Casual racism in Russia’s everyday life: ‘Even though you are Buryat, you are still one of us’

The Buryats, an ethnic group of Mongolic descent, originate from southeastern Siberia. They represent one of the two predominant indigenous populations in Siberia, along with Yakuts. Today, most Buryats reside in their titular homeland, the Republic of Buryatia. This federally administrated province of Russia extends along the southern shoreline and partially encompasses Lake Baikal. The region, along with many other remote poor regions of Russia, had been disproportionally targeted by the military draft in the Russian war on Ukraine.

Since the beginning of the conflict in Donbas, a meme has emerged about “boevoy Buryat” (“battle-ready Buryats”) prepared to sacrifice themselves for Putin. This meme gained widespread popularity after the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. This has exposed a disturbing undercurrent of racism in a country that swears to be ‘fighting against Nazis. The conflict has also disproportionately highlighted Asians as the face of the war, even though they represent an absolute minority in terms of percentage actively participating. Together with an anonymous volunteer from a charitable foundation and Purbe Dambiev, an activist from the Buryat Center in Mongolia, we are talking about some discriminating phrases against the Buryat community.

‘I thought you could only herd cattle’ or ‘Wow, you can do that?’

These derogatory expressions are based on stereotypes about the low intelligence or qualifications of Asians in Russia. While it may seem that such comments are no longer prevalent, real-life experiences prove otherwise.

A volunteer recalled an incident when she and her friend attended a networking event in Moscow. “When I introduced myself and mentioned that I work as a lawyer, one man was surprised and said, ‘Can you do that?’ In his opinion, all Asians living in cities either work as cleaners or couriers. Then he added, ‘I thought you could only herd cattle.’”

There was another example when a Buryat woman went to a restaurant with her colleagues during lunch. “As soon as I entered the restroom, a woman started questioning me: ‘Where are the paper towels?’ In her view, because I am Asian, I must be only a cleaner at that restaurant,” the volunteer recounted.

‘Buryats are superstitious’

In every nation exists a system of widely accepted norms and values, including myths and superstitions. Superstitions reflect the centuries-long history of peoples, but it is not accurate to speak of Buryats as having a unified collective consciousness. Activist Purbe Dambiev explains, “There are quite a number of Buryats: several hundred thousand in Buryatia, thousands of Mongolian and Chinese Buryats. They are all very diverse, and their local customs vary. Among us, there are people who hold traditions dear, and there are those for whom they are not so important.”

‘Battle-ready Buryats’

Buryats are regular people who, in their daily lives, are not fundamentally different from other nationalities. Describing an entire nation as quarrelsome and aggressive is a clear exaggeration and falsehood. Furthermore, as per Dambiev’s words, the phrase “battle-ready Buryats” is deeply offensive because it characterizes people as if they were some kind of particular breed of dogs.

‘For a Buryat person, you are quite…’ (beautiful, tall, muscular, and so on)

Such comments are common instances of racism that Buryats frequently face when they move to western regions of Russia for education or employment. Those who make such comments assume, for instance, that individuals of a specific nationality or ethnic group are typically not considered attractive, and, in this particular case, beauty is something unexpected and unusual.

A volunteer shares: “The sizes and heights of people depend on numerous factors and can vary even within a single ethnic group. However, such expressions are prevalent even among Buryats themselves.”

Sometimes, the speakers claim that they intended to give a compliment. Nevertheless, these statements should not be mistaken for compliments.

‘Before joining Russia, the Buryats didn’t even have a written language’

This statement is factually incorrect. The Buryats had their own methods of transmitting knowledge and cultural heritage prior to contact with the Russian Empire. The Buryats had a Mongolic vertical script. So such a statement is disrespectful towards Buryat culture and history.

‘Even though you are Buryat, you are still one of us’

This is a highly popular and completely racist statement that categorizes people into specific groups. Furthermore, such expressions are now extremely widespread and even find reflection in popular culture. For instance, in the verses of so-called Z-poets who propagate the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

‘Ni hao’

In western regions of Russia, people might use this Chinese greeting towards any Asian, considering it a funny joke. However, it’s a stereotypical and offensive expression that implies that all Asians are the same, sharing the same culture and language.

‘Did you buy a passport? Is Buryatia also part of Russia?’

It’s not a crime to have a limited knowledge of geography. However, while migrants in Russia are legally required to know the language and culture, not all Russians are aware of which regions are part of Russia. This phrase also symbolizes a division between the “real people” with the right documents and the rest with the wrong ones.

‘Slant-eyed’

There exist several offensive and discriminatory stereotypes associated with the shape of one’s eyes. These physical characteristics lead to derogatory characterizations: Buryats are often unfairly portrayed as less intelligent, more cunning, or having hidden motives.

“The belief that one’s eye shape can somehow reveal their character, behavior, or intelligence is absurd. Such oversimplified perceptions of appearance dismiss the rich history and cultural diversity,” notes a volunteer.

She adds that the complex of “slant eyes” did not emerge out of thin air. Some Asians attempt to address it by undergoing a “European eye fold” surgery. “These operations are quite popular, not only in Russia’s national republics but also in Kazakhstan,” she further explains.

On one hand, stereotypes are a fairly common aspect of intercultural relations. People with a sense of humor may identify traits associated with specific groups. However, there is a downside to this process: hurtful stereotypes can narrow the boundaries of the world, create actual barriers between people, and fuel division and animosity. Stereotypes about Buryats are a vivid example of these negative social processes.

Russia: Europe imports €13 billion of ‘critical’ metals in sanctions blindspot

Despite a raft of sanctions now in place against Moscow, the critical raw materials trade remains exempt and EU purchases persist. Investigate Europe analysis finds European companies continue to pour billions into mining firms linked to the Kremlin.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the 27 EU countries have adopted 11 sanction packages, targeting raw materials including oil, coal, steel and timber. But minerals that the EU considers as “critical” raw materials – 34 in total – still flow freely from Russia to Europe in vast quantities, providing crucial funds to state enterprises and oligarch-owned businesses.

While some of its western allies have targeted Russia’s mining sector – the UK recently banned Russian copper, aluminium and nickel – the EU has continued its imports. Airbus and other European companies are still buying titanium, nickel, and other commodities from firms close to the Kremlin more than a year after the invasion, Investigate Europe can reveal.

Between March 2022 and July this year, Europe imported €13.7 billion worth of critical raw materials from Russia, data from Eurostat and the EU’s Joint Research Centre shows. More than €3.7 billion arrived between January and July 2023, including €1.2 billion of nickel. The European Policy Centre estimates that up to 90 per cent of some types of nickel used in Europe comes from Russian suppliers.

