The Ongoing Struggle for Decolonization and Recognition of the Yupik People

Luda Kinok, an Indigenous rights advocate and member of the Yupik people, reflects on the severe impact of colonization on Indigenous populations worldwide. The experiences of her community, as well as those of other Indigenous groups, are often shrouded in silence, causing immense pain and suffering that goes largely unrecognized.

In recent discussions, particularly those concerning the Indigenous peoples of Russia, the topic of decolonization has taken centre stage. This debate, fuelled by a new wave of ethnic activists who have fled Russia due to political persecution, highlights intricate historical injustices. Initial thoughts on decolonization often revolve around the decolonization movements in Africa and Asia during the latter half of the 20th century, where once-colonized nations gained their independence from European powers.

However, the situation becomes more complex concerning small nations or Indigenous groups who find themselves within newly independent states. For instance, have the Indigenous people of Greenland truly achieved decolonization, or do remnants of colonial governance still linger under Danish oversight? Despite Greenland’s extensive local governance, core matters of foreign policy, defense, and currency control remain with Denmark.

The Sami people, residing in northern Europe, provide another lens through which to examine decolonization. Though they exhibit humor about their situation—joking that they could easily form their own state but would rather engage in traditional activities like fishing and reindeer herding—the question lingers: have they reached a sufficient level of decolonization?

Sámi land, or Sápmi, faces ongoing threats from larger state interests and environmental concerns. The task ahead involves recognizing and grappling with the implications of colonialism—a conversation still deemed taboo in Russia.

During a recent session of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, a report on Indigenous self-determination prompted an official rebuke from the Russian Foreign Ministry. Sergey Chumarev’s comments displayed a defensive posture regarding Indigenous rights, especially regarding the Inuit in regions like Chukotka, where there are accusations of colonial domination.

Chumarev’s claim that the Indigenous peoples of Chukotka have achieved autonomy is met with skepticism. The underlying dissatisfaction with the representation of Chukotka as a colony reveals an unwillingness to confront the historical facts of colonialism, undermining the progress of Indigenous rights discussions.

Enter Luda Kinok, a Yupik representative who has lived through the trials of her community. Luda’s upbringing in the village of Sireniki and her journey to becoming a pastor in Chukotka highlight the deep cultural disruptions caused by colonization and Soviet policies. Her struggle serves as a personal account of the broader Indigenous experience afflicted by ideological impositions and physical displacements.

As the Yupik face the legacy of colonization, the memories of their past continue to inform their identity. Kinok poignantly notes how the Soviet narrative erased Indigenous history, relegating it to folklore and myth while asserting the supposed superiority of colonial societies.

The Soviet regime’s policies against Indigenous peoples resulted in forced relocations, undermining their social structures and traditional lifestyles. Kinok recounts the traumatic experiences of her people as they were compelled to abandon their homes and communities, leading to a generational disconnect with their cultural roots.

Today, the Yupik community experiences the consequences of historical injustices amid ongoing existential threats, most notably the war in Ukraine. Kinok’s observations on the disproportionate mobilization of Indigenous men from her community underscore the dire implications of the ongoing conflict, which eerily echoes historic patterns of oppression.

Furthermore, Kinok critiques the Russian government’s current legislation, which seems to prioritize the protection of flora and fauna while leaving Indigenous peoples marginalized and voiceless. The disparity between the attention given to plant life versus the survival of the Yupik people raises profound ethical questions about contemporary priorities in Russia.

The portrayal of the Yupik as a near-extinct population in the face of overwhelming state disregard for their identity and rights emphasizes a broader failure to protect Indigenous cultures and lifeways. As Kinok asserts, the global community needs to shift their focus from merely commemorating historical injustices to actively addressing and safeguarding Indigenous rights and cultures today.

Ultimately, Luda Kinok’s calls for recognizing the colonial past and its lasting repercussions serve as a clarion call for justice. Celebrating the resilience and wisdom of her ancestors, she urges action that not only acknowledges the reality of colonialism but also strives to rectify its continuing impact on the Yupik and other Indigenous peoples in Russia.

Indigenous Leaders to Convene at Global Summit on the Energy Transition

Summit Highlights a Rights-Based Approach and Centers Indigenous Peoples’ Priorities and Solutions

The Indigenous Peoples Global Coordinating Committee, in partnership with Securing Indigenous Peoples Rights to a Green Economy (SIRGE) Coalition, is hosting the JUST TRANSITION: Indigenous Peoples’ Perspectives, Knowledge, and Lived Experiences, an international summit taking place from October 8 to 10, 2024, in Geneva, Switzerland.

