Canada’s 1st Indigenous coast guard auxiliary has launched in B.C.

Indigenous members bring extensive knowledge of their territorial waters, says auxiliary director

First Nations along B.C.’s West Coast have a long history of responding to emergencies in the Pacific.

Now, more than four years since it was announced, the Indigenous Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary has fully launched in B.C. — already having completed a number of missions.

The auxiliary consists of 50 volunteer members from five First Nations along B.C.’s coast — the Ahousat, the Heiltsuk, the Gitxaala, the Nisgaa and the Kitasoo.

Tuesday evening, the auxiliary was dispatched to a call in Bella Bella, where someone was in the water. The mission was a success.

“Luckily, the person was found safe and sound,” said Conrad Cowan, the executive director of the auxiliary.

“Here we are, right into the fray already.”

Cowan says the auxiliary will now work in tandem with the Canadian Coast Guard, responding to remote areas that would take the Coast Guard a long time to attend.

As well, he says the Indigenous mariners who have now joined the auxiliary have a wealth of knowledge of their territorial waters.

Cowan admits, even with his extensive background as a Search and Rescue technician with the military, sometimes his skills don’t compare, especially when it comes to navigating the waters and whirlpools along the coast.

“They are extremely accomplished,” he said, speaking with All Points West host Kathryn Marlow. “They’ve been doing this for a very long time. They know the waters.”

And as the man in charge, Cowan has no complaints.

“It really does make my job easy, doesn’t it? I just have to keep the lights on and get the equipment to them.”

The volunteer members have also been provided with proper training, equipment and certification for their community boats. He says brand new Search and Rescue boats are also being built thanks to government grants.

And, fortunately for those travelling up and down the coast, Cowan believes this is only the beginning for the auxiliary, which he hopes to one day expand to other First Nations.

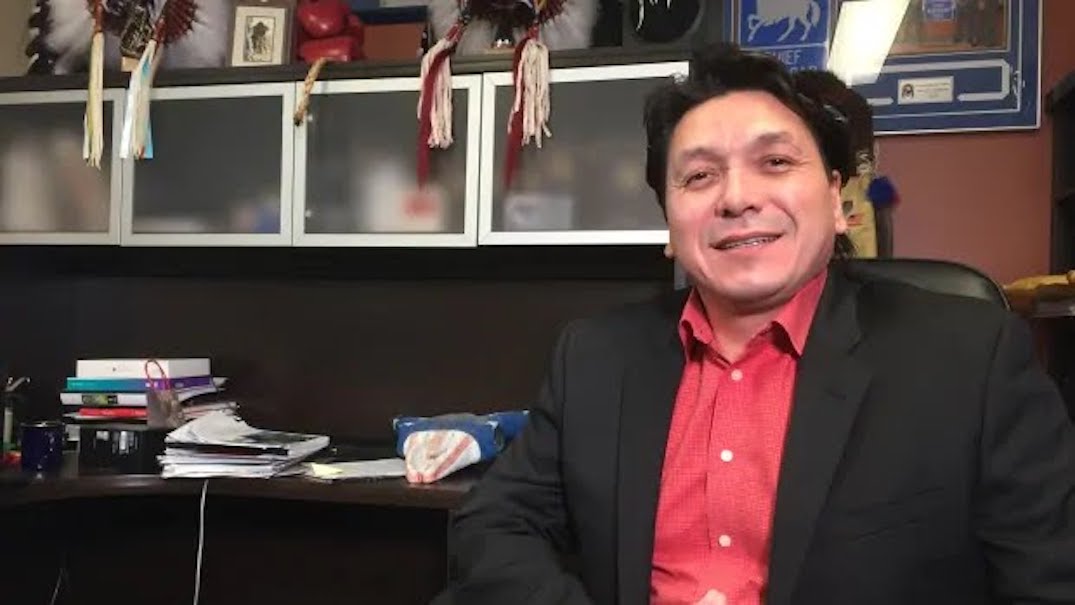

Chief Darcy Bear appointed to Order of Canada

Chief Darcy Bear has been appointed to the Order of Canada.

He is one of the 114 appointments announced by the governor general on Friday.

Bear is being recognized for his “visionary leadership of the Whitecap Dakota First Nation, and for creating economic and social development opportunities for his community.”

He was reelected as chief for an eighth consecutive term in 2016. Whitecap is located 26 kilometres south of Saskatoon.

Some of the economic development projects that have taken place under Bear’s tenure include the development of the Dakota Dunes Casino, the Dakota Dunes Golf Links and the ongoing development of a light industrial park.

- Whitecap Chief Darcy Bear wins lifetime achievement award

- Whitecap Dakota First Nation signs framework agreement for treaty with Canada

- Economic development key to reconciliation, say First Nations leaders

As chief, he has also overseen the construction of a new elementary school and expanded public infrastructure, and brought in high speed internet and new housing for Whitecap.

Bear is also a member of the Saskatchewan Order of Merit and won the 2016 Aboriginal Business Hall of Fame Lifetime Achievement Award.

The latest Order of Canada list also includes Alfred Slinkard, from Saskatoon. He is being recognized with an honorary appointment for his research in agronomy. He developed two cultivars of lentils that the government says transformed agriculture in western Canada and now feed thousands of people.

Russia’s technical agency says melting permafrost did not cause summer oil spill in Arctic

Russia’s technical oversight agency has said that last summer’s massive spill of diesel fuel into the waters of northern Siberia, which was widely blamed on melting permafrost, was instead caused by a poorly maintained reservoir riddled with technical faults.

The reservoir, owned by a subsidiary of the giant Norilsk Nickel, gave way on May 29, spilling 150,000 barrels – or 20,000 tons – of fuel, sullying the Ambarnaya River near the city of Norilsk and constituting one of the worst industrial accidents ever to take place in the Arctic environment.

Vladimir Putin declared a state of emergency and Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office launched a wide-reaching investigation of industrial sites located in Russia’s sprawling permafrost environment to check for weaknesses due to melting. At the time, Norilsk Nickel’s chief executive, Vladimir Potanin, suggested that thawing tundra was the most likely culprit in the spill.

But the report released this week by Rostekhnadzor cited faulty construction of the collapsed tank and the poor maintenance practices followed by its owner, the Norilsk-Taimyr Energy Company, or NTEK, run by Norilsk Nickel.

