We can’t mine our way out of the climate crisis

Global upswell of civil society organisations, communities and academics tells EC to align raw materials sourcing plans with the interests of people and planet.

Over 230 civil society organisations, community platforms and academics are urging the European Commission to reassess its plans for sourcing the raw materials it claims Europe will need to realise energy, industrial and military transitions.

The Commission’s plans risk destroying climate-critical ecosystems and sowing social conflict in Europe and in the Global South, authors of a collective letter that has received global support have warned.

The letter comes in response to the Commission’s forth September announcement of a new Raw Materials Action plan, which sets out how to meet Europe’s growing demand for ‘critical’ raw materials, such as lithium and cobalt, used in renewables and other strategic industries.

Extraction

While the Commission speaks of its plans in terms of sustainability and a green recovery, the letter raises serious concerns that Europe’s current plans for sourcing critical minerals and metals will be far from sustainable.

Instead, the authors argue, plans to intensify resource extraction to meet growing demand, if realised, will place communities, biodiversity and even climate action at risk.

Guadalupe Rodriguez, who works on forest and extractive issues for Spanish NGO Salva La Selva, said: “The European Commission’s plans are encouraging mining projects in both the Global South and in European countries like Portugal and Spain, which we could call the ‘South of the North’.”

“In these places mining is causing ecological devastation, while new mining proposals are full of irregularities, lack transparency and are faced with growing resistance from local citizens, which is being ignored.

“Far from achieving a ‘green transition’, the Commission’s current plans effectively push for business as usual in line with European interests, at the cost of communities and the Earth.”

Own-goal

Plans to expand mining globally to meet the massive projected growth in mineral and metal demand, partly driven by transitions to renewable energy, could undermine climate change mitigation efforts by destroying biodiverse ecosystems essential to the functioning of the global climate system, the latest scientific studies show.

A new paper published in the prestigious Nature Communications Journal this month found that: “Mining potentially influences 50 million km2 of Earth’s land surface, with 8 percent coinciding with Protected Areas, 7 percent with Key Biodiversity Areas, and 16 percent with Remaining Wilderness … Most mining areas (82 percent) target materials needed for renewable energy production”.

These numbers are set to increase in a global, market-led rush for so-called critical minerals and metals. The authors of the study conclude that, if this boom goes unchecked, “new threats to biodiversity (from mining) may surpass those averted by climate change mitigation.”

Hal Rhoades, northern European coordinator of the Yes to Life, No to Mining Network, said: “We cannot mine our way out of the climate crisis.”

“To display true climate leadership, the EC needs to establish and put in place policies for a low-energy, low-material transition in Europe, with a far greater focus on demand reduction and recycling. It also needs to contribute a fair share of support to Global South nations to redress the relentless, centuries-long extraction of wealth from the South to Europe.”

Demands

By refusing to consider options for de-growing Europe’s material consumption and alternative means of measuring wellbeing and progress other than GDP, the authors argue that the European Commission’s latest action plan represents business as usual and a threat to ambitious climate action.

While the European Commission’s new Action Plan does mention the importance of recycling and a circular economy, the authors of the open letter challenge the fundamental logic of economic growth that underlies the plans and policies.

They lay out a series of alternative recommendations to the Commission which could help put Europe on course for a truly just, green and sustainable future, including:

- An absolute reduction of resource use and demand in Europe

- Recognition and respect for communities’ Right to Say No to mining

- Enforcement of existing EU environmental law and respect for conservation areas

- An end to exploitation of Global South nations, and respect for human rights

- Protection of ‘ new frontiers’ – like the deep sea- from mining.

Speaking to these recommendations, Meadhbh Bolger, resource justice and new economies campaigner for Friends of the Earth Europe, said: “Europe’s desperate plunder for more raw materials must stop. We need a truly just and equitable transformation to a 100 percent renewable energy future and an economy within environmental limits. This means rich countries must reduce our consumption of resources, respect communities’ right to say no to mining, and end exploitation.”

This Author

Marianne Brooker is The Ecologist’s content editor. This article is based on a press release from Yes to Life, No to Mining.

Human rights defenders who engage with UN continue to be threatened and attacked

The UN Secretary-General released his annual report today on reprisals and intimidation against individuals and groups seeking to cooperate with the UN on human rights. Once again, the report identifies a very concerning number of threats and attacks aimed at silencing human rights defenders in retaliation for engaging with the UN, with evidence that a number of States have a strategy or systematic approach to obstructing and punishing those who give information, evidence or testimony in relation to human rights.

