RECONCILIATION AGREEMENT BETWEEN GERMANY AND NAMIBIA:

A PATH TOWARDS REPARATION OF THE FIRST GENOCIDE OF THE 20TH CENTURY

The wounds inflicted by the great massacre of 60,000 Herero and 10,000 Namas in the former colony of Southwest Africa have yet to heal. Added to the concentration camps and slave labor, are the scars from the exhibition of human remains in museums and the manipulation for racist scientific theories. After a century of denial, the governments of both countries agreed to compensation of 1.1 billion euros over a period of 30 years. However, the descendants of the victims do not feel that their demands are heard.

On 28th May 2021 Germany issued an announcement that it had reached a Reconciliation Agreement with Namibia. This agreement acknowledged that it committed genocide against the Herero and Nama peoples in South West Africa (now Namibia) between 1904 and 1908. The agreement has yet to be confirmed by the German Bundestag (the German Federal Parliament) and the Namibian Parliament. The draft agreement represents one of the first times that a formal Reconciliation Agreement has been negotiated between a former colonial power and a former colony on a state-to-state level.

The genocide of the Herero and Nama began on 12th January 1904 after simmering tensions between German settlers and the residents of South West Africa with an attack by the Herero on German farmers and traders in Okahandja, Karibib, and Omaruru, with the primary aim of expelling the Germans from Ovahereroland. The Germans responded to this attack with massive brutality, murdering men, women and children.

An estimated 60,000 Herero and 10,000 Nama lost their lives at the hands of the German forces. It is not only about the number of lives lost, but also the social, economic and psychological impact.

The commander of the German forces, General Lothar von Trotha, issued an order on 2 October 1904 that amounted to an extermination declaration. Herero homesteads and cattle posts were attacked, and their residents annihilated. An estimated 60,000 Herero and 10,000 Nama lost their lives at the hands of the German forces. But as some of the victims of the genocide note, it is not only about the numbers of people lost but the social, economic, and psychological impacts that need to be considered.

The German forces attacked Herero who were gathered and seeking to negotiate a peace agreement at Omahakari (Waterberg) in central Namibia on 11 August 1904. Hundreds of Herero were killed outright, and many of those who escaped into the Omaheke Region to the east were hunted down and killed. An unknown number of Herero lost their lives due to thirst in their efforts to cross the Omaheke and flee into the Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana).

Annihilation, slave labor and destruction of their livelihoods

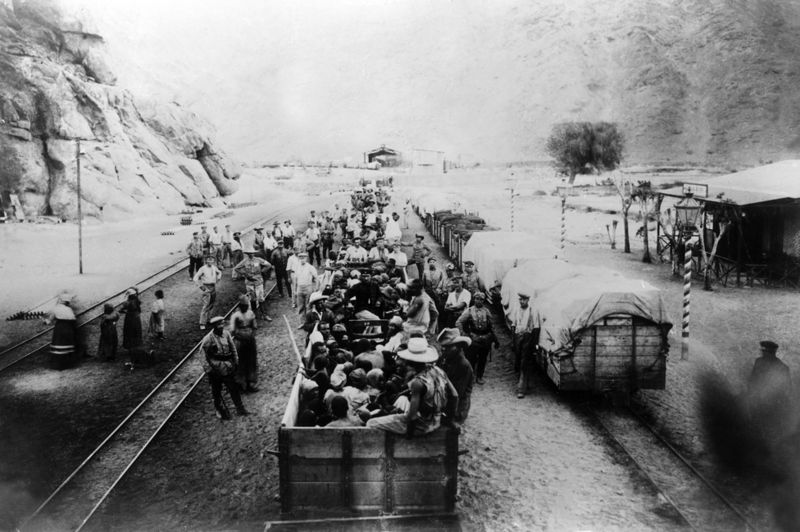

Outright massacres and murders of Namibia’s people by the Germans between 1904 and 1908 included not only Herero and Nama but also San and Damara. Thousands of Herero and Nama were confined to concentration camps where they experienced horrific living conditions, including lack of food, water, and medical attention. Others were forced into slave labor, building roads and railways, and working in mines and on German farms and ranches.

The genocide against the Herero and Nama had several phases. The first of these involved massacres of both combatants and non-combatants. The second phase consisted of the establishment of a cordon in the Omaheke region and hunting down and dispatching Herero refugees from the Battle of Omahakari. The third phase was the implementation of a scorched-earth policy aimed at destroying the livelihoods of the Herero and Nama; not only destroying homes, corrals, and sacred sites, but also capturing or destroying Herero and Nama cattle, goats and sheep and burning their crops.

The period between the cessation of formal war and the closing of the concentration camps in 1907-1908 did not see the cessation of hostilities, as the slaughter of Herero, Nama, and others continued until South African forces took over South West Africa and replaced the German colonial state in 1915. Although there was an overt effort by the German State to cleanse the archival records of evidence of genocide and massive human rights violations, efforts were made by victim groups to keep the knowledge of the first genocide of the 20th century alive and to commemorate the losses of Herero, Nama, San, Damara, and others.

Thousands of Herero and Nama were confined to concentration camps where they experienced horrific living conditions, including lack of food, water and medical attention.

One of the bitter reminders of the genocide was the presence of human remains of Herero, Nama and San in German museums, medical schools, and hospitals. Skulls, bones, and whole bodies were experimented on by German scholars over the next century. Some of the experiments were aimed at attempting to justify the racist scientific theories which underpinned German physical anthropological perspectives on race until the end of the Second World War and beyond.

