‘It’s cultural genocide’: inside the fight to stop a pipeline on tribal lands

Dressed in a ribbon skirt and mask, Tara Houska gazed down at the trickling waters of the Mississippi near its headwaters. The great American river that eventually flows into the Gulf of Mexico is just a stream in these parts of northern Minnesota.

A pipeline will soon burrow underneath this part of the Mississippi and its surrounding wetlands. It is one of hundreds of water crossings, including wild rice fields, that lie in the path of a new stretch of Line 3, a pipeline bringing nearly 1m barrels of tar sands a day from Alberta, Canada, to Superior, Wisconsin.

But opposition to the pipeline is considerable, andis supported by environmental organizations and activists resisting pipelines such as the Dakota Access pipeline, and Keystone XL – a project that Joe Biden cancelled on his first day in the White House.

The on-the-ground activists are called “water protectors”, who are against the pipeline because of its impact on the climate crisis, oil spills and infringement on Native treaty rights.

There are numerous sites in Minnesota, along the new Line 3 route, where water protectors have set up camp. Much of the route goes through tribal lands, as well as Minnesota’s iron range and areas popular for recreation, including hunting, fishing and people enjoying the outdoors.

It is a lush, wooded part of the state, thick with birch and pine trees, pristine lakes, rolling creeks and lakes filled with wild rice, an agricultural product that is historically significant to the Ojibwe.

Tall grasses poked out of the snow at the spot near the Mississippi headwaters in northern Minnesota, where Houska spoke. “It’s really hard to be in a situation in which we’re looking at this beautiful place and thinking about the fact that our governor has chosen to support or at least tacitly allow a tar sands project, one of the biggest tar sands infrastructure projects in North America,” Houska said. “It’s a perpetuation of cultural genocide.”

A ‘replacement line’ or expansion?

Line 3 is a proposed reroute of a 52-year-old pipeline operated by Enbridge, a Canadian energy corporation based in Alberta. In 2014, after two major oil spills for which Enbridge was responsible, including the largest inland oil spill in US history, the Department of Justice under the Obama administration ordered the replacement line, due to its structural issues. The “replacement” pipeline runs mostly on a completely new route through Minnesota, barreling through hundreds of lakes, rivers, aqueducts and wetlands. It also traverses land that Native American opponents say is protected by US treaties with Ojibwe nations.

For the past three years, Houska, an attorney, has set up camp here with the resistance group Giniw Collective, which she founded. Last week Houska met with the congresswoman Ilhan Omar at the bridge overlooking the river, along with a group of other Native female leaders.

“We need Biden to revoke the water-crossing permit,” Omar told the Guardian. “That is one of the greatest opportunities that can be given to this community.”

Omar sent a letter to Biden calling on him to cancel the permits allowing the pipeline to cross under the river.

Among the objections are that the line will bring an expansion of tar sands, which have higher emissions than other types of crude oil. In addition, opponents say the line is a violation of indigenous territory, as it causes pollution in lands and waters that the Ojibwe were promised to be able to use for ever.

Enbridge calls its $3bn endeavour the Line 3 Replacement Project, claiming the new pipes simply replace existing infrastructure that dates back to the 1960s. But opponents say that it is an expansion not a replacement project, as the majority of the new pipeline in Minnesota takes a different course than the original.

“What I want to say loud and clear is that this is not a replacement line,” said Dawn Goodwin, an Ojibwe advocate from the White Earth reservation, and one of the women who met with Omar at the river. “It’s actually relocation, a whole new project, a whole new corridor.”

The fight against Line 3 evokes a series of treaties signed between the US government and the Ojibwe people, including the treaty of 1837, which explicitly grants the Ojibwe the right to hunt, fish and gather in the lands they gave up, and the 1855 treaty, which in 1999, the supreme court ruled also retains those rights.

More than 100 people have been arrested as they protested against the line in the last month, since construction of the project began, Houska said, but battles are still raging in the courts and between government agencies. In one case, the Minnesota department of commerce claims the utilities regulator should not have sanctioned the project without first evaluating the long-term demand for oil.

Meanwhile, pressure mounts on Biden to halt Line 3 as indigenous activists and environmentalists argue that building new fossil fuel infrastructure will jeopardize his ambitious climate plans.

But not everyone is against Line 3.

‘Preserve our land’

Tim Halberg owns the land on both sides of the river where the pipeline crosses underneath. A research scientist and the proprietor of a land management company, Halberg uses the land to hunt, trap, fish and swim with his family. He grew up four miles north of the crossing, the descendant of Swedish immigrants.

Halberg was approached by Enbridge four or five years ago for permission to use his land for the right of way. He doesn’t see a problem with the pipelines being underground. “The grassland doesn’t get impeded by a pipe in the ground,” he said. “Oil spills are bad, but remember what oil does with water – oil floats. It’s easier to recover.”

Oil pipeline spills are known to happen, like the Kalamazoo oil spill in 2010, in which 1m US gallons of oil flowing through Enbridge’s Line 6B burst into the Kalamazoo River.

Michael Barnes, a spokesperson for Enbridge, said according to the project’s environmental impact statement, Line 3 is unlikely to have much impact on greenhouse gas emissions. “Restored capacity on the replacement line displaces crude oil being delivered today by truck or train, which are more carbon intensive modes of transport,” Barnes said in an email to the Guardian.

Barnes also said that Enbridge has demonstrated “ongoing respect for tribal sovereignty”, pointing to support from the project by both the Leech Lake and the Fond du Lac.

Nancy Beaulieu, an organizer for the environmental group MN350 and a member of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe who met with Omar at the headwaters, is unhappy with how some tribal leaders have accepted the project without consulting their members. This includes the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe – an umbrella organization of the Ojibwe tribes with the exception of Red Lake.

“Being stakeholders of the Minnesota Chippewa tribe, we should have prior informed consent, but we have not,” Beaulieu told the Guardian. “Our Minnesota Chippewa tribe constitution has a preamble to conserve and preserve our resources and our land for the wellbeing of our people and our descendants. Line 3 violates our preamble.”

Others including White Earth, Red Lake and most recently Mille Lacs, have fought Enbridge in court. That fight received a blow this week when the Minnesota appeals court denied a request for a stay of construction. Joe Plummer, a tribal attorney representing Red Lake, said the fight was far from over. “This is only a decision on our emergency request to stop construction,” Plummer said. Oral arguments for the case begin in March, and the tribe has a request in the US district court that challenges the army corps of engineers’ approval.