Primary in Rostekhnadzor’s conclusions was that foundations under pilings holding up the reservoir weren’t strong enough to support the fuel tank. The agency also blamed NTEK for not performing required maintenance. Rostekhnadzor based its findings on interviews with employees, technical documentation and numerous visits to the site of the accident, the agency’s report said.

Rostekhnadzor’s findings are in line with what many Russian environmentalists had suspected in the aftermath of the accident. Speaking in June during a Bellona-hosted live-stream discussion on Instagram, Alexei Knizhnikov of the Russian branch of the World Wildlife Fund, said the condition of the ruptured tank made the accident predictable.

“This accident could have been prevented,” he said. “The cause of the accident was a completely outdated tank, which is not even visually monitored by environmental safety systems”

Indeed, an investigation by Novaya Gazeta, a respected independent newspaper in Russia, found that the poor state of the tank had been known to officials at Norilsk Nickel as far back as 2016, when the company considered replacing them.

Still, environmentalists and many in the Russian government agree that thawing tundra caused by dramatic temperature rises in the Arctic region poses major threats to extensive Russian infrastructure. Last year, the Arctic experienced its warmest winter on record. That was followed in April and May by a heat wave, with May seeing temperatures between 3 degrees Celsius and 6 degrees Celsius above average since January. More recently, vast portions of Arctic oceans that usually freeze over by this time of year have not.

Meanwhile, some 65 percent of Russia’s landmass is covered by a pack of soil and ice that, until recently, has remained permanently frozen. According to Rosgidromet, Russia’s federal weather service, these spiking temperatures are causing permafrost to thaw in certain areas, a trend the agency says puts some $300 billion worth of buildings and infrastructure at risk.

Among that infrastructure are more than 75,000 kilometers of oil pipelines stitched across Siberia, which the agency said could become vulnerable to ruptures as the frozen soil beneath them begins to retreat.

Also included are entire industrial mining, gas and oil centers – as well as the highways and railways that lead to them and towns that have sprung up around them. In Norilsk alone, said the agency, permafrost has retreated by 22 percent.

The newly unstable ground is already taking its toll. Over the past 10 years, said the report, more buildings in Norilsk have collapsed because of subsidence than in the previous half century.

Arctic melt only contributes to climate change. As permafrost thaws, it releases vast stores of carbon dioxide – the gas most responsible for global warming – which drives up temperatures even more.

According to the Arctic Report Card 2019, a study conducted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in the United States, the permafrost environments of Siberia, Alaska, Greenland and Canada are thought to contain as much as 1,460 to 1,600 billion metric tons of organic carbon, which converts to carbon dioxide as it thaws.

The report states that, because of this melting process, the Arctic is now contributing some 1.1 billion to 2.2 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide annually to the world’s atmosphere. That’s equal to the yearly carbon contribution of countries like Japan, on the lower end, and to Russia itself, on the higher end.

Harmful algae bloom behind mass die off of marine animals in Russia’s Far East, scientists say

Scientists have determined that a mysterious die-off of marine animals off the coast of Kamchatka in Russia’s Far East earlier this month was caused by a harmful algae bloom, officially laying to rest theories that a manmade chemical spill was to blame, Russian media have reported.

The comments, reported in RBC and other wire services, come from Andrei Adiyanov, vice president of the Russian Academy of Sciences, who said that thousands of water samples pointed to toxins from a particular single-celled organism called a dinoflagellate.

“We can say that the mass death of benthic aquatic organisms occurred as a result of exposure to toxins from a complex of species of the genus Karenia, a representative of dinoflagellates,” he was quoted as saying.

The announcement comes after weeks of uncertainty during which masses of dead sea creatures washed up on local beaches, driven by a foul smelling and murky tide. The grizzly finds, first reported by surfers Kamchatka, seven time zones to Moscow’s east, exploded across social media platforms as local residents documented their discoveries and demanded accountability.

Early investigations by environmentalists cited high petroleum levels and other pollutants in the water. Local officials also suspected the mass animal die off might be tied to leaks of highly toxic rocket fuel, which is bunkered at a number of Far Eastern military facilities, often in shabby conditions.

The new findings from the Russian Academy of Sciences, however, dismisses those theories, after scientists with the organization observed large appearances of phytoplankton, some several hundred kilometers wide, massing off Kamchatka’s coast.

According to Mikhail Kirpichnikov, head of Moscow State University’s department of bioengineering, and a member of the academy, groupings of plankton were observed drifting northward toward Chukotka before shifting direction to the south to the shores of Kamchatka. It was these microscopic organisms that fed the harmful algae bloom, he said.

Harmful algae blooms occur when colonies of algae— which are simple plants that live in the sea and freshwater — grow out of control, pro ducing toxic or harmful effects on people, fish, shellfish, marine mammals, and birds.

While there are many factors that may contribute to these blooms, how these factors come together to create a bloom of algae is not well understood. Studies indicate that many algal species flourish when water circulation is low and water temperatures are high.

The blooms can last from a few days to many months. After a bloom dies, the microbes which decompose the dead algae use up more oxygen, which can lead to die offs of fish and other marine organisms. When these zones of depleted oxygen cover a large area for an extended period of time, they are referred to as dead zones, where neither fish nor plants are able to survive.

Harmful algae blooms have been increasing in size and frequency worldwide, a factor that many scientists attribute to climate change.

Should this be the case, then the mass marine die off that has gripped Kamchatka since late September is only the latest disaster Russia can attribute to warming global temperatures. n May, near the northern Siberian city of Norilsk, a fuel tank resting on thawing permafrost collapsed, spilling 20,000 of diesel oil into area waterways and causing a local river to run crimson.

Svetlana Radionova, a representative of the Kamchatka division of Rosprirodnazor, Russia’s environmental oversight agency, also cast doubt on pollutants being the cause of the mass sea animal die off.

To date, we have conducted almost five thousand studies, taken hundreds of samples, and all these studies indicate that we do not see a pronounced man-made impact on the habitat of aquatic organisms,” she said, according to Russian media.

Alexei Ozerov, director of the Institute of Volcanology and Seismology at the Far East Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, said studies on the harmful algae bloom will continue.

“Next, one of the main tasks is to conduct sea expeditions and figure out what can bring these algae into such an active state that we have these blooms,” he said.

How far can President-elect Joe Biden go to salvage US climate efforts?

Joe Biden, the projected winner of the US presidency, plans to restore dozens of environmental rollbacks enacted by the administration of Donald Trump and launch the most ambitious climate agenda ever forwarded by an American president. Though his most progressive policies will face pushback from Senate Republicans and conservative attorney’s general, the White House, with Biden in charge, plans to make a complete turnaround on US climate policy.

