At the same time, Russia’s healthcare infrastructure in remote areas where most Indigenous peoples live has minimal capacity[9] to address these issues.

In many poor remote areas where Indigenous Peoples live, even in the usual time, the military contract service was one of the few paid jobs available and better paid than many other public jobs. Today the Russian Government is attracting[10] disadvantaged and underserved people for the war in Ukraine, promising them a salary several times higher than the average wage in the region while does not provide[11] potential recruits with realistic information about what to expect in the war.

Still, a lot of male Indigenous Peoples’ representatives attempted to avoid forced mobilization of the Russian army. While some[12] tried to disappear into forests pursuing their usual traditional activities, others had to leave[13] Russia, which again will negatively reflect on the general statistics of their small-numbered nations.

Influence of the war on the social and economic life of Indigenous communities

Since the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, sanctions by Western governments were quickly followed by foreign businesses choosing to leave[14] the Russian market. International trade links between Russia and the West based on the exchange of raw materials mined mainly on the lands of the indigenous peoples of the Russian Arctic, Siberia, and the Far East for Western goods and technologies were almost destroyed during the war.

In an economy like Russia’s one, closely linked to international trade, this led to immediate economic consequences felt by many within Russia. The country is already experiencing shortages of some essential supplies like medicines[15] and aircraft[16] produced by Western companies. The lack of such goods is hitting remote Indigenous communities especially hard, as many are only accessible by air transport much of the year and cannot receive high-level medical services in remote villages. According to our indigenous informants’ reports from Russia, their communities have already met with the problem of runaway inflation and rising prices of consumer goods, especially in remote villages which do not have year-round access to the rest of Russia, except by air transport.

The sanctions influence various aspects of indigenous peoples’ life differently in Russia. For example, indigenous hunters in Siberia were unable[17] to sell peltries, while fur hunting is the basis of their traditional economies. The cause of the problem is that Russia has lost access to the European fur auctions, which were the primary consumers of Russia’s furs.

In other regions, indigenous communities met with the problem[18] of a lack of access or high prices on the western-produced equipment, which has long been used in the daily lives of Indigenous reindeer herders, hunters, fishermen, including snowmobiles, off-road transportation, satellite communications etc.

The war and Russian extractive industry: lowering environmental and human rights standards

Using the “wartime” and sanctions pretext, Russian authorities and mining businesses are subsequently lowering[19] environmental standards in the country to “support the Russian economy”. According to the Russian Socio-Ecological Union (RSEU)[20], this trend includes: reducing mandatory requirements for ensuring ecological safety; complicating access and depriving citizens of the right to participate in issues related to nature and habitat protections; reducing state oversight over the activities of environmentally hazardous facilities; reduction or cancellation of the legislative ban on economic development of protected areas and requirements for forest conservation; extension of deadlines for federal environmental projects and state programs beyond the responsibility of the current generation of officials.

One of the most dangerous tendencies is the intentional shrinking of the State Environmental Impact Assessment (SEIA) requirements. Aleksandr Fedorov, a member of the Russian Ministry of Natural Resources and Ecology’s Public Council, mentioned[21] several weakening procedures for the state environmental assessments initiated by state or business: reduce the scope of specific SEIAs, dilute the range of issues addressed by SEIAs, decrease the importance of SEIAs in decision-making; limit civil society participation during SEIAs and other assessments; depriving citizens of the right to organize their own public environmental impact studies.

For example, in November 2022, in Lovozero village in the Murmansk region where Russian Sami live, the regional Government organized public hearings[22] on changing the status of the Seydyavr State Nature Reserve. This Natural Reserve has created near Lovozero village around the sacred Seidozero lake, where several Sami historical and religious significance sites are located.

According to the regional Government, the main idea[23] of the reorganization is the increasing tourist traffic to Seydozero and the possibility of rare-earth metals mining for Lovozero mining and processing plant on the Natural Reserve territory. Expanding the potential of rare-earth metal mining became necessary for Russia due to Western sanctions on the supply of microelectronics, which Russia needs[24] primarily to develop its military industry. Thus, the reorganization of the reserve threatens by mass tourism on the sacred lake (to which the Sami themselves have limited[25] access), on the one hand, and pollution of the territory due to the expansion of mining operations in this area on the other hand.

The weakening of the SEIAs’ procedures led to formalizing public hearings, now the almost only approach for local communities, including indigenous ones, to participate in decision-making regarding new development projects on their communal lands. Considering the Lovozero example, the local authorities gave only six days[26] after the public hearings for local residents to study a rather complex, technical 170-page document of the Natural Reserve reorganization rationale and present their opinion.

Similar nominal public hearings procedures are applied to other indigenous communities around the Russian Arctic, Siberia and the Far East, including among reindeer herders[27], who rarely have the opportunity to visit villages to participate in the public hearings.

The other significant tendency is escaping Western mining companies, investors and buyers from Russia and their replacement by Russian, Chinese, and other non-Western businesses. For example, this summer, president Putin raised the stakes[28] in his economic war against the West and signed a decree that seized complete control of the Sakhalin-2 gas and oil project in Russia’s Far East to force the oil Shell company out of Russia. Today the Sakhalin-2 project operates by Russian natural gas state monopoly Gazprom which has been repeatedly proven to violate[29] the rights of indigenous peoples.