“Why are critical raw materials not banned? Because they are critical, right. Let’s be honest,” the EU’s special envoy for sanctions, David O’Sullivan, pithily said at a September conference.

The Union is desperate for critical raw materials to achieve its aim of climate neutrality by 2050. These commodities are crucial for electronics, solar panels and electric cars, but also for traditional industries like aerospace and defence. Yet they are all too often in scarce supply, unevenly available across the globe, and in high demand.

“The war in Ukraine has clearly shown the willingness of Russia to weaponise the supply of key resources. As Europeans, we cannot tolerate that,” says Henrike Hahn, a German Green MEP working on the new Critical Raw Materials Act.

Europe’s imports not only fund Russia’s war economy, but also benefit Kremlin-backed oligarchs and state companies. Although the EU has targeted some shareholders, Russia’s mining businesses have faced no restrictions. The loophole is even more glaring that the US and the UK sanctioned several firms directly, further isolating the EU in its double standards.

Analysis of Russian customs data shows that Vsmpo-Avisma, the world’s largest titanium producer, sold at least $308 million of titanium into the EU via its German and UK branches between February 2022 and July 2023. It is part-owned by Russia’s national defence conglomerate, Rostec. The two companies share the same chairman: Sergei Chemezov, a close Putin ally. The pair were KGB officers in East Germany in the 1980s.

Both Chemezov and Rostec are under EU sanctions and helped supply tanks and weapons to the Russian army. Brussels has not sanctioned Vsmpo-Avisma directly, but the US did ban exports to the firm on 27 September, saying it was “directly involved in producing and manufacturing titanium and metal products for the Russian military and security services.”

Among Vsmpo-Avisma’s largest European customers is Airbus, the aerospace giant partly owned by the French, German and Spanish states. Between the start of the war and March 2023, Airbus imported at least $22.8 million worth of titanium from Russia; a fourfold increase in value and tonnes compared to the previous 13 months.

From 14 March 2023, Vsmpo-Avisma stopped identifying buyers in customs filings but nothing indicates a significant change in trends. Titanium imports to France only slightly decreased between then and July 2023, and Airbus still listed the company as a supplier in July.

“We have no comment on the details and evolution of our titanium sourcing volumes,” an Airbus spokesperson said. “Generally speaking, Airbus is currently ramping up commercial aircraft production and this is having a mechanical impact on its overall procurement volumes.” Even though it will take time, the group is reducing its dependency on Russia, the spokesperson said, adding that a ban on Russian titanium for civil aviation would “encourage the Russian industry to focus on defence needs.”

Unlike Vsmpo-Avisma, other Russian companies have avoided naming their buyers in customs filings altogether. Yet the data still gives a scale of their fruitful relationship with the west. Nornickel, the world leader in palladium and high-grade nickel, exported $7.6 billion worth of nickel and copper into the EU via Finnish and Swiss subsidiaries between the start of the war and July 2023. It also sent over $3 billion of palladium, platinum and rhodium into Zurich airport. In 2022, almost 50 per cent of Nornickel’s sales went to Europe. Brussels has not sanctioned the group nor its chairman and largest shareholder, Vladimir Potanin, an oligarch and former deputy prime minister under US and UK sanctions.

Aluminium giant Rusal also uses tax havens to funnel minerals to Europe, where it owns the EU’s largest alumina refinery in Ireland and a smelter in Sweden. Its Jersey and Swiss-based trading houses brought at least $2.6 billion of aluminium into the bloc in the 16 months following the invasion of Ukraine. In August 2023, Rusal said Europe still accounted for a third of its revenues. Rusal’s main shareholder is oligarch Oleg Deripaska, sanctioned by the EU and its western partners.

Anti-corruption NGO Transparency International says it does not make sense that the sector has avoided sanctions given the known links. “They are part of the system and fueling Putin’s war,” says senior policy officer Roland Papp. “So it’s perfectly logical to ban those critical raw materials from Russia, as we did for other sectors and goods.”

Since the start of the war, other European buyers of Russian metals have included Germany’s GGP Metal Powder ($66 million of copper), French arms-maker Safran ($25 million of titanium) and Greece’s Elval Halcor ($13 million of aluminium). Dutch logistics firm C. Steinweg also handled at least $100 million of various critical metals on behalf of its customers.

Safran confirmed they are still buying titanium from Vsmpo-Avismo but are working to reduce their Russia purchases. GGP Metal Powder said “there is no real alternative to our supplier from Russia”. C. Steinweg said they follow all rules and sanctions. Elval Halcor, Vsmpo-Avisma, Rusal and Nornickel did not reply to requests for comment.

— Roland Papp, Transparency International

“We’ve increased our dependence on Russia. It was an absolute and serious mistake.”

At the start of the war, Europe was relying on Russian producers for 30 per cent of its nickel, 35 per cent of its alumina and 15 per cent of its aluminium, according to an internal memo by trade body Eurometaux seen by IE. Russia accounted for 41 per cent of the world’s palladium production, and up to 25 per cent of its vanadium output.

“Russia occupies a large part of Eurasia – it possesses a big part of the strategic reserves of critical raw materials, on par with China,” says Oleg Savytskyi from Razom We Stand, a Ukrainian NGO. Moreover, “the low density of the population, authoritarian control and practical absence of environmental and human rights protections made investments in the mining of Russia’s resources terribly attractive,” he adds.

The EU’s crippling dependency should have been curbed earlier, argues Transparency International’s Papp. “We’ve had enough time to react. The annexation of Crimea dates back to 2014, the invasion of Georgia even dates back to 2008 15 years ago! And what have we done? We’ve increased our dependence on Russia. It was an absolute and serious mistake.”

A Polish diplomat said Poland has pressed the EU to “decouple completely” from Russia in several areas, “but for the sake of unity and efficiency in adopting new sanctions packages we have agreed to postpone particular measures until further discussion.”

As EU sanctions require unanimity among all member states, divergent national economic interests can often water down packages. When the ninth set of sanctions banned fresh investments in Russia’s mining sector in December 2022, it included an exemption to invest in some mining activities for some critical raw materials. As a result, European companies can still pour cash into Russian mines to extract nickel, titanium and other key metals.

Nickel was the most imported critical raw material since the start of the invasion of Ukraine

The European Policy Centre estimates that up to 90 per cent of some types of nickel used in Europe comes from Russian suppliers.