‘The Secretary-General’s report is appalling. Human rights defenders are integral to the international human rights system. If they are not able to safely share information about violations and abuses taking place in their countries, the entire system is undermined,’ said Madeleine Sinclair, New York Office Co-Director and Legal Counsel at ISHR.

ISHR contributed to the report through a submission documenting a number of cases. These demonstrate a disturbing pattern. Cases of reprisals featured in the submission range from States dangerously maligning defenders to killing them. In Venezuela, increased monitoring of the situation by the UN has been met with increased risk, stigmatisation and harassment of defenders working with the human rights mechanisms. In the Philippines, human rights defenders continue to be vilified by the government and accused of being terrorists. Defenders in Honduras, India, Thailand, Cuba and Yemen continue to be threatened and harassed. In Russia and Cameroon, defenders who engaged with the UN have been refused entry to the country. Defenders working on China continue to be smeared and discredited and there continues to be no investigation into the death of Cao Shunli, who was jailed and died in custody for trying to provide information to the UN. Defenders in Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia remain in jail because they dared to engage in international advocacy. Other countries cited in ISHR’s submission include The Bahamas, Brazil, Burundi, Mexico, Morocco, and the United States.

‘Around the world, human rights defenders continue to work tirelessly for a society that is more free, equal, just and sustainable. Because of their work, defenders continue to face unacceptable risks. They are threatened, harassed, stigmatised, attacked, jailed, even killed— there is much work to be done to ensure defenders can safely engage with the UN,’ added Sinclair.

The SG’s report documents cases from 45 countries. The vast majority are countries that have been cited in the report before. New countries cited this year include Andorra, Cambodia, Comoros, Equatorial Guinea, Laos and Libya. The report also documents a much larger number of countries where a pattern of intimidation and reprisals is occurring (11 this year, compared to three last year). These include Bahrain, Burundi, China, Cuba, Egypt, India, Israel, Myanmar, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka and Venezuela. Nearly all cases addressed in previous Secretary-General reports have not been adequately resolved.

‘Is this report working as a means of addressing the problem if the cases and number of perpetrating States remains so high, and there is little to no satisfactory resolution of cases once they’ve been documented? What does seem to ‘work’ is reprisals – they dissuade engagement, and perpetrators are emboldened when nothing is actually done about these attacks’, said Sinclair.

‘Documenting reprisals in a report is important but it’s only the first step. The UN and Member States must do more! We need consistent and meaningful follow up and we need more States speaking out loudly and often about these shocking cases. The report is presented every year to States: States should use that opportunity to hold their peers accountable, speak out about specific cases, push for accountability, an end to impunity, and reparations for victims,’ Sinclair concluded.

Once-in-a-lifetime opportunity

The International Energy Agency (IEA), together with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), proposed a sustainable recovery plan to world governments. There will be no better time to move the economy into a green direction, experts say. Representatives of the Russian Socio-Ecological Union, who’ve launched an initiative to collect proposals for a green recovery from the crisis, agree with them.

Since the signs of the economic crisis began to manifest, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has repeatedly called on governments to make the recovery as sustainable and green as possible. That is, to emerge from the global recession through cleaner and safer energy systems. In recent months, energy economists have also joined in searching a way to recover from the pandemic.

A remarkable tandem, the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have released the Sustainable Recovery Plan. As the developers of the document say, they are driven by the “sense of urgency of the moment”. “Governments have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to reboot their economies: they can turn 2020 into a year, when the world starts to win both climate change and coronavirus,” says Fatih Birol, head of the International Energy Agency.

The Sustainable Recovery Plan offers governments a three-year roadmap in the energy sector to stimulate economic growth, create millions of jobs and reduce global emissions. The energy policy transformation in response to the economic shock caused by the Covid-19 crisis should accelerate the introduction of modern, reliable and clean energy technologies and infrastructure changes, the plan says.

“Together with the IMF, we have reviewed all possible energy strategies and focus on those that will meet three objectives: stimulate economic growth, create jobs and avoid a recovery in greenhouse gas emissions. And we put forward three proposals: first, to improve energy efficiency, especially in the construction sector; second, to promote the use of renewable energy sources; and third, to modernise and digitize electricity networks,” explains Fatih Birol.