Over 100 representatives of Indigenous Peoples from the seven socio-cultural regions of the world will gather to collectively define a Just Transition and the green economy from Indigenous perspectives. The summit calls for a rights-based approach rooted in principles such as self-determination, FPIC, cultural rights, land and territorial rights, and the participation of Indigenous Peoples in decision-making processes.

Rodion Sulyandziga, Chair of the Indigenous Peoples Global Coordinating Committee, said, “For the energy transition to be truly just and effective in mitigating the climate crisis, Indigenous Peoples must be central to decision-making, leadership, and solutions. All development projects on or near Indigenous territories must receive Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) from Indigenous Peoples, as set out by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). It is important that development initiatives under the labels of green energy, green economy, climate change mitigation, and conservation do not repeat harms and rights violations of past extractive practices, particularly those against Indigenous Peoples.”

The three-day summit will feature a mix of panels and breakout sessions focusing on key issues affecting Indigenous Peoples. Topics will include transition minerals, transition agriculture, and regional case studies highlighting both negative impacts and best practices. The summit will challenge common terminology and narratives in the current energy transition and redefine the energy transition using Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge and solutions, developing shared principles and criteria for a truly Just Transition.

The first two days will be dedicated exclusively to deliberations by and among Indigenous leaders. These two days will encompass closed-door meetings to allow for in-depth discussion on critical themes and the sharing of experiences and solutions.

The morning of day three will involve the development and approval of a common position by Indigenous Peoples. The afternoon session will be dedicated to dialogue with member states, representatives of multilateral institutions, and other stakeholders. The final declaration will be approved by consensus, including agreed-upon principles, priorities, and recommendations for next steps.

The goals of the forum include:

1. To discuss and agree on criteria and principles for a rights-based Just Transition and green economy, including presenting examples and contributions based on the traditional knowledge and practices of Indigenous Peoples on the ground and in their own territories.

2. To build solidarity among impacted Indigenous Peoples of the seven socio-cultural regions.

3. To increase awareness and share information among Indigenous Peoples as well as non-Indigenous allies from the grassroots to the international levels.

4. To build opportunities for participation by impacted Indigenous Peoples in policy debates and negotiations on local, national, and international levels addressing energy transition policies and practices.

5. To amplify the voices of impacted Indigenous Peoples in decision-making at the United Nations and other international forums deliberating about the energy transition.

The Indigenous Peoples Global Coordinating Committee (IPGCC) will ensure regional and gender balance including youth engagement based on cultural understanding of each represented region. The event will center affected Indigenous communities. The working language of the Summit will be English with interpretation services provided in Spanish, Russian, Portuguese, and French.

To learn more about the upcoming summit, visit: IndigenousSummit.org.

For media folks interested in attending the summit, please send an email to noreen@sirgecoalition.org.

About

The Indigenous Peoples Global Coordinating Committee (IPGCC) consists of Indigenous leaders and organizations from all seven socio-cultural regions that are coordinating and hosting the first Indigenous Peoples’ summit on a Just Transition to develop the common position and the Indigenous Peoples Declaration based on their values, principles, and vision.

The Securing Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in the Green Economy (SIRGE) Coalition implements transformative solutions to secure the rights of Indigenous Peoples in the global transition to a green economy. The SIRGE Coalition emphasizes the urgent need to operationalize Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) and ensure Indigenous Peoples’ right to self-determination in the transition mineral supply chain, as enumerated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Coalition is comprised of First Peoples Worldwide, Cultural Survival, Earthworks, Batani Foundation, and Society for Threatened Peoples, with new affiliate member International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA).

Media Contact: noreen@sirgecoalition.org

To Prevent Harm and Uphold Rights, ICMM Must Address the “Critically Weak” Indigenous Peoples’ Policy

Statement from the Securing Indigenous Peoples Rights in the Green Economy (SIRGE) Coalition about the International Council on Mining and Metals’ (ICMM) Position Statement on Indigenous Peoples

On August 8, the International Council on Mining and Metals, a mining industry trade association representing one third of the global mining industry, released a new position statement on Indigenous Peoples. The Securing Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in the Green Economy, or SIRGE Coalition urges ICMM to revise, correct and strengthen this statement to address critical gaps and shortcomings that threaten perpetuating the mining industry’s historical harms to Indigenous Peoples. Given that over half of all mining for energy transition minerals globally are on or near the territories of Indigenous Peoples, ICMM must ensure its members operate in a manner that fully respects and upholds the rights of Indigenous Peoples.