EU imports of selected raw materials, March 2022 – July 2023, in billion euros.

Sources: Eurostat and EU’s Joint Research Centre

The European Commission won’t publicly comment on whether or not it has proposed a ban on critical raw materials. One reason could be that “sanctions are carefully designed to hit their targets while preserving EU interests,“ an EU source told IE.

Weaning the EU off Russia’s critical and strategic materials will be difficult. Replacing suppliers and forging new international partnerships is an arduous process. Finding a raw material, such as titanium or copper, with a similar quality and price of those from Russia is also a challenge.

Imposing tariffs or severing ties too quickly could lead to a global price surge which would harm European buyers while benefiting Moscow. A ban could also prompt India, Iran, and China to intensify purchases, further depleting critical raw material resources for EU industries.

Tymofiy Mylovanov, president of the Kyiv School of Economics, says a ban would be difficult to implement given global demand challenges and Europe’s reliance on Russia. “Overall, with these specific materials, the monetary value of what Russia would lose from the EU import ban, might be smaller than the effect on the EU production,” says Ukraine’s former trade and economic development minister.

UN trading data shows that while EU imports of Russian copper, nickel and aluminium imports have declined in the past two years, nickel and aluminium revenues remained stable. Russia’s nickel sales to the EU were worth $1 billion in the first half of 2021 and were $1.1 billion two years later.

The Union is now trying to reduce its dependency. In March, the European Commission presented its Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), a new legislation aimed at reducing EU dependency on third countries for critical raw materials.

“War in Europe is a risk which was not present in the last decades and Russia was known as a reliable supplier,” says German MEP Hildegard Bentele, shadow rapporteur on the CRMA at the European Parliament. “The EU should take immediate action to support European companies to decrease and replace their CRM deliveries from Russia as soon as possible.”

The High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy is expected to propose a 12th package of sanctions in the coming weeks, which will be then discussed by member states. Brussels hopes the package will renew pressure on the Russian economy and sap its fighting strength on the battlefields of Ukraine. Restrictions on critical raw materials does not seem to be on the table.

Editor: Chris Matthews

Graphics: Marta Portocarrero

This investigation is supported by Journalismfund Europe’s Investigation Grants for Environmental Journalism.

Looking for Indigenous Stories at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference

By Dev Kumar Sunuwar (Koĩts-Sunuwar, CS Staff)

I felt anxious and overwhelmed walking into the 13th Global Investigative Journalism Conference, which took place on September 19-22, 2023 in Gothenburg, Sweden, since, for the past 20 years, I have been working in a small, Indigenous-led media outlet focused on the tiny spheres of Indigenous Peoples’ lands and territories in Nepal, usually only equipped with a voice recorder or mini-camera along with a pen and diary to tell stories of Indigenous Peoples’ issues and rights violations.

This year’s Global Investigative Journalism Conference was attended by 2,138 investigative journalists, reporters, and editors from 132 countries, making it the largest gathering of investigative journalists in history. The conference focused on practical and advanced reporting training including the latest tools and techniques, extensive networking, and brainstorming sessions, with over 200 sessions. The Indigenous Journalists Association, together with the Global Investigative Journalism Network, brought Indigenous journalists to be part of the conference. Still, there were only 15 Indigenous journalists in attendance, from Taiwan, Nepal, Canada, the U.S., New Zealand, Finland, Guatemala, and Colombia.

Despite the different geographies and cultures represented at the gatherings, the similarities in the impacts of racism, colonization, land grabbing, and forced displacement of Indigenous Peoples, among others, weaved together all of our stories. The coverage of such violations is extremely limited. If Indigenous Peoples’ issues or rights violations are covered at all, they are not always properly or positively portrayed. The panel, “Investigating Indigenous Stories,” discussed the importance of Indigenous stories and the time needed to create them, which is not understood by many newsrooms.

Brittany Guyot (Northlands Dënesųłiné First Nation), an investigative reporter with APTN Investigates in Canada, said on the panel, “In Canada, Indigenous people are far more likely to go missing or be murdered compared to the non-Indigenous populations. In the last three months alone, there have been approximately three women whose remains have been found in local landfills. The issue that we’re having now is recovering their remains and returning them to their families so that they can have proper ceremonies. If it were a non-Indigenous person whose remains were found in a dump or [the] garbage, the government would make every effort to recover those people.”

Guyot, who has long been reporting on the deaths of Indigenous children at residential schools, as well as the overrepresentation of Indigenous people in the criminal justice system, reflected on the bitter reality of these stories being ignored by the mainstream media: “Such issues have not been in a national conversation nor covered well enough by the media. I think it’s incredibly important that we have Indigenous journalists at the decision-making level of the newsroom to be able to tell these stories. Sadly, we don’t have adequate [numbers of] Indigenous journalists in Canada, especially Indigenous women, who are in investigative journalism. We need more Indigenous investigative journalists who can tell such sensitive stories best,” she said.

Panelists concurred that more Indigenous journalists in newsrooms would create better representation and serve the needs of society. Historically, the media coverage of Indigenous Peoples has tended to focus on the negative and is dominated by non-Indigenous voices. Therefore, strong voices are needed in favor of decolonizing and Indigenizing the media to better reflect Indigenous voices.

“In the U.S., there are several things that impact Indigenous Peoples—economy, land grabbing, health care—[that] receive little or no coverage in the media, primarily because reporters don’t find those stories particularly important. And there are no signs of such an attitude going away anytime soon. A few places have started Indigenous affairs desks to deal with this problem, but most of them are at small nonprofit outlets or public radio stations. We don’t see this at large organizations or mainstream organizations,” said Tristan Ahtone (Kiowa), editor at large at Grist. “I believe the easiest thing to do is hire Indigenous journalists to work in your newsroom. But if you can’t hire an Indigenous journalist, you can collaborate and work with other Indigenous reporters at other news outlets. There are many, many ways that you can safeguard your work, safeguard your journalism, and make sure that you’re doing the best work possible,” Ahtone said.

Investigative journalism is not simply about making hidden facts or secrets public. It should also focus on social justice and accountability and aim to right the wrongs and protect the most vulnerable groups of society, making those in power accountable to them. But lately, investigations have been primarily focused on covering crime and corruption. Most media is controlled by the power, money, and stories of the dominant group of society.

Even so, Indigenous journalism is on the rise. Indigenous journalists and Indigenous media outlets are leading the way in telling our stories and increasingly demonstrating to the non-Indigenous media how this coverage can and should be done in response to centuries of inadequate reporting, systemic misinformation about Indigenous communities, and a dearth of coverage that perpetuates Indigenous Peoples’ invisibility.