As early as Saturday afternoon, after major television networks called the presidential contest for Biden, the president-elect’s transition team posted its climate strategy online, pledging on “day one” to re-enter the Paris climate accord – from which the Trump administration formally withdrew on Wednesday, the day after the election.

The efforts will include restricting oil and gas drilling on public lands and waters; jacking up federal mileage standards for cars and trucks; blocking fossil fuel pipelines across the country; providing federal incentives for renewable power development; and urging other nations to cut their own carbon emissions.

In a victory speech Saturday night, Biden identified climate change as one of his top priorities as president, saying Americans must marshal the “forces of science” in the “battle to save our planet.”

The Biden climate plan looks to eliminate carbon emissions from the electric sector by 2035 and to spend nearly $2 trillion in investments ranging from weatherizing homes to building a robust electric car charging infrastructure throughout the country.

Nevertheless, the new administration will be starting out on the back foot. The US is the world’s biggest economy and second biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, but Trump Administration reversed measures taken by Barack Obama to reduce those emissions and rejected the Paris Agreement, which binds nations to hold global heating to well below 2C, with an aspiration to limit temperature rises to 1.5C.

Runoff races in Georgia scheduled for January will determine whether the US Senate will be receptive to a climate friendly legislative agenda. Should Democratic challengers in those elections fail, Biden may have to rely on a combination of executive actions and more-modest congressional deals to sidestep Republican opposition. His room to maneuver could be hamstrung further by a conservative majority on the US Supreme Court when his plans meet the inevitable legal challenges.

Voters want climate action

But smart climate policy may not be as hard to sell as it was when Trump took office in 2017. US Voters have begun to experience the effects of climate change firsthand and polls take over the summer show that two-thirds of Americans – including a majority of Republicans — say they want the government to do more on climate change. Since then, record-setting wildfires and droughts have ravaged the West Coast while states from Texas to Florida are reeling from a hyperactive hurricane season that has yet to end.

And in an economy reeling from the effects of the global coronavirus pandemic, Biden has argued that curbing carbon emissions will create high-paying jobs.

Achieving much of this in when political divisions still run hot will be difficult – but not impossible – without Senate approval. Environmental groups in the US have published extensive lists of which policy moves Biden can make as soon as inauguration day – all without having to wrangle congressional support.

Unwinding Trump Rollbacks

Among those actions is wielding the extensive powers of executive orders – a power Trump used to enact many of his environmental rollbacks. The Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in New York tracked 159 Trump-era actions that cut back on environmental protections or promote the use of fossil fuels or both. In August, the center published a blueprint on how to unwind those changes under a Democratic administration.

Aside from rejoining the Paris accord – which requires the US to submit new commitments for reducing the nation’s emissions – Biden can quickly issue executive orders that would reverse a slew of Trump rollbacks. For instance, Biden can reverse Trump’s much-heralded “America First” energy strategy aimed at opening United States coastal waters to oil and gas drilling. He can also reverse Trump’s reversal of an Obama policy that directed federal agencies to cut their own greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent.

Further, he can also instruct his own Environmental Protection Agency – now in the hands of fossil fuel lobbyists appointed by Trump – to develop a more ambitious version of Obama’s Clean Power Plan for the electricity sector to further his goal of hitting net-zero emissions by 2035. He can also compel the Department of Transportation to develop, as his climate plan promises, “rigorous new fuel economy standards aimed at ensuring 100% of new sales for light- and medium-duty vehicles will be electrified.”

On top of all that, a crucial structural move Biden can make without congress is using the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation to ensure that the Federal Reserve – and the financial system more broadly – takes climate risk into account and channels investment away from carbon-intensive projects.

Most importantly, the Biden administration can reassure the world that the United States is back to taking climate change seriously. As president, his foreign policy powers are virtually limitless. Rejoining Paris is merely the first step.

The limits of executive power

Of course — just as Obama and then Trump have seen — executive action is subject to legal challenge, and Biden will face not just a Supreme Court, but an entire federal judiciary stacked with more conservative appointees, many of whom favor deregulation. Even if Biden’s policies survive that, they could again be reversed by a future president.

Still, Biden can make enormous progress in four years, especially if he is fearless in his use of executive actions – and those actions are likely to find support from many quarters of energy industry itself. Pressured in part by consumer demand, a number of utilities have set their own zero-carbon goals, and some oil companies vow to invest more in renewables. A growing list of major companies, along with cities and states, are also setting aggressive targets for carbon neutrality.

But after four years of the Trump administration there is much ground to make up – and nothing Biden can do can make up for lost time.

During the Trump years the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has issued increasingly urgent warnings, saying that the window to hold off the worst climate change is closing. Many researchers consider Trump’s failure to address the issue to be the greatest harm he inflicted on the environment. That presents the Biden administration with its greatest environmental challenge.

Haaland being vetted by Biden team for Interior secretary

The Biden transition team is in the process of vetting Rep. Deb Haaland (D-N.M.) for the Interior secretary post, sources told The Hill on Tuesday.

The development came after Haaland dropped out of the three-way leadership race for House Democratic Caucus vice chairwoman.

If Haaland is tapped by President-elect Joe Biden, her nomination would be historic, making her the first Native American Cabinet secretary, where she would oversee an agency with vast responsibility over tribal issues and public lands. In 2018, she became one of the first two Native American women elected to Congress, alongside Rep. Sharice Davids (D-Kan.).

More than half of the president-elect’s transition team is comprised of women, and nearly half of its members are people of color; Biden has also vowed that his new Cabinet and administration will be very diverse and “look like America.”

Haaland, the former chairwoman of the New Mexico Democratic Party who just won reelection to the House, did not respond directly when asked why she suddenly dropped out of this week’s leadership race.

“We have an opportunity to unify our caucus, plan for the future, and support working families while we’re facing the challenges that have come from an administration who didn’t take this pandemic seriously,” Haaland said in a statement.

“I’ve deeply appreciated this process — discussing priorities, getting to better know my colleagues, and their districts and issues, and also answering questions about Indian Country. I look forward to continuing these conversations with a united caucus, laser-focused on healing and rebuilding our country,” she added.

Haaland, 59, has previously expressed interest in the role. In an interview with HuffPost last week, Haaland said “of course” she was interested in leading the Interior Department.

