Mobilization, Low Life Expectancy, and Extremism: Key Highlights on Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Russia from the UN Special Rapporteur’s Report

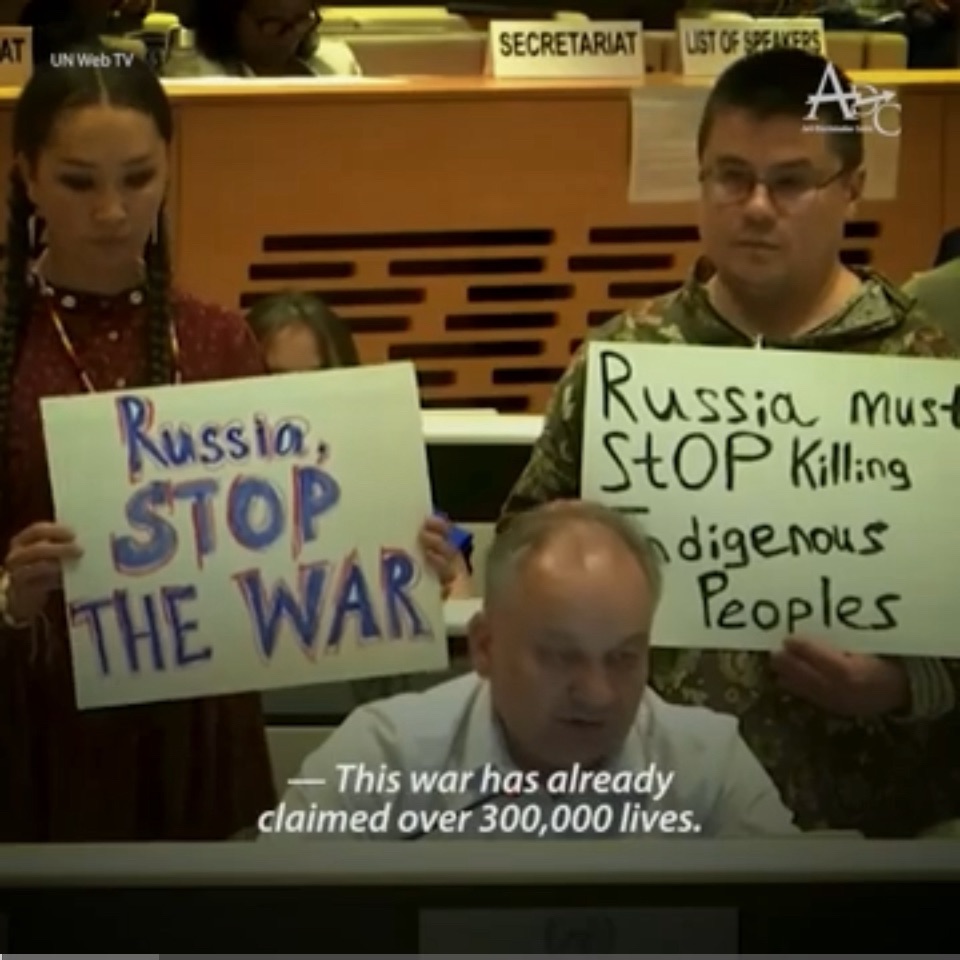

Mariana Katzarova, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Russia, delivered a report on the state of human rights in the country during the 57th session of the United Nations.

Katzarova highlighted the harsh suppression of protests by ethnic minorities and Indigenous peoples in Russia, particularly demonstrations advocating for environmental rights. She referenced the persecution of activists in Bashkortostan as an example. Among the political prisoners, she cited Yakut shaman Alexander Gabyshev, who was sentenced to forced psychiatric treatment for his “pilgrimage against Putin.”

The report also mentioned the designation of the fictitious “Anti-Russian Separatist Movement” as an extremist group, followed by the classification of 55 independent Indigenous organizations, including those from the Arctic regions, as “extremist.”

RAIPON (Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North), which officially handles the rights of Indigenous peoples in the Arctic, was involved in adding these groups to the extremist list. However, RAIPON has been criticized for acting as a government policy tool and lobbying large companies. This was documented in an investigative report by “Arctida,” in collaboration with “Verstka.”

Katzarova noted that Russia’s mobilization efforts for the war disproportionately target Indigenous peoples and individuals who recently gained Russian citizenship — mainly migrant workers. According to Katzarova, “this poses an existential threat to some small Indigenous groups due to the heavy military losses they have sustained.” Russia does not disclose the ethnic breakdown of its military casualties, nor does it publish overall casualty figures.

She also pointed out that Indigenous peoples in Russia suffer from some of the lowest life expectancy rates in the country. Despite this, the Russian government continues to reduce subsidies and impose restrictions on their access to support, particularly through the registry of small Indigenous peoples. Katzarova called on the Russian authorities to end the discrimination and violence against Indigenous communities and urged UN member states to support those being persecuted in Russia.

The mandate for the UN Special Rapporteur on Russia was established on October 7, 2022, and is held by Bulgarian human rights advocate and Amnesty International representative Mariana Katzarova. Russia does not recognize this mandate and has denied Katzarova entry into the country.

Sourced from arctida.io

The Russian State Duma was asked to protect the lands of the indigenous peoples of Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug (KhMAO) from oil developers.

Representatives of the “Public Radar” project asked the State Duma of the Russian Federation to protect the lands of the indigenous peoples of KhMAO from oil developers.

On January 24, 2024, Surgutneftegaz offered the indigenous residents of the Surgut region of KhMAO compensation for oil extraction on their land. The company wanted to pay locals for their lost profits from the sale of berries and animal skins, which they harvest on the territory needed by Surgutneftegaz.

According to a representative of the human rights project “Public Radar,” people refused the compensation at a meeting with the company, considering it too low. In March, Surgutneftegaz began oil production.

Human rights defenders discovered that, by law, oil companies are not required to pay compensation to small indigenous peoples engaged in traditional activities. This is due to a gap in the law: the registries of the indigenous population and traditional land use territories are not synchronized.

— Usually, if families do agree [to compensation], the oil companies may occasionally purchase equipment for hunting and northern life (snowmobiles, boats, gear) for them, but this is done voluntarily, without any contracts, — said “Public Radar.”

Human rights defenders submitted their ideas for legal amendments to Oleg Mikhaylov, a State Duma deputy from the Communist Party (KPRF). They propose simultaneously entering data into both registries, prohibiting oil companies from calculating compensation for residents based on the cost of skins and berries, and suspending companies’ operations if they extract resources without consent.

On April 29, 2024, it became known about the death of Sergey Kerimov, the last defender of the lake sacred to the Khanty people. He died of cancer. The man fought against oil extraction by Surgutneftegaz near Lake Imlor. He tried to defend his encampment and was forced to relocate more than 20 times at the oil company’s request, freeing up land for them.

The activist was tried three times: in 2017, he was sentenced to community service for threatening Surgutneftegaz, and in 2022, he was given six months of restricted freedom. In December 2022, Kerimov had a conflict with the police, after which he was charged with using violence. Tuvan journalist Sayana Mongush wrote that Kerimov’s underage son was killed in a car accident by drunk oil workers.