Another place where the pipeline will cross the Mississippi is near Palisade, Minnesota, in Aikin county. Nearby, a water protector camp called the Welcome Center hosts Natives and allies who want to stand up to Enbridge.

One truth-teller at the site is Tania Aubid, an Ojibwe woman who has no time for elected tribal leaders giving away Native land. “They may have been elected into office, but they don’t know anything about the history of their own people,” she said.

Covid-19 takes the life of the last male from Brazil’s indigenous Juma tribe

The elder Aruká, who died last week in a hospital in the upper Amazon River basin, leaves behind three daughters who are now the only survivors of a group that counted on thousands of members just three centuries ago

Aruká Juma, a native Brazilian, was aged between 86 and 90 when he died from complications caused by coronavirus on Wednesday in an intensive care unit (ICU) in a hospital in Porto Velho, a city located in the upper Amazon River basin, and 120 kilometers by road and two hours by boat from his village.

His death, just like the 1,150 other Covid-19 fatalities registered that day across Brazil, was a tragedy for his next of kin. But Aruká was also the last male from the Juma people, a living memory of ancestral wisdom and a survivor of an attempt to wipe out his kind. The three daughters he leaves behind are now the only ones left from a people who counted on between 12,000 and 15,000 members in the 18th century.

Aruká was the last Juma man who had knowledge of the ways of hunting, the artisan ways of his people

ANTHROPOLOGIST EDMUNDO PEGGION

Acute respiratory failure combined with an infection meant that the senior did not survive the illness, according to digital daily Amazonia Real. As a youngster, he and six other Jumas survived a massacre that was ordered by traders interested in the rubber and chestnuts from his land, according to the detailed information from the Social-Environmental Institute about every one of the hundreds of ethnic groups in Brazil. Hunted down as if they were wild animals, around 60 of the indigenous peoples were killed. It was the last mass-extermination attempt that was suffered by the tribe, which was described by chroniclers as cannibals, perverse and ferocious.

Aruká’s case illustrates how the coronavirus pandemic has affected the indigenous peoples who live in the villages of Brazil, which is the second-worst country in terms of the global impact of the pandemic. Three figures sum up the national drama: 242,000 dead, nearly 10 million infections and a 14% unemployment rate. Among the indigenous peoples who live in villages – a small minority that is particularly vulnerable in this vast territory – Covid-19 has killed 567 people. The life of this Juma offers, what’s more, a look at the history behind these communities that have been decimated since Portuguese colonization and that are essential for the conservation of the Amazon, the biggest tropical jungle in the world. The tribes are key, as such, in the fight to slow down climate change.

Anthropologist Edmundo Peggion came to know the last Juma in the 1990s. “Aruká was the last Juma man who had knowledge of the ways of hunting, the artisan ways of his people,” explains the professor from the Paulista State University (Unesp) via telephone. “There is a consensus in the region, among the Kagwahiva indigenous people, of their importance for the collective memory.” Kagwahiva is the linguistic group to which the Juma belong. “He was recognized as an amóe, a title of respect,” Peggion explains, in reference to a word meaning “grandfather.”

As well as the long-term threats facing Brazil’s indigenous peoples, such as gold miners and illegal loggers, they have also been facing the coronavirus pandemic and Jair Bolsonaro’s handling of the health crisis – the Brazilian president is anti-vaccine, has played down the severity of Covid-19 and has also trampled on the rights of indigenous peoples.

The main associations protecting Brazilian natives have directly blamed the government for Aruká‘s death. “Once again, the Brazilian government has acted with a degree of criminal negligence and incompetence,” they charged in a statement. “The government murdered him.”

The epidemic is spreading fast via the rivers of the Amazon, and the invaders of lands are a source of infection. While vaccines are arriving in remote indigenous villages, there is mistrust of health workers. And the lack of vaccine supply is threatening the campaign in all of Brazil – the program had to be suspended in Rio de Janeiro last week.

Aruká had to be taken to hospital in January and intubated. He became one of the Brazilians to be given what the country’s Health Ministry describes as early treatment, using drugs such as chloroquine – a medication whose efficiency against Covid-19 has not been scientifically proven, and whose usage has been turned into government policy by Bolsonaro.

The death of the indigenous senior “is a devastating loss,” says Edson Carvalho, from the NGO Kanindé. “The history of his life was and will continue to be a symbol of the tremendous fight waged by the Juma people,” he adds, speaking via telephone from Porto Velho, the city where Aruká died.

He will be buried in his village, which is where he was when he noticed the first coronavirus symptoms in January. It’s a place far from any city, a 38,000-hectare indigenous reserve that was created after a long and tough battle that involved years of administrative procedures. The Brazilian authorities were unconvinced as to whether this territory, and its handful of residents, was worthy of the legal protection needed to impede the exploitation of its resources.After another battle with the authorities, Aruká managed to return to the lands where he grew up and where his ancestors lived for centuries

Before this was achieved, at the end of the 1990s the last Juma peoples were removed from their land by the authorities. Aruká, his three daughters, a brother-in-law and his wife were moved against their will to the domain of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, explains Peggion, who had close contact with both groups at the time. There the daughters married men from the other tribe, with whom the Juma had a common language. Abandoning their habitat “had a huge impact in the life of all of the Juma,” the anthropologist explains, adding that the older couple died shortly after the relocation. “In those years, outside of his territory, Aruká was very depressed, he really missed his territory,” the researcher explains.

After another battle with the authorities, Aruká managed to return to the lands where he grew up and where his ancestors lived for centuries. He was accompanied by his daughters (Jumas), their husbands (Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau) and the children of the three couples. The Kanindé NGO claims that the daughters are the last of the line, given that it is the father who passes down the ethnicity. The firstborn, Borehá, is the new chief of the decimated group.

Faithful to his campaign promise, Bolsonaro has failed to give legal protection to a single extra square inch of indigenous land during the two years he has held the presidency. The cases that are being processed have been frozen while the number of Amazon inspectors – the bodies that work to take care of the environment and the indigenous peoples that have protected it for countless generations – is being reduced.

More Native Americans Named to Key Posts in Biden Administration

In a slow rollout of appointments since taking office last month, President Joe Biden has added an additional three Native American members to various department and task force positions in February, making good on “the Biden-Harris commitment to diversity.”