The Biden transition team did not immediately respond to a request for comment, and it is not clear if it is also vetting other candidates. Other names being considered to lead the Interior Department include retiring Sen. Tom Udall (D-N.M.), whose father was Interior secretary in the 1960s, and Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.).

The vetting process includes a review of personal, financial and medical information, one source said, helping the Biden team spot any red flags.

Udall’s office suggested he is still being weighed for the role but did not say whether he is also being vetted.

“Deb Haaland is a close personal friend and I’ve been proud to work with her in Congress and long before that. Senator Heinrich has been an incredible partner and friend in the Senate for the past eight years. Like so many New Mexicans, I’m excited about the vision of the incoming Biden-Harris administration and I am honored to be considered for an opportunity to continue my public service,” Udall said in a statement to The Hill.

Haaland, who chairs the House Natural Resources subcommittee that oversees national parks, forests, and public lands, got a nod Monday from full committee Chairman Raúl Grijalva (D-Ariz.), who had been endorsed for the Interior role by the Congressional Hispanic Caucus (CHC). Grijalva, a progressive leader, backed Haaland while asking fellow CHC members to do the same.

“It is well past time that an Indigenous person brings history full circle at the Department of Interior. As her colleague on the Natural Resources Committee, I have seen first-hand the passion and dedication she puts into these issues at the forefront of the Interior Department from tackling the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women to crafting thoughtful solutions to combating the climate crisis using America’s public lands,” Grijalva wrote in the letter obtained by The Hill.

“It should go without saying, Rep. Haaland is absolutely qualified to do the job,” he added.

Biden this week began naming top staffers who will serve in the White House, including chief of staff Ron Klain and Rep. Cedric Richmond (D-La.), the Biden campaign’s national co-chairman, who will serve as a senior adviser to the 46th president and the director of the White House Office of Public Engagement.

Biden has yet to name any Cabinet members, though he could make some of those picks before Thanksgiving.

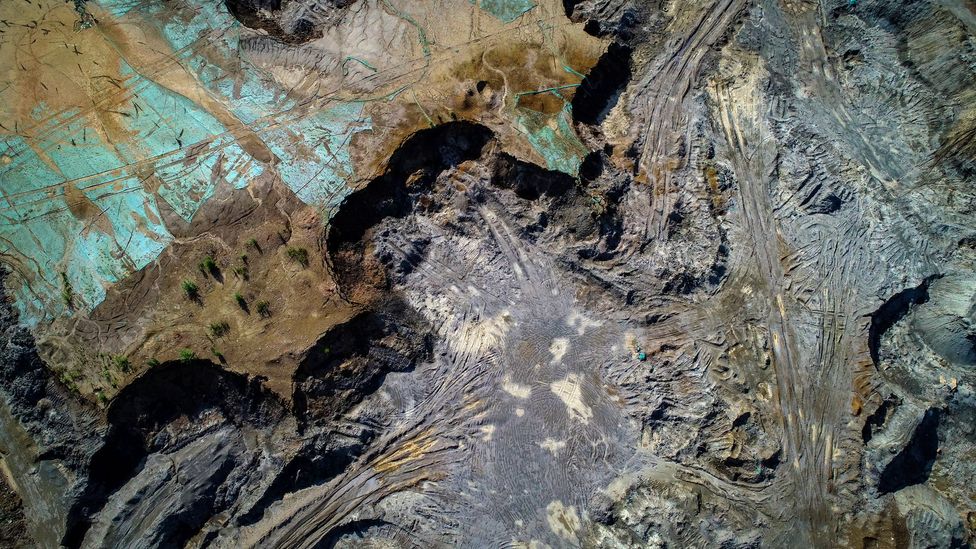

The scarred landscapes created by humanity’s material thirst

The world’s desire for electronics, fuel and geological riches is etched in devastating shapes and colours all over the globe. In the latest of BBC Future’s Anthropo-Scene series, we show the striking ways that mining has rewritten the surface of the Earth.W

When we dig to extract a precious metal, a carboniferous fuel, or an ancient ore, we remove a chapter of another time. Such materials are, in the words of the writer Astra Taylor, the “past condensed”, telling of epic eras of magmatic fury, tropical forests or hydrothermal steam. They take millions of years to settle or crystallise, then only moments to remove with machinery and explosive.

Ever since humans first realised that the ground beneath them held hidden riches, we have dug down to discover what lies beneath. Mining makes almost every aspect of our modern lives possible, and often the effects on the natural world are far, far away from home.

When you see the impact of a mine visually, it can subtly change how you think about your possessions. Even these words are delivered via geological materials – behind this screen, enmeshed in electronics, there are metals that were once locked for millennia within rock. And somewhere in the world right now, our desire for more and more this technology is fuelling ever-deeper and broader subterranean searches for those resources.

Below, we look at the myriad ways that mining has transformed the surface of the Earth – whether it’s the striking, unnatural hues of “tailings ponds” or the open-cast landscapes that look like the fingerprints of humanity itself. If the ancient ores and minerals we covet are the condensed past, then sadly what is in store is a scarred future.

Welcome to “Anthropo-Scene”, a new BBC Future series. By looking through a lens at far-flung places around the world, our goal is to compile a definitive photographic record of how humanity is reshaping our planet and nature.

One of the largest mining pits in the world, with 84 types of minerals, is the ‘No.3 pegmatite’ in Xinjiang, China (Credit: Shen Longquan/ Getty Images)

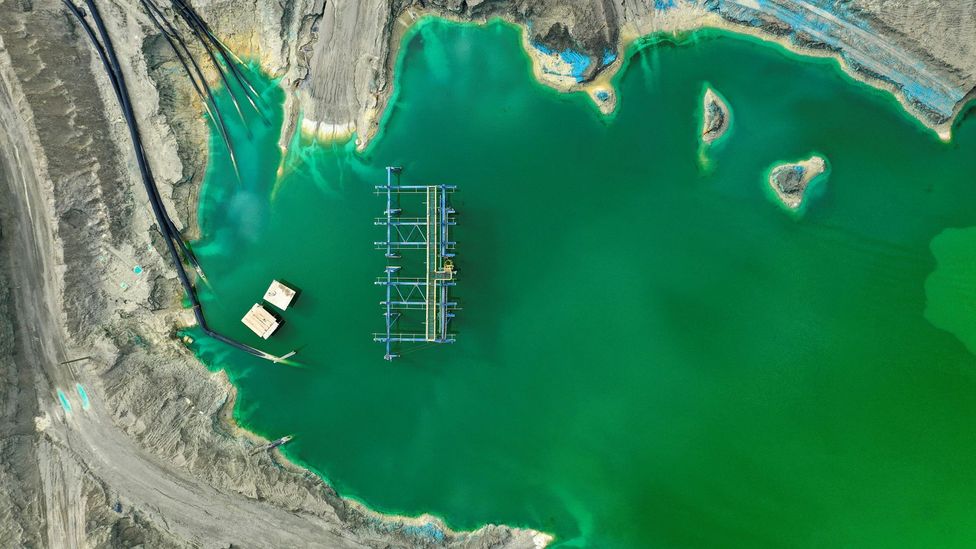

China’s Emerald Lake, in the Qinghai province, is an abandoned mining zone (Credit: Getty Images)