In some cases, Herero and Nama human remains were put on public display in museums. There was a general outcry in the early part of the 21st century when the treatment of Herero and Nama remains became public, especially when stories were told of Herero women in the concentration camps at Luderitz and Swakopmund being forced to prepare the skulls of people who died in the camps for transport to German institutions.

There were some small measures of success, however, with, for example, Germany’s decision at the beginning of the 21st century to repatriate Herero and Nama skulls and other human and cultural remains to Namibia. The repatriation of these remains took place between 2011 and 2018 from German hospitals, museums, and other institutions. There were no formal apologies, however, for the ways in which the Herero and Nama human remains were dealt with while they were in German hands.

Seeking forgiveness without listening to descendants

On 14 August 2004, the German Minister for Development and Economic Cooperation, Heidemariee Wieczorek-Zeul, officially apologized at Omahakari, Namibia, for the atrocities that had been committed by German forces against the Herero and the Nama. Subsequently, other German government officials referred to the atrocities as a ‘genocide’ and sought forgiveness for their transgressions against the peoples of Namibia.

Germany negotiated only with the Namibian government in a series of meetings between 2015 and 2021 regarding how to handle the consequences of the genocide. There were virtually no negotiations with descendants of victim groups (the Herero and the Nama). Neither the Ovaherero Traditional Authority (OTA) nor the Nama Traditional Leaders Association (NTLA) were allowed to take part in the negotiations involving the reconciliation agreement.

Germany and Namibia provisionally signed an agreement that includes the payment of €1.1 billion over 30 years for development projects.

In May 2021, Germany and Namibia tentatively signed an agreement that includes the payment of €1.1 billion (US$1.3 bn) over 30 years for development projects in Namibia. The payment would be a kind of reconciliation fund that would provide financial, cultural, and other assistance to Namibia. The Herero and Nama rejected the financial offer as inadequate in public statements, but the Namibian government is considering accepting the offer.

The tentative plans of the Namibian government are to provide development assistance in 7 of the country’s 14 regions where the Herero and Nama represent a majority of the residents. There would be no payouts to individuals or communities, unlike, for example the recent reconciliation agreement of Australia, which has agreed to pay 75,000 Australian dollars (US $55,000) to some members of its Aboriginal population who were forcibly removed from their families as children.

No legal precedent, no land restitution

The draft Reconciliation Agreement stresses that Germany recognises the genocide in the moral and political sense. However, Germany’s position is that it has ruled out financial reparations to individuals for the genocide. What this means is that Germany does not want to set a legal precedent for paying reparations that might require the German government to provide financial compensation to victims of its colonial and post-colonial policies. Likewise, the agreement with Namibia can be a test case for future negotiations with the former French, British and Portuguese colonies in Africa.

One of the critical areas not mentioned in the Reconciliation Agreement was that of land, some of which is still in the hands of German Namibians. The Herero and Nama feel that land restitution should be considered in the Reconciliation Agreement, though the Namibian government has chosen not to support these requests. In 2020, Namibia issued a report on Ancestral Land Claims in the country in which it was argued that land could not be taken away from individuals who owned it without a ‘willing-seller-willing buyer’ agreement.

It remains unclear when Germany and Namibia will finalize the Reconciliation Agreement. What is clear is that the Herero and Nama and the San and Damara believe that the agreement does not contain the full range of what they feel they should receive in the form of reparations and compensation for the human rights offenses that they suffered –and continue to suffer– at the hands of the German colonial state. They feel strongly that the only way that reconciliation can be achieved is to have the descendants of victim groups participate fully in decision-making about how the gross human rights violations and their impacts should be addressed.

Robert K. Hitchcock is a professor of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico.

Melinda C. Kelly works at the Kalahari Peoples Fund.

Indigenous Peoples and Climate Technologies

Acknowledging indigenous peoples’ technologies and identifying linkages with Technology Needs Assessments

This guidebook is produced as part of the GEF-Funded Global Technology Needs Assessment (TNA) Project, which is implemented by UNEP and UNEP DTU Partnership. Since 2009, close to one hundred countries have joined the Global TNA Project.

Indigenous peoples’ knowledge of climate resilience and their global contribution to a sustainable management of our shared natural resources are critical to combating climate change and its impacts. Yet, their contribution often remains unacknowledged, and too often indigenous peoples have little access to the financial resources or forums for decision-making concerning the environment, which severely undermines opportunities for significant influence in climate policy, planning and action.

This guidebook provides information about how to identify and integrate relevant considerations on indigenous peoples and technologies into the TNA process, while ensuring that their free, prior and informed consent is obtained.

UN Human Rights Council adopts historic resolutions on the right to a Safe Environment, Climate Change and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Geneva, Switzerland, October 12, 2021: At the close of the UN Human Rights Council’s forty-eighth session on Friday, October 8, three resolutions in which the IITC had actively engaged were adopted. The right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment is now formally recognized at the global level through a resolution endorsed by over 1000 Indigenous Peoples, civil society organizations and UN Experts. This resolution affirms the right already recognized in Article 29 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The unbreakable link between human rights and a safe environment was further underscored by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) in its recommendations for the country review Mexico from 2015. The CRC asserted at that time that “Environmental Health” is a protected right under Article 24 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child in response to IITC’s submission addressing the devastating and deadly health impacts of toxic and banned pesticides on Yaqui Indigenous children in that county. As a result of the Human Rights Council’s landmark resolution, this is now recognized as a universal right.

Click here for a copy of the resolution as adopted.