Department of the Interior

On Feb. 3, former attorney at the Native American Rights Fund in Alaska and a tribal member of the Chickasaw Nation, Natalie Landreth, was appointed to serve in the Department of the Interior as deputy solicitor for land.

Landreth will serve under the first Native American cabinet member, Rep. Deb Haaland of New Mexico’s Laguna Pueblo, once the congresswoman is confirmed by the Senate to the secretary of the Interior.

During her 17-year tenure at the Native American Rights Fund, which represents tribes in legal battles over sovereignty, treaty rights and environmental law, Landreth was involved in lawsuits to stop the construction of the Keystone XL Pipeline which Native groups say could pollute sacred lands and waters in Indian Country. Last year, Landreth also successfully challenged Montana’s requirement that mail-in ballots have witness signatures, thereby correcting the most common reason such ballots hadn’t been counted.

Department of Transportation

Navajo Nation’s former Department of Transportation head, Arizona State Rep. Arlando Teller, was appointed last week to serve under department secretary Pete Butigeg as deputy assistant secretary of tribal affairs in the Department of Transportation. Teller is the first openly gay person to be confirmed to a Cabinet post.

He resigned from his legislative seat Jan. 31.

He is the second Navajo person to join the Biden-Harris administration, after Wahleah Johns was selected to serve as Director of the Office of Indian Energy in the Energy Department last month.

President of the Navajo Nation, Jonathan Nez, tweeted that, “Words cannot express how proud we are of these two young Navajo professionals, who have dedicated themselves to serving our Navajo people and are now moving on to the federal level to help empower all tribal nations.”

COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force

On Feb. 10, the White House named 12 members to a COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force.

President Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris created the group “to help ensure an equitable response to the pandemic, the President signed an executive order on January 21 creating a task force to address COVID-19 related health and social inequities,” according to a press release.

Among the 12 member group of diverse backgrounds, Victor Joseph of the Native Village of Tanana in Alaska was selected to serve as a non-federal task force member.

Joseph was elected to Tanana Chiefs Conference Chairman in March of 2014, and served until last October. Prior to that role, he served in various tribal positions, and as Alaska Representative on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Tribal Advisory Committee and the Indian Health Services Budget Formulation Committee.

Indigenous community wins recognition of its land rights in Panama

- A ruling by Panama’s Supreme Court of Justice in November 2020 led to the official creation of a comarca, or protected Indigenous territory, for the Naso Tjër Di people in northern Panama.

- The 1,600-square-kilometer (620-square-mile) comarca is the result of a decades-long effort to secure the Naso’s land rights.

- Panama’s former president had vetoed legislation creating the comarca in 2018, which he said was unconstitutional because it overlapped with two established protected areas.

- Other Indigenous groups in Panama with longstanding comarcas still struggle to hold back outside incursions for projects such as dams and power transmission lines.

The Naso Tjër Di people of Panama now have a protected territory of their own. The creation of the 1,600-square-kilometer (620-square-mile) comarca, as it’s called in Panama, came as a result of a recent decision by the country’s Supreme Court recognizing the Indigenous nation’s land rights.

The court’s decision rested in part on evidence of the role that Indigenous groups play in protecting the environment in Panama, as has been shown elsewhere on the planet, according to an analysis by the Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL).

Leaders in the Naso community have been working toward the goal of a comarca for decades, seeing it as a bulwark against potentially destructive outside incursions.

“Having that official recognition of their land is so fundamental to their well-being and survival as a group,” Sarah Dorman, a staff attorney with CIEL, told Mongabay.

The Naso nation comprises around 4,000 people living in the rainforests of northern Panama along the Teribe River, territory they have lived in for generations. But even as other Indigenous groups in Panama have been able to secure their own comarcas, the Naso’s claim to the land remained unrecognized by the government.

Change appeared to be coming in 2018, when Panama’s National Assembly passed a law to establish the Naso Tjër Di Comarca. Shortly after the vote on the legislation, though, then-President Juan Carlos Varela vetoed it. He said the comarca would overlap with two protected areas designated in the mid-2000s: La Amistad International Park and Palo Seco Protected Forest, both UNESCO World Heritage Sites. As a result, he argued, the legislation creating the comarca was “inconvenient,” “unenforceable” and unconstitutional.

In response, the legislature overrode Varela’s veto, triggering a review of the matter by the Panamanian Supreme Court. The court rejected Varela’s arguments on Nov. 12, 2020, ruling that the Constitution required that the government secure continued collective access for Panama’s Indigenous people to their ancestral lands.

The ruling notes that “the Indigenous population has preserved the environment in the places where they have settled, because they are bearers of ancient knowledge about biodiversity, plants, animals, water, and climate that allows for the sustainable use of the resources available to them,” according to a translation from CIEL.

In another “key reference,” according to Dorman, the court’s members also wrote that Indigenous “laws, customs, and traditional practices reflect both an attachment to the land and the responsibility to conserve it for the use of future generations.”

In a statement following the ruling, the NGO Rainforest Foundation US said its analysis found that less deforestation had occurred on Naso lands than in the Palo Seco Protected Forest.

“As the court says itself, Indigenous peoples are among the best protectors of the environment,” CIEL’s Dorman said.

The court’s decision extended the thrust of a legal memo issued by the Panamanian Ministry of Environment in 2019, saying that protected areas weren’t an impediment to Indigenous land titling.

The Naso Tjër Di Comarca became official on Dec. 4, 2020, when Panama’s current president, Laurentino Cortizo Cohen, went to the town of Sieyik, where the Naso’s king resides, to sign the legislation. In a speech, Cortizo Cohen said the overlap between the comarca and the protected areas would ensure that the forests in the area would be doubly protected, according to a government statement.

Dorman said the recognition of the Naso’s territory is “huge” from a legal perspective. But she also said that more remained to be done to secure their forests.

CIEL works closely with the Ngäbe and Buglé Indigenous peoples in Panama, and these groups achieved a joint comarca in 1997. Dorman said that once a comarca is formed, the law requires demarcating the boundaries between a comarca and adjacent areas within two years.

“That has not been finished to this day,” she said.

In the years since, Ngäbe and Buglé community leaders say they’ve been sidelined for development projects, most recently the construction of a power transmission line through their territory that they worry will force them from their homes.