The Sustainable Recovery Plan is based on detailed assessments of more than 30 specific energy policy measures in three categories: electricity (including renewable energy), expansion and strengthening of electricity networks, development of electric vehicles and charging infrastructure, energy efficiency measures in buildings, industry and transport, and a separate category for “new technologies,” such as energy storage systems and hydrogen. The measures in the plan will require a global investment of $1 trillion. One third of the funding is expected to come from governments and the rest from private sources.

According to the IEA and IMF Plan, global economic growth would be, on average, 1.1 per cent per year higher than without green recovery measures. At the same time, about 9 million jobs will be created and retained annually, and by the end of 2023, emissions will be 4.5 Gt lower than at present. Implementation of the plan will also contribute to achieving the UN’s sustainable development goals: improving air quality by 5%; providing access to clean energy for 420 million people and electricity for 270 million.

The global energy sector will also become more resilient, which will make countries more prepared for future crises. If the Plan is implemented, 2019 will be the last peak in global emissions, enabling the global community to meet long-term climate targets and the Paris Agreement.

In their document, the IEA and IMF highlight key aspects of the current situation that make it unique: “Compared to 2009, we have at least three main advantages. First, the cost of clean energy technology is now much lower. Secondly, this year’s emission reduction is very steep. And thirdly, many governments around the world are taking environmental climate issues much more seriously today than they were a decade ago. So we hope that governments will pass the test this time,” says Fatih Birol.

“Even if we forget about the climate and environment, the implementation of the strategy presented by the IEA and IMF creates jobs and helps to lift the economy,” write the developers of Sustainable Recover.

During the IEA Ministerial Summit in early July, leaders from four-fifths of the world’s energy consumption were invited to discuss ways to accelerate the clean energy transition and a recovery plan. According to experts, Europe has already developed a very strong incentive package for renewable energy. Canada and Japan have also taken steps in this direction.

Civil society representatives have also stressed the need for green recovery strategies. The Russian Social and Ecological Union (RSEU) together with non-governmental organizations of the world within the framework of the Just Recovery initiative addressed politicians, economists, governments and banks demanding that they use only environmentally friendly and socially responsible ways out of the crisis. Recently, Greenpeace Russia and the RSoEU have jointly launched a platform to put together proposals for a green recovery.

THE WORLD NEEDS SOLIDARITY. YOUR CONTRIBUTION COUNTS.

The United Nations is marking its 75th anniversary at a time of great challenge, including the worst global health crisis in its history. Will it bring the world closer together? Or will it lead to greater divides and mistrust? Your views can make a difference.

Covid-19 is a stark reminder of the need for cooperation across borders, sectors and generations. The UN Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres, has said:“Everything we do during and after this crisis must be with a strong focus on building more equal, inclusive and sustainable economies and societies that are more resilient in the face of pandemics, climate change and the many other global challenges we face.”

Your responses to this survey will inform global priorities now and going forward.

Ceremonies for Sk’alich’elh-tenaut

The Lhaqtemish people of Lummi Nation have lived in a reciprocal relationship with Xw’ullemy (the Salish Sea bioregion) since time immemorial. They are people of the sea whose culture, sacred sites, and life ways are tied to their territorial waters, and to the orca whales and salmon who share those waters.

The Lummi term for “orca” is “qwe’lhol’mechen,” which loosely translates into “our relations under the waves.” Lummi teachings hold orca whales are simply people in whale regalia, and that Lummi people and the resident orcas are bound by ties of intermarriage, society, and spirit. Lummi and qwe’lhol’mechen cultures mirror each other in many ways: we both rely on Chinook salmon; our teachings and rituals are passed down through the generations; and our families are tight.

Another way in which Lummi and qwe’lhol’mechen experiences are similar is the trauma of colonization and child abduction. Many Lummi children were stolen from their families and placed into boarding schools where they were forced to hide their language, culture, and spirituality. Our qwe’lhol’mechen also went through a time when their children were stolen.

50 years ago, a young qwe’lhol’mechen was violently taken from her family in the Salish Sea. She was stolen from her mother, from her resident orca relations, and from her Lummi relations. She was captured by men and sold to the Miami Seaquarium. Her captors called her “Tokitae;” the Miami Seaquarium gave her the stage name “Lolita.” Her Lummi name is Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut.

She has been held in a tiny concrete tank for 50 years and made to perform daily for her food. For decades, many people and organizations have fought to free her, but have been unsuccessful in their attempts. Now, however, two Lummi women are invoking their unique legal rights as Indigenous people, as well as their cultural, spiritual, and kinship rights, to bring Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut home to her Salish Sea family. Squil-le-he-le (Raynell Morris) and Tah-Mahs (Ellie Kinley) are backed by the expertise of the Earth Law Center and the Whale Sanctuary Project.