In a second historic resolution, the Council created a new Special Rapporteur’s Office on the promotion and protection of human rights in the context of climate change. The urgent need for the creation of this new Special Rapporteur to gather information and report on human rights violations created by the causes, impacts and, in some cases, false market-based solutions to climate change generated broad support from Indigenous Peoples, small island States, civil society organizations, and other human rights mandate holders, including the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. IITC played an active role in the work of this broad coalition over the past year as a focal point for Indigenous Peoples in a number of webinars and educational fora, stressing its vital importance as the climate crisis continues to worsen.

Click here for a copy of the resolution as adopted.

Andrea Carmen, Executive Director of the International Indian Treaty Council (IITC) and member of the Facilitative Working Group for the UNFCCC Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform, warmly welcomed these historic advances, which affirm the understanding of Indigenous Peoples around the world that human health and well-being cannot be separated from a clean and healthy environment: “The adoption of these resolutions as a result of a broad collective effort will enhance the ability of Indigenous Peoples to present rights-based solutions for environmental recovery and restoration, and to protect the integrity of their natural ecosystems from environmental contamination and climate change, in line with their human rights. Too often throughout the UN system we have seen some so-called solutions promoted to address environmental degradation, biodiversity loss, deforestation and climate change that ignore, or even further violate the rights of Indigenous Peoples to protect their homelands and continue their ways of life. We hope that these decisions by UN Human Rights Council will help us chart a stronger rights-based course to ensure environmental protection and reverse climate change”.

In addition to these historic and long-awaited advances, the Human Rights Council’s resolution on Human Rights and Indigenous Peoples was also adopted on the last day of the session. This resolution also affirms the essential role of Indigenous Peoples in addressing climate change and biodiversity loss, and it addresses other closely-related concerns, including ending impunity for the repression of human rights defenders. IITC is also gratified that the resolution recognizes the importance of recent and upcoming studies by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous People and the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. It also provides a way forward to advance enhanced participation of Indigenous representative institutions, affirms a process for international repatriation of sacred items and human remains, and denounces violence against Indigenous women and girls, among many other important provisions.

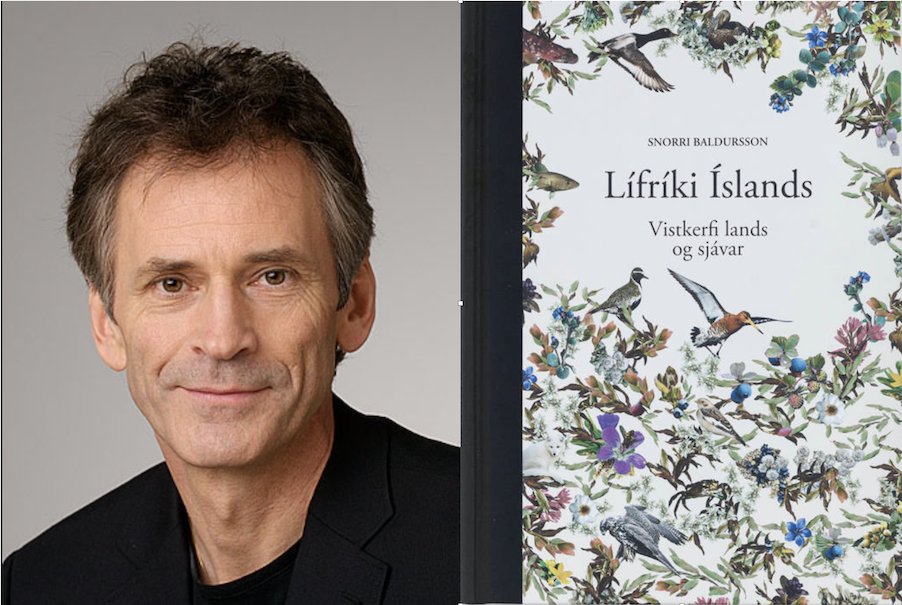

Snorri Baldursson passed away – Iceland and the Arctic lost its leading Ambassador for Conservation of Flora and Fauna