The Naso have faced their own spate of development projects affecting their lands and fissuring their community. After years of construction on a tributary of the Teribe River, the Bonyik hydroelectric dam came online in 2014, and its social impacts reportedly rippled through Naso communities, according to a World Bank investigation as well as a 2014 report by James Anaya, then the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The dam also lies within the boundaries of the Palo Seco Protected Forest. In fact, human rights groups and Indigenous communities have expressed concern that such protected areas may in fact be a tool to dispossess Indigenous groups like the Naso of their lands to pave the way for lucrative development projects.

Today, the Naso have recognition of their land rights, predicated on their ancestral claims and backed by evidence that shows the group’s superlative environmental stewardship. But until the borders are established, they are still vulnerable from a legal standpoint, Dorman said.

“If your land is not delineated completely,” she said, “it’s just so much harder to legally defend against these outside encroachments.”

Philippines: Drop murder charge against indigenous rights defender, UN experts urge

GENEVA (28 January 2021) – UN human rights experts today called on Philippine authorities to drop a reportedly unwarranted murder charge against an indigenous rights defender who submitted himself to police after a “shoot to kill” order had been issued if he resisted arrest, and to ensure his safety and well-being while in custody.

“From information we have received, Mr Windel Bolinget has been falsely accused of being implicated in a murder of an indigenous leader in a province he has never even been to,” said Mary Lawlor, UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders. “It is believed to be a fabricated charge aimed at silencing him and other indigenous rights defenders and the charge should be dropped.”

The experts said they were seriously concerned for Bolinget’s well-being. “We implore the authorities to ensure he is afforded his right to a fair trial and due process and is not subjected to any harm while in custody,” the experts said, adding that all human rights defenders in the country must be allowed to safely carry out legitimate human rights work without fear of retaliation.

“The practice of levying unfounded charges and accusations against human rights defenders for their peaceful and legitimate work is not only incredibly damaging to these individuals and their families, but also to other human rights defenders and civil society actors in the Philippines,” the experts said.

Bolinget, held in the custody of the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) since 21 January, is an indigenous rights defender and the Chairperson of the Cordillera People’s Alliance (CPA), an alliance of indigenous peoples’ organisations working in the Cordillera region.

A case filed in August 2020 against him and nine others for alleged involvement in the murder of an indigenous leader in 2018 in Davao del Norte province was followed by an arrest warrant for Bolinget in late December. Fearing for his safety, he went into hiding and on 19 January the Cordillera police issued a “shoot to kill” order if he was deemed to resist arrest. Two days later, Bolinget submitted himself to the NBI to ensure his safety and to seek legal assistance to challenge the charges.

The experts said sources close to the victim do not believe that Bolinget or the other accused were responsible for the murder, but rather a paramilitary group that had threatened the victim before his killing.

“The targeting of Mr Bolinget for his work as an indigenous rights defender comes merely weeks after nine Tumandok indigenous leaders were killed and 16 members of the community were arrested in Panay, reportedly in response to their advocacy against the construction of two mega dams and defence of their traditional lands, territories and resources,” said José Francisco Calí Tzay, Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples.

The Special Rapporteurs also expressed concern regarding the recent red-tagging of human rights defenders and staff members of civil society organisations by state officials, including the Commissioner for the Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines (CHRP), Karen Gomez Dumpit, and staff members of the environmental advocacy groups Kalikasan PNE and the Center for Environmental Concerns (CEC). There is a concerning pattern, the experts said, of incidents of red-tagging preceding the killing of a human rights defender.

“Human rights defenders in the Philippines continue to be red-tagged, labelled as ‘terrorists’ and ultimately killed in attempts to silence them and delegitimise their human rights work. This must end.”

The experts are in contact with the authorities on this matter.

Indigenous Lawyer to Lead USDA’s Tribal Relations Office

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced Monday that it has appointed Heather Dawn Thompson, a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, as Director of the Office of Tribal Relations (OTR), which reports directly to the Secretary of Agriculture.

Thompson is a graduate of Harvard law school and “an expert in American Indian law, tribal sovereignty, and rural tribal economic development,” the USDA said in a statement.

Thompson has years of experience working with a number of legal organizations and in public service, including as a member of the American Indian Law Practice Group at Greenberg Traurig, where she focused on federal Indian law and tribal agriculture; a presidential management fellow at the Department of Justice; a law clerk with the Attorney General’s Office for the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe; as Counsel and Policy Advisor to the U.S. Senate’s Democratic Policy Committee; and as assistant U.S. Attorney for the South Dakota’s Indian Country Section, where she worked on cases involving violence against women and children.

She was also a partner at Dentons, where she was one of the few Native American partners at an “AmLaw 100” law firm, the statement said. Additionally, Thompson has served as the director of government affairs for the National Congress of American Indians, president of the South Dakota Indian Country Bar Association, and president of the National Native American Bar Association.

Thompson has a Juris Doctor degree from Harvard Law School, a masters degree in public policy from the University of Florida, and a bachelor’s degree in International Studies from Carnegie Mellon University.

“Heather’s appointment to lead the Office of Tribal Relations is a step toward restoring the office and the position of Director so that USDA can effectively maintain nation-to-nation relationships in recognition of tribal sovereignty and to ensure that meaningful tribal consultation is standard practice across the Department. It’s also important to have a Director who can serve as a lead voice on tribal issues, relations and economic development within the Office of the Secretary because the needs and priorities of tribal nations and Indigenous communities are cross cutting and must be kept front and center,” said Katharine Ferguson, Chief of Staff, Office of the Secretary, in the statement.

“It is an honor and a challenge to serve during these difficult times,” Thompson told the Rapid City Journal. “Here in South Dakota we know better than most that rural Americans have felt frustrated, left out and left behind. And America’s first Americans are often thought of last.”

“We need real systemic economic improvements in Indian Country and in all of rural South Dakota so our children can make a living, so our families can thrive,” she said. “Empowering tribal nations is one of the answers. In other states where rural tribal nations have developed thriving businesses, they are often the largest employers for Natives and non-Natives in their entire region.”

The OTR works on tribal agricultural and economic development, Thompson told the Journal. Under the Trump administration, the OTR was made part of the Office of Partnerships and Public Engagement, but Biden has moved it back to its own office, Thompson said.