While the updated ICMM position statement acknowledges Indigenous Peoples’ rights, SIRGE notes that it allows for a wide degree of flexibility and interpretation potentially putting Indigenous Peoples and their rights at serious risk. The SIRGE Coalition urges ICMM to require that its mining company members to fully commit to obtaining Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) as enumerated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

ICMM must clearly state that no project can proceed without the explicit Free, Prior and Informed Consent of affected Indigenous Peoples. This requirement must be absolute—if consent is withheld, the project must not move forward.

ICMM’s reliance on States to fulfill Free, Prior and Informed Consent obligations is a critical flaw. As a standard bearer for industry, ICMM policy should recognize that State standards may be inadequate, insufficient or non-existent compared to accepted international standards. ICMM members are among the world’s largest and wealthiest mining companies in the world, and must take direct responsibility for ensuring their operations fully respect Free, Prior and Informed Consent as outlined by UNDRIP. ICMM members must implement and operationalize these policies with full participation of impacted Indigenous Peoples, especially in contexts where States fail to uphold Indigenous Peoples’ rights.

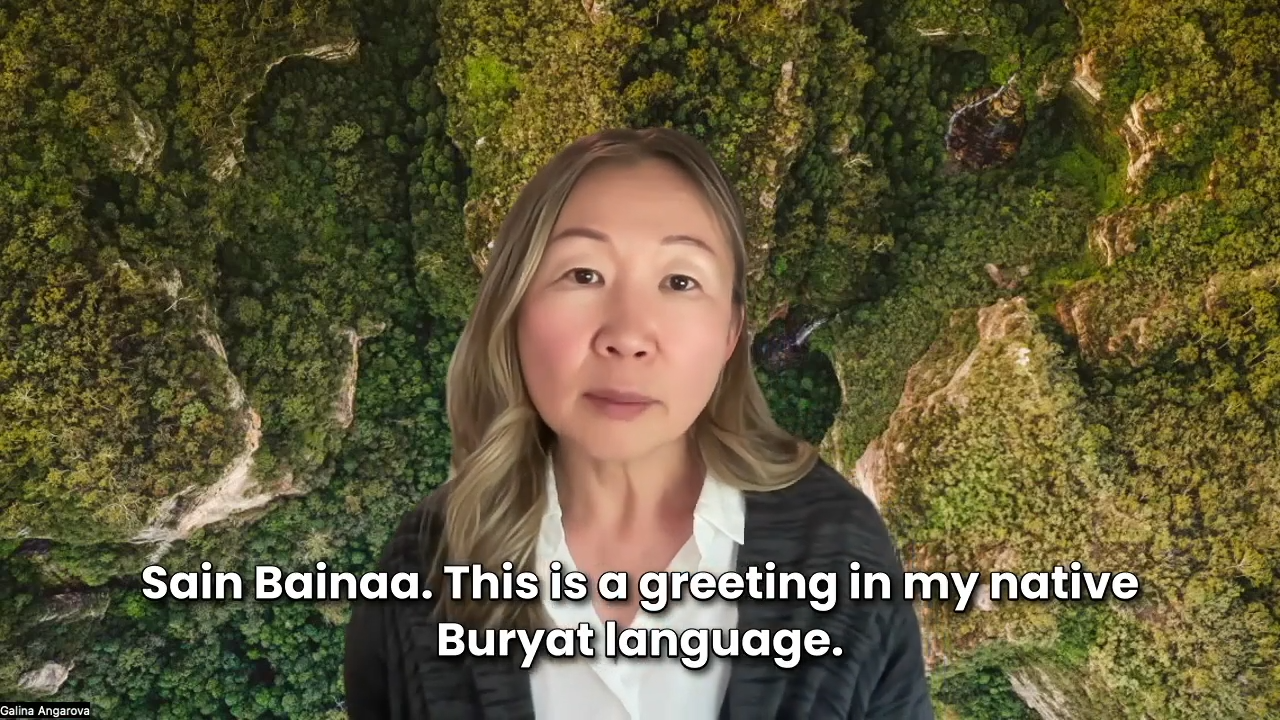

“We recognize that ICMM has made efforts to improve its Indigenous Peoples’ Position Statement but it falls short and places Indigenous communities at continued risk from mining activities. If mining companies want to comply with international standards for Indigenous Peoples’ rights and ensure their Social License to Operate when they operate on the traditional lands and territories of Indigenous Peoples, ICMM must include stronger commitments,” said Galina Angarova, Executive Director of the SIRGE Coalition. “Many Indigenous Peoples’ communities distrust the mining industry due to the historic legacy of harm that mining companies have left behind on Indigenous lands and territories. Mining companies must always respect Indigenous Peoples’ rights to self-determination and to offer or withhold their Free, Prior, and Informed Consent.”

Furthermore, the policy’s inconsistent use of terminology – interchanging the terms “agreement” and “consent” – not only creates confusion but allows for misinterpretation of legally defined terminology. Free, Prior and Informed Consent is Indigenous Peoples’ right to say “yes,” “no,” or “yes” with qualifications. While agreements can be expressions of consent and self-determination, they can only be achieved when Indigenous-defined Free, Prior and Informed Consent priorities, processes, and protocols are fully integrated and operationalized. ICMM and its members must consistently use the term “consent” or “Free, Prior and Informed Consent” avoiding the substitution of these terms with “agreements” or “consultation.”