Presentation for the session “Mapping Indigenous Peace-building Today : Research and Policy.” April 11, 2024 Institute of Peace First Global Summit on Indigenous Peacebuilding

“Action Anthropology, Indigenous Rights and Changing Agendas in Siberia”

Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer, Georgetown University balzerm@georgetown.edu

Introduction

In the 1990s, Siberian leaders and First Nations activists learned from each other through MacArthur Foundation cultural exchanges in Russia, the US, and Canada that I helped organize. It was an early effort at international peace strategizing, focused on defending and protecting Indigenous rights to land and resources. This Institute of Peace Summit continues that legacy in a bigger way in these perilous times. The mantra of ‘nothing about us without us’, spreading globally among Indigenous communities in the 20th century, has led to reassessments of how educated Indigenous leaders interact with those who come to study their societies. Basic respect and rapport centred on what issues local communities themselves consider urgent are keys to new approaches to research and policy, especially concerning war, interethnic tensions and peace building. Burning concerns in Siberia, in the context of Russia’s increasingly dangerous and destabilized society, include: “Who owns Native culture?”, “Can protests help peace efforts?” , and “How do intertwined and economically dependent Indigenous communities become post-colonial?”

The most rewarding of my fieldwork in the republics of Sakha, Buryatia and Tyva has been collaborative, including co-authorship and co-theorizing, especially with one of the founders of ethnosociology in Sakha Republic — Uliana Vinokurova. Uliana in the post-Soviet period was a member of the Sakha parliament, called Il Tumen, “Meeting for Agreement”, itself a notable marker of Indigenous consensus values. She’s a well-known Sakha defender of the republic’s over seven Indigenous communities and was a speech writer for the first post-Soviet Sakha president of the republic. As one of the authors of the republic’s sovereignty- oriented 1992 Constitution, she participated in one of the early post-Soviet efforts at bringing democracy to her republic, in the process blowing all sorts of stereotypes about Indigenous peoples. The professionally diverse members of the committee spent a year reading every constitution they could to choose how they wanted to construct their own state-within-a-state. For Uliana, peacebuilding with Moscow was based on ideals of nested sovereignty, non-chauvinist nationalism for everyone, and negotiated, real federalism. One of her important lessons has been: “Never declare separatism or independence for anyone until they do so themselves.” However, in the context of Russia’s aggressive war against Ukraine, and the disproportionate mobilization of non-Russian Siberians to fight and become cannon fodder, some Indigenous Siberians are indeed becoming independence minded, are reconfiguring definitions of civil war, and are fleeing Russia into increasingly politicized Siberian diasporas.

Background for post-Soviet Indigenous Research and Policy Empowerment

In Russia in the 1990s, the activist group RAIPON [Russian Association of the Indigenous Peoples of the North] was able to help shape pressing legal and research agendas, but after 2011 it was disempowered.[1] This sad history is appropriately told by one of the key activists, Pavel Sulyandziga, then-Vice-President of RAIPON, who is present at our Summit. A collaborative community monitoring Indigenous rights and urbanization trends has been exemplified by Pavel Sulyandziga, Mikhail Todyshev, and Ol’ga Murashko (2002), Rodion Sulyandziga, Dmitri Berezhkov, and the work of Russian legal anthropologist Natal’ia Novikova with Nenets scholar Yelizaveta Yaptik (2018). Sensitivity to changes in Russian laws and to issues of cultural appropriation was also reflected in anthropology of Siberia projects funded internationally during and after Soviet Union disintegration. Legal, economic, and ‘action’ anthropology, including issues of ecology, sovereignty, identity, and de-escalation of interethnic conflict characterized a range of collaborative projects sponsored by the MacArthur Foundation and the U.S. National Science Foundation.[2]

Among the most sensitive issues are contested sacred lands, especially sacred burial grounds. In addition to dangers of non-consensual industrialization, climate change, forest fires, and earthquakes, threats from archeologists loom large in many Indigenous worldviews. All have converged in the Altai, where the renowned Scythian (Pazyryk) mummy of a resplendent female was discovered in 1993 on the Ukok Plateau. Indigenous protests have galvanized local communities against the unearthing of the ‘Altai princess’, her scientific examination in multiple countries, and her museum incarceration in Gorno-Altaisk, in a glass-enclosed pseudo-tomb, most outrageously paid for by the state-affiliated energy company GAZPROM.[3]

Collaborative Work with Uliana Vinokurova

Concerns about the shifting dynamics of self-determination, identity and interethnic peace have dominated my work with Uliana. One year, while in Alaska on one of the MacArthur Foundations exchanges, I asked her what she thought my fieldwork focus for the next summer should be. She quipped “why don’t you find out why these pesky Evangelical missionaries from the US think there’s a spiritual vacuum in our republic?”

Uliana was born into a large, loving, hospitable Sakha family in the northern region of Sredniaia Kolyma, in a village of Sakha, Yukaghir, and Ėveny. Her education in psychology and sociology served as springboards for a worldview she calls ‘ecosophy’ and advocacy for what she terms Indigenous methodology.[4] When she twice won as deputy to the Il Tumen(1992-2003), some in the republic perceived her as Ėvenki, or as mixed ethnic, in part due to her vigorous defense of legislation promoting the economic well-being of ‘small-numbered’ peoples in the Sakha Republic. When occasionally she was called a ‘Yakut (Sakha) nationalist’ in Moscow, Uliana countered any false impression of chauvinism with charm and humour, saying ‘all Russians are welcome in our republic, as long as they treat her as a mother to be cherished and not a mother-in-law’.[5]

In the chaotic emergence of debates about nationalism and transparency over ethnic tensions, the MacArthur Foundation project ‘Ethnic Conflict in the post-Soviet World’ was created and led on the Russian side by Leokadiia M. Drobizheva.[6] At my request, Uliana and I were matched for a 1993 Prague conference and 1996 book. We saw the Sakha Republic (Yakutia) as a major ‘swing’ territory (one-sixth of Russia), of enormous diamond and other mineral wealth with sustainable development potential, that could become unstable or could emerge from Soviet-style resource-extraction colonialism into a multi-ethnic federal republic (Balzer & Vinokurova 1996).

We argued that to stabilize the society, past interethnic tensions needed to be exposed and analysed rather than propagandized out of existence with ‘brotherhood of the peoples’-type slogans. Given Chechnya’s declarations of secession, and Tatarstan’s unrest, some outside analysts were overgeneralizing about domino-like secession movements in Russia. Uliana explained that the Sakha Republic could ill-afford to secede and risk the well-being of ‘already ailing Northern Natives’, the Ėveny, Ėvenki, and Yukaghir. She declared Russian-led regions deserved as much self-rule as ethnic-based republics, and that Russia could be viable with multi-leveled patriotism in a matrioshka federal state structure. Fascinated by Yael Tamir’s (1993) concept of ‘liberal nationalism’, she also insisted that ‘for many, the appetite for greater sovereignty has grown in the eating’, and that the republic’s peoples had the right to their own constitution, passed before Russia’s was ratified.[7]

Our activist anthropological approach, which included trends in Sakha cultural revival politics, was meant to balance the rights to cultural assertion and self-rule, a degree of sovereignty, with understanding of economic and strategic realities inherent in negotiated federalism. We presaged the concerns of a budding ecology movement by warning that a ‘psychology of immediate gratification has led to terrible ecological destruction in mining and lumbering areas and to ethnic tension’, and we concluded that ‘the best antidote against virulent forms of nationalism is a well-managed federalism’ (Balzer & Vinokurova 1996: 164, 173).

Reflecting many years later on the anniversary of the 1992 Sakha Constitution ratification, a jubilant moment in Sakha history when celebrants poured onto Yakutsk streets, Uliana explained that despite the unfulfilled hopes for greater sovereignty after 2000, the 1990s represented an important period when Sakha were able to better understand their history of self-awareness as a people with legacies of literacy and leadership dating to the early 20th century. ‘The value of sovereignty itself became a spiritual basis for the self-identity of the Sakha people’ (email, 12 December 2021).