According to the USDA, the Office of Tribal Relations “serves as a single point of contact for Tribal issues and works to ensure that relevant programs and policies are efficient, easy to understand, accessible, and developed in consultation with the American Indians and Alaska Native constituents they impact.”

The USDA website says it provides leadership on food, nutrition, agriculture, natural resources, and rural development, as well as public policy surrounding those issues.

“With Thompson in place, USDA will return OTR directly under the Secretary, restoring the office’s important government-to-government role,” the USDA release said.

Joe Biden: ‘Tribal sovereignty will be a cornerstone’

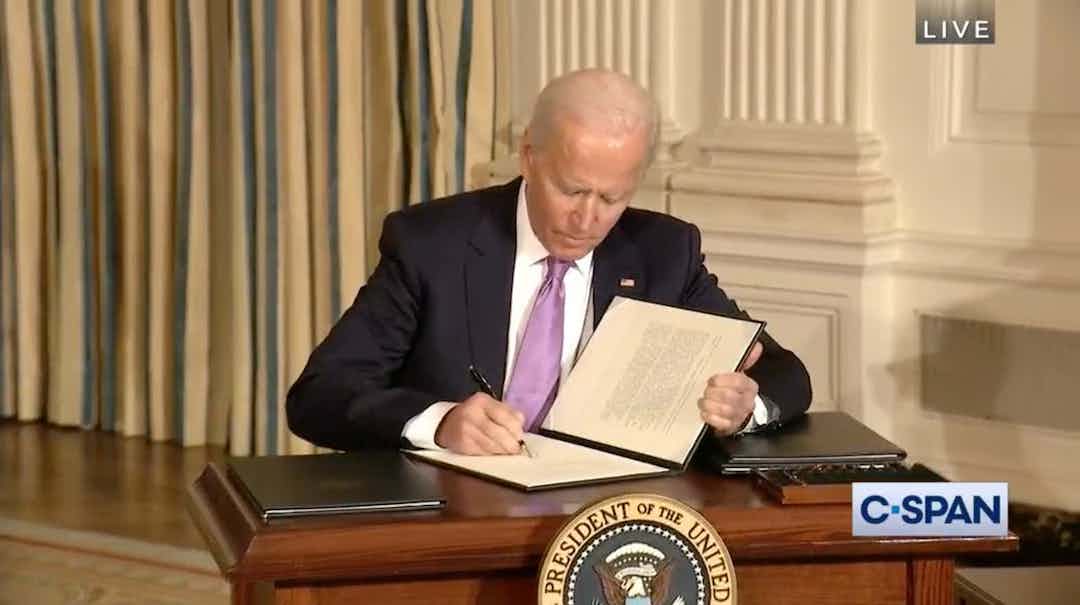

The third of four executive orders signed by President Joe Biden on Tuesday focuses on strengthening the nation-to-nation relationships with tribes. It’s only one presidential action of many taken by the administration in week one.

Biden signed a presidential memorandum that requires all federal agencies and executive departments to have a “strong process in place for tribal consultation,” said Libby Washburn, Chickasaw and the newly appointed special assistant to the president for Native American Affairs for the White House Domestic Policy Council. The position previously was held by Kim Teehee, Cherokee, and Jodi Archambault, Hunkpapa and Oglala Lakota, in the Obama Administration.

The move represents the new president “committing to regular, meaningful robust consultation with tribal leaders” and it requires all federal agencies and executive departments to have a “strong process in place for tribal consultation,” Washburn said.

Biden gave remarks on his racial equity plan, which includes the signed tribal consultation memorandum, from the White House State Dining Room.

“Today I’m directing the federal agency to reinvigorate the consultation process with Indian tribes,” Biden said, noting respect for sovereignty “will be a cornerstone of our engaging with Native American communities.”

Washburn said previous presidents like Barack Obama and Bill Clinton have done this.

So what makes this one different?

It enforces a previous tribal consultation executive order signed on Nov. 6, 2000.

This time around the executive order requires the head of each agency to submit, within 90 days, a memorandum with a detailed plan of action on how they will implement policies and directives, Washburn said. Agencies must listen to what tribes want.

These federal agencies and executive departments will have to continuously keep the White House updated, she said.

Tribal consultation is also crucial when it comes to the pandemic.

“This builds on the work we did last week to expand tribes’ access to the Strategic National Stockpile for the first time, to ensure they receive help from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, FEMA, to fight this pandemic,” Biden stated Tuesday.

On Jan. 21, Biden announced that FEMA would make financial assistance available to tribal governments at 100 percent of the federal cost share.

When the COVID-19 pandemic was declared a national emergency, it activated eligible tribal, state and local governments to access FEMA emergency funding, Washburn said. The federal cost share was 75 percent, and tribes were responsible for 25 percent of the cost.

“It has been something the tribes have been asking for, for a long time, and there has been legislation pending in the House and Senate on it,” Washburn said.

The funding can be used for safe openings, operations of schools, childcare facilities, health care facilities, shelters, transit systems, and more.

Another ask by the tribes: access to the Strategic National Stockpile. And granted by the administration on Jan. 21.

The public health supply chain executive order states that the “Secretary of Health and Human Services shall consult with Tribal authorities and take steps, as appropriate and consistent with applicable law, to facilitate access to the Strategic National Stockpile for federally recognized Tribal governments, Indian Health Service healthcare providers, Tribal health authorities, and Urban Indian Organizations.”

Fawn Sharp, Quinault, president of the National Congress of American Indians, said the administration’s first week demonstrated that the needs of tribal nations are a priority.

“I am both excited and encouraged that the Biden Administration is taking so many meaningful and significant steps towards Tribal Nations’ priority issues — respect for sovereignty, racial equity, urgent action on climate change, protection of sacred sites and ancestral ecosystems, and the commitment to meaningful Tribal consultation,” she said. “There’s immense work still to be done, but we celebrate that the first steps President Biden has taken towards truth and reconciliation with Tribal Nations are so responsive to our needs and aligned with our values and principles.”

Since Day One, the Biden administration has gone full speed on taking presidential actions that affect tribal nations.

Hours after taking his oath, Biden revoked the permit for the Keystone XL pipeline, placed a temporary moratorium on all oil and gas activities in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and signed another executive order on “advancing racial equity and support for underserved communities through the federal government.”

“I think it’s exciting and it shows that things are going to be front and center for him and his entire administration,” Washburn said, adding that includes hiring more Native people across the board.