There, historic mining left behind salt and other minerals in giant ponds with a greenish hue (Credit: Getty Images)

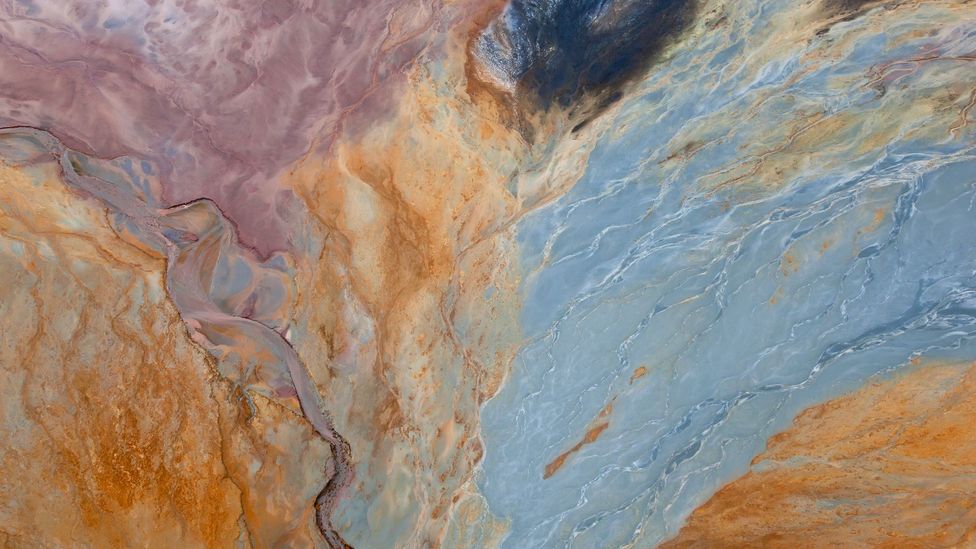

Oxidised iron minerals in the Rio Tinto mining area of Huelva province in Spain (Credit: Peter Adams/Getty Images)

Mixed with water, the iron minerals spread like watercolour paint across the landscape (Credit: Peter Adams/Getty Images)

When the minerals meet air, they redden, and then darken as they collect in deeper waters (Credit: Peter Adams/Getty Images)

The Carajas Mine in Brazil, one of the largest iron ore mines on the planet (Credit: Getty Images)

Like the whorl of a giant fingerprint: Bingham Canyon Mine, also known as the Kennecott Copper Mine, Utah (Credit: Getty Images)

The Los Filos gold mine in Guerrero State, Mexico (Credit: Ronaldo Schemidt/Getty Images)

In the Brazilian Amazon, the Esperanca IV informal gold mining camp, near the Menkragnoti indigenous territory Credit: Joao Laet/Getty Images)

Elsewhere in the Amazon, in Peru, a deforested area caused by illegal gold mining in the river basin of the Madre de Dios (Credit: Cris Bouroncle/Getty Images)

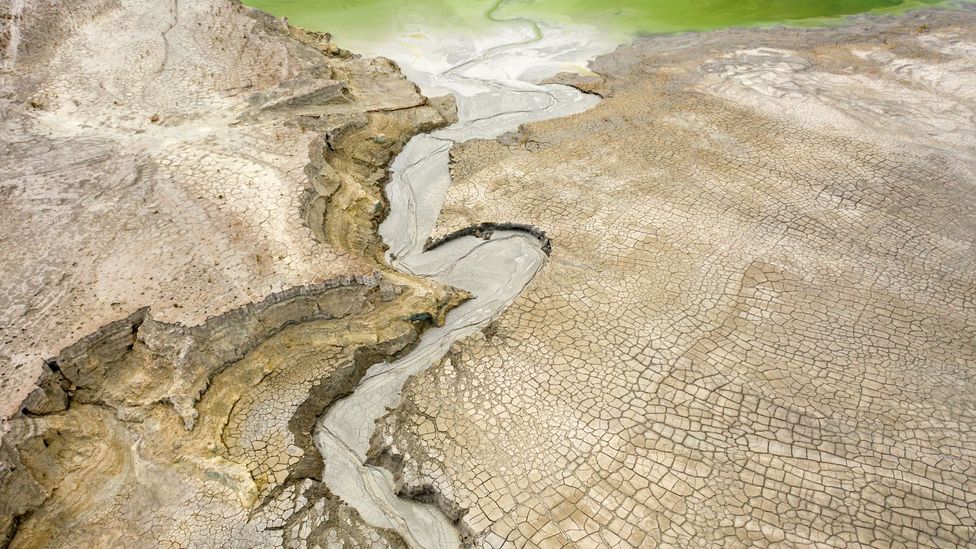

A tailings pond used to store byproducts of copper mining in Rancagua, Chile (Credit: Martin Bernetti/Getty Images)

Copper is one of Chile’s main exports (Credit: Martin Bernetti/Getty Images)

Cracks on a parched surface surround another tailings pond there (Credit: Martin Bernetti/Getty Images)

Away from the tailings, vehicle tracks weave around the Chilean copper mine (Credit: Martin Bernetti/Getty Images)

Orange water fans out over the forested landscape near a disused copper-sulphide mine near the village Lyovikha in the Urals, Russia (Credit: Sergey Zamkadniy/Getty Images)

Like the surface of another planet, the abandoned Khrustalny mine in Kavalerovo, Russia, which once produced 30% of the Soviet Union’s tin (Credit: Yuri Smityuk/Getty Images)

The Garzweiler opencast lignite coal mine in Juechen, Germany (Credit: Ina Fassbender/Getty Images)

