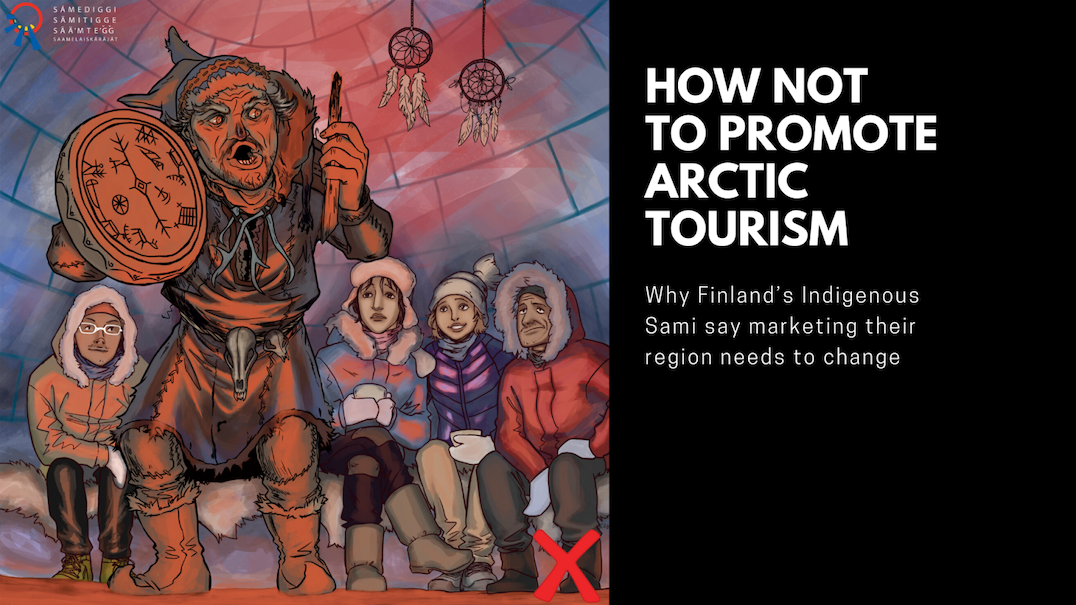

Eye on the Arctic report How not to promote Arctic tourism among finalists at Canadian Online Publishing Awards

Eye on the Arctic has been named as a finalist at the 2020 Canadian Online Publishing Awards (COPA) in the Best Investigative Article or Series category, Media section, for its report How not to promote Arctic tourism, the awards organizers announced on their website.

In How not to promote Arctic tourism: Why Finland’s Indigenous Sami say marketing their region needs to change, Eye on the Arctic journalist Eilís Quinn explores how destructive Indigenous stereotypes became embedded in Finland’s tourism industry and how the Sami are now working to undo them.

Eye on the Arctic joins four other nominees in the same category : Ha-Shilth-Sa; HuffPost Canada; PressProgress; and Victoria News.

The 2020 COPA winners will be announced online in January on a date yet to be determined. Because of COVID-19, they’ll be no in-person event this year.

Entries are reviewed by a panel of experts from various fields with prizes divided between five sections: academic, business, consumer, media, ethnic.

Established in 2009, the COPAs “bring together all the media brands and companies that are producing content online,” according to their website.

Masthead Magazines, which produces the awards, is based in Ontario, southern Canada. Masthead “is not affiliated with any trade organization or publishing lobby groups,” COPA’s website says.

Eye on the Arctic was previously awarded the silver medal at the 2019 COPA awards in the Best Investigative Article or Series category for Death in the Arctic: A community grieves, a father fights for change, also by Eilís Quinn.

Morgan Freeman Asks Navajo About The Meaning Of Life And The Creator

Freeman, host of a six-part documentary series airing on the National Geographic Channel, visited the Navajo Nation to ask poignant questions about God.

His series, “The Story of God,” explores religions around the globe in a journey that seeks to “shed light on the questions that have puzzled, terrified and inspired mankind,” Nat Geo said in a statement. In his series, Freeman attempts to uncover the meaning of life, the origin of deities and similarities among the different faiths.

“Over the past few months, I’ve traveled to nearly 20 cities in seven different countries on a personal journey to find answers to the big mysteries of faith,” Freeman said in a statement. The series premiered April 3, and new episodes air every Sunday. Maysun was featured for about eight minutes during the April 17 episode, titled “Who is God?”

The 50-minute segment also included footage from Egypt and Israel, where Freeman explores monotheism, and to India, where Hindus worship millions of gods. And on the Navajo Nation, he observes the Kinaaldá, during which girls communicate with Changing Woman, one of the Navajo Holy People.