ICMM’s position also fails to address the ongoing harms from past projects, leaving unresolved impacts on the rights and well-being of Indigenous Peoples. Free, Prior and Informed Consent commitments must be applied in a manner that addresses past harms and continued impacts from existing mining activities.

The SIRGE coalition notes additional concerns with the ICMM position statement, including the lack of clear guidelines for enforcing Free, Prior and Informed Consent, insufficient due diligence requirements, inadequate protections for Indigenous Peoples in Voluntary Isolation and Initial Contact, and the lack of directives for engaging vulnerable populations, particularly Indigenous women and elders.

The SIRGE Coalition supports the recommendations outlined in critical analysis, which concludes:

“The ICMM’s Position Statement shows a minimal effort to align with the principles of UNDRIP, ILO 169, IFC PS7, and the UNGPs; significant improvements are necessary to truly uphold these international standards. The ICMM must eliminate ambiguity in the application of FPIC, apply these updated commitments retrospectively, address potential conflicts between State and corporate responsibilities, ensure the participation of vulnerable Indigenous Peoples, make no contact with Indigenous Peoples in Voluntary Isolation and Initial Contact, establish robust monitoring mechanisms, implement clear redress and remediation processes, and enhance the protection of Indigenous cultural heritage. Only by addressing these critical areas can the ICMM ensure that its practices genuinely respect and uphold the rights of Indigenous Peoples, fostering sustainable and equitable development.”

As published, ICMM’s deeply flawed position allows the continuation of harm to Indigenous Peoples by mining operations and calls into question ICMM’s stated commitment to respecting Indigenous Peoples’ rights. Mentioning international frameworks without robust accountability mechanisms undermines the instruments to uphold Indigenous Peoples’ rights.

The SIRGE Coalition calls on the ICMM and other standard setting bodies working towards a consolidated mining industry standard, to correct, strengthen and provide more clarity in their Indigenous Peoples policies, or run the risk of perpetuating harms and rights abuses.

Galina Angarova’s Address on International Indigenous Day: A Call for Unity and Action

In this message from Galina Angarova, the Executive Director of the SIRGE Coalition discusses the importance of safeguarding Indigenous rights and lands in the context of global climate solutions. Galina emphasizes the need for meaningful inclusion of Indigenous voices in decision-making processes and highlights the role that Indigenous peoples play in protecting biodiversity and combating climate change.