Lignite coal is a soft fossil fuel made of naturally compressed peat (Credit: Ina Fassbender/Getty Images)

An open coal mine reaches to the horizon near Mahagama, in the Indian state of Jharkhand (Credit: Xavier Galiana/Getty Images)

The Eti Mine Works in Eskisehir, Turkey, where lithium – a key component of batteries – is produced from boron sources (Credit: Ali Atmaca/Getty Images)

Demand for lithium has risen as our demand for electronics and electric vehicles grows (Credit: Ali Atmaca/Getty Images)

The Rossing Uranium Mine in Namibia, one of the largest open pit uranium mines in the world, in the Namib Desert (Credit: Wolfgang Kaehler/Getty Images)

Like a jewellery pendant, a pond at an abandoned magnesite pit near Vavdos village in the mountains of Chalkidiki, Greece (Credit: Nicolas Economou/Getty Images)

The snowy Mir diamond mine in Russia hints at what our descendants may discover. What will they make of these legacies of our consumption? (Credit: Alexander Ryumin/Getty Images)

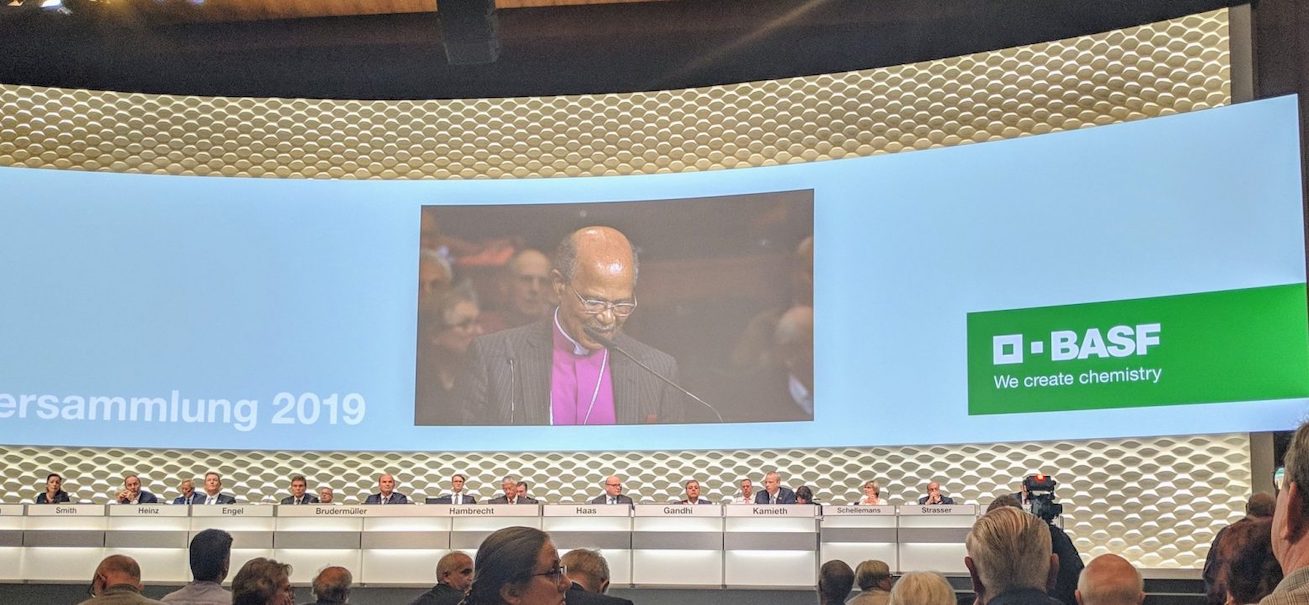

“We have hope”: Speech from Jo Seoka

Good morning and thank you for the opportunity to participate in your AGM. I am Johannes Seoka, former Bishop of the Anglican Church in Diocese of Pretoria in the Anglican Church of South Africa for 18 years. I am here representing and speaking on behalf of the Plough Back the Fruits Campaign constituted by South African, European and British network.

Last year Mr Bock cynically asked me not to come back this year. In fact, this is the major reason of being here today. I must say that though I was offended by his attitude, I decided to be forgiving and to be optimistic about our relationship for the sake of those who have entrusted me with the responsibility to speak on their behalf.

Chairperson, I now ask my interpreter to finish my challenge to you in the language most of us understand.

Dear Shareholders, Ladies and Gentlemen of the Management Board and the Supervisory Board, dear employees of BASF, Dear Ladies and Gentlemen,

My name is Isabelle Uhe, I am a member of the church relief organization charity Bread for the World, which has supported the concerns of the South African delegation from the very beginning. I will now present the speech of Bishop Seoka in German to you.

“This year we are here for the fifth time here at the Annual General Meeting in Mannheim with a delegation from South Africa on behalf of the international civic society campaign “Plough Back The Fruits” and speak on behalf of the workers in Marikana and their families. In Marikana are those mines, from which BASF obtains platinum, which is installed in catalysts.

For the past five years, we have been reporting on the unworthy inhumane living and working conditions in your platinum supply chain, about people whose salary is not enough to live on, let alone care for, families.

We told you about people who live in corrugated ironworks without electricity and water, as your contractor Lonmin still fails to meet its legal obligations to build houses and build infrastructure – not to mention the dignified treatment and fair compensation of those widows who lost their husbands in the Marikana massacre. In addition, many of the miners living there will lose their jobs soon after your platinum supplier Lonmin is taken over by Sibanye Stillwater. As a result of this acquisition, the second largest platinum producing group in the world will be created. BASF is still bigger 15 times that of Sibanye Stillwater.

We have always appealed to BASF to use its position as one of the largest chemical companies to send out a strong and clear message of change. For five years nothing has improved for the local people. In recent years, you’ve been talking to Lonmin, joining initiatives, or even initiating initiatives in the platinum sector on-site, attending conferences and discussions, and engaging with civil society actors, as you put it on your website, but, in the end, nothing has resulted in real improvements for the women, men and children on the ground.

For many years now, we and the people of Marikana have been kept waiting. Marikana, the place where BASF procures 2 million Euros a day in Platinum, the place where 34 miners died in 2012 while protesting for better living and working conditions.

Nevertheless, we are here again, Mr. Brudermüller, because we associate hope with you as the new CEO.

We hope for your support in the calls for a dignified life of people who mine the precious metal Platinum out of the African soil for you.