The Kinaaldá is a sacred ceremony that includes several rituals designed to ensure a girl grows into a strong and kind woman. Over the course of four days, the girl bathes, ties her hair back, runs toward the east and bakes a corn cake in an earthen pit. A medicine man performs songs that invite Changing Woman to help the girl enter womanhood. When the ceremony is complete, the girl is introduced to the deities as a woman and invited to take her place in the world.

“I think what Morgan Freeman was looking for was the way we as Navajos experience God’s different types of conversation,” said Michele Peterson, Maysun’s mother. “The songs we sing are saying the girl is coming out as a woman. Because of those songs, we are surrounded by our deities.”

Only small portions of the actual ceremony can be filmed, said Tom Chatto, a Navajo medicine man who performed Maysun’s Kinaaldá. Chatto also acted as a consultant for the film crew, determining which details of the ceremony could be shared on television.

In fact, most of the ceremony that aired on National Geographic was a reenactment, Chatto said.

“The real one, you can film parts of it,” he said. “But for the TV show, we just reenacted it. We just showed the parts that are OK for the world to see.” Even in the reenactment, there were places Freeman wasn’t allowed. Near the end of the ceremony, Peterson pulls a blanket over the door of her hogan. Freeman is left outside.

“The most important thing was to do what was appropriate,” Peterson said. “We made sure we were very respectful, and that meant closing the hogan with a blanket or telling the cameras they had to stop filming.” Freeman did witness some of the songs, the morning runs and the ceremonial cutting of the corn cake. In the segment, Freeman takes a big chunk of the cake and holds it up to his mouth.

Through the lens of an Inuk woman

Melting ice threatens Inuit way of life. To heal our world, Canada will need imagination and an Indigenous-aligned economy

As an Inuk woman, my life’s journey and work has been driven by my traditional upbringing, which taught me early on that the land is an extension of ourselves. The Inuit way of life is dependent on the cold, ice and snow. For us, ice is transportation and mobility; it allows us to hunt for the nutritious traditional food that sustains us. As the planet warms, the vanishing ice becomes an issue of safety and security, first and foremost. The ice forms later in the fall and breaks up earlier in the spring. Unpredictable weather makes it difficult to use Indigenous knowledge to read the changing conditions. As a result of melting permafrost and coastal erosion, some homes are buckling and need to be moved, and some homes, in Alaska in particular, are falling into the sea.

I see the parallels between the safeguarding of the Arctic and the survival of Inuit culture in the face of past, present and future environmental degradation. Attempting to awaken the world to this common understanding has guided my work. I have spent the last 15 years speaking to many audiences, offering a human story from the unique vantage point from which I come, my Inuit culture serving as the very anchor of my spirit. Travelling from city to city, province to province, across our large country of Canada, I was busier than I have ever been, as Canadians finally started to understand the Arctic connection – until COVID-19 hit. Now, many months later, I have learned to carry on with these “teaching” moments via Zoom and recorded messages.

When you share the human side of climate change, people relate to it better. The issues become clearer for them, no matter where they come from, when they can see themselves in human stories. In other words, if we can shift climate change out of the language of science, politics and economics and bring it home to the issues of health, food security, culture, families, communities and human rights – not just for Inuit, but for us all – it is more relatable. It helps to mobilize people to take action to address climate change in a tangible way.

After my book The Right to Be Cold came out, I was invited to New Zealand and Australia for book festivals. I was on a panel with Tim Flannery, a well-known Australian climatologist and author. At the end of the panel discussion, an audience member asked Tim a question: “What is lacking in our world, when we now know the science so clearly, that is not allowing us to take urgent action on climate change?” Tim’s answer struck a chord with me: “Imagination.”

Imagine we can do things differently. Imagine we can address climate change differently. Imagine we can innovate sustainable economies differently.

I believe we need to not only imagine a new way of doing things, but we must, as Canadians, re-imagine our unsustainable economic values and realign them with Indigenous values. Inuit and other Indigenous Peoples are not just victims of globalization wreaking havoc on our communities. With our understanding of nature, which we depend on as our food source and as a powerful character-builder for our children, Indigenous Peoples have much to offer in helping to galvanize a largely disconnected urban world. The pandemic has shown us just how interconnected we all are. The knowledge, values and wisdom of Indigenous Peoples hold the answers to the many challenges our world faces today. I strongly believe Indigenous wisdom is the medicine we seek in healing our planet and creating a sustainable world.

Transformation must happen from a very personal place; our attitudes, outdated policies based on colonialism, and unsustainable businesses must be shed and changed to meet a new world order, one that embraces the real meaning of our common humanity.