In addition to New Mexico Rep. Deb Haaland’s nomination for Interior secretary, Washburn said, “President Biden, he promised during the campaign that tribes would have a seat at the table at the highest levels of federal government and a voice throughout the government, and I think that he’s really showing in the early beginning days of his administration that he is going to make sure that happens.”

And down to what is in the Oval Office. Washburn pointed out that a painting of Andrew Jackson, a strong proponent of Indian removal, was removed from the Oval Office. The “Swift Messenger” sculpture by Allan Houser, Chiricahua Apache, now sits on a bookcase, reported the Albuquerque Journal.

As for land acknowledgements, that’s an ongoing conversation.

“It is something that we are talking about, so I think we will talk about it and really, I’d like to talk to Deb Haaland about it as well, and once she’s confirmed it’s something that I think will become a focus,” Washburn said.

President Joe Biden rejoins the Paris climate accord in first move to tackle global warming

President Joe Biden signed an executive order to rejoin the U.S. into the Paris climate agreement on Wednesday, his first major action to tackle global warming as he brings the largest team of climate change experts ever into the White House.

The Biden administration also intends to cancel the permit for the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline from Canada to the U.S. and sign additional orders in the coming days to reverse several of former President Donald Trump’s actions weakening environmental protections.

Biden vows to move quickly on climate change action, and his inclusion of scientists throughout the government marks the beginning of a major policy reversal following four years of the Trump administration’s weakening of climate rules in favor of fossil fuel producers.

Nearly every country in the world is part of the Paris Agreement, the landmark nonbinding accord among nations to reduce their carbon emissions. Trump withdrew the U.S. from the agreement in 2017.

Mitchell Bernard, president of the Natural Resources Defense Council, said Biden’s order to rejoin the accord makes the U.S. part of the global solution for climate change rather than part of the problem.

“This is swift and decisive action,” Bernard said in a statement. “It sets the stage for the comprehensive action we need to confront the climate crisis now, while there’s still time to act.”

With a slim Democratic majority in the Senate, Biden could potentially achieve large parts of his ambitious climate agenda, including a $2 trillion economic plan to push forward a clean-energy transition, cut carbon emissions from the electricity sector by 2035 and achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

During his first few months in office, Biden is expected to sign a wave of executive orders to address climate change, including conserving 30% of America’s land and waters by 2030, protecting the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge from drilling, and restoring and elevating the role of science in government decisions.

Some legal actions on climate will take longer, including the administration’s plan to reverse a slew of Trump’s environmental rollbacks on rules governing clean air and water and planet-warming emissions. The Trump administration reversed more than 100 environmental rules in four years, according to research from Columbia Law School.

“From Paris to Keystone to protecting gray wolves, these huge first moves from President Biden show he’s serious about stopping the climate and extinction crises,” Kieran Suckling, executive director of the Center for Biological Diversity, said in a statement. “These strong steps must be the start of a furious race to avert catastrophe.”

The next major U.N. climate summit will take place in Glasgow, Scotland, in November. Countries in the agreement will give updated emissions targets for the next decade.

A goal of the agreement is to keep the global temperature rise well below 2 degrees Celsius, or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, compared with preindustrial levels. The Earth is set to warm up by 1.5 C, or 2.7 F, over the next two decades.

Robert Schuwerk, executive director for North America at Carbon Tracker, said rejoining the accord signals to global markets that the U.S. will make tackling climate change a priority, but added that it’s only a part of what the administration must do to lower its emissions.

The U.S. is the world’s second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases behind China. It’s expected to have an updated climate target and a concrete plan to reduce emissions from the power and energy sector.

“Rejoining is just table stakes,” said John Morton, who was President Barack Obama’s energy and climate director at the National Security Council. “The hard work of putting the country on a course to becoming net zero emissions by mid-century begins now.”

The Amazon is Dirty, Our Rivers and Fish are Contaminated, Everyone is Sick

“The Amazon is dirty, our rivers and fish are contaminated, everyone is sick. We no longer feel safe in the forest, in our home.” — Alessandra Munduruk, Munduruku Mother

The Yanomami, Munduruku, and Kayapo Peoples share how the Bolsonaro government is worsening their situation and threatening the forest and human rights in Brazil in this three part article series. Part one focuses on Yanomami Peoples.

At the beginning of December 2020, Brazil’s Congresswoman Joenia Wapichana, the Joint Parliamentary Front in Defense of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the Parliamentary Environmental Front organized a webinar with politicians and civil society to hear testimonies of three Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon on their current realities.

After the event, I connected with members of the mentioned Peoples who shared more in detail about what is happening on the ground in Brazil. One of the speakers connected me with the public prosecutor, the equivalent of a district attorney, who divulged important documents about illegal mining activities on Yanomami lands.