Anti-war Activism and Peace-building

Since February, 2022, when Russia’s army invaded Ukraine in a full-scale illegal attempt to absorb a neighboring country, conditions for Indigenous Siberians have worsened considerably. They were already among the poorest, and thus most likely to be tempted by higher salaries offered by the army. When the war began, non-Russians were mobilized in high numbers, trained inadequately, forced to provide their own equipment and clothing, and sent to the front lines. Consequent casualty rates have resulted in highly disproportionate numbers of Siberians being killed in Eastern Ukraine.[8] This is shown by a well-researched BBC/Mediazona map indicating first year casualties [9] that reveals Tyvans, Buryats and Sakha, to be the groups with the highest mortality rates. In contrast, Moscow and St Petersburg have less than 0.7 deaths per 100,000. The map uses official statistics; actual casualty numbers of minorities are even higher. The pace of non-Russian, especially Buryat, deaths has accelerated since then.[10]

Siberians such as Buryats and Tyvans often combine Buddhist values with beliefs inherited from pre-Buddhist and pre-Christian spiritual values and upbringing.[11] These Buddhist and shamanist traditions mean that Siberians have been brought up with strong non-violent or “ethics of balance” beliefs concerning killing of humans or hunting of non-human persons. It is extremely difficult for many Siberians to condone Russia’s violent aggression and continued war in Ukraine since it runs against their non-violent understanding of best-practice human relationships and human interactions within the natural world. The Ukraine war is painfully against the Indigenous values that many consider their true heritage, and I therefore do not trust public opinion data from the republics that indicate a majority are pro-Putin and pro-war. Protests in the form of public prayers have occurred in Buryatia and Altai.

For some Sakha, especially a group of women activists, pacifist values were expressed in a 2022 protest demonstration in the main square of their capital, Yakutsk, expressed quite dramatically in the form of a chant-dance called okhuokhai. This powerful expression of creative politics was traditionally used to chant improvisational poetry in honor of the summer solstice, often in the contexts of major ceremonial meetings of numerous Sakha clans, including for meetings of negotiation and agreement concerning inter-tribal relations. It resulted not only in a protest that was viewed on non-official social media all over the world, but also in a serious crackdown and arrest of nearly all the protesters.[12]

Conclusions

Despite the high costs, I believe the courageous Siberian protests that have resonated especially with the non-Russian communities and republics in all of Russia, have significance as models exemplifying hopes for a better, less racist and more democratic society. Whether ultimately, Indigenous communities choose secession, despites threats of crack-downs and civil war, will depend on them and the urgent need for their traditions of calm negotiation and consensus building to be re-activated. This requires brave leadership, especially including women. In the last two years, a fascinating set of creative protests using traditional cultural idioms — Buddhist prayer, okhuohai, camel sacrifice – has meant that Indigenous leaders sometimes signal one message to insiders (the need to stop the Ukraine war and bring sons home) and another to outsiders in Moscow (we are patriotic and support our fighting sons).

Research and policy decisions must be driven by Indigenous leadership. For non-Native “ally” researchers, personal values, compatible worldviews, rapport, and similar research goals are interactive, growing during collaboration. Environmental activism based on principles of ecological interconnectedness (ecosophy) has become particularly perilous, as have anti-war stances. Open-minded, equality- based partnership between Western and Indigenous scholars could allow deeper thinking about interactive processes of peacebuilding policies.

[1] RAIPON was founded in the late Soviet period but suspended and then coopted in 2011 (cf. Balzer 2016).

[2] The NSF projects were guided first by Noel Broadbent, and then anthropologist of Chukotka Anna Kerttula. An example is Vera Solovyeva (2021), present here. Issues of land, development, and rights also featured in the early 21st century programme of the Scott Polar Research Institute (University of Cambridge) and the Northeast University of Sakha Republic, led by Piers Vitebsky and Florian Stammler. This programme has resulted in numerous excellent coauthored publications. An example is Habeck and Belolyubskaya (2016). See https://www.s-vfu.ru/en/projects&activities/joint_research/ (accessed 14 September 2022).

[3] See especially Gertjan Plets, Nikita Konstantinov, Vasilii Soenov, and Erick Robinson (2013), a collaborative European-Altaian project; and Tadina (2020). For perspective on “Indigenous methodology”, see Vinokurova 2018b, c).

[4] Uliana A. Vinokurova is Director of the Circumpolar Civilization Research Center at the Arctic State Institute of Culture and Arts in Yakutsk. Among her many publications, see Vinokurova (1992; 1994; 2011; 2018a, b, c); Vinokurova, Shilin & Lapina (1995). She published in Marjorie’s journal, influencing themes and introductions, in 1995, 2008, and 2014. For more on our interactions, see Balzer (2011, 2021).

[5] Among the accusers was Director of the Institute of Ethnography and Anthropology (later of Ethnology), Valery Tishkov, leader of the Academy of Sciences and UNESCO project ‘Ethnicity, Conflict, and Agreement’ that produced significant volumes on many of the republics in the 1990s and was successor to the 1980s’ Social Science Research Council project on ‘Ethnic Processes’ founded by Yuliian Bromlei.

[6] The Prague conference, held in a palace donated by Václav Havel, was the first of several where the coauthors were able to participate as collaborators. The late Leokadiia Drobizheva, then in the Institute of Ethnography and Anthropology of Russia’s Academy of Sciences, was known for saying that ethnic polarization begins at the centre, with Moscow policies, rather than in the republics. A mentor of Uliana’s, she trained many prominent sociologists of the republics, especially after she became Director of the Institute of Sociology. U.S. leaders of the MacArthur and IREX-funded project included Women in International Security (WIIS) founder Catherine Kelleher, who later helped Uliana fulfil a dream of taking Native Siberian women leaders on a tour of the United States and Canada to meet Native American women leaders. It resulted in Uliana’s monograph in the Sakha language about First Nation education and self-rule (Vinokurova and Tret’iakova 1999).

[7] Sadly, 1992 Sakha Constitution was later revised to correlate with the 1993 Russian Federation Constitution.

[8] See https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/09/23/russia-partial-military-mobilization-ethnic-minorities/, last visited March 18, 2024.

[9] Available at: https://www.reddit.com/r/UkrainianConflict/comments/11cf11i/new_map_of_dead_soldiers_per_capita_in_russias/, last visited March 18, 2024.

[10] baikal-journal.ru/2023/06/20/u-muzhchiny-iz-buryatii-veroyatnost-umeret-na-vojne-primerno-v-75-raz-vyshe-chem-u-moskvicha/), in part using BBC data from demographic-research.org/volumes/vol48/31/48-31.pdf , last visited March 19, 2024.

[11] See https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/R/bo16552160.html, last visited on March 18,2024.

[12] See Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer https://russiapost.info/regions/polarization, last visited April 9, 2024; https://novayagazeta.eu/articles/2022/09/25/women-protest-against-mobilisation-in-yakutia-police-break-up-protest-authorities-claim-it-was-held-in-support-of-mobilised-men-news including a video clip of arrests.

Yulia Navalnaya’s Decolonization Critique Proves That Russia’s Liberal Opposition Hasn’t Been Listening to Indigenous Voices

At the Bled Strategic Forum in Slovenia, Yulia Navalnaya, widow of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, delivered a speech emphasizing the need for a unified European strategy towards Russia. While much of her address echoed previous calls to support Russian civil society and democracy, one particular segment sparked controversy among Russian-speaking social media users.