As author and spiritual leader Marianne Williamson says, “Personal transformation can and does have global effects. As we go, so goes the world, for the world is us. The revolution that will save the world is ultimately a personal one.”

New Zealand Appoints First Indigenous Female Foreign Minister

New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced parliament’s newest ministers Monday, including the appointment of Nanaia Mahuta to the role of Minister of Foreign Affairs; the nation’s first Indigenous woman to hold the position.

Just shy of a quarter-century of political prowess, including her most recent roles as Minister for Māori Development and Local Government, Mahuta will join what is becoming one of the most diverse parliaments in the world. “I am excited by this team,” Ardern said. “They bring experience from the ground, and from within politics. But they also represent renewal and reflect the New Zealand we live in today.”

Mahuta is one of New Zealand’s 5 Māori ministers. Also contributing to the cabinet’s cultural diversity are members of parliament Ibrahim Omer and Vanushi Walters, parliament’s first leaders of African and Sri Lankan origin.

The country of 4.8 million people is represented by 120 elected members of parliament. At the moment, more than half of those representatives are women and about 10% are openly lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender.

New Zealand’s government is also shifting gears by bringing in younger members of parliament. Ardern, who began her second term in October, became the world’s youngest female head of government when elected as New Zealand’s 40th prime minister in 2017; she was 37 years old at the time.

Professor Paul Spoonley, Pro Vice-Chancellor of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Massey University, believes New Zealand’s parliament is the most diverse in the nation’s history in terms of gender, ethnic and indigenous representation. “What we have seen is a departure of many of the older, male, white MPs including some who have been in parliament for over 30 years,” Spoonley told Reuters in an October interview.

FINDING THE NEXUS BETWEEN WATER, ENERGY AND FOOD IN THE ARCTIC

The Sustainable Development Working Group of the Arctic Council will launch the first water, energy and food nexus study in the Arctic. The project will identify interconnections between water, energy and food systems in ways that will contribute to the attainment of the UN Sustainable Development Goals in the Arctic

In 2015, the United Nations introduced the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. At the core of the Agenda are 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that serve as benchmarks for achieving equality, prosperity and environmental sustainability around the world.

While Agenda 2030 is a global platform, the Sustainable Development Working Group of the Arctic Council (SDWG) recognizes that its activities naturally contribute towards achieving SDG targets and advancing the sustainable development agenda in the Arctic. However, before those linkages can be further explored, the SDWG stresses the need to better understand the nexus – or the connections and interactions – that occur between SDG targets.

“Simply ticking off SDG targets and failing to consider the nexus between them could result in ill-informed and unintended policy outcomes,” cautioned Stefán Skjaldarson, Chair of SDWG. “For example, advancing one target may inadvertently have a negative impact on the ability to reach other targets. These oversights are particularly problematic in some regions of the Arctic where Indigenous peoples experience greater challenges relative to their national averages. That is why it is so important to first focus on nexus research to ensure that SDG targets can be sustainably achieved in the Arctic.”

WEF-Livelihood Nexus (John Natcher)

In October 2020, the SDWG launched its newly approved project to study the relationship between water, energy and food (WEF) – three pervasive systems that intricately interact in the circumpolar North. This project is led by Canada, Finland and Iceland. It will examine three SDGs: SDG 2 – ending hunger and achieving food security for all; SDG 6 – ensuring the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all; and SDG 7 – ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all. This is the first WEF nexus study conducted in the Arctic. This analysis will inform research planning and effective policies for sustainable development in the region.

SYNERGIES VERSUS TRADE-OFFS

To study the nexus between water, energy and food, the SDWG will look at synergies and trade-offs between these systems. Synergies include the positive effects of achieving multiple SDG targets through simultaneous interventions, for example through mutually beneficial infrastructure. Trade-offs occur when advancements towards one target have a negative impact on the ability to reach others, whether due to environmental degradation or intensive use of resources.

In addition to calculating the positive and negative interactions between WEF systems, the SDWG will also evaluate the potential impacts on cultural ecosystem services, environmentally based livelihoods and the territorial rights and interests of Indigenous peoples. For example, wind energy may have a positive effect on SDG 7 (sustainable energy) but a negative impact on the livelihoods of herding peoples.

A NEW APPROACH TO WEF NEXUS STUDIES

In the past, WEF nexus studies have been criticized for prioritizing the maximization of resources use and extraction over the livelihoods of resource dependent communities. The SDWG’s project will advance a novel approach to WEF nexus research that explicitly includes the livelihoods of Arctic residents into a system where social-ecological interactions are prevalent and sustainable solutions are found.