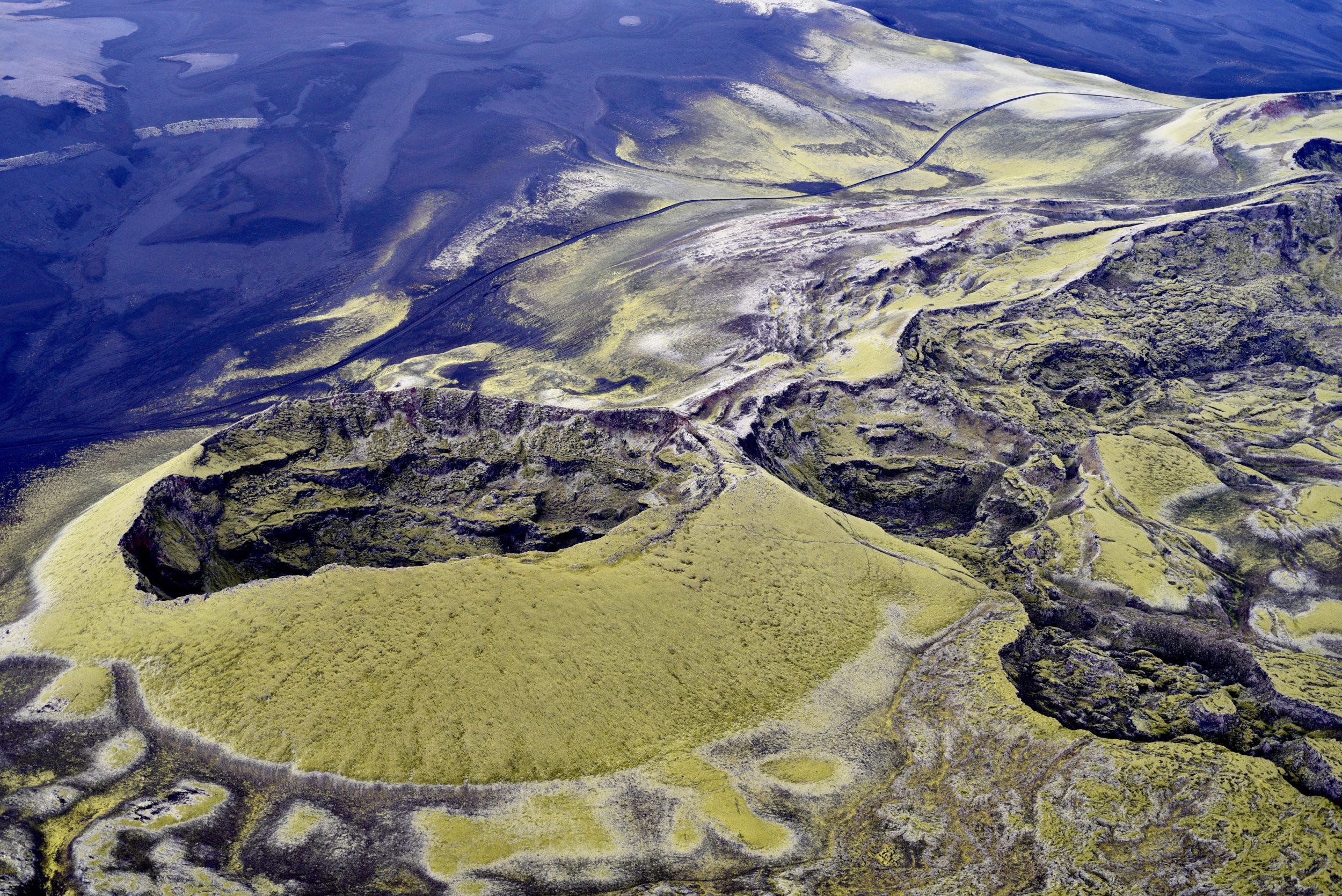

Snorri Baldursson passed away on September 29. We lost our member and close friend at the much too early age of 67. And Iceland and the Arctic lost its leading Ambassador for Conservation of Flora and Fauna. We remember him with his inspirational and motivating spirit from his time as head of the Arctic Council program on the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), or when we were meeting with him and colleagues from all over the Arctic in the Siberian Lena Delta discussing the future development of the Arctic Protected Area Network, or from his strong engagement for the protection of the Icelandic Highlands. His death is a major loss for the Icelandic and Arctic nature conservation movement, but his name will be closely related to the legacy he left us with the World Heritage Site Vatnajökull national park. And the best gift Iceland could provide in his honor would be if his dream of protecting the entire Icelandic Highland as a national park would be implemented in the near future.

Peter Prokosch

Let’s have a look at Snorri’s impressive life history provided by Arni Finnsson und Ólafur S. Andrésson:

Snorri Baldursson in memoriam

The Icelandic biologist, Dr. Snorri Baldursson, passed away at home in the early hours of 29th September. The cause of death was brain cancer.

Snorri was born 17th May 1954 at Akureyri Hospital in northern Iceland. He was raised at the farm Ytri-Tjörn in Eyjafjörður together with his siblings. In 1974 he finished High School in Akureyri and then finished undergraduate studies in biology in 1979 from the University of Iceland. He studied plant ecology and plant genetics for Masters Degree at the University of Colorado and finished his PhD degree at the University of Copenhagen in 1993.

After finishing his studies abroad Snorri became involved in research on land reclamation and conservation, focusing intensely on these subjects during the last 20 years. He was also active in nature conservation and wrote influential articles and books as well serving on the boards of NGOs and public institutions.

Snorri was director of CAFF from 1997 – 2002, then took a management position at the Institute of Natural History 2002 – 2008, and was the head ranger at the Vatnajökull Glacier Park and chairman of Landvernd, the Icelandic Environmental Association, 2015 – 2017. Finally, he served as director of the Department of Resources and Environment at the Agricultural University of Iceland from 2018.