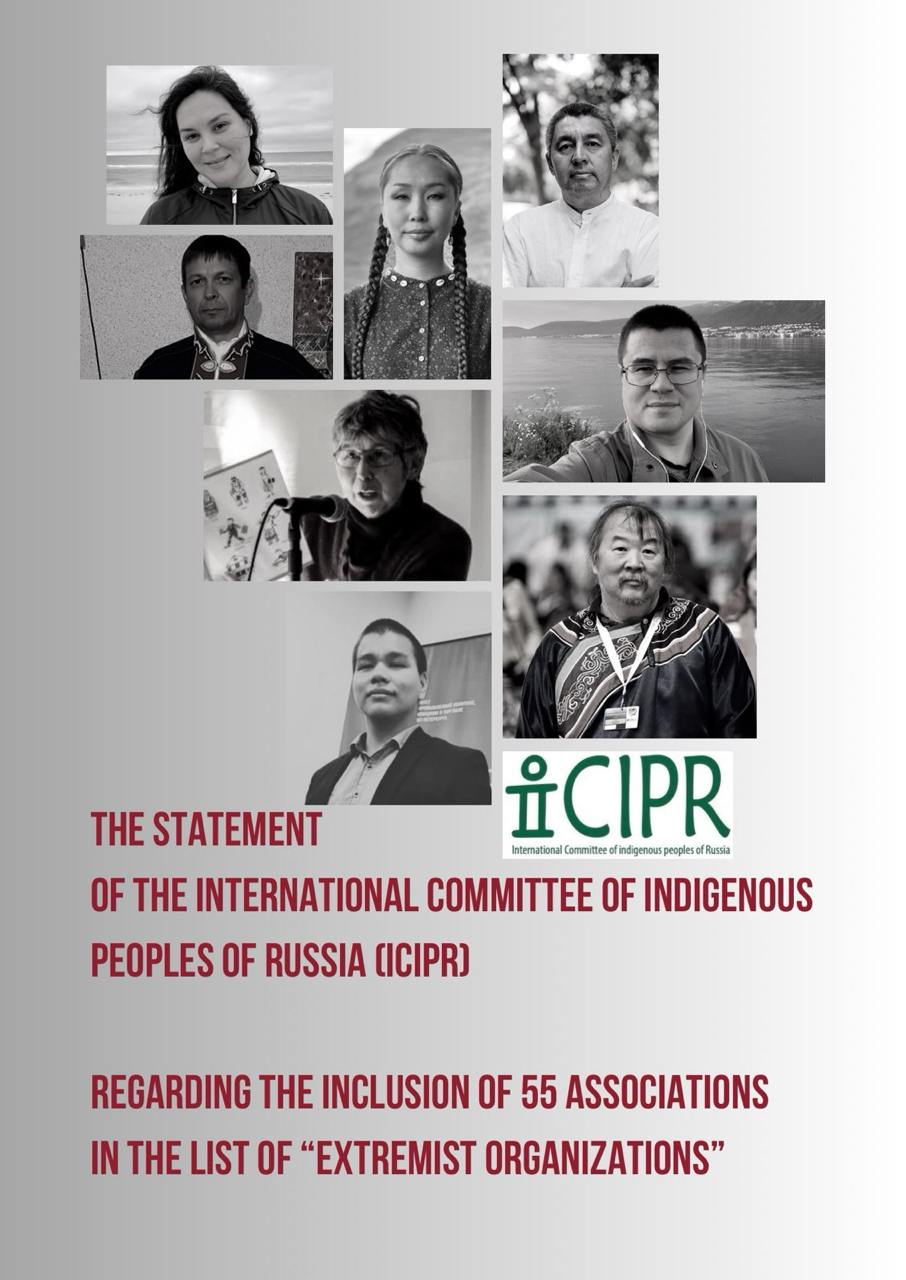

THE STATEMENT OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES OF RUSSIA (ICIPR) REGARDING THE INCLUSION OF 55 ASSOCIATIONS IN THE LIST OF “EXTREMIST ORGANIZATIONS”

The International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (ICIPR) expresses extreme concern and indignation over the inclusion of 55 indigenous peoples’ organizations, national minorities, decolonial, and other associations in the list of “extremists” by the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation.

Aborigen-Forum, an informal association of independent experts, activists, leaders, and public organizations of the indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East, also appeared in the list.

The list also includes the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (ICIPR), according to the publication on the website of the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation.

Earlier, we expressed concern when, on June 7, the Supreme Court of Russia, at the request of the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation, recognized the so-called “Anti-Russian Separatist Movement” as an extremist organization. We feared that, since such an organization does notify exist and the wording is very broad, any organization criticizing the Russian authorities could be included under this decision.

Now it is evident how this decision is being implemented. The organizations defending the rights of indigenous peoples are being included into the list of the “extremist” organizations.

Andrey Fedorkov, the lawyer who collaborates with the human rights project Support for Political Prisoners. Memorial, comments for Idel.Realii:

Currently, anyone who displays any symbols of their region, used by any organization advocating for the freedom and independence of their region, is at risk. This includes anyone who distributes relevant materials or provides links related to this topic.