The oversights in past WEF nexus studies fail to acknowledge inequalities felt at the community level. Indigenous peoples in the Arctic are heavily reliant on WEF systems to meet their livelihood needs, yet disproportionately experience insecurities in those systems. These inequalities have been made more apparent during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“By improving our understanding of WEF interactions and how they relate to Indigenous livelihoods, we may be in a better position to increase resiliency within the water, energy and food systems and respond more effectively to future shocks like Covid-19,” said David Natcher, professor at the University of Saskatchewan and project lead for the SDWG’s WEF nexus study.

PROJECT OUTCOMES

Ultimately, the project will produce new insights and address knowledge and data gaps to support the SDWG’s efforts to meet the SDG targets in the Arctic. With the participation of the Arctic Council Indigenous Permanent Participants, this research represents a unique opportunity to respond to the United Nations’ call to locate the rights and interests of Indigenous peoples to the center of the SDG agenda.

“By examining the synergies between WEF systems and their influence on the livelihoods of Arctic peoples, we will create innovative pathways for the co-production of knowledge, novel technologies and predictive capabilities informed by both western and Indigenous Knowledge systems,” said David Natcher.

Information collected through this research will be added to an online Decision Support Tool that will combine WEF and livelihood data in ways that can be easily interpreted by decision-makers. A new online WEF nexus course will also be developed through the University of the Arctic. The course will facilitate community responses to WEF related challenges and will be tailored to undergraduate students, government and industry professionals who work in WEF related areas. The project will culminate in an international conference – Nexus Thinking in the Arctic, with keynote presentations made by international experts from in and outside the Arctic.

“This research project is ambitious,” said Stefán Skjaldarson. “However, the current opportunities and challenges experienced in WEF systems in the Arctic – and the implications for Arctic peoples – demand our ambitious efforts.”

7 Native American Inventions That Revolutionized Medicine And Public Health

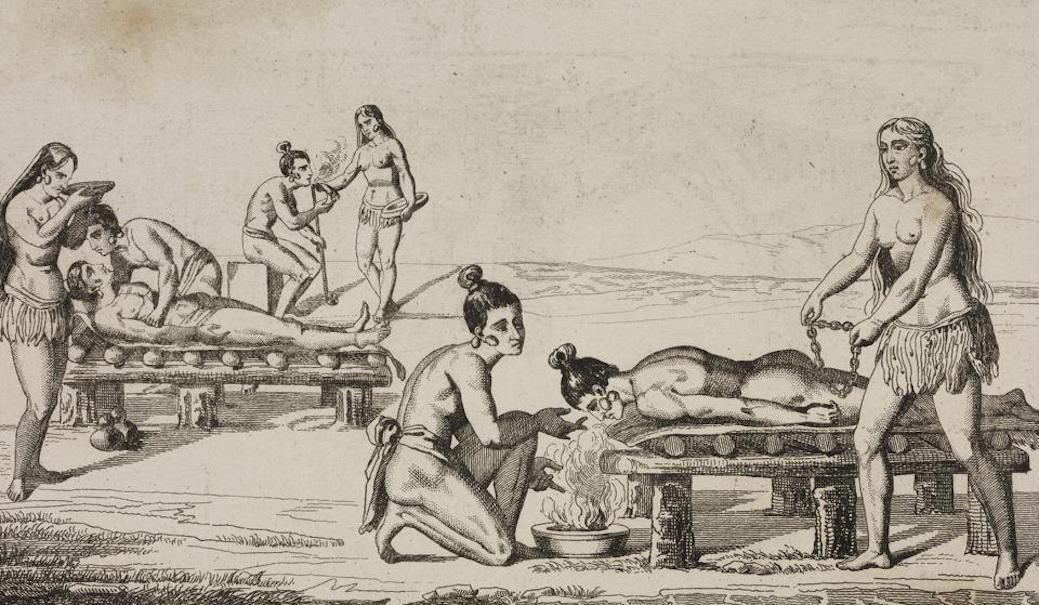

November is National American Indian Heritage Month, a time of recognition for the substantial contributions the first Americans made to the establishment and growth of the U.S. But, the month and remembrance, like many Native influences, still frequently go unrecognized in our day-to-day lives. Whether it’s the invention of vital infrastructure such as cable suspension bridges or sport for fun like lacrosse, so much of what exists in modern culture today is a direct result of what was created before newcomers occupied these lands.

And the world’s health ecosystem, ranging from preventative measures to administration of medicine is no different, owing much of its practices and innovations to those ancestral peoples and healers.