Navalnaya remarked: “Some advocate for the immediate ‘decolonization’ of Russia, suggesting that breaking up our vast country into smaller, supposedly safer states is the solution. However, these ‘decolonizers’ fail to explain why people with shared cultural and historical roots should be separated, nor do they offer a clear path for how such a process would unfold.”

After her speech was translated into Russian and shared on social media by Team Navalny, it was met with criticism from ethnic and decolonial activists. Many were offended, pointing out that advocates for decolonization have long explained the concept, emphasizing self-determination and its relevance to Russia’s future.

The backlash highlights a persistent issue: Team Navalny, a major opposition group, appears reluctant to engage with the perspectives of Russia’s Indigenous populations, whose views on the country’s colonial past and present are often at odds with the mainstream opposition narrative.

Indigenous communities found Navalnaya’s comments particularly hurtful, viewing them as an echo of Kremlin propaganda that portrays decolonization efforts as dangerous separatism. They also criticized her failure to acknowledge the ongoing repression of ethnic and Indigenous activists by the Russian state. The tone of the Russian translation of her speech, whether intentional or not, was perceived by some as threatening.

Many on social media voiced disappointment and anger, with several Indigenous activists reaffirming their right to self-determination, independent of Moscow’s influence.

It’s important to recognize that Navalnaya’s speeches likely reflect the collective position of Team Navalny and the Anti-Corruption Foundation, rather than her personal opinions. The anti-decolonization rhetoric is aimed at courting certain Western liberal politicians and right-leaning audiences, who often harbor anti-Indigenous views.

This message also aligns with the Russian liberal opposition, largely made up of middle-class urbanites from Moscow and St. Petersburg, who tend to overlook the historical exploitation of Russia’s regions and ethnic republics, which have contributed to the prosperity of central Russia.

From the perspective of Indigenous activists, the push for Russia’s “Europeanization” seems misplaced, especially given that a significant portion of the country lies in the Caucasus and Asia, home to diverse peoples with unique cultures and histories of colonization.

This controversy underscores the deep divide between Moscow-based liberals and Russia’s Indigenous communities. As a result, many Indigenous groups are likely to continue charting their own course for the future, independent of the mainstream opposition movement.

The situation reveals the complex intersection of politics, ethnicity, and historical grievances within Russia’s opposition, and the challenges of crafting a unified vision for the country that addresses the concerns of all its diverse populations.

“We are nobody here…” A report from Yugra, where oil workers are displacing the Khanty from their ancestral lands

In the summer of 2024, human rights advocates from the “Public Radar” project appealed to Russian authorities with a proposal to amend legislation allowing industrial companies to exploit lands traditionally used by Indigenous peoples. This initiative stemmed from complaints by residents of the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug – Yugra, where oil companies have been building infrastructure on ancestral lands for decades without the owners’ consent.

These ancestral lands, legally known as territories of traditional nature use, are granted to Indigenous peoples for activities like reindeer herding, fishing, and gathering berries and mushrooms. However, these communities do not have ownership rights over the land.

Oil companies, by contrast, operate with few restrictions. Although regional laws require them to coordinate with Indigenous representatives before establishing infrastructure, refusal is not an option. The federal agency Rosnedra issues oil extraction licenses without considering the Indigenous stance. Therefore, negotiations often focus on compensation rather than consent.

If any Indigenous community members refuse compensation and simply ask that no oil extraction occur on their land, the drilling proceeds regardless. The dissenters are told to file complaints, where the legal machinery of the oil corporations works against them.

As a result, many Indigenous communities have resigned themselves to the situation. The bravest only fight for fair compensation, as the oil infrastructure not only occupies their land but often malfunctions, leading to oil spills. In places where oil contaminates the soil, reindeer cannot graze, and berries won’t grow.

A correspondent from “Kedr” visited the ancestral lands in the Surgut district of Yugra to document how corporations are displacing Indigenous peoples from their territories.

This article discusses the current struggles of the Indigenous peoples of Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug: what they are fighting for and their current demands.

We previously covered how the Khanty fought to protect their lands and way of life in past years, even pushing for a referendum to ban the expansion of oil drilling, only to be suppressed by the authorities, in our report “Oil – The Provider”.

Forbidden Territory

“You need to warn me to stop; I might forget and drive you straight to the checkpoint, and no one will get through. Russians aren’t allowed at the camps unless they’re oil workers,” said Anatoly Vandymov, a Khanty man, driving an old car through the taiga. We were headed 150 km from the village of Nizhnesortymsky to Anatoly’s ancestral lands, where he lives with his family and where his two dozen reindeer graze.

Our party included Vandymov, me, and a guide named Oksana, with whom I would navigate the forbidden area. In the 2000s, the company Surgutneftegaz set up checkpoints and began restricting non-Indigenous residents from accessing oilfields and ancestral lands. Initially, this was done at the request of the Khanty themselves, who were frustrated by outsiders hunting and fishing. But over time, these restrictions turned against the Indigenous people: now, the Khanty need Surgutneftegaz’s permission even to visit neighboring ancestral lands where oil is being extracted.

The journey from Nizhnesortymsky to the camp takes about two hours, a trip Vandymov makes several times a week to buy supplies. Anatoly, aged 40, is short and, like many Indigenous people, looks younger than his years. At home, his four children and wife wait for him, while his eldest son has already grown up and found a bride.

Vandymov, like nearly everyone here, works for Surgutneftegaz as an inspector, checking for pipeline ruptures. According to Anatoly, locals are rarely promoted to higher positions within the company, and there’s no other work in Nizhnesortymsky that allows them to maintain their traditional lifestyle. Anatoly adds with a grin that he took the job at Surgutneftegaz to keep an eye on the oil workers and what they do on his land.

In his spare time between shifts—two weeks on, two weeks off—Vandymov fishes, tends to his reindeer, and hunts.

To enter Khanty ancestral lands, we had to pass through the oil company’s checkpoint, located halfway between the village and Vandymov’s lands.

“The guards at the checkpoint are often rude to locals. There was an incident with my younger brother; they wouldn’t let him onto our lands because he was traveling with another Indigenous man whose lands are elsewhere. When my brother asked to see their documents, they told him he ‘wasn’t grown enough to ask for documents’—he’s 22! When he threatened to report their behavior, one of the guards said that if nothing happened after the complaint, he’d beat my brother up. How can they act like this? Whenever we complain or speak to the media, security becomes stricter, and the guards’ rudeness increases,” says Anatoly.

Eventually, the security staff received a disciplinary talk, according to the company. Surgutneftegaz responded to Anatoly’s complaint by saying, “We conducted a preventative conversation with the security guards regarding inappropriate behavior towards citizens.”

Non-Indigenous people who do not work in the oil industry are not allowed past the checkpoint—even to visit Khanty friends. The Khanty believe Surgutneftegaz fears environmentalists or journalists might infiltrate oil extraction zones. Indigenous people from other areas cannot pass the checkpoint without permission from the company’s Indigenous Affairs engineer.

The car stops a couple of kilometres before the security checkpoint. From here, Oksana and I continue on foot through the burned forest, where a fire swept through last year. Our feet sink into the deep moss.

Suddenly, a reindeer appears among the blackened trees. It has strayed from its herd and looks around nervously. Oksana tells me we must catch up and photograph it to find its owner, but the reindeer allows only a distant snapshot before fleeing at the slightest movement.

Reindeer are not just livestock for the Khanty. Their hides are used for clothing, and they pull sleds through deep snow into the taiga.

“Reindeer can live without humans, finding their food, like lichen. But they must be supplemented with grain or fish, and in summer, smoke is used to drive away mosquitoes,” says my guide.

