ICIPR statement against intimidation of indigenous delegates by the Russian state’s representative during the EMRIP 15th session in Geneva

Dear delegates of the Expert Mechanism session!

Dear indigenous sisters and brothers and distinguished states’ representatives!

This is a statement regarding the fact of intimidation of Mrs. Yana Tannagasheva during the 15th session of the UN Expert Mechanism on the rights of indigenous peoples by the state’s representative.

By this statement, we would like to express our strong protest against the fact of intimidation of the member of the Russian indigenous delegation Mrs. Yana Tannagasheva (who represents the International Committee of indigenous peoples of Russia), by the representative of the Russian state’s delegation that was happened yesterday (4th July) during the first day of the session of the UN Expert Mechanism on the rights of indigenous peoples just in this room.

We consider yesterday’s aggressive dialog of the representative of the Russian state with Mrs. Yana Tannagasheva, including an attempt to find out her personal data, as a pure fact of intimidation of indigenous rights defenders considering our long negative practice in that field with Russian officials.

We consider the intimidation of indigenous people’s rights activists, which is unfortunately usual practice today for Russian authorities, unacceptable, especially if indigenous rights defenders are persecuted for their cooperation with the UN or for delivering information about indigenous rights violations to the UN human rights bodies.

We ask for the assistance of the Expert Mechanism and secretariat to prepare the official complaint with regards to the aggressive behavior of the member of the Russian state delegation against Mrs. Yana Tannagasheva. We also ask Expert Mechanism and the Human rights Council in general to protect indigenous rights defenders who are intimidated by Russian or any other authorities for their human rights activity and cooperation with the UN.

We express our solidarity to our indigenous brothers and sisters in Russia, Ukraine and other countries who fight for their freedom or against violations of indigenous rights by states or any other institutions, including business corporations.

Thank you for your attention!

Dmitry Berezhkov, International Committee of indigenous peoples of Russia (ICIPR).

The Arctic Council Pause: The Importance of Indigenous Participation and the Ottawa Declaration

The ongoing boycott of the Arctic Council – announced by the seven democratic member states (A7) three months ago on 3 March 2022 – was unexpected news to the six Permanent Participant organizations representing the indigenous peoples of the Arctic. While the Council is predicated upon the spirit of meaningful and inclusive participation of Arctic indigenous peoples, who hold special status under the foundational terms of the 1996 Ottawa Declaration, the Permanent Participants were not consulted before this historic boycott of Council meetings was announced after Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine.

The Arctic Council: An Innovative and Inclusive Diplomatic Forum for Aligning Indigenous and State Interests

The Arctic Council (like the Arctic region generally) is distinctively collaborative, where indigenous peoples and sovereign states regularly meet to jointly deliberate and collectively govern, embracing a region-wide commitment to co-management. This unity is its essence, a reflection of the prominent role of indigenous peoples in the Arctic order and the high value placed on indigenous values by not just indigenous peoples but their state and non-state colleagues on the Council as well.

While the Council does not de jure address matters of national security and defense, its distinct composition and high regard for indigenous knowledge and values has positioned the Council to de facto redefine Arctic security to include environmental, ecological, cultural and human security as core security pillars in the Arctic. Its embrace of indigenous values has helped the Council strengthen not only its East-West bond, but its North-South bonds as well, nurturing the emergence of a distinct culture of collaborative Arctic sovereignty and security over its first quarter century.

The omission by the A7 of their all-important commitment to consult with the six Permanent Participants ahead of the Arctic Council boycott decision signals a return to a more Westphalian conceptualization of Arctic security, risking an erosion of the hard-won prominence of indigenous voices in Arctic international relations. Indeed, this sacrosanct collaboration between tribe and state at the top of our world is now at risk.

Indeed, this sacrosanct collaboration between tribe and state at the top of our world is now at risk.

A Return of Indigenous Exclusion as Arctic Security Hardens?

While the unprecedented inter-state unity and protracted nature of the A7’s boycott of the Council made headlines, the exclusion of indigenous stakeholders in their deliberations prior to the boycott indicates a tectonic shift in Arctic governance is under way, as conceptions of Arctic security shift back from ‘soft’ power to ‘hard’ in the wake of Russia’s assault on Ukraine.