“We need more journalists and more media organizations who can listen to Mother Earth and storytellers who pay attention to the issues affecting Indigenous Peoples and consider Mother Earth a character who feels what is happening and has something to tell,” said Vanessa Teteye Mendoza, (Bora-Uitoto) from La Chorrera, Amazonas, Colombia, from the Iñeje (Canangucho) clan. Mendoza works at the independent intercultural media agency Agenda Propia, where she has reported on and served as an editorial advisor for various stories, especially on the struggles and realities of Amazonian Peoples.

In Scandinavian countries, the mainstream media has given scant attention to covering the stories of reindeer herders, the Sami Peoples living in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. “The climate crisis has already resulted in consequences on our livelihoods, and our lives. The extractive industries, electrification, and industrialization have caused devastating impacts. Sami people are also struggling to keep up their language and culture. There has been an increasing threat to the safeguarding of lands. The mineral and mining industries are booming on lands that the Sami people have been inhabiting for generations without the free prior and informed consent of the Sami people but are hardly covered by the mainstream news,” said Maria Sayet (Sami), executive producer at Sameradion and SVT Sapmi in Kiruna, Sweden.

“Coming from Sami society and knowing the problems that Sapmi, or the reindeer herders, have been facing, we should not be the only ones reporting on how Indigenous Peoples are struggling or fighting and surviving, in my opinion. It is also the mainstream media that has to take responsibility for covering Indigenous stories and their problems because Sami people are also part of the bigger communities, part of the countries, a part of the world population,” Sayet said.

In Japan, recognized Ainu Indigenous Peoples have not been able to hunt deer, fish for salmon, or practice their culture and rituals in the rivers or forests near where they live. In the Philippines, Kankanaey-Igorot Indigenous Peoples in the Cordillera Region have been struggling against the injustices of large-scale corporate gold mining for more than a century. In Malaysia, India, and Nepal, Indigenous Peoples are facing constant threats and have been struggling as their customary land, territories, and forests are transformed into protected areas or the rivers that they have collectively stewarded for generations have become hubs for hydro dams. But these issues are rarely covered in the news.

Associate Director of IJA, Francine Compton (Sandy Bay Ojibway First Nation), summarized the feeling of Indigenous journalists attending the conference: “The mainstream media does not report accurately on Indigenous issues. Therefore, the work of Indigenous investigative journalism in Indigenous issues is needed more than ever, as their freedom of information is getting worse than ever.”

Non-Russian Anti-War Movement Abroad Expands into Center for Support of National Languages and Cultures

Putin’s war in Ukraine has triggered the growth of nationalism in many non-Russian groups inside his country, but one of the broadest and most dramatic examples of this is abroad in London’s Yurt Community which began as an anti-war movement but has now expanded to be a center for the promotion of non-Russian languages and cultures.

Lidiya Grigoryeva, an activist with the group, says the Yurt Community movement was launched a year ago in London to help non-Russians from the Russian Federation express their opposition to Putin’s war in Ukraine. That has led the group to work to promote the salvation and growth of their nations (idelreal.org/a/32577459.html).

Last month, she says, the group launched a Navigator of the Languages of the Indigenous Peoples of Russia, an internet project (t.me/yurt_community/38 and yurtcommunity.org/ru)that is “the only platform for the preservation and dissemination of academic and other materials on the languages of ethnic groups living on the territory of Russia.”

Grigoryeva herself is a Yakut who spoke her national language at home but lost the habit of doing so when she went to a Russian-language school. She recovered her interest in her national language when she studied in St. Petersburg and was subjected to bullying by Russians for using her language. Instead of repressing her, such experiences revived her interest in Sakha.

In her republic, she says, there is a general revival of interest in the Sakha language. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the situation among the numerically smaller peoples of the Russian north. There the rising generation rarely knows the national language, and these tongues face extinction in the near future. The Yurt Platform is designed to combat that.

Unfortunately, she continues, this is a difficult but absolutely necessary struggle: “The trend in modern society is toward simplification, seeing everything in black and white,” with people saying there’s no need for learning any languages except Russian and English. But “that is the same as saying we don’t need thousands of kinds of plants or more than seven colors.”

“Diversity of languages and cultures only enriches any society,” Grigoryeva says; “and it is very sad to realize that we are losing this wealth.” Of course, to reverse the current path requires more than instruction in these languages; it requires a wholesale revamping of society so that people will find the use of these languages useful to themselves.

According to the activist, “a language lives in a milieu – and few are interested in studying a language which does not help them find work or get a high-quality education, especially if one considers the large number of stereotypes and stigmas about indigenous languages.”

Activism in support of languages is thus connected with activism in support of nations more generally, she argues. “There exists a great diversity of ethnic activism, and the study of the culture, history and language of one’s people is not necessarily connected with national liberation ideas.” But they can support one another.

“For us,” she says, “de-colonization is in the first instance a return to ourselves of our cultural identity, a sense that we rank too as ‘a state-forming people,’ no better and no worse than others, are capable of resisted forced russification, and struggle for our right to be ourselves” rather than to be defined by others.

According to Grigoryeva, “our movement includes representatives of civil society … [because] each people and each individual has the right to a worthy life, respect for his or her culture and language. We must not be ashamed of our identities, cultures, and langauges, just as we must not discriminate against others on ethnic grounds.”

“The problem of Russia is that instead of a real discussion and resolution of problems … the authorities hypocritically speak about ‘the friendship of the peoples’ and create a beautiful picture for show while deepening the contradictions in the current system. Therefore, the popularity of national liberation movements and de-colonial discourse will only grow.”

“Our movement,” Grigoryeva says, “does not form a political unit; but we understand that in a democratic country, national-liberation movements could become one of the parties in republic parliaments.” Today, the situation in Russia is far from that; but it is a goal worth working towards.

Enabling a just energy transition: The crucial role of corporate accountability in the EU Critical Raw Materials Act

The European Parliament is preparing to vote on the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) this week, providing a golden opportunity to embed key principles which will promote a true just energy transition.

Climate change presents a profound risk to human rights. Responding to it with the urgency it deserves requires changing unsustainable patterns of consumption and production and a shift to renewable sources of energies – such as wind and solar. Yet, acceleration in the extraction of raw materials needed to manufacture these technologies risks exacerbating human rights violations and environmental destruction that have long been the hallmarks of the extractive sector. Repeating its failure to prevent harmful impacts on affected communities is not an option. More than half of global resources for minerals essential in the energy transition are located on or near the lands of Indigenous and peasant peoples – whose rights to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) must be preserved.