Here are seven inventions used every day in medicine and public health that we owe to Native Americans. And in most cases, couldn’t live without today:

1. Syringes

In 1853 a Scottish doctor named Alexander Wood was credited for the creation of the first hypodermic syringe, but a much earlier tool existed. Before colonization, Indigenous peoples had created a method using a sharpened hollowed-out bird bone connected to an animal bladder that could hold and inject fluids into the body. These earliest syringes were used to do everything from inject medicine to irrigate wounds. There are also cases in which these tools were even used to clean ears and serve as enemas.

2. Pain Relievers

Native American healers led the way in pain relief. For example, willow bark (the bark of a tree) is widely known to have been ingested as an anti-inflammatory and pain reliever. In fact, it contains a chemical called salicin, which is a confirmed anti-inflammatory that when consumed generates salicylic acid – the active ingredient in modern-day aspirin tablets. In addition to many ingestible pain relievers, topical ointments were also frequently used for wounds, cuts and bruises. Two well-documented pain relievers include capsaicin (a chemical still referenced today that is derived from peppers) and jimson weed as a topical analgesic.

3. Oral Birth Control

Oral birth control was introduced to the United States in the 1960’s as a means of preventing pregnancy. But something with a similar purpose existed in indigenous cultures long before. Plant-based practices such as ingesting herbs dogbane and stoneseed were used for at least two centuries earlier than western pharmaceuticals to prevent unwanted pregnancy. And while they are not as effective as current oral contraception, there are studies suggesting stoneseed in particular has contraceptive properties.

4. Sun Screen

North American Indians have medicinal purposes for more than 2,500 plant species – and that is just what’s currently known between existing practices. But, for hundreds of years many Native cultures had a common skin application that involved mixing ground plants with water to create products that protected skin from the sun. Sunflower oil, wallflower and sap from aloe plants have all been recorded for their use in protecting the skin from the sun. There are also noted instances of using animal fat and oils from fish as sunscreen.

5. Baby Bottles

It wouldn’t be considered sanitary – or safe – by today’s standards, but long before settlers made their way to American lands, the Iroquois, Seneca and others created bottles to aid in feeding infants. The invention consisted of the insides of a bear and a bird’s quill. After cleaning, drying and oiling bear intestines, a hollowed quill would be attached as a teat, allowing concoctions of pounded nuts, meat and water to be suckled by infants for nutrition.

6. Mouth Wash & Oral Hygiene

Although tribes across the continent used various plants and methods for cleaning teeth, it is rumored that people on the American continent had more effective dental practices than the Europeans who arrived. In particular areas, mouthwash was known to be made from a plant called goldthread to clean out the mouth. It was also used by many Native cultures as pain relief for teething infants or a tooth infection by rubbing it directly onto the gums.

7. Suppositories

Hemorrhoids are nothing new. Nor is the pain and discomfort associated with having hemorrhoids. But before modern-day solutions and dietary changes, Indigenous peoples throughout the Americas created suppositories from dogwood trees. Dogwood is still used today (although not often) externally for wounds. But hundreds of years ago small plugs were fashioned by moistening, compressing and inserting the dogwood to treat hemorrhoids.

It’s easy to go about our day-to-day lives without thinking about the role that public health and medicine play in keeping us safe and healthy. But it’s even easier to take those things for granted without recognizing the brilliant innovations and inventors that got us where we are today. In some instances, we have sanitized, improved upon and perfected our modern-day practices. But in other instances, we are not much further than our ancestors were. Those healers who knew how to use the land and its resources to produce effective methods and substances for ailments.

As technology moves us ever forward, let’s not forget that as we grow into the future, we are still rooted in history.

After 250 years, Native American tribe regains ownership of Big Sur ancestral lands

A northern California Indian tribe’s sacred land is now back under their ownership, thanks to the help of a conservancy group.The Esselen Tribe, one of the state’s smallest and least well known tribes, inhabited the Santa Lucia Mountains and the Big Sur coast for thousands of years, according to their website. Nearly 250 years ago, their land was taken from then by Spanish explorers, according to the tribe’s history. The tribe remained landless until Monday.

The Esselen Tribe of Monterey County (ETMC) closed escrow on a $4.5 million deal with Western Rivers Conservancy (WRC), an environmental group, to purchase nearly 1,200 acres in Big Sur. The WRC acquires land with the purpose of finding a long-term steward that will conserve the natural habitat. In October the group announced it helped the tribe to be rewarded a grant through the California Natural Resources Agency that covered the purchase of the land.”It is with great honor that our tribe has been called by our Ancestors to become stewards of these sacred indigenous lands once again,” Tom Little Bear Nason, Tribal Chairman of the ETMC, said in a statement in October.”These lands are home to many ancient villages of our people, and directly across the Little Sur River sits Pico Blanco or ‘Pitchi’, which is the most sacred spot on the coast for the Esselen People and the center of our origin story.”