That means Russian indigenous communities lost their opportunity to apply to Western mining businesses on international human rights and environmental standards, which they follow more thoroughly than Russian or non-Western companies.

The other challenge connected to the war is today’s impossibility of organizing independent research on mining business influence on indigenous communities or verifying the Russian stakeholders’ information. The country is closed to international field visits. During the war, several international institutions, including the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA)[30] and the Council of Europe Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, canceled their country visits.

Victimization of civil society institutions

The war in Ukraine has provided the Russian Government with a new opportunity to tighten an already minimal civic space in Russia. Soon after the start of the war, Russian authorities blocked[31] the last remaining independent media outlets in Russia, Russian language media based abroad, and access[32] to various social media outlets. The Government continues[33] its destructive campaign to expel from the country the independent human rights, environmental and expert organizations that, in the past, have provided invaluable assistance to Indigenous communities in defending their rights to lands, resources, and self-determination. As a result, the overwhelming majority of Russia’s Indigenous population lost access to independent sources of information except for the government ones, while indigenous communities lost the opportunity to apply for help from independent media and human rights organizations.

The criminal prosecution of Segey Kechimov[34] could be considered an example.

Sergey Kechimov is a Khanty indigenous person who lives with his wife near the sacred Khanty lake Numto in Khanty-Mansiisk autonomous region. This region is the most oil-rich in Russia. One of the biggest Russian oil companies, “Surgutneftegas,”[35] has been exploring and extracting oil near the lake since 2012. Since then, Sergey Kechimov has been trying to protect Khanty’s traditional lands against oil pollution near his reindeer herding camp. In 2017 after a conflict with oil workers whose dog mauled his reindeer, Sergey Kechimov was sentenced by a local court for threatening oil workers.

In those days, indigenous communities, independent media, human rights and environmental organizations were able to create a powerful public campaign to protect Kechimov’s rights as a victim of authorities and the oil industry on national[36] and international[37] levels. Even though Sergey was finally sentenced, the sentence was relatively painless – 30 hours of communal work only.

But in December 2022, he was sentenced[38] again for threatening oil workers with already six months of liberty restriction, and immediately after the court, he was again arrested by the local police, which brought an accusation against him for police disobedience.

Today the investigation against him continues, and nobody from human rights organizations or independent media can support him as there are no remaining such organizations in the region now. In 2022 Sergey Kechimov didn’t receive any legal support or media attention, as well as support from his own community. While some local indigenous organizations serve[39] the interests of the regional authorities and oil companies, others are intimidated by the recent strengthening[40] of the repressive Russian legislation and can not support Sergey Kechimov in his fight.

Intimidation of indigenous critique voices

Indigenous activists and indigenous rights defenders also didn’t avoid prosecution from authorities.

In February 2022, the next day after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Chukchi student Mark Zdor who studied at the St. Petersburg University named after AI Herzen, was arrested[41] by the police after he, with his classmates, participated in the antiwar protest action in St. Petersburg. Mark was fined to 10 thousand rubles. Several days later, after the police came to his house to continue the investigation, he left Russia, fearing for his safety.

In May 2022, an indigenous activist from Pevek (Chukotka region), Igor Ranav, was fined[42] for his antiwar position (the exact perpetration was the phrase “Yes to the peace! No to the War!” / “Миру — Мир, нет, Войне!”), which he published on one of the social networks).

Several days later, the other indigenous activist from Nenets okrug Konstantin Ledkov has also been fined[43] for the second time for the phrase “Crimea belongs to Ukraine” / “Крым это Украина”.

In July 2022, during the session of the UN Expert Mechanism on the rights of indigenous peoples in Geneva, a representative of Shor peoples, Yana Tannagasheva, made a presentation on violations of the indigenous peoples’ rights by coal companies in the Kemerovo region. After the presentation, Ms. Tannagasheva was approached by a Russian diplomat, who acted in an intimidating manner by asking for her name, phone number and her business card in a reportedly aggressive way. Numerous delegates of the session, including representatives of indigenous peoples, NGOs, and the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, witnessed[44] this incident. The same Russian diplomat later approached the Secretariat of the EMRIP session, asking for information about the list of speakers, including the speakers’ names and the organizations they represent.

Later during the session, several states and indigenous delegations made statements condemning the inappropriate behavior of the Russian state representative just in the UN building.

Fortunately, Yana Tannagasheva received[45] political asylum today in Sweden, where she had been forced to escape from Russia after years of intimidation by authorities and coal companies. She is safe now and does not fear threats from the Russian side. But according to her, the Russian diplomat who threatened her during the EMRIP session didn’t know that fact as he supposed she continued to live in her village in the Kemerovo region. In this light, the attempt to intimidate the delegate and receive personal data could definitely be considered a severe threat to any indigenous activists who continue to live in Russia and trying to inform international human rights bodies about violations of their indigenous rights.