We can see how absurd the application of the law is. My prediction is that a significant number of criminal cases will follow based on these articles.

Our committee also sees this as a reaction from the Russian government to the participation of indigenous movements in international platforms, such as the UN.

Just two weeks ago (July 8-12, 2024), a session of the UN Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP) concluded in Geneva, where members of our organization raised issues of human rights violations against indigenous peoples in Russia, as well as Russia’s influence on UN bodies.

Additionally, shortly before the UN session, ICIPR published a report on the Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East of the Russian Federation (RAIPON), which is controlled by the Russian government.

• It is important to note that immediately after the EMRIP session in 2022, Russia blocked our website iRussia.

• In 2023, after the EMRIP session, ICIPR member and indigenous human rights defender Pavel Sulyandziga was added to the list of foreign agents.

• And now, in 2024, after the EMRIP session, we have been included in the “extremist” list.

WE SEE THAT THE REPRESSIVE MACHINE IS GATHERING MOMENTUM.

THE METHODS OF PERSECUTION AGAINST INDIGENOUS RIGHTS ACTIVISTS ARE INTENSIFYING.

The International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (ICIPR) is an international organization of indigenous peoples, established in March 2022 as a response by several leaders and activists of indigenous peoples of Russia to the onset of the war in Ukraine.

All founding members of ICIPR were previously activists or community leaders of indigenous peoples in Russia and were forced to leave the country for various political reasons.

The aim of ICIPR is to promote the rights of indigenous peoples of the Russian Arctic, Siberia, and the Far East to their traditional lands, resources, and self-determination at national and global levels during wartime and amidst political repression in Russia.

WE, representatives of the indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East, are deeply alarmed by our inclusion in the “extremist list.” We express our extreme concern regarding the protection of indigenous peoples’ rights in this situation.

WE, as representatives of the indigenous peoples of Russia, stand in solidarity with other associations that have also been included in this list.

WE call upon all international organizations, NGOs, as well as intergovernmental, scientific, and human rights bodies, including the UN, the Council of Europe, and the Arctic Council, to CONDEMN the decision of the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation to include 55 organizations in the “extremist” list.

WE ASK FOR SUPPORT IN THE STRUGGLE OF THE INDIGENOUS PEOPLES OF RUSSIA FOR THEIR RIGHTS.

Translated from

Yana Tannagasheva’s Address at the 17th Session of UN EMRIP: A Voice for Indigenous Rights in Russia

Thank you, Mr./Madam Chair, for the floor.

The Russian government talks all the time about the colonialism of IP in other countries but has never said that the IP of the North, Siberia and the Far East were also colonized and continue to suffer. The everyday reality of the Indigenous Peoples of Russia is profoundly different from the rights described by Russian government and some of non-independent Indigenous representatives from Russia.

At this time, I am going to speak on behalf of three Indigenous women (Buryat and Sakha Indigenous Peoples of Russia) who applied to attend this session, but for unknown reasons, unfortunately, were denied at the same time and were unable to travel to Geneva, although their tickets had already been purchased. These three strong activists represent anti-war organizations working on decolonial issues and drawing attention to violations of Indigenous rights in Russia and the impact of the war in Ukraine on their communities.

I will read their message.

We, the undersigned Indigenous activists of Russia, are deeply concerned about the current tendency at the UN of Russia’s introducing its representatives into international human rights and Indigenous Rights mechanisms, and we are also very concerned about the exclusion of independent Indigenous voices from Russia from mechanisms such as the UN EMRIP and the PFII.

We were not allowed to attend the 17th session of the EMRIP, but we hope that our voices will still be heard loudly. We believe that preventing independent representatives of Indigenous Peoples of Russia from attending UN sessions is a strong influence of the Russian Federation. Russia is trying to spread its propaganda in every possible way. Those who manage to participate in UN sessions are being pressurized by the Russian authorities in every possible way.

Russia needs the natural resources of Indigenous Peoples. By selling it, the country earns billions of dollars to wage wars, to maintain a high level in the capital, to generously feed the power structures and keep the oligarch class and the elite loyal. Unfortunately, some Indigenous People’ representatives fall under such influence. Such Indigenous representatives become a tool of Russia’s propaganda.