Bringing Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut home will help heal her, her family, the Lummi people, and the Salish Sea. This act of healing will resonate with other acts of healing throughout the world, wherever Indigenous people are working to save the lands and waters they call home. This is not simply practical or legal work, it is spiritual work. For this reason, we are holding an international, collective ceremony for Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut.

We are respectfully asking if you might hold ceremony, in your own cultural way, for Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut. For Tah-Mahs and Squil-le-he-le, holding ceremony for Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut means placing cedar boughs on the sea waves and saying a prayer for Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut, but we honor whatever way you hold ceremony, and are grateful for your spiritual and cultural support. We would be further honored if you might video your ceremony and allow us to share a clip during our virtual event on September 24th, as well as post it on our Ceremonies for Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut Facebook page.This way, people around the world can witness one another’s ceremonies, and we can send a collective prayer to her.

Hy’shqe! (Thank you).

Facebook page “Ceremonies for Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut”: https://www.facebook.com/Ceremonies-for-Skalichelh-tenaut-111624844000057

The Federal Security Service (FSB) took control over the creation of the new registry of indigenous peoples of the Russian Arctic, Siberia and the Far East

Compilation and maintenance of the list of small-numbered indigenous peoples of the Russian Federation became another function of the governmental system of monitoring in the sphere of interethnic and interreligious relations and early conflict prevention to be operated by FADN (Federal Agency of Ethnic Affairs). An appropriate ruling was signed by the Russian Prime Minister, Mikhail Mishustin.

The system of monitoring of the interethnic sphere was launched at the end of 2016. By the end of 2017, it was implemented in all regions of the Russian Federation. At the same time, the Government approved the goals and objectives of the monitoring system in the sphere of interethnic relations.

According to the new amendments, “one more function of the monitoring system, besides the identification of and response to the conflict situations, will be “registration of persons belonging to the small-numbered indigenous peoples of the Russian Federation” and “compilation of the list of persons belonging to them.”

These amendments concluded the many years of work aimed at creating united registry of the small-numbered indigenous peoples of Russia, which was handed over to the Federal Agency of Ethnic Affairs last June.

The authors of this governmental ruling assume that the registry will resolve one of the main problems of indigenous peoples by simplifying their access to the natural resources they traditionally use. They would also not have to collect and submit documents every year because the list will contain all relevant information.

This will be the first example of compilation and maintenance of a nationwide list of the small-numbered indigenous peoples in Russian history. Historically such registers existed locally in some regions only.

Compilation of the indigenous peoples’ registry was actively supported by the Russian Association of indigenous peoples of the North (RAIPON) and its president and deputy of the RF State Duma Grigory Ledkov. In one of the interviews, he said that “this federal law will let the Association pursue systemic activities to improve the lives of indigenous peoples.”

It should be noted that the development of monitoring the sphere of interethnic and interreligious relations was started in 2015. In February 2016, the President of Russia instructed the FSB (Federal Security Service), General Prosecutor’s Office, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Telecom and Mass Communications, Roskomnadzor, and FADN (Federal Agency of Ethnic Affairs), with other Federal Government stakeholders, to submit their proposals on the organization of information threats’ monitoring on the Internet.

This instruction was given to Alexander Bortnikov, FSB Director, Yuri Chayka, RF General Prosecutor, Alexander Konovalov, Minister of Justice, Nikolai Nikiforov, Minister of Telecom and Mass Communications, Alexander Zharov, Roskomnadzor Director, Igor Barinov, Director of the Federal Agency of Ethnic Affairs. However, Alexander Bortnikov, FSB Director, was appointed an official in charge.

According to the Federal Agency of Ethnic Affairs, the national system of monitoring the inter-ethnic and inter-religious relations and early prevention of the conflict situations created by FADN is designed primarily to identify illegal online activities. All regions of the Russian Federation are connected to the system; 48 of them had their municipal units connected to it, which, according to FADN, enables the maximum use of artificial intelligence.

Among the system users are the Administration of the Russian President, the institute of President’s Representatives in Federal Districts, the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, the National Antiterrorism Committee, the Russian Ministry of Defense. The system’s database includes over 25 mln. entries. It has information on 90 thousand media, 220 thousand NGOs, 3.2 thousand Cossack organizations, 2.1 thousand communities of the small-numbered indigenous peoples (data as of 2018).