We eventually reach the road where Anatoly is waiting. The drive continues for another hour and a half. This industrial road was built by Surgutneftegaz, and the oil workers often remind locals that they benefit from it, though it wasn’t built for the herders but to transport employees and oil. There are about a hundred exploration wells, cluster pads, oil and gas extraction workshops, pipelines, and gas turbine power stations on Vandymov’s ancestral lands.

Anatoly’s family has held these lands for three generations. He and his wife, mother, and brother’s family tend a herd of twenty reindeer. However, herding is becoming increasingly difficult due to expanding oil extraction.

“We have few reindeer, but it’s hard to manage them because of the roads where they are often hit by cars, and the pollution. We’re forced to move farther away, but we have less and less land.”

The oil workers bury domestic waste and spilled oil products near the well pads. During accidents, oil leaks are supposed to be cleaned up and removed, but the companies cut costs. When there’s a spill, they scrape off the top layer of soil and bury it nearby, contaminating the groundwater, explains Anatoly.

The source: https://kedr.media/stories/my-zdes-nikto/

Just Transition Indigenous Summit will be held on October 8-10 in Geneva

The Just Transition Indigenous Summit aims to address the impacts of the energy transition on Indigenous communities and prioritize their perspectives and solutions. Scheduled for October 8-10, 2024, in Geneva, this summit will convene over 100 representatives from Indigenous groups across the globe.

As governments and corporations pivot towards a low-carbon economy to address the climate crisis, there is often a neglect of the rights of Indigenous Peoples as defined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). These rights include the principles of self-determination and Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC). The summit intends to challenge conventional narratives regarding the Just Transition and underscore the necessity of integrating Indigenous values and rights into all phases of project development and implementation.

The objective of the summit is to affirm a rights-based approach relevant to any extractive projects proposed on Indigenous lands. It will establish criteria and safeguards that align with the principles of Just Transition. Discussions will focus on ensuring that projects do not replicate the harms associated with fossil fuel extraction and other traditional resource developments.

This summit represents a significant gathering where Indigenous Peoples from seven socio-cultural regions will unite to collectively redefine the Just Transition and the notion of a “Green Economy” from their distinct perspectives.

Rodion Sulyandziga, Chair of the Indigenous Peoples Global Coordinating Committee, emphasizes the importance of Indigenous-led initiatives within the broader context of environmental policy and resource management, underscoring the commitment to the protection and upliftment of Indigenous voices in the transition to a sustainable future.

The Just Transition Indigenous Summit serves as a pivotal platform for advocating the rights of Indigenous Peoples, driving forward their priorities and contributions in the ongoing movement towards a more equitable and sustainable global economy.

Russia’s Control Over Sami People

The situation regarding the Indigenous Sami people in Russia is grave, as they are being compelled to conceal their identity due to government pressures and legal changes. The Russian administration’s actions threaten their cultural heritage and autonomy, outlining a broader narrative of dominance over minority groups.

The Russian government is implementing measures that compel Indigenous Sami people to suppress their identity. This initiative is likened to an attempt for “total control” over these communities, undermining their cultural expressions and traditions. The Ministry of Justice has introduced 55 new Indigenous groups, further complicating the representation of Sami identity within legal frameworks.

Cultural Erosion

The enforced assimilation policies pose a significant threat to the Sami’s traditional way of life. As legal pressures mount, many Sami individuals experience a disconnection from their cultural roots, leading to a gradual erosion of their identity. This tactic is detrimental not only to the Sami themselves but also to the richness of cultural diversity that exists within Russia.

Historical Context

Historically, Indigenous communities, including the Sami, have faced marginalization and systemic oppression. The current situation marks a continuation of such practices, reflecting a persistent struggle against the dominant narratives imposed by state authorities. It is crucial to recognize the historical context behind these contemporary issues to understand the depth of the conflict.

International Response

The global community has begun to take notice of the plight of Indigenous peoples in Russia, with calls for intervention and support. Activists and human rights organizations are urging for a unified response to safeguard the rights of the Sami and other Indigenous groups. Addressing these urgent concerns is essential in preserving the cultural integrity and livelihoods of marginalized communities.

Advocacy for Indigenous rights appears essential in combating these repressive measures. By raising awareness and pushing for policy changes, there is hope for the Sami people to reclaim their identity and cultural heritage. Continuous international support and solidarity are necessary in the pursuit of justice and recognition for Indigenous rights.

Taken from here

Joint Side Event of Arctida and ADC Memorial Brussels at the OSCE Human Rights Conference: Criminalization and Destruction of Indigenous Peoples in Russia: State and Corporate Violations

Date: October 8, 2024

Time: 13:30-14:30

Location: Hotel Sofitel Victoria, Warsaw, Opera Room

This event will focus on the severe challenges facing Indigenous peoples in the Arctic zone of Russia, including state repression and environmental devastation by mining companies.

The discussion will be led by Ilya Shumanov, head of the NGO Arctida, alongside independent experts from the Indigenous peoples’ movement. Shumanov will present recent findings from his team, revealing how GONGOs (government-organized NGOs) funded by mining companies like Nornickel, in collaboration with corrupt Indigenous representatives, are lobbying for the removal of international sanctions on these corporations.

Independent experts will provide insights into the real situation on the ground, where traditional lifestyles in the Tundra and Taiga are under threat. Mining operations are destroying the environment, polluting water and air, and making it impossible for Indigenous peoples to continue their traditional practices of hunting, fishing, and gathering. Despite the vast wealth generated by these companies in the Arctic, none of it reaches the Indigenous communities. Those who speak out against this exploitation and destruction are criminalized and branded as extremists by the Russian state.

Taken from here

Pavel Sulyandziga, Dmitry Berezhkov “We Have Learned to Understand You to Defend Ourselves: The Dialectics of Yulia Navalnaya’s Slovenian Theses”

September 10, 2024

“The price of greatness is responsibility,” said British Prime Minister Winston Churchill during his visit to Harvard University in 1943. This phrase remains a treasure of global political thought, defining the boundaries of what is acceptable for public figures and simultaneously creating a collision between what is desired and what is possible. Recently, Yulia Navalnaya, the widow of the well-known Russian opposition politician Alexei Navalny, found herself in such a collision at a political forum in Slovenia.

After her husband’s assassination, Yulia Navalnaya became a symbol of resistance to Putin’s regime for many and turned into one of the most vocal representatives of the “Russian opposition.” It should be noted that the term “Russian opposition” is not particularly apt. It doesn’t carry significant meaning in the current conditions and may rather denote participants of “political emigration” rather than a real political opposition. However, it must be acknowledged that “political emigration” can, under favourable conditions, quickly become a political opposition or even gain real power (we all remember the history of the “sealed train”) in a given country.

At the strategic forum in Bled, Yulia Navalnaya delivered a speech on the need for Europe to stop making tactical decisions regarding Russia and instead develop a long-term strategy. Her impeccable political fundraising performance sparked extensive discussions within the “ethnic emigration” community, a term used to describe political activists and human rights defenders representing indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities of Russia who have found themselves in forced emigration.

With all due respect to Alexei Navalny, a brave and consistent political opponent of Putin, it should be recognized that many Ukrainians remember him for his phrase “Crimea is not a sandwich.” No subsequent actions or sacrifices could change this perception.

As a result of the Slovenian forum, Yulia Navalnaya risks being remembered by Russia’s non-Russian nations as someone who threatens (presumably after coming to power) to seek out those who are planning to “decolonize” Russia.