We call on the EMRIP, the PFII, the VF, UN treaty bodies, and the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to pay special attention to the representation of Indigenous Peoples of Russia, and we ask for ensuring the full and unhindered participation of independent Indigenous representatives in all future processes. It is very strange that the Association of the IP of Yamal made the same statement twice today. But nobody from independent indigenous from Russia.

We believe in the independence and commitment of UN mechanisms to freedom, inclusiveness, universality in the protection of Human Rights and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Thank you!

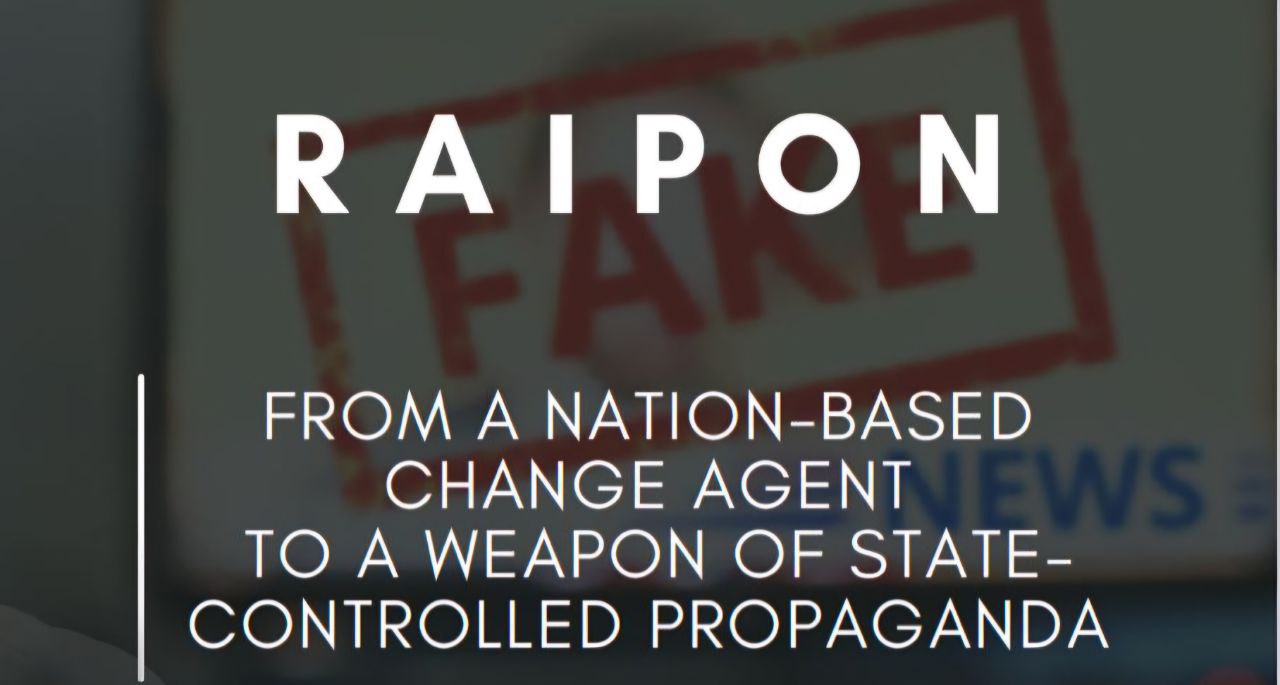

Report on RAIPON (Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North)

The International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia announced the release of a detailed report. The report is on the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON). This in-depth analysis raises serious concerns about RAIPON’s recent transformation and evolving role as an instrument of state propaganda.

Key insights from the report include:

- A timeline of RAIPON’s increasing alignment with state interests, often at the cost of genuine indigenous advocacy.

- Actions that undermine the true representation of indigenous communities.

- The potential consequences for the future of indigenous rights and representation in Russia.

We acknowledge the significant impact these developments have on the global community. We emphasize the need for open and transparent discussions. This report marks a vital step toward restoring the integrity and mission of indigenous advocacy in Russia.

COP28 Organization Sign-On Letter: Ensure Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Are Secured in the “Green” Transition

Dear COP28 Delegates,

We, Indigenous leaders and allies from diverse cultures, traditions, and regions across the globe, are united in calling for COP28 to be a platform to discuss Indigenous Peoples’ rights in the context of the increasing demand for minerals mined for energy storage, electrified transportation batteries, and other green energy technologies. In our call, we urge for governments and corporations to respect, protect, and fulfill Indigenous Peoples’ rights, specifically the right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), as the minimum standards enumerated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the ILO Convention 169, to ensure equitable and responsible environmental and social practices on our lands.