It should also be noted that no such indigenous peoples’ registries exist in international practice. The only similar local population registry was created in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China (earlier Eastern Turkistan) populated by the Uyghurs, a Turkic-speaking people belonging to the Sunni branch of Islam.

Source – iRussia

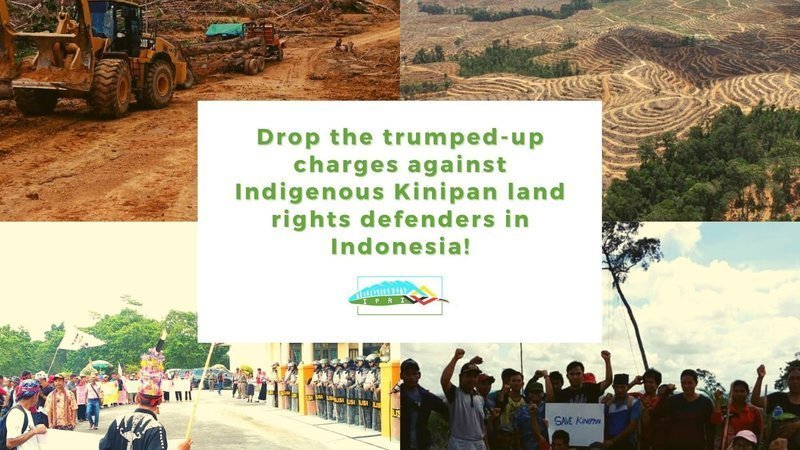

Drop the trumped-up charges against Indigenous Kinipan land rights defenders in Indonesia!

Amid the pandemic, six Indigenous villagers, including Kinipan community leader Effendi Buhing, and two Indigenous youth, were arrested by the Central Kalimantan Police, in Indonesia, for defending their customary forest against the expansion of PT Sawit Mandiri Lestari (PT SML), a palm oil company. Buhing was arrested on August 26, while the other five were arrested on August 15.

All of them were released, but are now facing criminal charges for the alleged theft of chainsaw owned by the palm oil company. This chainsaw was confiscated by the villagers to stop the PT SML from further destroying their customary forest.

Indigenous Peoples Rights International (IPRI) and Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara – AMAN (National Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of the Archipelago – Indonesia) strongly condemn these recent arrests and criminalization of the Kinipan villagers, which violates their internationally recognized right to their lands, territories, and resources.

The unwarranted act by the police was in retaliation to the protest actions and growing resistance of Kinipan villagers against the forcible eviction from their lands by palm oil company.

In response to the encroachment of PT SML into Laman Kinipan customary territories, the community registered their customary territories to the Customary Territory Registration Agency in March 2017. A certificate for the land was also given to the Laman Kinipan Indigenous Peoples community on July 27, 2017.

According to AMAN, the Laman Kinipan community found out that their forest was being taken over by PT SML in April 2018. Consequently, the community imposed customary sanctions against the company after it destroyed their customary territory, and filed complaints to the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, National Human Rights Institution Komnas HAM, and the Office of the Presidential Staff (KSP).

The complaints of the Laman Kinipan people are yet to be acted upon. However, when PT SML filed unwarranted charges of theft against Indigenous leader Buhing and the other five villagers, the police were quick to make the arrest and file the charges.

The arrest of Kinipan Community Leader Buhing clearly shows the double standards of the police forces. The arrest is used as a tactic to criminalize legitimate dissent so as to push for the illegal operations of PT SML into Laman Kinipan Indigenous Peoples customary lands. This tactic is being used globally to silence Indigenous Peoples in the face of the onslaught against their rights.

Even during Covid-19 pandemic, several Indigenous Peoples communities have become targets of criminalization and violence to give way to the operations of large-scale projects involving agribusiness and extractive industries.

If PT SML will have its way, 190, 000 hectares of forest will be lost; thereby reducing one of the biggest rain forests in Southeast Asia and causing severe damage to climate, biosphere, and ecosystem.

Laman Kinipan Indigenous Peoples have long been protecting their forest and environment from total destruction, yet they constantly face threats and violence, arrests and detentions, and criminalization for defending their lands, forests, and territories.