We will return to the form of Navalnaya’s speech, but the mere fact that the term “decolonization” was placed in quotation marks in the text of her political declaration indicates a desire to diminish its significance and present it as an artificial phenomenon, essentially making it appear insignificant.

However, decolonization is a much broader concept than just dividing large countries into smaller ones (as suggested by Yulia Navalnaya). Political practices of recent decades have demonstrated this. There are numerous interpretations of decolonization: decolonization of legislation, culture, art, science, cinema, and more.

Moreover, decolonization is becoming a dominant phenomenon in modern politics. How else can Putin’s war against Ukraine be described if not as “colonial”? And how else can Ukrainian resistance to the Russian army be described if not as anti-colonial? The empire wants to reclaim what it sees as its “own,” while the former colony resists.

Yulia Navalnaya, in her speech, condemns decolonization, equating it with simply dividing a large country into smaller and safer states: “It is supposedly necessary to divide our too-large country into a couple dozen small and safe states.”

But if we recall the classic definition of decolonization as the process by which European colonies gained political independence after World War II, we can assume that for some inhabitants of the vast British Empire (primarily the white population of the metropolis), its collapse was a tragedy, dividing a large country into dozens of smaller ones. However, for dozens of nations around the world, this process was an opportunity to gain independence, human dignity, and their national “self.” They likely didn’t care what British propaganda thought of them, as their goal was the chance to gain freedom and independence from the empire.

It is worth noting that deliberately diminishing or belittling a public phenomenon and its associated terminology is a special approach often used by representatives of the ruling class (though we hesitate to use Marxist terms, they fit well in this context) to counteract that phenomenon. This approach has been used in history before—recall Lenin’s famous phrase about “the intelligentsia, lackeys of capital who consider themselves the brain of the nation…”

For a public figure using such an approach, it is important to highlight their “correct” view of a phenomenon while simultaneously casting shadows or discrediting other interpretations. Following this logic, Vladimir Putin, discussing the collapse of the USSR, referred to it as “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century,” without mentioning that thanks to this “catastrophe,” millions of residents in places like the Baltic states gained the opportunity to live in free and economically developed democracies.

In her statement about decolonizing Russia, Yulia Navalnaya almost word for word (excluding the specific jargon of a former KGB officer) reproduces Vladimir Putin’s hate-filled speeches against Ukraine and the West: “After the collapse of the USSR, our geopolitical adversaries undoubtedly set themselves the goal of further dismantling what remains of historical Russia, that is, collapsing its core, Russia itself—the Russian Federation—and subordinating everything that remains to their geopolitical interests. I speak confidently about this as a former director of the FSB…”

On this issue, Yulia Navalnaya willingly or unwillingly adopts the stance of a typical representative of the ruling class and retransmits Putin’s message about dividing the majority, without mentioning the possibility of gaining freedom for minorities.

The authors of this article understand the wave of outrage that Navalnaya’s speech provoked among ethnic activists and representatives of Russia’s indigenous nations, who assert that in the issue of self-determination of nations, “Putinists” and “Navalnyists” are the same; that it doesn’t matter who is in power in the Kremlin; that, in any case, its master automatically becomes a representative of imperial interests.

We remember the communists, who used an iron fist to suppress the aspirations for self-determination of the nations within the USSR while supporting it around the world, primarily in the territories of Western empires. Then came the Democrats led by Yeltsin. Those they couldn’t physically hold (the Union republics) were released. Where there was strength, they clung tightly (the two Chechen wars). Then came the Putinists, who began to extol the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe,” and then turned to the familiar military actions in Georgia, Crimea, Donbas, and the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

And if Navalnaya were to come to power, would she do the same thing under the guise of democracy? How would Yulia Navalnaya handle Chechnya, for instance, where almost no Russian population remains and which, according to the democratic standards of the “Beautiful Russia of the Future” (BRF), might seek independence? Would she negotiate? Allow a referendum? Or would she argue that “we cannot divide our too-large country into a few dozen small and safe states” and send in the troops?

And if the Kremlin under Navalnaya’s leadership agrees to grant independence to Chechnya, and then Tuva, where the Russian population is about 10 per cent, asks for independence? Will there be differences in approach? If so, why? And how is Tuva different from Sakha (Yakutia)? And so on.

We don’t want to delve into long discussions, but it’s worth mentioning the passage about people with a “shared background and cultural context” in Yulia Navalnaya’s speech. In our view, the inhabitants of the USSR had a shared background, as do the current residents of Russia, as did those in Yugoslavia. Other examples can be recalled. We see right now how this “background” works by examining the reaction of Russians to the occupation of part of Kursk Oblast by Ukraine. Did they rush to defend Kursk Oblast, not giving up an “inch of Russian land,” or did they continue to visit theaters in Moscow and watch evening shows? That is the nature of this common background. On the surface, it exists, but in reality, it is not very common. The language is common—so is it with New Zealand and Great Britain.

The authors find it pointless to discuss this passage at length because we have closely followed the discussion that unfolded online after Yulia Navalnaya’s speech. We’ll just quote a few comments that give an idea of how “background” is perceived:

“Yulia, our shared background as Caucasians with you is such that you are historically occupiers. And our shared cultural context is absent; we have simply learned to understand you to protect ourselves, but you know absolutely nothing about us.”

“Then why should people with different backgrounds and cultural contexts live in one country?! You have more in common culturally with Ukrainians than with Chechens, yet Ukrainians do not want to live in the same country with you, while Chechens are supposed to?”

It would also be interesting to know how many volunteers Vladimir Putin would have recruited for the war with Ukraine if he didn’t pay enormous sums by Russian provincial standards or recruit people from prisons. How many volunteers would go to war in the name of “shared background”? And does Yulia understand how quickly the so-called “shared background” can become non-shared after another session in Belovezhskaya Pushcha?

For us, the most important aspect of such discussions is DIALOGUE—the ability to speak with both the strong and the weak, the “great” (to recall Churchill’s words) and the downtrodden and the impoverished.

But dialogue cannot be a monologue. Yulia Navalnaya’s speech at the forum in Slovenia can only be described as a monologue from a representative of the white, dominant majority. We would like to clarify that this characterization might seem tactless in the Russian context, but in international practice, and especially within decolonization discourse, such terms are not unusual.

In our view, this is the key reason for the outrage from representatives of ethnic minorities and indigenous nations (decolonization activists, if you will) regarding the discussions about the future by representatives of the current political emigration—advocates of the “Beautiful Russia of the Future.”

Their future—the future of decolonization activists, their relatives, and their nations—is being discussed without their participation, and they are being told how they will live. Isn’t this an imperial approach? In a similar vein, Vladimir Putin dictates how Ukraine should live within the framework of the “Beautiful Russia of Today,” but Ukraine, for some reason, has no desire for this.

For the indigenous, numerically small nations of the North, Siberia, and the Far East (as we have written about repeatedly), who live traditional lifestyles, the size of the country, the structure of governance, or the person in power are less important than the principle of the state’s commitment to democracy, human rights, and the rights of nations to self-determination. This principle can be successfully implemented both within a united state like the Beautiful Russia of the Future and within separate national entities.

For us, democracy, freedoms, and rights are primary—not the form of government or the name of the person in power. We hope there is no contradiction in this regard between us and the advocates of the “Beautiful Russia of the Future,” as well as with the representatives of the “League of Free Nations,” who propose dismantling the Russian Federation and creating independent national states in its place.