Future of the land

The land, which was known as the Adler Ranch, first came to the attention of WRC in 2015 when the long time owners had being trying to sell the property for years, Sue Doroff, president of WRC, told CNN on Wednesday.

Doug Steakley/Western Rivers Conservancy

The area piqued the conservation group’s interest because it is known for its giant redwoods, an ideal nesting place for one of the largest flying birds in the world, the California condor.”The old-growth redwoods on this property are genetically adaptive to the warmer dry climate of Big Sur,” Doroff said. “These trees will be important for the future effort to assist in redwood survival.”The Little Sur River runs along one side of the property with a tributary jutting onto the land, which is a spawning ground for the South-Central California Coast Steelhead, said the WRC. Both these species are in dire need of conservation. The condor is listed as endangered and the steelhead as threaten on the Endangered Species Act.Both parties agreed that the land will not be commercially developed on and that conservation efforts will continue, according to Doroff.”We are proud of our involvement here and conserving this landscape,” Doroff said. “We are honored to be a part of rebuilding the Esselen Tribe.”In addition to conservation efforts, the ETMC plans on building a village that other indigenous tribes in the area can utilize. They are also planning to host public educational events to teach others about their culture, according to Doroff.”We are going to conserve it and pass it on to our children and grandchildren and beyond,” Nason told The Mercury News. “Getting this land back gives privacy to do our ceremonies. It gives us space and the ability to continue our culture without further interruption.”

Russia: Amendments to ‘Foreign Agents’ Law – A Death Sentence for Civil Society

Civil Rights Defenders expresses grave concern over proposed package of draft laws to Russian legislation regulating association. The amendments could mean a death sentence for unregistered initiatives and independent non-governmental organisations.

In November 2020, the Russian government proposed amendments to broaden its notorious 2012 ‘foreign agents’ legislation, which concerns domestic organisations and branches of foreign NGOs operating in Russia. The amendments will 1) increase the burden on organisations as well as the government’s control over their operations; 2) increase the risk for individual activists; and 3) contravene Russia’s constitution and its international obligations to ensure freedom of association.

More Bureaucratic Burdens for NGOs

One of the new amendments dictate that NGOs labelled as ‘foreign agents’ will be required to provide the Ministry of Justice with information on their programmes and the implementation thereof, including their activities, public events, and finances, in advance and on an annual basis. The Ministry of Justice will in turn decide whether an organisation can implement its planned programmes. If the Ministry prohibits implementation, the NGO must comply, or be forced to close by court order.

In addition, unregistered associations or initiative groups can be labelled ‘foreign agents’ and would then be required to report activities and finances for government approval. Therefore, Russian authorities will have even more control to prevent groups, such as the independent monitoring association GOLOS, from implementing their activities, including observation missions of the parliamentary elections slated for 2021.

According to Russian civil society representatives, the language in the amendment is not specific as to how the Ministry will make such determinations over NGO activities. For example, an organisation working on political prisoners’ support might be forced to stop this activity because the state asserts that there are no political prisoners in the country.

Human Rights Defenders at Greater Personal Risk

The amendments will increase the personal risks on Russian human rights defenders and civil society activists by establishing an ‘individuals serving as foreign agents list.’ The list will contain personal data – the scope of which is unclear in the law – and be publicly available. The bill proposes that individuals, regardless of their citizenship, can be recognised as ‘foreign agents’ if they engage in political activities and receive money, an asset, or ‘organisational and methodological help’ from foreign sources.

As such, individuals will be required to report their ‘political activity’ and how they spend their foreign funds to the Ministry of Justice every six months. In the case of a ‘foreign agent’ organisation whose employees retain a salary from foreign funds, the employees must report their financials. Such demands constitute a violation of the right to privacy.

Additionally, the amendments expand the already controversial concept of ‘foreign source’, which has been used to recognise an entity or individual as a ‘foreign agent’. The amendments include not only foreign governments, citizens, or organisations but also Russian citizens and organisations that have an affiliation with a foreign citizen or stateless person. The only safeguard to avoid the label and consequences of ‘foreign agent’ in the country will be to accept state funds exclusively.

Independent Expert: Amendments Are Unconstitutional

According to Maxim Krupsky, an independent legal expert, who analysed the legislation, the proposed bills are unconstitutional and violate the principle of legal certainty i.e. demands of the law must be clear enough for adherence and implementation, as understood by the Russian Constitutional Court and the European Court of Human Rights.

The terms used in the bills are vague and have no legal determination, meaning the provisions could be applied arbitrarily, unjustly, and unreasonably. And organisations required to meet the demands of the new legal provisions will have no legal remedy to dispute a decision by the Ministry of Justice.