We call on President Joko Widodo, the Minsitry of Environment and Forestry, Ministry of Agrarian and Spatial Planning, the Indonesian Parliament, and the Indonesian Police:

- To drop the trumped-up charges against Kinipan community leader Effendi Buhing and the other five villagers, and to ensure their safety against any further attacks;

- For the police and the PT SML to stop the criminalization of Indigenous peoples for their legitimate actions to protect their right to their customary forest;

- For the Ministry of Environment and Forestry to revoke Decree on Forest Release for PT SML;

- For the Ministry of Agrarian and Spatial Planning to revoke the concession of PT. SML in Laman Kinipan’s territory;

- For the immediate and proper implementation of the Constitutional Court decision number 35/2012 to recognize customary territory in accordance with the provisions of the 1945 Constitution; and

- For the Indonesian Parliament to enact the law on the rights of Indigenous Peoples to ensure the full implementation of the provisions contained in the 1945 Constitution and the the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

If you are interested to be a signatory, please sign on this petition or send your FULL NAME, TITLE/POSITION, and ORGANIZATION/AFFILIATION to ipri@indigenousrightsinternational.org or IPRIsecretariat@gmail.com.

You can sign on as an organization or as an individual, please indicate which options you are amenable to. Sign ons will close on September 15, 2020 at 16:00 (GMT +7), 05:00 (EST), 02:00 (PST), 17:00 (GMT +8).

NOTE: You are not required to donate to this petition.

(Photo credit: Laman Kinipan Community)

The dirty secret behind your ‘green’ electric car

The automotive industry is driving growing demand for nickel, critical for batteries, despite the pollution that production can cause.

MARINE RESCUE SERVICE/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

As Tesla shares continued their stellar rise last month, a group representing indigenous communities in Russia sent a letter to Elon Musk.

“We are respectfully requesting that you DO NOT BUY nickel, copper and other products from the Russian mining company Nornickel,” they told the billionaire boss of the electric carmaker.

Citing the huge diesel spill from a Nornickel plant that turned Siberian rivers crimson this summer, they alleged that the world’s leading high-grade nickel producer was “a global leader in environmental pollution” and urged Tesla to rule out buying from the miner until it cleaned up its act.

The letter came in response to a striking plea that Mr Musk had made to mining companies weeks earlier. “Wherever you are in the world, please mine more nickel,” he said. “Tesla will give you a giant contract for a long period of time if you mine nickel efficiently and in an environmentally sensitive way.”

While concerns over child labour and corruption in mining cobalt for electric vehicle batteries are well-documented, Mr Musk’s comments have focused attention on the less-scrutinised market for nickel. The metal is every bit as critical for batteries — and presents its own concerns for ethically minded electric vehicle buyers.

Nickel is used in most lithium-ion batteries; it helps to provide higher energy density and to improve storage capacity. Today, batteries account for only about 7 per cent, or 150,000 tonnes a year, of global nickel demand, according to Wood Mackenzie; most nickel is still used to make stainless steel. However, the energy and mining consultancy expects battery demand to increase to 650,000 tonnes by 2030, helping to drive total nickel demand to 3.2 million tonnes a year, from 2.3 million tonnes at present.

Andrew Mitchell, head of nickel research at Wood Mackenzie, argues that the market is in fact oversupplied now and he does not “see a particular squeeze on the availability of materials” to meet growing demand. However, “if you then start to want to look at the ESG [ethical, social and governance] issues around your nickel, then that might start to pose you problems”.

Nornickel could increase its production of battery-grade nickel in Russia substantially, but doing so would depend on it first securing long-term contracts with customers.

As for Nornickel’s own environmental record, Andrey Bougrov, head of environmental protection at the miner — which is facing a $2 billion fine over the diesel spill — said that the clean-up campaign was “in full swing”. He insisted that the company was “committed to environmentally sensitive production of metals”, was investing large sums in reducing hazardous emissions, but was “dealing with factories built in the Soviet times when architects largely ignored environmental aspects of the production”.

For environmental groups, it is paramount that such concerns are addressed. “The clean energy transition cannot be underpinned by dirty mining. It’s sort of its Achilles’ heel,” Payal Sampat, mining programme director at Earthworks, said.

The Saami Council supports appeal from indigenous leaders regarding NorNickel

The Saami Council supports the appeal from indigenous leaders and experts of the Russian Federation to Mr. Elon Musk and Tesla, to refrain from buying nickel from NorNickel until the company implement indigenous peoples’ rights and fulfill its environmental obligations.