Continuing the discussion of Yulia Navalnaya’s thesis on decolonization, we recall an interview with the well-known representative of Russian “political emigration,” Gennady Gudkov, who also criticizes this term, stating that its inclusion in the PACE Resolution plays into Putin’s propaganda. In this context, we believe:

Putin’s propaganda does not care what Gennady Gudkov or ethnic activists say. Propaganda can turn anything into gold or trash, and vice versa. It doesn’t matter what material is fed into the furnace as fuel.

The influence of Gennady Gudkov, as well as Yulia Navalnaya and the overall “Russian opposition,” on the situation within Russia today is so minimal (we must unfortunately acknowledge this) that it is practically indistinguishable from the influence of ethnic activists demanding self-determination for their nations (which we must also regretfully acknowledge). These voices currently have little impact on the internal situation in Russia and are successfully used by Russian propaganda in the “holy war” against the West.

Thus, in our view, this discussion represents a pure competition of ideas—Gennady Gudkov and Yulia Navalnaya’s vision of the “Beautiful Russia of the Future” on one side and ethnic activists’ idea of “dismantling the empire” on the other. The dominance of Gudkov and Navalnaya’s position in the West is merely evidence that there are more Russians and fewer non-Russians, that Russian intellectual, financial, and administrative potential exceeds the “ethnic” potential. This is the case both within Russia and in emigration.

In general, this discussion is a replication of the decolonization discourse. If we draw a historical parallel, we can say that the Siberian nations, conquered by the Cossacks in the 16th–18th centuries, also had their own perspective on the events, but it was crushed by the viewpoint of the Cossacks, who represented the empire. Primarily because there were more Cossacks (literalists will quickly refute this thesis, but we mean that the empire could send endless waves of conquerors, while the conquered nations, quickly exterminated by firearms and diseases, were a finite group), the Cossacks were better educated, and their weapons surpassed those of the natives. Thus, in the case of Navalnaya and her Slovenian speech, we see a mere repetition of history.

In this article, we would also like to comment on the form of presentation of Yulia Navalnaya’s speech, prepared by her team. We observe that the main discussion following the speech focused on the substance—whether Russia is an empire and how it should be decolonized. However, few have paid attention to the presentation of the material, which we find equally important.

It should be noted that Navalnaya’s key thesis on decolonization, which triggered a fierce reaction from decolonization activists, was presented in slide No. 7 of the Russian-language version of her Instagram publication. The passage on decolonization was visualized there using a technique that, in the Russian context (without additional explanation), can be interpreted as threatening: “Finally, we will find those who talk about the need to urgently ‘decolonize’ Russia. Supposedly, we need to divide our too-large country into a few dozen small and safe states. However, ‘decolonizers’ cannot explain why people with a shared background and cultural context should be artificially divided. Nor do they specify how this should happen.”

Perhaps this slide, with its “threat,” was made by accident? Maybe. Or maybe it was made out of foolishness? That’s also possible. The subsequent explanations that this slide was taken out of context do not seem reasonable to us. Such a reaction could have been anticipated; it is obvious, especially when it comes to such a sensitive issue as national self-awareness.

Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that this visualization of the thesis about decolonizers was intentional. But why?

The use of such a negative visual technique seemed strangely familiar to us, evoking a sense of déjà vu. It reminded us of another work by “Navalny’s Team”—the famous film *Traitors* about the 1990s. The film addresses the establishment of democracy in Russia and the rise of dictator Vladimir Putin.

Following the release of this film, a significant discussion began on the Russian-speaking internet. Many felt (and justifiably so) that the film’s creator, Maria Pevchikh—one of the ideologists of the modern “For Navalny” movement—besides recounting the 1990s, personally attacked Mikhail Khodorkovsky.

Many asked: “Why wage war against Khodorkovsky now, when it is more important to unite around the idea of opposing Putin?” From a political perspective, especially from the perspective of a politician thinking about power in future Russia, this action—attempting to “destroy” Khodorkovsky, who could have been a potential ally—seems unreasonable (at least at this stage).

The authors of this article reviewed all three episodes of the film again. Maria Pevchikh repeatedly shows photos of Khodorkovsky when she talks about “traitors” and “oligarchs who sold out democracy.” Historically accurate, perhaps—but one episode about Khodorkovsky and the “loans-for-shares” auctions would have sufficed. Instead, Pevchikh repeatedly nails Khodorkovsky to the pillory of oligarchy.

From a strategic point of view, the film *Traitors* is a mistake. It turns potential allies into enemies, weakening the ability to oppose Putin’s regime. It does not unite but divides. Numerous commentators of the film rightfully criticized Pevchikh, saying she did not delve into the topic, did not understand the facts, and presented only one side, essentially turning the film into a propaganda piece.

Critics argued that while the film is valuable for opening a discussion about the 1990s—a period that has not yet been fully reflected upon in Russian consciousness—it was poorly timed, causing discord among potential allies. Reasonable politicians do not act this way (once again, Churchill comes to mind, who made a “deal with the devil” to achieve victory).

However, we believe that the film *Traitors* should not be assessed from a political strategy perspective at all. The film, in our view, does not carry political weight. If we look at the actions of Pevchikh’s team from a different angle—focusing on political fundraising and the possibility of eliminating a competitor—then her film becomes a meaningful and reasonable action. Pevchikh’s team is strategically targeting several goals: creating a watchable product, presenting their version of the 1990s and Putin’s rise to power to the younger generation, thereby “fighting the regime,” while simultaneously tarnishing a competitor.

Some may ask—what does fundraising have to do with it, and what does Khodorkovsky, who is quite wealthy himself, have to do with it? However, political fundraising is not just about money. It is also about the ability to connect with decision-makers, to sell your ideas to politicians—in our case, Western ones.

Additionally, with the help of our colleague Anna Gomboeva, we noticed a difference between the Russian and English versions of Yulia Navalnaya’s Instagram publication. The passage on decolonization is absent from the English version. Anna suggested that Navalnaya’s team, considering the West’s attitudes toward decolonization issues (such as Black Lives Matter), excluded this paragraph from the English version to avoid incurring the wrath of Western human rights activists.

In the English version of the speech, there is no mention of Navalnaya’s team planning to find decolonizers after coming to power: “Finally, there are those who advocate for the urgent ‘decolonization’ of Russia, arguing to split our vast country into several smaller, safer states. However, these ‘decolonizers’ cannot explain why people with shared backgrounds and cultures should be artificially divided. Nor do they say how this process should even take place.”

This technique and form of presentation raise many questions and create a sense of ambiguity and double standards. It turns out that one message (conflictual) is sent to the Russian-speaking audience, while another is sent to Western partners.

One might assume that Slide No. 7 in the Russian Instagram was intentionally made to provoke a storm of angry emotions. In our view, this was a deliberate provocation.

We are already seeing emotional statements from some ethnic activists online comparing the Russian people to fascists, calling to stop “kissing Russians in…” or even calling to “flatten Muscovy to the ground.”

These emotions can certainly be used in future rounds of political fundraising, presenting Western politicians with a narrative like: “Look at these decolonizers—they are a horde of militant chauvinists. They are furious now, but give them power, and they will drive out (or slaughter) all Russians from their republics.”

From the perspective of a politician building a strategy for actually coming to power in a multinational country, publishing Slide No. 7 is short-sighted and erroneous. From the perspective of political fundraising, however, it is perfect—a well-timed attack on competitors in the fight for Western attention, remaining obscure to the Western audience, who will only see the English text and not delve into the nuances of the Russian version.

Nevertheless, we must acknowledge that Yulia Navalnaya, in her speech, raised a key question—a “research question,” if you will: How, after all, should this decolonization process unfold?