Mining comes with risks of human rights abuses. Between 2010 and 2022, the Resource Centre documented 510 allegations of abuses in connection with the extraction of copper, cobalt, lithium, nickel, manganese and zinc. Civil society organisations and Indigenous Peoples’ movements have called for the EU to safeguard human rights and the environment in the CRMA. Without adequate human rights and environmental protections, and without questioning European consumption levels for virgin raw materials, incentivising the intensification of mining activities can lead to a dramatic increase of their impacts on local communities, Indigenous Peoples and their environments.

The European Union (EU) has an opportunity to lead a rapid, global energy transition which leaves no one behind, addressing the climate crisis whilst respecting the rights of communities, human rights and environmental rights defenders and Indigenous Peoples, and guaranteeing certainty and competitiveness for companies and investors.

1. Aligning corporate responsibility and demands on companies:

The CRMA should guarantee policy coherence and legal certainty through explicit reference to international due diligence standards set out in the UN Guiding Principles on Business & Human Rights (UNGPs), the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the upcoming Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) – and ensure they apply to all strategic project promoters in the CRMA. This involves requirements for substantive human rights and environmental due diligence (HREDD), to avoid sole reliance on industry-led certification schemes – whose limitations, amongst others, resulting from a lack of transparency, independence and conflicts of interest have been documented. Such schemes promote top-down approaches to compliance and stifle innovation and ongoing improvements in corporate due diligence practices. While certification can support compliance with sustainability or corporate HREDD responsibilities, it cannot achieve these by itself.

2. Corporate accountability and respect for human rights and Indigenous Peoples’ rights:

Legislation on raw materials supply chains also needs to tackle the environmental and social impacts of mining for transition minerals. These are multifaceted and, as research by the Resource Centre has shown, are often associated with multiple harms including air, soil and water pollution, overuse of water resources, loss of biodiversity and deforestation, health and safety issues in the workplace, land rights abuses and lack of consultation and engagement with local and Indigenous communities. The current global rush to mine for more transition minerals also creates incentives for unscrupulous mining companies to use corrupt practices to cut corners on environmental and human rights safeguards, as well as expedite community consultation processes. Mining is also the most dangerous sector for human rights defenders.

Corporate abuse, and the distrust it generates, risks derailing the global energy transition. EU policymakers must consider the track record of human rights and environmental abuses of candidate project promoters. Fast-tracking mining projects cannot come at the expense of human rights, and especially not Indigenous Peoples’ rights. Respect for their unique and internationally recognised rights, in particular their right to self-determination, which includes the right to give or withhold their FPIC to projects on their lands, must be front and centre within the CRMA.

To ensure sponsored projects are grounded in meaningful involvement and respect for public participation rights of local communities is anchored in international law, language such as ‘facilitating public acceptance’ must be avoided. Engagement with local communities should be defined in the framework of existing international obligations, including Article 27 of the International Convention of Civil and Political Rights, the UNGPs, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, as well as the International Labour Organization’s Convention 169.

3. Enabling a global just transition

The CRMA should include safeguards to enable resource-rich countries’ self-determined development, energy security and local value addition, and guarantee the availability of such materials for the energy transition requirements of non-EU countries and prevent human rights violations. It is equally important for the CRMA to adopt a systemic approach to the determination and long-term reduction of environmental footprints. Taking proactive measures to mitigate the increase in demand of critical raw materials should be a core strategy of the EU to strengthen its strategic autonomy and reduce its global environmental footprint.

Enabling a global just transition must also include a strong participation of civil society in the governance body of the CRMA. Civil society’s meaningful participation, including organisations from partner countries, is also essential when selecting and prioritising strategic partnerships.

By Olga Martin-Ortega and Caroline Avan, Business & Human Rights Resource Centre

Johanna Sydow, Heinrich Böll Foundation

Alejandro Gonzalez and Joseph Wilde-Ramsing, SOMO

What Decolonization Means for Russia’s Indigenous Peoples

For the indigenous peoples of Russia, decolonizing the country is not just a matter of historical justice. In our eyes, it is a necessary precondition for moving past the obsolete narratives that the Russian state and society tell themselves; narratives that are founded in widespread misunderstandings of history, official propaganda, and outright lies.

In Russian historical narratives, the colonization of Siberia and the Far East is described as a “unification,” as in “voluntary unification.” Historians point to the relatively peaceful nature of Russia’s eastward expansion, which they call the Cossack “March to Meet the Sun,” in contrast to the brutal campaigns of Cortez in the lands of the Aztecs.

This whitewashing of history takes place at many levels. For example, in the late 1990s, Russia planned to celebrate the anniversary of the “voluntary unification” of Kamchatka and Russia. However, the Tkhansom, the council of the Itelmen peoples who are native to Kamchatka, took a formal decision to boycott the celebrations, on the grounds that the annexation of Kamchatka could in no way be described as voluntary. Instead, it was the violent conquest of the peninsula by the Russian Empire.

When pressed at a 1997 academic conference in Kamchatka, Russian historians were unable to provide sufficient arguments in support of the myth of the region’s “voluntary unification with imperial Russia.” When it became clear just how tenuous their arguments were, one academic remarked, “Alright, so there was colonization, but it was good colonization.” The participants of the conference were then left to guess what distinguishes “good colonization” from the usual kind.

In reality, as the testimony of numerous witnesses shows, the armed conflicts between the Russian state and the subjugated peoples of Siberia demonstrate that Russian colonization differs little from European colonialism in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The only apparent difference was how the colonizers treated the people they conquered. While the Spanish Conquistadors committed large-scale massacres in their pursuit of gold, the Siberian Cossacks were more interested in extracting lucrative tributes from locals. These tributes, paid in the form of furs collected by the legendary hunters of the conquered peoples, became a major source of wealth for the tsars. The legend that indigenous peoples were such expert hunters they could “shoot a squirrel in the eye” persists to this day.

For the Indigenous peoples of Russia, it is vitally important that the Russian state and society recognize the historical fact of colonization. This could become the jumping-off point for a new, more just relationship between Indigenous peoples and the state. Such recognition is the first step toward the kind of national reconciliation that took place in Canada, Norway, Australia, and other countries with a history of injustice toward their indigenous peoples.