We hope that BASF will use the acquisition of your main supplier Lonmin by Sibanye Stillwater to establish transparent audits and monitor processes and re-set the supply chain relationship, for the better. A business relationship that can ensure what BASF is committed to. We hope you will support development secretary Mueller in his quest for protecting human rights in value chains. As a leading member of the Global Compact you surely want to be supportive of protecting human rights in business?

Especially now, as the public awareness is increasing and your neighbour France sets clear signs with its progressive law making for corporate responsibility. We hope that you will combine your quest to guarantee the supply of raw materials for Europe with the necessity to pay fairly for those. Only within a fair deal it can be ensured that the inequalities between North and South are reduced.

We appeal to you to honour your commitment to sustainable, responsible and fair business conduct along your supply chain. In this spirit of hope we are asking you:

With the take-over of Lonmin by Sibanye Stillwater we expect an acute exacerbation in health and safety of working conditions. What are you planning to do for the protection of miners and your own reputation?

How will you encourage Sibanye Stillwater to invest into improvements of working and living conditions in Marikana?

How will you supervise that Lonmin and Sibanye Stillwater will comply with the South African mining laws? Will you make the results of your reviews transparent?

Through the audits at Lonmin you aimed to contribute to the improvement of living and working conditions. When do you plan to publish the results of these audits to allow other stakeholders like us to review the implementation of the recommendations?

What was the turnaround between BASF and Lonmin during the last business year? Will you join Daimler and plead for binding compliance with rules and human rights standards in the supply chain?

We appeal to you to take action, not to tolerate the dangerous working conditions, but to make it possible for the people who work for your corporation to mine the central raw material platinum to live a dignified life. Do justice to your claimed role of leadership, and do lead in matters of sustainability and social responsibility of companies.

Many of the shareholders present here rely on you – we do hope, together with the people of Marikana.”

Russia Should Get Behind Arctic Ban on Dirty Fuel

Russia is watering down a block on heavy fuel oil — a toxic pollutant — in the Arctic. That could be a dangerous mistake.

n recent years, Russia has emerged as a global leader in the production and transportation of liquefied natural gas (LNG).

The projects are highly innovative, mighty impressive, and very expensive.

However, Russia’s strides in switching to LNG in the Arctic will be hindered by their reliance on heavy fuel oil (HFO). HFO, known also as bunker fuel or mazut, is a thick, tar-like substance — a dangerous pollutant, packed full of contaminants.

While much of the Russian business community seems to understand that it has no place in Arctic waters, the Russian government has spearheaded diplomatic efforts to water down a proposed international ban on the use of mazut in the Arctic.

That could be a dangerous mistake. The Russian government, scientists, and civil society should take heed of these cues from some of the country’s largest businesses and support the transition away from mazut.

Mazut is kaput

Shipping along the Northern Sea Route — an Arctic passage which cuts naval journey times from Europe to Asia, but is only accessible in warmer summer months — is booming. Since 2017, volumes have gone up by more than 430%, eclipsing records set in the Soviet era.

LNG already makes up most of the transported cargo volumes, but despite investments in gas infrastructure, Russia continues to rely on heavy fuel oil in the Arctic. In November 2019, then-Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev called on the Murmansk Governor Andrey Chibis to find a “systematic solution” to the problem of growing expenses for heavy fuel oil — the issue of mazut had been elevated to the highest-levels of decision-making in the country.

Russia’s business leaders understand that the future of mazut is kaput and are shifting their rubles to LNG.

In a recent interview with business daily Kommersant, Director of Gazprom Neft’s downstream business unit Mikhail Antonov affirmed the company’s intention to “almost completely abandon heavy fuel oil.” The company’s leadership is fully intent on implementing the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) pending ban on the use and carriage for use of heavy fuel oil in the Arctic.

The country’s biggest energy players are investing heavily in cutting-edge LNG technology to support this transition.

Gazprom, for instance — together with Royal Dutch Shell, Mitsui, and Mitsubishi — owns the first of its kind LNG plant, Sakhalin 2, and operates Russia’s only floating storage and regasification unit, the Marshal Vasilevskiy. In August, the government approved Novatek’s concept of a floating LNG thermal power plant in the northeast region of Chukotka.

At the opposite end of the Northern Sea Route, Novatek is building a large-capacity offshore LNG facility near Murmansk, and the company also owns 50% in Yamal LNG, an operational plant with infrastructure and 15 ships which operate year-round. Novatek’s ambitious expansion plans include buying a $12 billion fleet of nearly four dozen icebreakers to service its gas fields in the Yamal and Gydan Peninsulas in northern Siberia.

To ban or not to ban?

The use and carriage of heavy fuel oil has been banned in Antarctic waters since 2011, and now is the time to protect the fragile Arctic region from the hazards of mazut spills.

Draft IMO plans would extend that ban to the Arctic, starting in July 2024, although key exemptions and waivers — spearheaded by Russia — will allow some ships to burn HFO until 2029.

Judging by Gazprom Neft’s rhetoric, Russia’s business leaders are inclined to transition away from HFO even before 2024 — that’s good news for the Arctic.

But unfortunately, the possible waivers and exceptions to the ban will hinder its implementation, allowing 84% of mazut use to remain. According to the U.S.-based International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), the proposals would reduce black carbon — soot — emissions by a mere 5% before the ban comes into full effect in 2029.

While Russian businesses active in the Arctic are making strides to move away from mazut, there are important voices in Russia who are opposed to a ban altogether.

Gennady Semanov of the Central Marine Research and Design Institute, for instance, has argued against the ban, branding it a political tool to delay Russia’s economic development of the Arctic. According to him, black carbon emissions can only affect the melting of snow and ice when ships are located in icy conditions. He also argued that a heavy fuel oil spill would cause much less harm than a comparable spill of diesel oil.

Some indigenous groups in Russia are also against the ban, worried about the impact it could have on livelihoods in the region. Earlier this year the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) submitted a letter of concern to the IMO over the proposed ban. It argued a block on heavy fuel oil “will entail a number of significant negative socio-economic consequences, primarily on the local population and indigenous peoples of the Arctic.” Specifically, it feared the ban would lead to higher prices for delivering goods to the tricky Arctic areas, which would have a debilitating effect on the local population.

Such voices — coming from both the scientific and indigenous communities — are exerting an influence on Russia’s diplomatic negotiations, and stand in contrast to views in other parts of the world, where indigenous leaders and scientists are largely in agreement over the need to implement an effective ban on the use of heavy fuel oil in the Arctic.