According to the legal expertise of the draft bill, the proposed legislation is ‘excessively repressive and provides unreasonably broad discretion to enforcement institutions <…> which may lead to the gross violations of (association and individual) rights as well as the balance of public and private interests’ (Krupsky, M. The independent anti-corruption expertise on the Bill ‘On taking additional measures to counter threats to national security,’ p. 30.)

Given the threat to civil and political liberties, Civil Rights Defenders calls on the State Duma of the Russian Federation to retract these amendments to the ’foreign agent’ legislation. These further restrictions under Russia’s foreign agent law are detrimental to freedom of association and to civil society, which is a key component of a functioning democracy. Guarantees of such freedoms are the core part of Russia’s international commitments on human rights.

Commissioner for Human Rights calls on the State Duma to refrain from adopting legislation which violates the rights of NGOs and civil society activists

“I have been following closely recent discussions concerning a number of new bills related to NGOs and, in particular, I note that Russian civil society has expressed criticism of these bills. Based on all the information received, I call on the State Duma of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation to reject a number of pending bills that would make the already very restrictive legislation on NGOs even more limiting, undermining civil society and restricting freedoms of association, assembly and expression. I recommend that the lawmakers conduct a thorough review of the current legislation on NGOs in consultation with all relevant international and national human rights stakeholders, including Russian civil society and national human rights structures, to align it with European and international human rights standards”, said the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Dunja Mijatović, in a statement today.

“Bill no. 1052523-7, as tabled by the Government, would allow the Ministry of Justice to interfere with the statutory activities of both NGOs that receive foreign funding and international or foreign NGOs (INGOs) operating in Russia. In particular, the bill provides that the NGOs concerned would have to communicate information in advance and report about their planned projects and events to the Ministry of Justice, while the latter would have discretionary power to approve or ban those activities. The bill does not provide any guidance as to what actions could be prohibited and on what grounds. Failure to comply with such a ban would lead to the liquidation of the NGO concerned.

European human rights standards on the legal status of NGOs provide that they should be free to pursue their objectives through a wide range of activities, including research, education and advocacy, and in doing so, they should not be subject to direction by public authorities. According to the well-established case-law of the European Court of Human Rights, granting the executive legal discretion expressed in terms of unfettered power in matters affecting fundamental rights would be contrary to the rule of law which is one of the basic principles of a democratic society. Furthermore, the dissolution of an NGO can only be applied for serious misconduct and as a last resort, when all less restrictive options have been unsuccessful. When it comes to the imposition of sanctions, it appears that the draft law in question fails to meet the requirements of proportionality and necessity, as the dissolution of the NGO concerned is proposed as the only and immediate sanction to be initiated by the Ministry of Justice.

Another worrying legislative proposal that has been made is to extend the scope of the activities that NGOs receiving foreign funding are currently prohibited from engaging in. In addition to the existing ban on taking part in public monitoring commissions, public consultations on draft laws, or observation of elections, Bill no. 1057230-7, would prohibit such NGOs from providing financial or material support for public events. Such a blanket and discriminatory ban would significantly affect the freedom of assembly and expression of the civil society groups concerned in contradiction with the guarantees provided by the Russian Constitution and the European Convention on Human Rights. Furthermore, Bill no. 1057914-7 provides that NGOs receiving foreign funding would be excluded from the public consultations that various ministries hold with civil society on a regular basis. The bill does not provide any reasons for stripping these NGOs of their legitimate right to effective participation without discrimination in public decision making. It is also crucial to reiterate the well-recognised right of any NGO to solicit and receive funding not only from public bodies in their own state but also from institutional or individual donors, another state or multilateral agencies. If adopted, such new provisions would only add to the discriminatory treatment of such NGOs under current legislation.

Lastly, I am dismayed by the persistent and increasing spread in recent years in Russia of stigmatisation and harassment of civil society and human rights defenders. This time, Bill no. 1057914-7 provides for this stigmatising label to be applied to unregistered associations and even individuals who receive foreign funding or support and are engaged in activities, which are the most basic and natural forms of the work of civil society. The same bill also extends the requirement to affix stigmatising labelling on any publication or materials disseminated in the mass media or addressed to the state authorities (or the public at large) to include not only such groups themselves but also individuals who are affiliated to them, including staff members. Another problematic proposal that has been made is to deprive the individuals concerned of access to public state and municipal service functions.

As various institutions have already established, the use of stigmatising labels leads to discrimination against the persons concerned and intensifies the chilling effect on their legitimate activities and freedom of speech. The Venice Commission has also criticised the use of such labelling because it means that other people, particularly representatives of state institutions, are very likely to be reluctant to co-operate with those to whom it is applied. All such provisions would contribute to a discriminatory restriction on the legitimate right of the persons concerned to participate in public life and decision making.