Moreover, acknowledging colonization as a process and the undeniable legacy of the Russian Empire and its successor states could be the starting point for the construction of a new state, one that dispenses with revisionist history in favor of historical truth.

This would go a long way toward dismantling the particularly toxic myth of the God-given role of the Russian people in world history, and the special path of a Russia that acts as a lone bulwark of traditional values against a West that is mired in iniquity. It will be a great boon to Russian society when this perverse conception of patriotism is allowed to implode. It has been relentlessly amplified for decades by the powerful state propaganda machine in the service of Putin’s criminal régime, and the wars of aggression against Russia’s neighbors.

The Russian people must finally recognize that, by and large, they are no different from other European countries. There is just one exception: the Russians’ ancestors lived on the eastern frontiers of Europe, beyond which lived numerous indigenous peoples of Siberia. Those territories were only conquered thanks to military technologies that the Russians received from their European neighbors (facilitating its growth into a geographic giant, a source of continuing pride for modern-day Russians). Other European countries lacked vulnerable neighbors, and so had to look overseas for their expansionist aims.

As the right of peoples to self-determination gained acceptance in the latter half of 20th century, culminating in its enshrinement in the United Nations Charter and then the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, the overseas colonies of the European powers, one after another, started to gain their independence.

Meanwhile, Soviet leaders — who were happy to invoke those arguments when it suited them — liked to pretend that the Soviet Union itself was exempt from these principles.

Those peoples who had the dubious privilege of finding themselves within the U.S.S.R. were kept busy building socialism. They would not have dreamed of demanding their independence from the Kremlin. Those that did were swiftly dealt with by the KGB. The Kremlin was happy to use UN declarations to actively promote “anti-imperialist” struggles around the world, but this didn’t extend to how it treated its own people.

Today, a multitude of societal and political players are actively discussing the country’s post-Putin political future. Their proposals range from an even greater role of the state and its repressive apparatus to the creation of a parliamentary republic, and include the suggestion that Russia be divided into seperate independent ethno-states.

This is not the place to go into the details of these various scenarios. Self-determination for the peoples living on the territory of the Russian Federation today is of course to be welcomed, as a matter of principle. However, there are two issues that should be a source of concern.

The first is raised by representatives of the Russian opposition who consider creating new states on the territory of the Federation to be either entirely unfeasible, or a proposition with marginal support in the ethnic republics.

The opposition is debating this vital question without consulting any representatives of the colonized peoples themselves. This demonstrates the pervasiveness of the imperial mindset even among people of seemingly impeccably liberal credentials, and not just members of Putin’s entourage.

It is worth asking what would happen if these opposition politicians came to power and found themselves in a situation where the majority of Chechens or Buryats pronounced themselves in favor of independence from Russia. Would they go to war to reassert control? Past experience is not encouraging.

A second issue that should be a cause for alarm is the rhetoric of some ethnic national activists themselves. There have been calls from such figures for the dismantlement of Russia and the creation of separate ethnic states without giving sufficient thought towards what these new states will look like. Nor do they propose a mechanism for handling the dissolution. It is as though the only thing that matters is their separation from Russia.

The sad legacy of democracy-building efforts in the former Soviet republics of Central Asia should make them more cautious about the disintegration of the Russian Federation. The expectation that it will lead to a useful and favorable outcome for the peoples living on these territories and for the world as a whole should not be taken for granted.

We suspect that many representatives of the Sakha people of Yakutia, for example, would be aghast at the prospect that one day they might be liberated from Russia’s authoritarian regime only to find themselves citizens of a new country styled after “democratic, law-based, secular” Turkmenistan. Despite boasting in its constitution that “the people are the only source of state power,” the country is often compared to North Korea. Independence risks trading one authoritarian regime for another.

There will be no easy solutions to the political, legal, technological and military problems and risks that any new state entities will have to face. Where is the guarantee that the republic of Sakha will end up led by enlightened, liberal, pro-Western nationalists rather than its current leader? Aysen Nikolayev is a notorious Putin loyalist. His entourage is rife with corruption and he has centralized control of both enormous financial resources and even the security services. Will he take fright and run after the political death of his patron? Or will he seize the opportunity to re-enter politics under a different guise and assert his personal dominance over the new republic?

The dissolution of the Soviet Union shows that, sadly, the former leaders of the republics, more often than not, are first in line to take up the reins of power. The West may have little inclination to step in. On the contrary, it would in all likelihood lose no time in establishing favorable economic relations, seeing that it is often more expedient to deal with authoritarian regimes than with democratic ones. That is, for as long as the dictator does not completely lose the plot and launch military adventures.

The bitter reality is that there is virtually no prospect that the relatively small populations of the indigenous peoples of Russia’s Far North, of Siberia, and of the Far East will ever have the luxury of achieving self-determination in the form of independent states. Whichever way the political situation in Russia evolves, we are likely to find ourselves living in someone else’s country.

Numerous other problems stand between our peoples and self-determination. We suffer from the absence of qualified specialists, the geographical isolation of our traditional lands, the low level of education of our people, and inadequate financial and administrative resources. Additionally, we are for the most part but a minority of the population in the regions that are our ancestral homes.

For us, a key prerequisite for our survival and continued development as nations in our own right must thus be not a chance to create and govern our own states, but meaningful political participation in Russia. Our institutions of self-government must have the possibility of ensuring that our hunters, fishers, and herders have access to their traditional lands and traditional resources, that our cultures and languages are preserved, and that our peoples have an opportunity to pursue the realization of their political, economic, and social potential on the twin pillars of tradition and new knowledge and technologies.

For us, democracy, the rule of law, and respect for human rights are the basic principles that can help our peoples protect their collective rights for development and self-determination. Faced with an overwhelming power imbalance, the indigenous peoples essentially have no other recourse apart from international law to assert their rights.

This is why we believe that Russian civil society, political players, opposition leaders and ethnic activists should embark on a nationwide debate devoted to the processes of decolonizing Russia. We believe that such a debate can bring together people of diverse views around the same table, where we can begin grappling with our undeniable political differences. It will also look for a shared vision of our future and the future of the country of which we are citizens. The first step is to agree that Russia needs decolonization of its past, present, and future.

Members from several First Nations rally against northern Ontario mining plans

Members of several First Nations rallied outside the Ontario legislature Thursday to raise concerns about mining exploration they say is happening on their lands against their will.

Indigenous leaders and community members said they weren’t consulted as mining prospectors staked claims on their territories. They also pushed back against the province’s plans to expand mining in the mineral-rich Ring of Fire region, about 500 kilometres northeast of Thunder Bay.