Inuit communities in Canada, for instance, live in no less remote locations than their Russian counterparts, yet the Inuit Circumpolar Council is loudly in favor of Canada’s support for a mazut ban. Regarding the socio-economic impact, government subsidies to local communities are an effective tool to reduce harm during the transitionary period following the ban.

The Clean Arctic Alliance, a coalition of nonprofit organizations and scientists, is actively campaigning for the IMO to ensure it implements an effective ban on the use of heavy fuel oil.

Dangerous threat

Any oil spill in the Arctic is a catastrophe — as the people of Norilsk learned this summer after the oil spill at Nornickel facilities.

A heavy fuel oil spill raises the stakes, because it would be impossible to clean up. Mazut emulsifies on the ocean surface. In cold water it sinks to the ocean floor and can travel to warmer areas, rising back up and coating beaches.

Russia’s recent actions to advance its LNG infrastructure in the Arctic demonstrate that the business community is adjusting to the reality of a ban on heavy fuel oil. The international community can use the IMO as a platform for engaging in a dialogue with civil society to address the concerns of different constituencies, such as indigienous peoples, as well as the scientific dilemmas posed by the likes of Semanov.

Because ultimately, Russia’s ongoing reliance on HFO in the Arctic will delay — not advance — its economic development of the region, which is being spearheaded by audacious LNG prospects, and an upcoming LNG fleet for the Northern Sea Route. More importantly, the continued use of heavy fuel oil in the Arctic would mean the continued and dangerous threat to the environment and coastal communities of the region.

THE ARCTIC’S FUTURE IS SHAPED BY INDIGENOUS YOUTH LEADERS

Building relationships among peoples across the Arctic borders was a vision the Arctic Indigenous youth had when they came together in the very first Arctic Youth Leaders’ Summit held in Finland last November of the previous year. Bearing witness to the common issues their respective countries were experiencing in the Arctic regions, their idealism and enthusiasm to articulate these and share common ways forward were proof that the future in these northernmost ends of the globe will be in good hands when the time comes.

The Summit is a promising start of the Arctic Indigenous youth’s assertion of their responsibility and stewardship of the land and its resources in the face of rapid socio-economic and environmental changes that are largely attributed to modernization, assimilation into mainstream culture and influence of religions.

The summit participants who represented various indigenous youth organizations from the Arctic regions that include Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Finland, Russia, Sweden and Norway shared experiences and views, fears and hopes for their communities. Discussions dwelt on the health and wellbeing of their communities that are closely tied to strengthening of indigenous self-determination; protection of cultural identity; reducing the peoples’ exposure to violence; dealing with their experiences of discrimination and historical trauma; and the rapid changes in their environments due to anthropogenic climate change.

They articulated their need for guidance from accurate and accessible indigenous knowledge and history bearers who will teach them beyond western educational institutions for them to better learn of their identity and life ways. Traditional knowledge and their languages are inextricably linked and these thrive in their physical environment which is presently threatened and endangered. Their indigenous languages teach them about indigenous biodiversity, climate change adaptation, and resilience to cope with the realities of the changing Arctic.

Looking forward as they are given the mantle of leadership, the youth are well aware of the urgency to address the proper management of their resources as crucial in promoting the physical wellbeing of their communities in terms of food security as they protect their traditional activities of herding and fishing. They see the need to improve housing, education, healthcare and social-service delivery infrastructure. All these shall contribute to the people’s mental wellbeing.

The realization that they shared similar issues, learnings, and challenges propelled them to draw up a Declaration, which is their statement about their concerns, dreams and their proposals for their future. This also bound them more closely to explore the establishment of linkages and organizational form of solidarity and support to one another and speedier communication in the Arctic region. They stressed the urgency to deepen and strengthen their ties which led them to the formation of a circumpolar network for the youth. Thus the “Arctic Indigenous Youth Council” was formed for future collaboration and as a concrete expression of unity among the Arctic indigenous youth.

The meeting of generations of Arctic Indigenous leaders was realized soon after the Arctic Youth Leaders’ Summit. In recognition and acknowledgement of their invaluable role in leadership in community concerns the youth were subsequently given the opportunity to give their opening remarks during the first session of the 6th Arctic Leaders’ Summit (ALS6). The latter is composed of Permanent Participants in the Arctic Council representing six Indigenous Peoples’ organisations. The Permanent Participants of the Arctic Council had decided early on to establish Youth Focal Points who will share the youth’s thoughts, ideas and viewpoint about their present and future concerns to the Arctic Council. Most of the elected Focal Points are the Youth Summit participants. The youths’ participation to the elders’ event was made possible and ensured by the Permanent Participants. The youth were welcomed and their presence appreciated by being given the space to truly participate in the program.

The results from the Youth Summit workshops were framed in a Declaration that the youth representatives prepared and presented in the ALS6 panel discussion with the theme “A Look at the Arctic Leaders’ Summit History: Does it Provide Guidance for the Future?” In response, the Youth Declaration highlighted the youth’s myriad concerns on the environment, economic development and infrastructure projects, food sovereignty, indigenous knowledge, culture, languages, education, mental health, communication and about violence against Indigenous Peoples. This occasion provided for an adequate and meaningful intergenerational dialogue, to learn and to share thoughts and information among the elders, youth, and other leaders.

The Youth Declaration was printed and shared with the 6th Arctic Leaders’ Summit participants. It was published as an attachment to the ALS6 declaration, proof that the Arctic leaders value and respect the views and thoughts of their youth. This Declaration has been widely disseminated among organizations, communities, and in social media.

The Indigenous youth expressed how much the Youth Summit was timely and necessary and how truly empowered they felt after the encounter and exchange. The importance of future collaboration has been spelled out through planning meetings. Already, they look forward to an annual circumpolar meeting and work has already started, with several follow-up online meetings after the event. They confidently stated that it was important for the youth to meet again and to have closer collaboration since they are not only future leaders, but present leaders.

Below please find the links to the proceedings and coverage of the Summits:

Arctic Council interviews

Arctic Council made interviews of the ALS 6 participants and two of the youth participants, Seqininnguaq Poulsen and Elizabeth Ferguson took part to that.

Link to the videos:

https://vimeo.com/showcase/6580185

(The project Arctic Indigenous Youth Leaders’ Summit was implemented by the Arctic Council Indigenous Peoples Secretariat (IPS) in Finland in December 2019 with the support of PAWANKA Funds.)