A sustainable future requires responsible industry and business, and the development of so-called sustainable solutions cannot happen on the costs of indigenous peoples and the environment. Then it is no longer a sustainable solution.

The Russian company NorNickel is a global leader in the production of the mineral nickel. Murmansk Oblast and the Taymyr Peninsula has been the homeland for indigenous peoples of the Arctic for generations, and are the principal sites for the company’s activities. The Sámi, Nentsy, Nganasan, Entsy, Dolgan, and Evenki communities have preserved the traditional life, culture, and economy of Northern peoples, including reindeer herding, hunting, fishing, and gathering. Healthy and productive ecosystems, both on land and water, are the basis of indigenous peoples’ culture and identity. Indigenous peoples’ survival and existence must be secured and strengthened through the sustainable management of natural resources. Companies must be held accountable for cleaning up after accidents and pollution, also after ended activity.

Free, prior and informed consent (FPIC ) is a principle enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP, which establishes a universal framework of minimum standards for the survival, dignity, and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world, and it elaborates on existing human rights standards and fundamental freedoms as they apply to the specific situation of indigenous peoples. This principle must apply to all industrial activities taking place on indigenous land and FPIC must be included in the code of conduct of any company.

‘The Fish Rots From the Head’: How a Salmon Crisis Stoked Russian Protests

OZERPAKH, Russia — A row of stakes hundreds of feet long pokes out of the endless estuary of the Amur River on Russia’s Pacific coast, resembling the naked spine of a giant fish.

It is a piece of commercial fishing infrastructure reminding the people who still live here that nature’s wealth — in this case, millions of chum and pink salmon — belongs to the well-connected few.

“It’s as though they must exterminate these riches, mercilessly,” says Galina Sladkovskaya, 65, waiting in vain for a fish to bite at a levee about 20 miles upstream. “They only need money and nothing else. They don’t have a human soul.”

Along the Amur, one of Asia’s great waterways, Russians feel cheated, lied to and ignored. The wild salmon fishery that they once took for granted is gone, they say, because Moscow granted large concessions to enterprises that strung enormous nets across the river’s mouth.

People’s anger over their depleted fish stock is so widespread that it has been a driving force behind the anti-Kremlin protests that have been shaking the Far Eastern city of Khabarovsk, on the Amur, since early July.

“This was a gesture of people desperate to be heard,” Daniil Yermilov, a Khabarovsk political consultant, said of the protests. “People wanted to live how they used to live, so that they can catch fish again.”

The story of the Amur’s vanishing salmon also sheds light more broadly on why President Vladimir V. Putin’s popular support has fallen close to the lowest point of his 20-year rule.

Russians’ turn away from Mr. Putin revolves less around abstract concepts of freedom and geopolitics than the concrete instances of poverty and injustice they see in their daily lives — and the feeling that the country’s elite neither knows nor cares about their struggles.

On a dirt road recently near the Amur’s mouth, a green truck splashed by before Leonid, a fisherman, whistled the all-clear. Two boys, his sons, hustled out of their hiding spot in the reeds, dragging a sack of glistening salmon.

“We’re being forced to become poachers,” he said, cursing and refusing to give his last name because he was in the process of breaking the law. “What is Putin thinking?”

Residents say there is virtually no way for them to legally catch enough to eat of what little fish remains, amid ever-tightening regulations on recreational and Indigenous fishing.

The boards tied to the roof of Leonid’s aging blue hatchback were meant to provide an alibi — he was just out collecting wood scraps. His rear windshield carried the slogan of the Khabarovsk region’s summertime political awakening: “I Am/We Are Sergei Furgal.”

Sergei I. Furgal, a former scrap-metal trader, ran for governor of the sprawling Khabarovsk region in 2018 and beat the incumbent, a Kremlin ally, in a rare upset. He gained popularity with populist moves unusual in Russia’s top-down system of governance: He cut his salary, improved school lunches and held frequent listening tours, skipping the tie and posting copiously to Instagram.

By then, the Amur’s fish crisis was already brewing. Federal authorities had granted expansive salmon fishing rights to companies that installed huge, stationary nets in the estuary and at the river’s mouth.

In the fall, the legions of migrating salmon used to make it hundreds of miles upriver to Khabarovsk, filling apartment refrigerators with smoked fish and cheap salmon roe — a New Year’s Eve staple that Russians call red caviar — sold by the kilogram.

The catch topped out at 64,000 metric tons in 2016 but then dropped precipitously, to 21,500 metric tons in 2018, the World Wildlife Federation says. And few salmon made it to Khabarovsk or the spawning grounds on the Amur’s tributaries.