“We want our land to stay pure. We are not just doing this for us today, we are doing it for future generations so they will be able to continue to do our traditional practices and way of life,” said Grassy Narrows First Nation Chief Rudy Turtle.

“We are fighting for that.”

In February, four first Nations _ Grassy Narrows, Wapekeka, Neskantaga and Big Trout Lake First Nations _ said they formed an alliance to defend their lands and waters after mining prospectors staked thousands of new claims on their lands over the last few years.

They said they wanted the provincial government to seek their communities’ informed consent before allowing companies to explore the First Nations’ lands for precious minerals.

Muskrat Dam First Nation has since joined that alliance and Turtle, of Grassy Narrows, said he hopes more communities become part of the group.

Grassy Narrows First Nation, located about 100 kilometres northeast of Kenora, Ont., has said it has seen about 4,000 mining claims on its lands since 2018, when the Ontario government allowed any licensed prospector to register a mining claim online for a small fee.

The government’s online mining system does not tell prospectors before they stake a claim whether the land is part of an Indigenous territory.

A government spokesperson said in a statement Thursday that the Supreme Court of Canada “has confirmed that Ontario can authorize development within the Treaty 3 area” in the province subject to satisfaction of its obligations regarding Indigenous Peoples, including the duty to consult.

“We will continue working towards consensus on resource development opportunities by carefully balancing the priorities, needs and concerns of Indigenous communities that exercise Aboriginal or treaty rights in the Northwest, including other Indigenous communities that, like Grassy Narrows, hold rights under Treaty 3,” the spokesperson said.

On Thursday, First Nations members also raised concerns about the province’s development plans in the Ring of Fire, saying they wanted further engagement with the government as they looked to have their land rights safeguarded.

“There hasn’t been any consultation at all and here’s Ontario saying they have legally consulted the community during the pandemic when we couldn’t even meet during the pandemic, we had our community lockdown,” Neskantaga First Nation Chief Chris Moonias said.

Those rallying at the legislature said Thursday that several First Nations groups planned to hold a march in September to reiterate their call for the government to “end unwanted mining activity on their territories.”

The Indigenous affairs minister has previously said the government is focused on building relationships and meets regularly with Indigenous leaders from across the province.

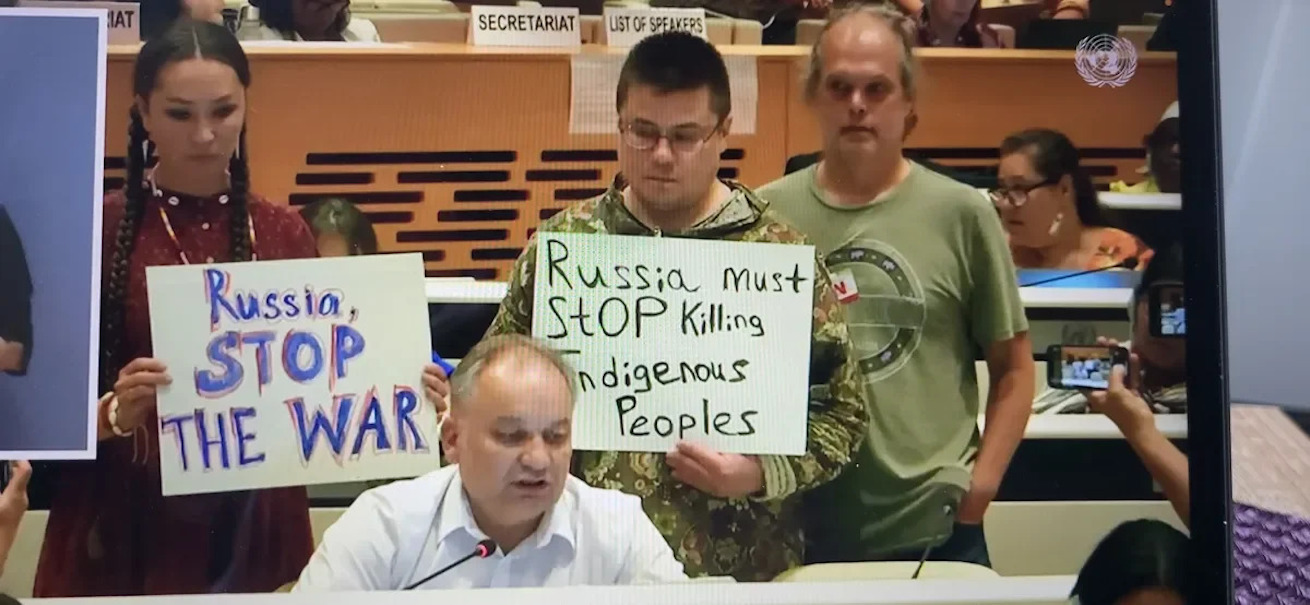

Representatives of Russian Indigenous Peoples hold up anti-war posters during UN session

Representatives of Russian Indigenous Peoples have staged a protest against the war in Ukraine during a session of the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP) — a subsidiary body of the United Nations’ Human Rights Council, their colleague Andrey Danilov shared.

On 17 July, the activists stood up holding posters spelling out anti-war statements during the speech by the representative of the Crimean Tatar Centre, Eskender Bariyev. The posters said “Russia, stop the war” and “Russia must stop killing Indigenous Peoples”.

One of the protesters is Yana Tannagasheva — she told Novaya-Europe that Crimean Tatars and representatives of Indigenous Peoples of Russia which had had to flee the country due to persecution seek to use the UN platform to protect the rights of their people.

In particular, last year they advised the UN Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to study the topic of how militarisation impacts the lives of Indigenous Peoples in Russia.

According to the representatives of Indigenous Peoples, this year’s EMRIP report was not of sufficient quality when it came to describing the reality that Indigenous Peoples of Russia and Ukraine face.

“The three paragraphs on Indigenous Peoples of Russia and Ukraine were very weak, furthermore, they were [compiled using] official information from Russia. For example, the information about the alternative [military] service for Indigenous Peoples of Russia. EMRIP and other UN mechanisms have to stay independent,” Tannagasheva said.

An activist from Murmansk Andrey Danilov, who took part in the session, said that “the Russian delegation is wholly made up of [representatives] of Indigenous Peoples loyal to the government”.