We acknowledge and emphasize that it is more important than ever to transition to clean energy and clean transportation solutions, and away from fossil fuels such as oil, coal, and gas. Indigenous leaders have been calling for climate action around the world for decades. We have ancestral, cultural, and spiritual ties to our lands that not only require our participation in climate advocacy but also call us to commit to the proper stewardship practices of nature that are deeply rooted in our ways of life. Many Indigenous leaders are pursuing and championing clean energy and transportation solutions on their territories that align with their self-determined needs and goals. These Indigenous-led solutions need to be acknowledged, recognised, promoted, and funded by States and private entities.

While we are at the forefront of the fight for climate action and clean energy, our profound connection to our ancestral lands also puts us on the frontlines to ensure that these lands will not be sacrifice zones for those companies and politicians who seek a quick fix in the name of climate solutions. Our commitment to a just transition doesn’t overshadow our firm stance against mining practices that occur without obtaining FPIC of Indigenous Peoples and can lead to displacement; migration; and livelihood, cultural, and language loss. We firmly assert that mining operations must adhere to responsible practices guided by the FPIC framework, which upholds the right to self-determination of Indigenous Peoples. We, Indigenous Peoples, hold an inherent and inalienable right to make decisions about the future of our lands, territories, and resources.

The historic exploitation of our people and lands by oil, gas, and mining companies showcases a legacy of putting profits over our well-being, health, safety, cultures, traditions, and our sacred lands, waters, and air. With 54% of energy transition minerals globally located on or near our Indigenous Peoples’ lands, it is imperative that our communities participate meaningfully in decision-making and are able to exercise our right to give or withhold consent to these projects that will impact our lives, livelihoods, and cultures.

Ignoring our voices will only perpetuate the fossil fuel and mining industry’s status quo. Instead, if and when new mines are proposed on our ancestral lands, Indigenous Peoples must be involved from the start. Our subsistence, cultural practices, and priorities must be at the center of negotiations for proposed mines on our lands. We need to be involved in policies and enhanced levels of engagement and transparency at every step of the process. These must be co-developed with our participation and according to our leadership and governance structures.

The most protective way to achieve this is for governments and businesses around the world to ensure the highest standards of FPIC occur for every proposed minerals mining project that impacts Indigenous Peoples. As articulated in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which was adopted by the United Nations in 2007 and endorsed by many countries throughout the world, FPIC expresses consent-based protocols defined by Indigenous leaders, secures decision-making authority and participatory rights in all decisions that affect Indigenous communities and territories, and helps understand the full impacts of projects affecting Indigenous Peoples lands, subsistence, and cultural practices, and ways of life.

FPIC encompasses Indigenous Peoples’ right to:

- Enter into conversations and negotiations without coercion or manipulation.

- Engage in consultations and decision-making processes long before decisions are made concerning their land, resources, individuals, and communities.

- Utilize their own traditional decision-making structures/governance, ensuring that these structures are respected and integrated into the process.

- Have full information that is easily accessible and readily available in a language they understand.

- Say “yes” or “no” to a project.

- To be involved and heard throughout a project’s life cycle wherever it impacts people and resources.

- Retain the ability to withdraw consent at any stage of the project or activity if circumstances change or new information arises that affects their consent.

- Receive support and resources necessary for effective and meaningful participation in discussions and decision-making processes.

We will not back down from our role as leaders in the fight for climate action and clean energy. COP28 must be the foundation for governments around the world to build on this momentum and take the urgent steps needed to secure Indigenous Peoples’ self-determination as reflected in UNDRIP and as defined by impacted Indigenous Peoples so that the world can get this transition right, take the required climate action, and avoid making the mistakes of the past that have put our people and ways of life at risk, and have pushed planetary boundaries to dangerous limits. In the spirit of this effort, we believe it is an opportunity to define a better and more inclusive world that serves all communities and all peoples – transcending the boundaries of concentrated political and economic power. In this collective vision, we are committed to protecting our shared cultural heritage and practices that bind us together and to continue being responsible stewards of the planet.

Thank you for your time and consideration.

Signed,

1. Securing Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in the Green Economy (SIRGE) Coalition

2. Cultural Survival

3. First Peoples Worldwide

4. Batani Foundation

5. Earthworks 6. Society for Threatened Peoples