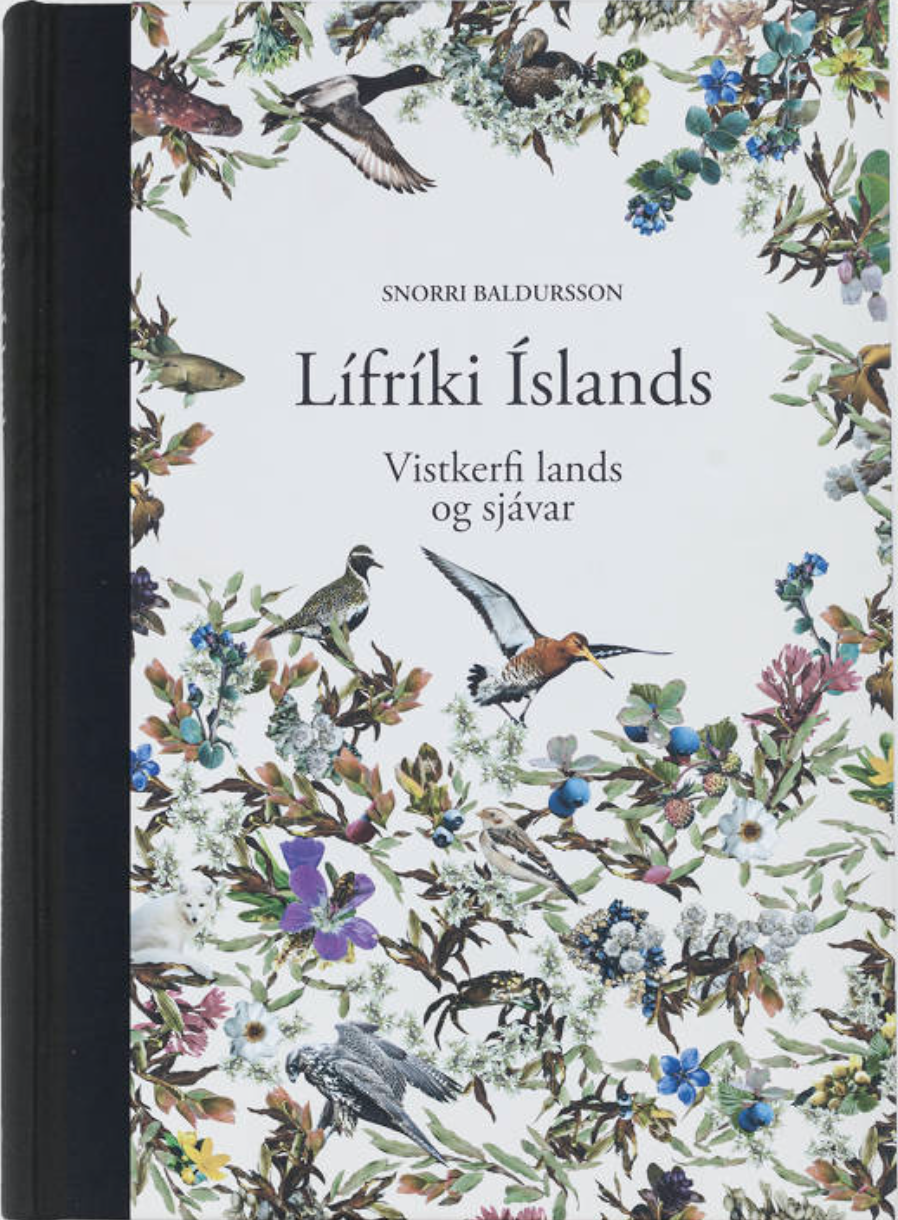

In 2014 Snorri published the book on the Flora and Fauna of Iceland for which he received the Icelandic Litterature Award in the category science and general interests. Then, last month Snorri published a book on Vatnajökull Glacier Park: World Treasure. The book was based on his work leading and editing Iceland‘s successful application for a UNESCO World Heritage Status for the Park, granted in 2019. For this Icelanders and the global conservation community are greatly indebted to Snorri and his excellent work.

Last summer Snorri established Skrauta, an NGO which campaigns for the protection of Vonarskarð, a very precious wilderness area at the centre of the Icelandic Highlands; an essential and successful undertaking, indeed.

In Iceland Snorri will be remembered for his legacy in nature conservation and communication, his cosmopolitan view on environmental issues, his inspiring books and teaching.

Snorri had four sons, Heimir born in 1974, Narfi Þorsteinn born 1982, Baldur Helgi born in 1986 and Snorri Eldjárn born in 1988. His surviving wife is Elsa Friðrika Eðvarðsdóttir.

A Problem of Moscow’s Own Making: Who is an Indigenous People in the Russian North?

Paul Goble

Staunton, Sept. 27 – The Russian government has defined as indigenous peoples in the North those who are members of one of 40 numerically small peoples (under 50,000 each) who receive benefits from the government which allow them to continue to practice their traditional hunting and fishing.

That approach has given rise to two sets of issues, one of which threatens to become explosive. The first involves those who are members of these numerically small peoples but who live in cities and do not live in a traditional manner. Some of them want to claim that status, but Moscow has been working hard to deny them such an opportunity and the money it involves (windowoneurasia2.blogspot.com/2020/10/moscow-sets-up-registry-of-northern.html and windowoneurasia2.blogspot.com/2020/11/saami-activist-appeals-to-supreme-court.html).

While this is a problem for some individuals and for the defense of national identities of these groups, it does not present serious difficulties for large numbers of people or Moscow as such. But the second issue does. The indigenous peoples in the Russian North are proud of that status and want to distinguish themselves from everyone else, including ethnic Russians.

On the one hand, that has prompted some Russian nationalists to demand that the numerically small peoples of the north not be allowed to make a distinction that exists in Russian law. And on the other, it has led some Russian nationalists to demand the Russians living in the North be named an indigenous people as well and get benefits too (windowoneurasia2.blogspot.com/2019/12/to-protect-national-security-moscow.html and windowoneurasia2.blogspot.com/2021/09/russian-nationalist-outraged-russians.html).

Moscow-appointed officials in the North not surprisingly are on the side of the Russians, although they face problems with the fact that Russian law itself defines indigenous peoples for the purpose of promoting the survival of these traditional communities and thus cannot oppose that without putting themselves in opposition to Moscow.

But they may now have found a way to take action against the numerically small indigenous nationalities of the Russian North. Some of them are suggesting that foreign countries want to mobilize these communities by using the indigenous-non-indigenous divide and that Moscow must block that by ending this arrangement (regnum.ru/news/society/3381878.html).

This debate appears set to escalate with the non-Russians who benefit playing defense and the ethnic Russians and their corporate allies in the North playing offense and hoping to use the national security card to get Moscow’s attention and support for ending what has been one of the few defenses the indigenous peoples have.

If the Russian side wins this debate, however, anger among the numerically small indigenous nations of the North will escalate; and it is not beyond the realm of possibility that the Russian government by its willingness to cater to Russian nationalists on this question may be putting itself at far greater risk than it likely understands.