All the recently proposed legislative amendments referred to above fall short of the applicable human rights standards on freedom of expression, assembly and association enshrined in the European Convention and might serve as a tool for the further silencing of any form of legitimate criticism of the state authorities from civil society. There is an urgent need for the Russian authorities to change course and to start upholding their human rights obligations by supporting civil society and creating an enabling environment for their legitimate activities.”

Rivers for Recovery: Protecting Rivers and Rights Essential for a Just and Green Recovery

On the 20th Anniversary of the landmark World Commission on Dams Report, a new report from International Rivers and Rivers without Boundaries charts an alternative course for post-pandemic energy development than the revitalization of a failing hydropower industry. As Rivers for Recoverydetails, despite the rhetoric of the hydropower industry, the industry’s global flagship projects continue to prove poor investments. This in addition to destroying critical ecosystems and biodiversity, while devastating local populations, human rights, and food security.

For years, the installation of new hydropower facilities has steadily declined as renewables have rapidly increased. This is a result of a confluence of factors including the growing cost-efficacy of alternatives (especially solar and wind), the lengthy timelines and burdensome costs (social, environmental, and economic) of large dams, a worsening climate crisis, technological innovations in energy efficiency, storage, and transmission, and a growing global movement to keep or return rivers to their natural state. Indeed Cambodia recently announced a 10-year moratorium on Mekong mainstream dams and U.S. governors announced the world’s largest dam removal project will proceed.

Yet, the International Hydropower Association (IHA), far from shifting course, is urging its members to “have shovel-ready projects in place for the post-Covid 19 economic stimulus plans.” In other words, the hydropower industry is seeing the pandemic as an opportunity to profit from recovery funds that would be much better spent elsewhere, including upgrading and improving the efficiency of existing dams.

AREAS IN FOCUS

“The hydro industry is in the business of self-preservation. But humanity’s self-preservation needs to prevail,” said Darryl Knudsen, executive director of International Rivers. “Given the track record and problems inherent in large-scale hydropower, we should be rushing toward alternatives, not channeling money into false solutions.” The report’s survey of major projects that came online immediately prior to the pandemic includes:

The Belo Monte Dam in the Brazilian Amazon.

The project had a pricetag of $10 billion, was fraught with corruption scandals, devastated Indigenous territories and way of life, displaced thousands of families, and harmed critical biodiversity in the globally sensitive Amazon rainforest. What’s more, the project will only deliver a fraction of the 11 gigawatt (GW) capacity it promised. Yet the IHA heralds it as a major success.

The Wunonglong and Dahuqiao Dams in China.

These recent additions to the series of dams on the Lancang, or Upper Mekong River, in addition to the new Xayaburi and Don Sahong Dams in Laos, have contributed to an unfolding ecological disaster downstream in the Lower Mekong Basin that threatens the world’s largest freshwater fishery and the collapse of the region’s “food bowl.”

The Genale Dawa III Dam in Ethiopia.

Finally commissioned after nine years of construction, the dam will restrict flows in such a way that Somalia’s agricultural production and food security could be seriously impaired.

“We have the opportunity for a reset in how we relate to and manage natural resources while developing energy solutions that genuinely address the climate crisis and build economies. It’s critically important we take the opportunity, lest we sink deeper into climate crisis and further accelerate the mass extinction of species.”

– Eugene Simonov, coordinator of Rivers without Boundaries

THE REPORT

in Kratie province, Cambodiab. | Photo by Savann Oeurm, Oxfam

Rivers for Recovery provides an indicative list of destructive projects that are yet in the pipeline but could be stopped with forward-thinking on cheaper, cleaner options by governments; a chance to avoid crippling new debt in the post-pandemic recession. It also provides a detailed roadmap that not only calls for a moratorium on new dams in the economic recovery, but investments in alternatives and increasing efficiency of current dams, and commitments to protect critical biodiversity and the world’s remaining, free-flowing rivers.

What’s more, the report’s findings affirm much of what the World Commission on Dams laid out twenty years ago. The Commission, a multi-stakeholder group from civil society, the private sector, academia, and beyond, examined the environmental, social, and economic impacts of large dams around the globe. And their final report, Dams and Development: A New Framework for Decision–Making, released in November 2000 under the patronage of Nelson Mandela, provided a comprehensive framework for alleviating the competing pressures on our scarce freshwater resources. Globally, rivers and the communities that depend on them remain threatened. And the fight against destructive, expensive, unprofitable dams continues. The Commission’s recommendations remain an important foundation for further innovations as we seek to rebuild economies from the pandemic.