“Both delegates and interns of the Permanent Forum read prepared texts in an iron and emotionless voice. All of their speeches are recorded on camera by [chair of the association of Indigenous small-numbered peoples of Taymyr] Grygory Dyukarev, with the whole view of the room. So it’s not just the speech [that’s recorded] but also the reaction of the audience and who’s present. That’s unacceptable,” he wrote.

He also emphasised that the speeches of the Russian delegation boil down to praising the Russian government, without any critical remarks made.

Tannagasheva noted that the official Russian delegation uses “pet puppet aborigines” who “while receiving money from Nornickel and other large mining companies, laud Russia instead of using the opportunity provided by the UN platform to protect the rights of their people”.

The Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples session takes place 17-21 July in Geneva.

Unpacking clean energy: Human rights impacts of Chinese overseas investment in transition minerals

In the next decade, China is set to play a central role in the global transition to clean energy. This will require significant overseas investment in transition mineral mining, giving China an important responsibility to ensure the energy transition is not only fast, but also fair to workers and communities most directly impacted by Chinese overseas investments. This briefing underlines the significant improvements required in the practices and approaches of Chinese mining companies if they are to successfully contribute to the rapid, just energy transition our world needs, and to the wider social goals of the Belt and Road Initiative.

This analysis highlights the scale and scope of human rights and environmental abuses linked to Chinese companies’ operations overseas. From January 2021 to December 2022, a total of 102 allegations of abuse were recorded by the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (Resource Centre). These allegations of abuse sit alongside similar alleged abuses by North American and European companies recorded in the Resource Centre’s Transition Mineral Tracker (TMT), as well as other reports on the human rights and environmental impacts of renewable energy supply chains in the Andes, Southeast Asia, Kenya and South Africa, highlighting the risks of irresponsible business practices for vulnerable local communities, Indigenous Peoples and migrant workers around the world.

Despite important advances promoted by the Chinese Government and the mining business association (CCCMC) on overseas corporate responsibility, the overall findings of this briefing suggest human rights and environmental risks in transition mineral supply chains associated with Chinese companies, including exploration, extraction and processing, are significant.

Key findings

- Indonesia has the highest number of recorded allegations of abuse (27), followed by Peru (16), Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (12), Myanmar (11) and Zimbabwe (7).

- Over 2/3 of the allegations (69) involve human rights abuses against local communities. The most salient risks concern impacts on livelihoods, Indigenous Peoples’ rights and insufficient or lack of consultation.

- Over half (54) of the allegations involve negative environmental impacts, where water pollution, effects on wildlife and species habitat and issues with access to water access are frequently recorded.

- More than 1/3 of the allegations (35) concern workers’ rights. The majority link to health and safety risks in the workplace.

- Despite the significant number of recorded allegations, only seven of the 39 companies have published human rights policies, indicating significant room for improvement in both policies and practices.

Key recommendations: Just transition to clean energy

As these findings illustrate, further and urgent action is required to mitigate the growing risk of human rights harm related to transition mineral extraction. Lack of company action risks lost public support, conflict, suspensions, delays and rising costs – something our planet can ill-afford. A different approach, one which centres human rights and promises a swift and just transition, can be built around three, key principles:

- Shared prosperity to build public support;

- Robust human rights and environmental due diligence to mitigate social and environmental harm;

- Fair negotiations to build a stable investment environment.

As demand for transition minerals to fuel green technologies remains a global priority, the scope for human rights infringements by mining companies and their investors remains a major concern. Therefore, commitment to such principles has never been more important.

Statement on 5 July 2023

On July 5th, the Russian prosecutor general’s office declared The Altai Project an “undesirable organization”. It is the 93rd foreign organization to receive this badge of honor for meaningful and effective support of Russian civil society.

“The Russian Prosecutor’s office distorts and misrepresents legitimate community-led conservation efforts organized by local activists in Russia,” said The Altai Project director Jennifer Castner. “Their specious accusations are focused on events that occurred between 2006-2018. In making this announcement, the Russian government is only harming its own citizens – people who are working to protect their right to a clean and healthy environment.”

The Prosecutor General claims that The Altai Project has been involved in “sabotaging the construction of the Power of Siberia-2 gas pipeline, as well as propaganda work in the Russian and global community, the purpose of which is to publicly convey the need to fight for sacred places” in Altai Republic. In addition, The Altai Project opposes [mining] development … in connection with which The Altai Project causes economic damage to the Russian Federation…. While formally advocating nature conservation, it interferes in the internal affairs of the Russian Federation and may harm Russia’s economic security.”

With this announcement, the Russian authorities now categorize cooperation or interaction with The Altai Project by Russian citizens, both inside Russia and abroad, as a crime. The Russian Prosecutor General’s press release unironically states that Russian nature conservation, wildlife protection, and cultural heritage preservation are harmful to the country’s security and economic development.

Centering Russian leaders

The Altai Project has worked since its founding in 1998 to support community-led nature conservation and biodiversity protection. Until recently, rule-of-law in Russia guaranteed the rights of its citizens to live in a healthy, clean environment, balanced with the just and sustainable use of natural resources, despite increasing challenges to protecting those rights.Independent Russian citizens and Russian independent, non-governmental organizations are more than capable of identifying environmental issues in their local communities, acting to address those issues, and seeking support. Over its decades of work, The Altai Project has simply provided resources, access to expertise and collaboration, and global amplification of voices in Russian civil society.Some of their achievements include:

- Coordinating public input to decision-makers on plans for a large hydropower dam in the 2000s, resulting in its cancellation;

- Calls to re-route the Altai Gas Pipeline (renamed Power of Siberia 2) away from the ecologically-sensitive and culturally-sacred Ukok Plateau, ultimately resulting in it being rerouted to the east, away from Altai in 2016; and

- Community-led monitoring of plans to extract cobalt in key snow leopard habitat. Investors failed to close the deal and the plan evaporated in 2016;

- Restoration of the snow leopard population in Altai Republic through careful protection and study. This iconic cat has become a valuable economic driver of tourism.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and corrupt governance

When Russia launched its horrific, full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, The Altai Project spoke out publicly in solidarity with the people and nation of Ukraine, noting, “While we will pause our work in Russia, The Altai Project will continue supporting partners in conservation efforts and advocacy in other parts of Eastern Europe and Eurasia.” The Altai Project has never had any employees in Russia or maintained an office there.

“Once again, the Russian Prosecutor General has decided to stand with corrupt oligarchs instead of the Russian people,” Jennifer Castner added. “Crackdowns on international organizations (like The Altai Project) that support ordinary Russian citizen leadership to protect their natural heritage only highlight the Russian government’s weakness.”