The traditional peoples are armed, and many of them work as prospectors for natural resources and even have dynamite to search for rare minerals. Angering people with guns and explosives is far from the cleverest thing to do when they are located in critical regions with long and unguarded pipelines and highways.

But if the indigenous peoples of the North succeed, they will become a model for other non-Russians who are likely to see playing up the difference between their own nations and ethnic Russians who arrived during imperial expansion as politically useful. That could create an even more serious problem for Moscow as well.

Russia: Siberian shaman who marched against Putin is indefinitely confined to a psychiatric hospital

Responding to a court decision that came into force today to indefinitely confine Siberian shaman, Aleksandr Gabyshev, to a psychiatric ward for vowing in 2019 “to purge” President Vladimir Putin from the Kremlin, Natalia Zviagina, Amnesty International’s Moscow Office Director, said:

“Aleksandr Gabyshev has become a symbol of grassroots resistance to the increasingly repressive government of Vladimir Putin, so it is not surprising that the authorities went to such extreme lengths to silence him and smear his name. Once again, the authorities are using ‘psychiatric care’ as a punishment – a method tried and tested during Soviet times.

“It is genuinely shocking to see how easily the life of someone who dares to peacefully express their views and criticize the authorities is destroyed by the powerful and repressive tools of the state.

“Compulsory psychiatric treatment is a form of torture and other ill-treatment. The authorities must refrain from any involuntary therapy and release Aleksandr Gabyshev immediately and unconditionally, as he has been sentenced to indefinite compulsory psychiatric treatment solely for peacefully exercising his right to freedom of expression. The use of punitive psychiatry as a method to silence dissent must stop now.”

BACKGROUND

Today, an appeal by Aleksandr Gabyshev was unsuccessful and the decision on indefinite forced hospitalisation has been upheld.

On 26 July, the Yakutsk City Court ruled that Aleksandr Gabyshev must be confined indefinitely to a psychiatric hospital for compulsory “intensive” treatment. Today the court decision came into force after his defence team lost their appeal. The court declared Aleksandr Gabyshev “insane” and lacking legal capacity, and was found guilty of “using violence against police officers” and “calling for extremism”.

In 2019, Aleksandr Gabyshev became widely known after he walked hundreds of kilometres from Yakutsk to Moscow, promising to use his self-proclaimed magic powers to “purge” President Vladimir Putin from the Kremlin. In September 2019, after travelling around 3,000 km – over a third of the way to Moscow – he was abducted by police and accused of suspected “public calls for extremism”, then briefly placed in a psychiatric hospital for examination. He was released two days after, only to be forcibly hospitalized again in May 2020 – this time purportedly because he refused to be tested for Covid-19. He was released two months later after public outcry, and an international campaign of solidarity, which Amnesty International took part in.

In January 2021, two weeks after Aleksandr Gabyshev announced another march on the Kremlin, 50 police officers broke into his house, arrested him and took him to a psychiatric hospital. This time he was officially charged with making “calls for extremism” and “using violence against police officers”. During his arrest, Gabyshev allegedly tore a riot officer’s uniform and superficially wounded him with a batas, a ceremonial Yakut sword.

Mining Energy-Transition Metals: National Aims, Local Conflicts

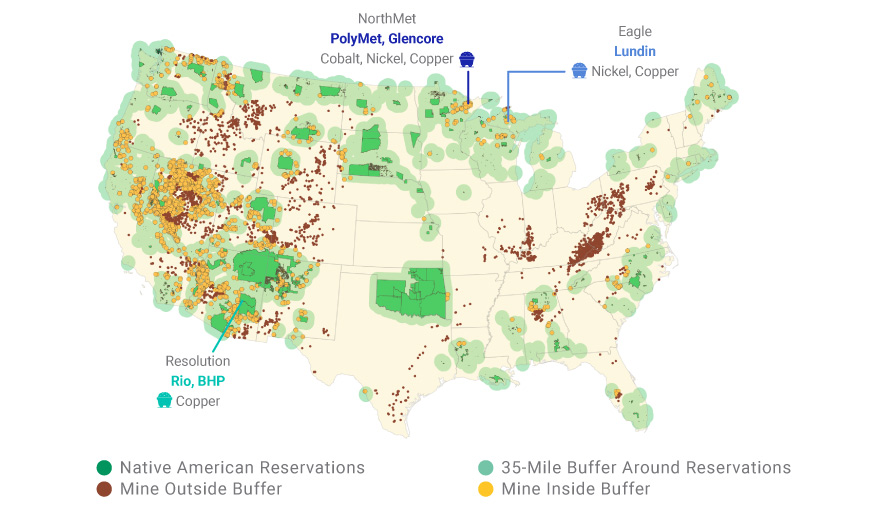

- Many of the remaining untapped deposits of the metals critically needed for U.S. energy to transition from fossil fuels are located either near or within areas of cultural and environmental importance to Native Americans.

- Among these key energy-transition metals, 97% of nickel, 89% of copper, 79% of lithium and 68% of cobalt reserves and resources in the U.S. are located within 35 miles of Native American reservations.

- Mining companies have already faced opposition to mine development in many of these areas, reflecting the heightened risk to companies and investors arising from these conflicting priorities.