It should be noted that the term “decolonization” has recently been battered from various sides, and some are beginning to distance themselves from it. This is facilitated by both Yulia Navalnaya’s Slovenian speech and similar speeches by political émigrés, as well as, unfortunately, by the statements of certain decolonization activists. Both sides often reduce the understanding of decolonization to simply “dividing the large into the small.”

Meanwhile, as we have already mentioned, decolonization is a broad concept. For the indigenous peoples of Siberia and the Arctic in Russia, the primary concern is the ability to maintain their traditional way of life—to hunt, fish, and herd reindeer freely on their ancestral lands, and to preserve their customs, culture, languages, and traditions.

For us, the concept of decolonization, the mirror image of which is the concept of national self-determination, means the ability of Indigenous communities to make decisions about seemingly simple but vital matters—where to fish, when to gather, and how to hunt. And if not by themselves (we are not retrogrades and understand that indigenous peoples do not live in isolation), we would like decisions to be made with consideration of these communities’ opinions, so that, for instance, a coal mine doesn’t suddenly appear where there used to be pristine forest, extracting billions for unscrupulous businessmen.

In international law (the only real structure that protects the rights of Indigenous and small nations), tools such as co-management mechanisms and the principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) have long been developed. It seems that to fully explain our position on this issue, another article (or more than one) would be needed.

However, we understand that other members of the public may imbue the concept of decolonization and national self-determination with different meanings, including the creation of separate ethnic states. And this is normal. It is a natural desire to gain autonomy in deciding one’s fate. For the Indigenous, numerically small peoples of Siberia and the Arctic, such a solution is likely impossible due to their small numbers. But for other, more numerous nations, the desire for such a solution does not seem unnatural to us.

That being said, we believe some representatives of ethnic emigration are disingenuous when they claim not to understand why many in the West fear the creation of independent, democratic national states on the map of present-day Russia. It seems unlikely that any Western politician fears the formation of three dozen independent, prosperous, and democratic Estonias on Russia’s territory.

What they fear is not this. They fear violence, having been taught bitter lessons by the experiences of Yugoslavia, the Middle East, and other regions. They fear even greater bloodshed (given the presence of nuclear weapons) than what we are witnessing today.

In our view, this anxiety is at least understandable, and certain representatives of Russian political emigration use it for their political fundraising purposes.

Paradoxically, we believe that simply mentioning decolonization by a public figure as prominent as Yulia Navalnaya is already a positive sign. For us, it means that the community of people who consider their homeland and national interests to be located within present-day Russia is beginning to ask the right questions.

The authors of this article do not have ready answers to these questions. We see decolonization and self-determination as processes rather than endpoints.

However, we will have to search for these answers together, whether you are thinking about the Beautiful Russia of the Future or striving to bring freedom to your nations.

However, one thing is certain: the first step in this direction must be dialogue and mutual renunciation of violence and insults. A dialogue that truly seeks to understand each other. As one literary character once said, “You never really understand a person until you consider things from their point of view until you climb inside of their skin and walk around in it.”

We are also convinced that only the victory of the Ukrainian people in this war for their freedom can help the peoples of Russia achieve theirs as well.

The tragic fate of Albert Razin, a fighter for the Udmurt language

5 years ago, on September 10, 2019, Albert Razin, a 79-year-old Udmurt scientist and public figure, committed “tipshar’, an act of self-immolation near the building of the State Council of Udmurtia in Izhevsk. Banners were found next to him, in which he demanded to save the Udmurt people and language.

“Tipshar” is a form of extreme protest among the Chuvash and Udmurts to preserve honour and dignity in a situation that cannot be fixed.

This tragic event shocked not only Udmurtia but also all of Russia, drawing attention to the problems of preserving the national languages and cultures of small peoples.

Albert Alekseevich Razin was a candidate of philosophical sciences and an honoured scientist of the Udmurt Republic. Throughout his life, He actively fought for the revival of the Udmurt language and national customs. Razin stood at the origins of many national Udmurt organizations created after the collapse of the USSR, including the “Udmurt Kenesh” (Udmurt Council). He tried to stop the linguocide of the Udmurts by Moscow. It was not suicide, but a conscious act aimed at preserving national identity.

The scholar called himself a “peasant scholar” and a “Tolstoyan”, believing that the preservation of the Udmurt language and people was possible through a return to traditional communities and the revival of the village. He was known for his active civic position and constant desire to draw the attention of the authorities to the problems of the Udmurt people.

On the day of his death, Albert Razin went on a solo picket in front of the State Council of Udmurtia. He held two posters in Russian. One read: “Do I have a homeland?”, and the other – a quote from the Avar poet Rasul Gamzatov: “If tomorrow my language disappears, then I am ready to die today”.

Before his self-immolation, Razin handed out to passersby his address to the State Council deputies about the situation with the Udmurt language. In this appeal, he proposed many measures to preserve the Udmurt language and ethnicity, including mandatory study of the Udmurt language in schools, bilingual signs and street names, and support for rural areas as custodians of traditional culture.

The tragedy of Albert Razin was the result of accumulated problems and disappointments. He was deeply concerned about the situation with the Udmurt language and culture, believing that they were in danger of disappearing. Razin repeatedly approached the authorities with proposals to improve the situation but often received only formal responses.

The scientist was convinced that modern “Udmurtophobia” contributed to the formation of a feeling of “inferiority” among the Udmurts and the spread of suicide. He linked the high suicide rate among the Udmurts with a feeling of being “second-class” and a lack of self-esteem.

Albert Razin’s self-immolation caused a wide public resonance. Several hundred people came to the Udmurt Theater to bid farewell to the scientist. Many speakers spoke in Udmurt, emphasizing the importance of his struggle to preserve national culture.

However, the reaction of the authorities was ambiguous. The head of the republic, Aleksandr Brechalov, commented on the situation only a day after the incident, calling Razin “a man who contributed to the development of culture and the Udmurt language”. At the same time, he called for refraining from speculation on the topic of national policy in the republic.

Albert Razin’s tragedy has intensified the discussion about the future of the Udmurt language and culture. The Udmurt Ministry of National Policy offers modern approaches to popularizing the language, such as Udmurt discos, blogger competitions, and Udmurt-language websites. However, Razin considered these initiatives superficial and insufficient.

Independent Udmurt activists such as Alexey Shklyaev advance their agenda by organizing lectures, making films, and translating. They face difficulties and attention from law enforcement agencies, reflecting the complexity of the situation with national movements in the region.

Preserving the Udmurt language faces many difficulties. In Udmurt cities, especially in Izhevsk, there are practically no signs in the Udmurt language, and Udmurt speech is rarely heard on the streets. Many parents, even in rural schools, do not choose to have their children study the national language, fearing that this could interfere with passing the Unified State Exam in Russian and entering universities.

Udmurts make up about 30% of the republic’s population, with most of them living in rural areas. In cities, Udmurts often assimilate, losing touch with their native language and culture.

The tragic death of Albert Razin became the final argument in his long struggle to preserve the Udmurt language and culture. Many consider his act not as suicide, but as a sacrifice for the sake of his people. Razin wanted to draw public attention to the problems of the Udmurt language and urge people to think about their attitude toward their native culture.

Despite its tragic nature, Albert Razin’s act made many people think about the fate of the small peoples of Russia and their languages. His struggle continues to inspire activists and scientists working to preserve national cultures.

The story of Albert Razin is the story of a man who was devoted to his people and their culture to the end. His tragic death became a symbol of the struggle to preserve the national languages and identity of the small peoples of Russia.