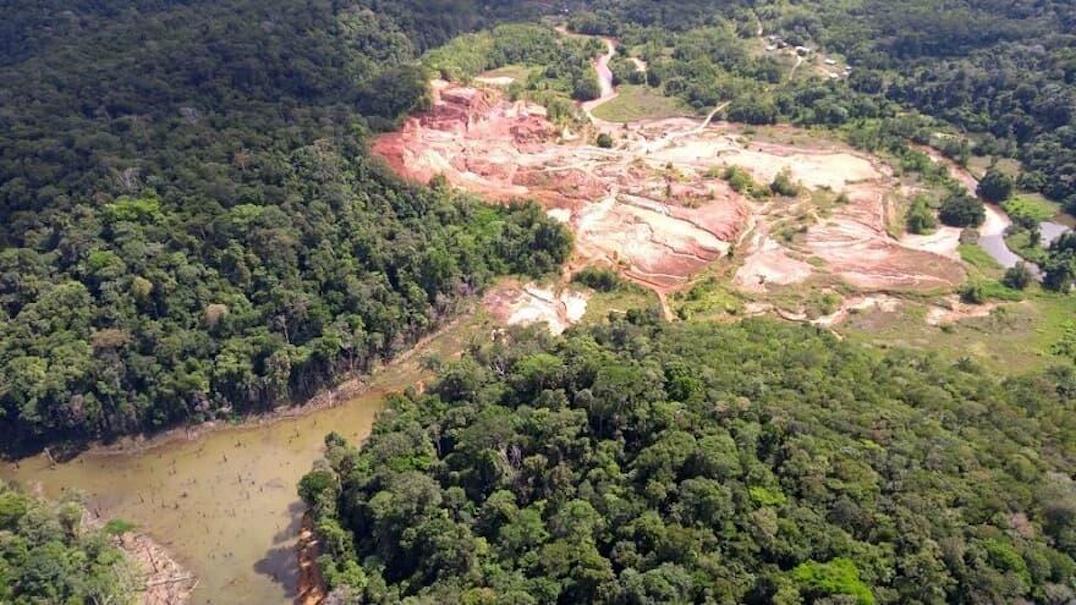

This article focuses on five issues related to the violation of Indigenous Peoples’ rights and the destruction of their lands in the Brazilian Amazon: the invasion of Indigenous lands; the contamination of soil, rivers, fish and communities with mercury; diseases and health problems, such as infertility, resulting from malnutrition; high consumption of drugs and alcohol, brought by prospectors, affecting Indigenous communities; dismantling of agencies and institutions that protect forests and Indigenous communities, such as local Indigenous health posts, environmental protection bases, and policing and monitoring of territories.

The Yanomami Report

The small Yanomami village of the Kayanaú community, near the Mucajaí River in the Rio Negro basin, numbers about 200 people who are dealing with a contingent of more than 1,600 illegal prospectors on their lands.

An airstrip for small aircrafts was built in their territory in the state of Roraima, the country’s far north region bordering Venezuela. The track that once received health personnel and environmental and border protection agencies was taken over by illegal miners. The frequency of flights of airplanes and helicopters to supply the mine is now more than 50 per week. This heightened number has alerted the team of healthcare officers who visited the Indigenous community during a health and vaccination check in. The planes bring more prospectors, alcoholic beverages, and even drugs to the site weekly. Not only do they land with their fleet, but miners wander around the villages in armed groups, travel the rivers by boat, and settle in strategic places to establish illegal mining sites. These people not only offer Yanomami goods and money, disrupting their traditional economies, but also introduce individuals to drugs, alcohol, even prostitution to coerce the local community as a labor force. Without legal, environmental and even special protections such as consent protocols, State monitoring, and insufficient healthcare, the negative impacts on the Indigenous livelihoods are quickly felt.

The medical team and the prosecutor who are monitoring the situation without resources told me that they found “Indigenous people constantly drunk and that women, children, and adults walk through the woods with alcohol at all times. That’s why they’re refusing medical treatment.”

In addition, the practice of semi-slavery of Indigenous Peoples in the region is prevalent, because, after creating drug and alcohol dependency, the community no longer wants to practice traditional activities, such as agriculture, hunting, and gathering. In exchange for drugs, alcoholic beverages, and prostitution, they go to work for the prospectors. The medicine, vaccinations, and resources intended for the Yanomami were taken by the miners, leaving the Indigenous People completely unprotected, sick and vulnerable.

Moreover, the situation is even more alarming with regard to violence at various levels. The monitoring medical team is afraid of retaliation and threats from prospectors if they release their report which shows how the miners, employed corporations whose names and affiliations are never revealed, install a structure of scaffolds along the rivers, to support and protect their illegal activities. The region has been abandoned by the State.

Dário Kopenawa, son of prominent Indigenous leader, thinker, and author of The Falling Sky – Words of a Yanomami Shaman, David Kopenawa, reveals that, despite all the visibility that the Yanomami people have, the Brazilian government has done nothing to stop the invasions and illegal mining on their lands. Yanomami associations are raising the visibility of this issue and have collected more than 439,000 signatures from people in Brazil and abroad in a petition demanding the removal of 20,000 illegal prospectors in the Yanomami territories.

The mining, beyond causing the degradation of rivers and forests, and undermining the rights and protections of Indigenous Peoples, has caused serious health issues for communities near and far. The miners, prospectors and their entourage are the main sources of transmission of the new coronavirus, and other diseases, such as STDs, and the flu. A total of 1,202 Yanomami were infected by COVID-19 and 23 have died, according to a report produced by the Yanomami and Ye’kwana Leadership Forum.

The lands of the Yanomami are located in two states in the north of the country, Roraima and Amazonas. They are neighbors to the territories of the Munduruku and Kayapo Peoples, who are also facing a systematic invasion of their lands and are endangered by genocide and unprecedented environmental impacts.

The Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information, or Raisg, in their report entitled Looted Amazon (Amazonia Saqueada), shows that there are more than 2,500 mining sites in the Amazon region, comprising areas in Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela. The report also shows the general routes going in and out of mining areas in the region as well as the impacted rivers and Indigenous lands by illegal practices.

If a mining station accommodates an average of 1000 people, it is not difficult to conclude that the Amazon today has never been more in danger. With the high price of gold on the international market, the practice of mining has intensified even more during the COVID-19 pandemic, which in turn increases the human rights violations against Indigenous Peoples.

Given this situation, protection agencies as FUNAI, the federal police, and IBAMA– the federal agency of monitoring and protection of the environment, have seen their budgets cut dramatically. In the case of FUNAI, its mission has been changed profoundly, “from an Indian affairs agency to a State agency against Indigenous Peoples,” as described by Alessandra Munduruku, a Indigenous activist from Munduruku people.

In addition, the Brazilian government has insisted on implementing unconstitutional laws and influencing public opinion to serve the interests of mining companies. According to the website Amazonia Legal and E. de Sao Paulo newspaper, a survey reveals that 145 applications for mining permits were filed with the National Mining Agency by November 3, 2020, the highest volume in 24 years.

A bill formulated by Brazilian President Bolsonaro in February 2020 aims to legalize mining activity on Indigenous lands and is currently sealed by the Brazilian Constitution. In September, the government launched the Mining and Development Program, which cites its goals as “promoting the regulation of mining on Indigenous land, granting of mining titles, stimulating the implantation of mining sites, and fostering geological research of mineral goods considered a priority for the country.”

Despite being unconstitutional, the National Mining Agency (ANM) maintains the requests of more than 3,000 applications to mine on Indigenous lands (IT) in the Amazon, as the Looted Amazon report reveals. Any mining activity, even research and prospecting, is prohibited by Brazil’s Constitution in these areas, but Indigenous Peoples have witnessed that leveraged by the federal government, every month, dozens of new requests are filed and accepted. All these actions multiply the problems that Indigenous Peoples in Amazon are facing.