“People here right now can’t catch enough to put on the table, while commercial fishermen reap huge profits,” Mr. Furgal said soon after taking office. “We’re going to try to change this state of affairs.”

He called for new limits on commercial fishing, some of which were implemented, but the salmon have remained scarce. Then, early last month, a SWAT team from Moscow pulled Mr. Furgal out of his black S.U.V. and spirited him onto the eight-hour flight back to the capital.

He was accused of masterminding murders some 15 years ago, but Khabarovsk residents saw a naked Kremlin attempt to remove a maverick governor more loyal to his constituents than to Mr. Putin. Two days later they spilled into the streets in the tens of thousands in the biggest protests Russia’s regions had seen since the fall of the Soviet Union.

The protests, now in their second month, are driven by regional pride, economic frustration and fatigue with Mr. Putin. But their animating emotion, dozens of interviews across the region showed, was a sense of injustice, as encapsulated by the fish crisis: Salmon had been part of life here for generations, and now Moscow had taken it away and offered nothing in return.

“Putin only thinks about war and about his pockets,” said Andrei Peters, 53, a small-business man in the impoverished village of Takhta on the lower Amur. “No one thinks about the people.”

In the struggling fishing village of a few hundred people with no regular internet or road connection to the outside world, someone had printed out black-and-white Furgal posters on regular sheets of paper and affixed them to the wooden electricity poles. With their now ex-governor behind bars, residents said they feared they had lost the one person in power who heard their concerns.

Indeed, the few officials in the region who agreed to interview requests in the wake of Mr. Furgal’s arrest either dismissed their constituents’ fish-related anger or redirected the blame away from the Kremlin. In the Indigenous community of Sikachi-Alyan, an hour’s drive outside Khabarovsk, the village head, Nina Druzhinina, explained that “America is at fault for all of our sins.”

“The C.I.A. has inserted its services everywhere, and its spy network is probably highly developed,” Ms. Druzhinina said. Commercial fishermen were able to exploit the Amur River, she said, because of post-Soviet Russia’s American-inspired legal code.

In the regional parliament, the speaker, Irina Zikunova, said that many Khabarovsk residents “are guided by impulse, are guided by emotions, are guided by feelings” rather than by facts. She rejected the notion — heard virtually universally in interviews with residents along the Amur — that officials in Moscow had shaped fishing regulations to the benefit of well-connected businesspeople.

“In reality, this is a made-up problem,” she said.

One of the Amur’s main fishing magnates, Aleksandr Pozdnyakov, is chauffeured around Khabarovsk in a black Mercedes Maybach. He acknowledged in an interview in his tastefully dark-toned office that the Amur fishery is in crisis. But he said the problem was overfishing by local residents who preferred to “pay nothing and do nothing while catching as much as they want.”

Mr. Furgal, the Khabarovsk governor arrested last month, made things worse, he said, speaking “as though he’s doing everything for the people” and telling the public they had a right to the salmon in the Amur.

“I’ll tell you one thing,” Mr. Pozdnyakov said of the tens of thousands protesting in support of Mr. Furgal, “I am confident that practically 99 percent of those going out are slackers who don’t want to do anything.”

Experts say there is truth to the notion that poaching by local residents is part of the problem. Olga Cheblukova, who coordinates the World Wildlife Fund’s Amur River studies, said the environmental group’s researchers have seen hundreds of dead salmon scattered near their spawning grounds, their bellies sliced open and their roe removed.

The fundamental issue, she said, is poor federal oversight that failed to detect a natural decline in the wild salmon population after the large catch in 2016. In the years that followed, regulators granted fishing quotas exceeding the actual migrating population, allowing runs of salmon to be virtually exterminated before they managed to reproduce.

In the fall of 2018, W.W.F. researchers counted an average of about 0.1 chum salmon per 1,000 square feet of river at their spawning grounds, compared to a norm of about 50.

To Khabarovsk residents, that failure of governance means more expensive fish — a parable for all of Russia, where official mismanagement and corruption often translates to bad roads, crumbling hospitals and polluted wilderness.

The protests in Khabarovsk show how easily public anger over those failures can now boil over — as it did for Evgeny Kamyshev, 32, a protester who blamed the Kremlin for the scarcity of salmon.

“The fish rots from the head,” he said.

Oleg Matsnev contributed research from Moscow.