With the Biden administration seeking to slash U.S. greenhouse-gas emissions and support a rapid move to electric vehicles and renewable-energy technology,1 many investors are looking closely at the metals needed in new energy technologies. Copper is one key metal, and its demand may rise as much as 350% by 2050, according to one estimate.2 For investors looking through an ESG lens, however, not all metal mines are created equal or pose the same risks. Some mining projects, while providing metals key to addressing the global challenge of transitioning away from fossil fuels, may face strong and increasing opposition from Native Americans for threatening sacred areas or traditional ways of life.3

Not only could local cultures be at risk, but investors too. Local opposition increases risks that a mining asset could lose its license to operate and its value to investors. The risks may be even greater since the new administration, in its election materials, has indicated that protection of Native American culture is a priority.4 COVID-19’s devastating impact on Native Americans5 was a sad reminder of the disparities faced by many Native American communities.

Key Mines Are Located Near Native American Reservations

We analyzed 5,336 U.S. mining properties in the S&P Global Market Intelligence database (as of March 15, 2021) and found the majority of U.S. reserves of cobalt, copper, lithium and nickel are located within 35 miles of Native American reservations. The same is true for the total count of U.S. mines with primary commodities of copper, lithium and nickel.

US Transition-Metal Reserves Within 35 Miles of Native American Reservations

Most of these mines are not located on Native American reservations. But for people with a history of being forced onto settlements, many of which have been compressed over time, culturally significant areas are not limited to reserved lands. We looked at all mines located within 35 miles of a reservation, noting that two prominent mining projects facing strong opposition from Native American groups – Lundin Mining’s Eagle mine in Michigan and the Resolution copper mine in Arizona – are both less than 35 miles away from the nearest reservation.

The Resolution mine, owned jointly by Rio Tinto (55%) and BHP Billiton (45%), has already spent over USD 2 billion on development and permitting.6 It could eventually supply up to a quarter of the country’s copper demand.7 However, Native American communities such as the San Carlos Apache have opposed the alleged threat it poses to the Chich’il Bildagoteel, otherwise known as Oak Flat, a place with spiritual significance to the Apache for generations.8

US Mines’ Proximity to Native American Reservations

Rio Tinto already experienced a stakeholder uproar and harsh repercussions after a failure to protect places of indigenous significance in May 2020, albeit on the other side of the world. Three executives, including the CEO at the time, were forced to leave the company, among other leadership changes, after the company bulldozed the ancient Juukan Gorge rock shelters, a site of both indigenous and archaeological value in Australia.9

There, as at the Resolution mine, the company obtained government approval to move on the areas of concern, putting sacred areas at risk. Nonetheless, civil-rights activism, social-media scrutiny and the momentum for social justice have amplified calls to defend indigenous cultures. Scenarios where mines obtained permits — only to have them later taken away, after much investment, due to alleged failures to address indigenous issues — have played out around the globe in recent years. A stronger focus on local concerns may be warranted.

1“Fact Sheet: President Biden Sets 2030 Greenhouse Gas Pollution Reduction Target Aimed at Creating Good-Paying Union Jobs and Securing U.S. Leadership on Clean Energy Technologies.” White House, April 22, 2021.

2Elshkaki, A., Graedel, T.E., Ciacci, L., and Reck, B. “Copper demand, supply, and associated energy use to 2050.” Global Environmental Change, June 22, 2016.

3Davidse, A. And Guzek, J. “Trend 10: Meeting demand for green and critical minerals.” Deloitte Insights, Feb. 1, 2021.

4“Biden-Harris Plan for Tribal Nations.” JoeBiden.com.

5An estimated 1 in 475 Native Americans died from the disease. “COVID’s Assault on Native Americans.” The Week. March 7, 2021

6“History.” ResolutionCopper.com. Accessed March 22, 2021.

7“Land Exchange.” ResolutionCopper.com. Accessed March 23, 2021.

8“San Carlos Apache Tribe Sues US Forest Service to Stop Resolution Copper Mine.” San Carlos Apache Tribe, Jan. 15, 2021.

9Butler, B. and Wahlquist, C. “Rio Tinto investors welcome chair’s decision to step down after Juukan Gorge scandal.” Guardian, March 2, 2021.

Alaska activist and model Quannah Chasinghorse makes waves at Met Gala and New York Fashion Week

In a shining gold dress adorned with a family friend’s turquoise earrings, necklaces and bracelets made by Native artists, 19-year-old Quannah Chasinghorse turned heads at her first Met Gala — thestar-studded annual fundraiser and haute couture spectacle held Monday at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

The Indigenous activist and model from the Native Village of Eagle wore a dress by designer Peter Dundas for this year’s theme, “American Independence.” Chasinghorse, who is Han Gwich’in and Oglala Lakota, was photographed on Monday alongside celebrities throughout the night including Mary J. Blige, Megan Fox and Kris Jenner.

Chasinghorse has had a busy year, attracting the attention of some of the highest names in fashion. Vogue magazine recently featured her in an article titled “Thrilling Ascent of Model Quannah Chasinghorse,” which called her “one of modeling’s freshest new faces” and said she “is breaking barriers in an industry that has long overlooked Indigenous talent.”

By late Monday, social media was buzzing about Chasinghorse.

“WHY ISNT ANYONE TALKING ABOUT THIS INDIGENOUS QUEEN WHO SERVED AT THE MET GALA,” Twitter user @takahashiputa said in a post, which garnered more than 300,000 likes. “HER NAME IS QUANNAH CHASINGHORSE AND SHE ATE.”

“Indigenous Model Quannah Chasinghorse Is The Met Gala Queen & No, We Won’t Be Taking Questions,” entertainment website Pedestrian wrote about Chasinghorse’s look. Another website, Refinery29, called her the “breakout star” of the event.

Twitter user @WambliEagleman wrote, “Quannah ChasingHorse (is) representing all Natives at the #MetGala tonight!”