On the day before Christmas, the Coogal Union of Miners in the north of the country in Lourenço, a region near Roraima and Para, where the Yanomami, Munduruku and Kayapo Peoples live, managed to reverse a court decision on the suspension of old extraction activity as well as the dissolution of the entity for its illegal and risky activities. However, the judge of TRT-8, the regional labor court, Luís Ribeiro saw serious social impact implications to families living in the region. The Union has more than 900 members whose families also live in the area. This is yet another example of how the situation, unresolved by the government, creates an avalanche of social, environmental, and legal problems.

In June 2020, representatives of Yanomami associations organized a conference with the Vice-President of the Republic, Hamilton Mourão, with Congresswoman Joenia Wapichana. He received the document with evidence of the illegal mining activities and a formal petition for the removal of the miners. According to Dario Kopenawa, Vice-President Mourão said, “Ah, Dario, the Yanomami territory is very large, the federal government does not have the resources to pay employees, has no planes, logistics are difficult [to protect the area]. I worked in São Gabriel da Cachoeira, I know the region.”

Then, on his Twitter account, the Vice-President said that the number of prospectors on Yanomami lands is 3,500 and not 20,000, as estimated by Indigenous organizations. This attitude of disrespecting Indigenous Peoples and trying to delegitimize their cause has been commonplace in the current administration. Still, the second man in the government has promised a plan to remove illegal prospectors from Indigenous lands. So far, nothing has happened.

This situation is not only an example of the problems faced by Indigenous Peoples, but the Brasileiro State, in its deadly incompetence, does not offer environmental protection, prevent social and cultural conflicts in the region, or guarantee a healthy environment for vulnerable citizens. The rights to life, integrity, culture, property, freedom, according to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, through Consultative Opinion (OC) 23/17, has a strong interdependence with the environment environment and sustainable development, in other words, that human rights are fully satisfied only if a “minimum environmental quality” is respected.

Indigenous Peoples in Brazil want the world to know that their rights are being violated on their own territories. The Brazilian State is violating their rights to a healthy environment and therefore their rights to to life, health, food, water, sanitation, property, private life, culture, and non-discrimination, among others. There is a profound relationship between the rights of Indigenous Peoples and the rights of Nature and its protection. The destruction of such a large area, larger than many countries in Europe, has a significant impact on the environmental relations on the planet, worsening the effects of climate change which affects everyone, Indigenous or non-Indigenous.

A fighting generation of the Yanomami, as well many Indigenous Peoples in Brazil, have suffered devastating losses in 2020 due to COVID-19. “Our Grandmothers are dying. We want to live in peace. We want our land in peace, without the presence of prospectors. Our relatives, the fish and animals are dying of mercury. Our land is already demarcated. The Constitution has very beautiful words about our rights, but in practice this is not what happens,” concludes Dario Kopenawa.

The request is simple and clear: “Remove Miners from Our Lands!”

— Edson Krenak Naknanuk is an Indigenous activist and writer in Brazil and a consultant at Cultural Survival. Currently, he is a Ph.D. candidate in Social and Cultural Anthropology with studies in Legal Anthropology at Vienna University, Austria. He is also a teacher of languages and humanities. He loves interacting with children and youth and preparing them for a better world.

Biden signals plans to halt oil activity in Arctic refuge

U.S. Bureau of Land Management in Alaska waits for guidance on presidential order

President Joe Biden’s administration announced plans Wednesday for a temporary moratorium on oil and gas leasing in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge after the Trump administration issued leases in a part of the refuge considered sacred by the Indigenous Gwich’in.

The plans, along with other executive actions, came on Biden’s first day in office.

Issuing leases had been a priority of the Trump administration following a 2017 law calling for lease sales, said Lesli Ellis-Wouters, a spokesperson for the U.S. Bureau of Land Management in Alaska.

The agency held the first lease sale for the refuge’s coastal plain on Jan. 6. Eight days later, Ellis-Wouters said, it signed leases for nine tracts totalling nearly 1,770 square kilometres. The issuance of leases was not announced publicly until Tuesday, President Donald Trump’s last full day in office.

No official guidance yet

Ellis-Wouters said by email Wednesday that she has not “received anything on executive orders that pertain to the ANWR lease sales.”

E. Colleen Bryan, a spokesperson for the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority, said the state corporation, which was issued seven leases and was the main bidder in the lease sale, “can’t speculate what may happen with the new administration.”

‘Alleged illegal deficiencies’

Biden has opposed drilling in the region, and drilling opponents hope the executive action is a step toward providing permanent protections, which Biden called for during the presidential campaign.

His order cites “alleged legal deficiencies” underpinning the oil and gas lease program in calling on the Interior secretary to, “as appropriate and consistent with applicable law, place a temporary moratorium on all activities of the Federal Government” related to implementing the program. The order also calls on the secretary to review the program and potentially conduct a “new, comprehensive” environmental review.

Pending lawsuits challenge the adequacy of the environmental review process undertaken by the Trump administration.

Decades-long fight

The fight to open the coastal plain to drilling goes back decades, with the state’s Republican congressional delegation hailing the issuance of leases as “significant and meaningful for Alaska’s future.” They criticized on Wednesday the planned moratorium.

U.S. Senator Dan Sullivan said in a statement that Americans did not give Biden “a mandate to kill good-paying jobs and curry favour with coastal elites.”

U.S. Senator Lisa Murkowski said “significant progress” has been made in the past month, with the lease sale and issuance of leases.

“The Biden administration must faithfully implement the law and allow for that good progress to continue,” she said in a statement.

Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy, a Republican, said the state “does responsible oil and gas development in the Arctic better than anyone, and yet our economic future is at risk should this line of attack on our sovereignty and well-being continue.”

Oil has long been the economic lifeblood of Alaska, and drilling supporters have viewed development as a way to boost oil production that is a fraction of what it was in the late 1980s, and to generate revenue and create or sustain jobs.

Drilling critics have said the area off the Beaufort Sea provides habitat for wildlife including caribou, polar bears, wolves and birds — and should be off limits to drilling. The Gwich’in have raised concerns about impacts on a caribou herd on which they have relied for subsistence.

“It is so important that our young people see that we are heard, and that the president acknowledges our voices, our human rights and our identity,” Bernadette Demientieff, executive director of the Gwich’in Steering Committee, said in a statement.