In one of her first posts to Twitter — she already had more than 30,000 followers on that platform as of Tuesday afternoon, and more than 100,000 on Instagram — Chasinghorse said she wanted to “represent Indigenous art and fashion” for this year’s theme.

“I felt very alone there but some people were very sweet to me,” Chasinghorse said. “The Met Gala was a dream.”

Jody Potts, Chasinghorse’s mother, said her college best friend, Jocelyn Billy Upshaw — who was Miss Navajo Nation in 2006 and has known Chasinghorse since she was born — was flown out to New York with her personal jewelry collection.

Upshaw, Potts and Chasinghorse Facetimed with the designer and stylist to help dress Chasinghorse for the gala, Potts said.

Chasinghorse also made her debut at New York Fashion Week, closing for designer Prabal Gurung and walking for Jonathan Simkhai.

The model also walked for brand Gabriela Hearst, opening and closing the runway show.

In May, Chasinghorse was featured in a 20-page Vogue Mexico spread, which showcased her activism and need for accurate representation in modeling. She was also recognized in Teen Vogue’s 21 Under 21 list highlighting young girls and femmes, and in The Chanel Book’s 2021 issue.

She is known for her advocacy surrounding the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and was influential in pushing the Alaska Federation of Natives to declare a climate change emergency at its annual convention in 2019.

Elon Musk drives through loophole by launching Tesla on tribal land

Tesla opened its first facility in New Mexico this week in partnership with the Nambé Pueblo.

Electric car manufacturer Tesla opened up its first sales and service center in New Mexico this week thanks to a first-of-its-kind partnership with a tribal nation.

New Mexico has laws on the books that prohibit car makers from selling directly to customers without going through third-party dealerships. The law has prevented Tesla from establishing an official presence in the state over the years.

But now Tesla has found a way around that. The electric car maker partnered with the first nation of Nambé Pueblo to open its first facility inside a defunct casino on tribal land north of Santa Fe, where the state law does not apply.

The facility opened Thursday with tribal leaders and state lawmakers in attendance who praised the deal.

“This location will not only create permanent jobs, it is also part of a longterm relationship with Tesla. As the company is working with pueblo nambe to provide education and training opportunities for tribal members, as well as economic development,” Nambé Pueblo Gov. Phillip Perez said during the opening, according to KRQE.

Democratic Sen. Martin Heinrich (D) said it was a step toward decarbonizing the country’s transportation infrastructure and expanding access to electric vehicles.

“We need to double down on this progress and expand uncapped consumer incentives for electric vehicles, make it easier to manufacture electric vehicles in the United States, and fund the rapid electrification of the federal fleet of vehicles,” Heinrich said in a statement.

SHELL OIL LOOKS TO BE A LEADER IN ELECTRIC VEHICLE CHARGING

What exactly does the oil industry have in store for charging companies?

It sounds like the perfect plot for a conspiracy thriller: the giant oil companies are buying up electric vehicle charging companies as fast as they can. Do they mean to shut ‘em all down, or just to make sure that the price of charging is high enough that driving an EV won’t deliver any savings over driving a fossil-fueled vehicle? (Shell is one of the world’s largest providers of hydrogen, made from natural gas.)

Or, could there be a surprise ending? Perhaps the oil execs have the good of mankind at heart—they realize that the Oil Age is ending, and want to be in position to profit from the next energy era.

We’ll have to wait for the next episode to find out about that—what we do know is that three Europe-based oil multinationals (Shell, Total and bp) started getting into the charging game back in 2017, and now own companies at every stage of the charging value chain.

Shell is rapidly becoming a major player in the UK charging market—the company now offers charging at numerous petrol stations (aka forecourts), and will soon be rolling out charging at some 100 supermarkets.

The latest news is that Shell aims to install 50,000 on-street public charging points in the UK over the next four years (as reported by The Guardian). Earlier this year, the oil giant acquired ubitricity, which specializes in integrating charging into existing street infrastructure such as lamp posts and bollards, a solution that could make EV ownership more attractive to city dwellers who don’t have private driveways or assigned parking spaces.

This is a big deal—according to the UK’s National Audit Office, over 60% of urban households in England do not have off-street parking, meaning that there’s no practical way for them to install a home charger. A similar situation prevails in many regions, including China and parts of the US.

In the UK, local councils have emerged as something of a bottleneck for installing public charging. Shell has a plan to get around this by offering to pay the upfront costs of installation not covered by government grants. The UK government’s Office for Zero Emission Vehicles currently pays up to 75% of the installation cost for public chargers.

“It’s vital to speed up the pace of EV charger installation across the UK and this aim and financing offer is designed to help achieve that,” Shell UK Chair David Bunch told The Guardian. “We want to give drivers across the UK accessible EV charging options, so that more drivers can switch to electric.”

UK Transport Minister Rachel Maclean called Shell’s plan “a great example of how private investment is being used alongside government support to ensure that our EV infrastructure is fit for the future.”

Shell continues to invest in clean-energy businesses, and has pledged to make its operations net-zero-emissions by 2050. However, it has shown no intention of scaling back its oil and gas production, and some environmental activists are not convinced. Recently, members of the group Extinction Rebellion activists chained and/or glued themselves to railings at London’s Science Museum to protest Shell’s sponsorship of an exhibition about greenhouse gases.

“We find it unacceptable that a scientific institution, a great cultural institution such as the Science Museum, should be taking money, dirty money, from an oil company,” said Dr Charlie Gardner, a member of Scientists for Extinction Rebellion. “The fact that Shell are able to sponsor this exhibition allows them to paint themselves as part of the solution to climate change, whereas they are, of course, at the heart of the problem.”