As described in a February 14 press release issued by the Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC), (AAC), one of the six indigenous Permanent Participant organizations of the Arctic Council, the Council is comprised of “[e]ight Arctic states, including the United States, Canada, and Russia and six permanent participants (Indigenous Peoples)” [1] which, together with a growing cohort of state and non-state observers:

“serves as the leading forum for the Arctic …” “that promotes cooperation, coordination, and interaction among the Arctic states and permanent participants. It is at the Arctic Council table that international cooperation agreements have been reached that address important areas including climate change, marine pollution, and Arctic scientific study. It also serves as an important global forum working towards agreements committed to sustainable solutions as regions look to future developments in the Arctic.” [2]

Ten days before the Ukraine invasion began, AAC called upon world leaders to remember their commitments to the indigenous peoples, noting in particular that Crimean Tatars “comprise the largest population of Indigenous Peoples in Ukraine” as “officially recognized by the Government of Ukraine and the European Parliament as Indigenous Peoples in February 2016.” [3] With the winds of war blowing, AAC was thus:

“urging global leaders in Canada, United States, Russia, and Ukraine not to forget commitments they have made to Indigenous Peoples. Specifically, AAC wants to remind state leaders that Canada, United States and Ukraine are all party to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), originally adopted in 2007. AAC points to Article 30 which states: ‘Military activities shall not take place in the lands or territories of indigenous peoples, unless justified by a relevant public interest or otherwise freely agreed with or requested by the indigenous peoples concerned,’ Further it proclaims: ‘States shall undertake effective consultations with the indigenous peoples concerned, through appropriate procedures and in particular through their representative institutions, prior to using their lands or territories for military activities.’” [4]

Chief Gary Harrison, AAC’s International Chair, pointed out the vital importance of the work of the Arctic Council, and the potential risk to the hard-earned diplomatic alignment of Arctic states and indigenous peoples, strengthened by their unity of effort and purpose in combating Arctic climate change at the Arctic Council table:

“We have warming taking place in the Arctic at three times the speed of other global jurisdictions. This reality and the future threat to Arctic water systems, marine life, wildlife, and our fragile ecosystems will affect us here in the Arctic, and globally, for generations to come. The work now at the Arctic Council table is already at a critical stage. Our relationship with the Russian Federation, as with all our regional partners, is one of diplomatic cooperation that took years to build. We fear this could be greatly disrupted if the resistance to finding a solution over the conflict in Ukraine continues.” [5]

And Chief Bill Erasmus, the AAC’s Canadian Chair, added that: “We want to remind all governments that the Arctic Council is the world’s only forum where we, as Indigenous People have inclusion at a global level. As concerns over the Russian-Ukraine crisis are increasing, we feel the need to speak out.” [6]

Erasmus emphasized the importance UNDRIP, which “must be adhered to through this process. The loss of human life, the economic and environmental costs should a war commence, is troubling. We do not support or endorse any war and urge all parties to seek a diplomatic solution.” [7] He also noted there were “several upcoming meetings set to take place that involve Indigenous Arctic organizations including Arctic Territory of Dialogue 2022,” originally scheduled (before the Arctic Council pause was announced) to be hosted by the Russian Federation in St. Petersburg in April. [8]

A Diverse Range Indigenous Perspectives on the Ukrainian War and the Arctic Council Pause

AAC’s effort to directly reach out – not only to the leaders of the Arctic states but the global community of nations – to protect the rights of indigenous peoples from the ravages of war reflects the powerful diplomatic innovation of the Arctic Council, the inclusive diversity inherent in the Council structure, and the novelty of its effort to align the formal sovereign powers of the Council’s state actors with the informal influence of its indigenous actors in the formation of Arctic policies.

While most (but not all) the Permanent Participants would endorse the boycott after it was announced, they did so with concern for the future of Arctic cooperation, knowing full well how great indigenous gains have been since the Council’s formation, and how much Arctic indigenous peoples have to lose in a world without an Arctic Council.

The Russian section of the Saami Council (SC) issued its own statement on 27 February, among the first, commenting they could neither “ignore” nor “remain silent” about the situation in Ukraine, and while not directly addressing “who is right and who is wrong” concluded there was “no justification for military action.”[9] Amidst the dizzying cascade of sanctions, suspensions, and boycotts of Russian participation in various forms of international cooperation since the war began, the SC’s Russian section expressed their desire

“to make sure that the Sami people from the Russian side can continue to participate in international meetings and conferences, including visiting other countries. … Now, more than ever, the Sami people in Russia need international support to continue cooperation between the Sami of the four countries. We hope that this difficult situation will soon be resolved in the least painful way.”[10]

Gwich’in Council International (GCI) issued its response to the pause, “Re: Joint Statement on Arctic Council Cooperation Following Russia’s Invasion Ukraine,” on March 3, in which GCI “welcomes the collective pause of activities of the Arctic Council as we explore new modalities for pursuing peace and cooperation in the north,” while expressing its

“grave concern for the people of Ukraine, particularly the indigenous peoples, due to the invasion by Russia. We stand with our partners around the world in calling for peace in Ukraine, a peace which can only be achieved by Russia recalling its armed forces immediately.”[11]

GCI reiterated that it

“remains committed to engage in productive dialogues that advance the collective aim and responsibility of stewarding a peaceful Arctic region built on cooperation and our shared value of mutual respect.”[12]

Four days later, the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) released its “Statement from the Inuit Circumpolar Council Concerning the Arctic Council,” which acknowledged the A7’s “calling for a temporary pausing of participation at all meetings of the Arctic Council and its subsidiary bodies,” as well as a “message from the Russian Chair of the Arctic Council agreeing to the request of the other countries.”[13] In their statement, ICC recounted that it:

“emerged from the Cold War as a unifying voice for Inuit across our collective homeland of Inuit Nunaat. We worked hard to ensure that our sisters and brothers from Chukotka were able to join us in 1992. We are concerned about the future of the Arctic Council which is based on peaceful cooperation and mutual respect. Inuit are committed to the Arctic remaining a zone of peace, a phrase coined by former USSR President Mikhail Gorbachev in a 1987 speech in Murmansk. ICC has repeatedly echoed this message in all of its guiding documents … ICC is monitoring the situation closely and agrees with the SAOs that this temporary pause will allow time to consider ‘the necessary modalities that can allow us to continue the Council’s important work in view of the current circumstances.’”[14]

how will the Council reconcile the interests of indigenous peoples and modern states if it can’t find a way to bridge the gaps in ideologies and governing philosophies separating the A7 from its circumpolar neighbor, Russia?

The Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON), widely criticized in recent years for rubberstamping the policies of the Russian Federation, issued its own statement on March 1, in which it took Moscow’s side:

“Respected Vladimir Vladimirovich! A peaceful sky, land of our ancestors and the safety of children – nothing can be more important for every inhabitant of our planet. For everyone. No exceptions. Regardless of ethnicity or native language. The North, Siberia, and the Far East remembers with gratitude those who have dedicated their destinies to the formation of our regions. … Peacemaking is never easy. [RAIPON] supports your aspiration and decision to protect the rights and interests of the residents of the Donetsk and Luhansk Peoples Republics and the security of a multiethnic Russia. We, representatives of 40 small indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East express hope for quick mutual understanding to ensure peace and harmony.”[15]

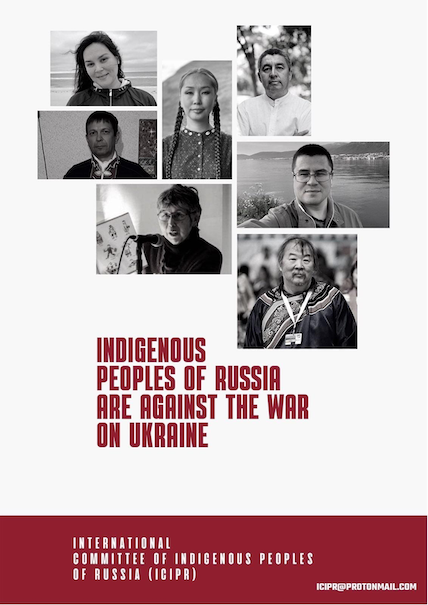

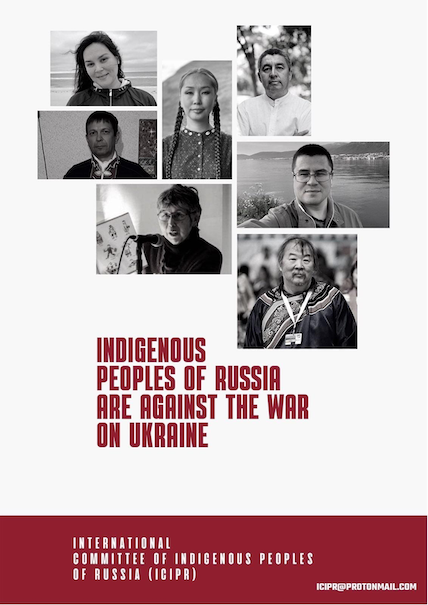

Ten days later, on March 11, the newly formed International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia put out its own statement rebutting RAIPON, signed by seven indigenous leaders in exile from Russia, and contrasting greatly with RAIPON’s endorsement of Putin’s aggression:

“WE – the undersigned representatives of the Indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East living outside of Russia against our will—are outraged by the war President Putin has unleashed against Ukraine … As representatives of Indigenous peoples, WE express solidarity with the people of Ukraine in their struggle for freedom and are extremely concerned about ensuring the rights of Indigenous peoples during the war on Ukrainian territory, including the Crimean Peninsula that remains illegally occupied by Russia. As representatives of Indigenous peoples, WE are outraged by statements of the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) on March 1, 2022 and the statement of civil society leaders on March 2, 2022 in support of the decisions of President Putin.”[16]

ICIPR called upon the international community (including the Arctic Council in addition to the UN) “to ignore the statements of RAIPON representatives and spokespeople of other organizations which supported Vladimir Putin’s decisions.”[17] The fate of RAIPON, and the challenge presented by ICIPR, remains uncertain, as does when and where the Arctic Council will resume meeting, and with whom.

Finding a path back to a restoration of the Council’s important, indeed sacred, reconciliation of tribe and state, is imperative

Will the Council bifurcate along the old East/West fault line, with the A7 representing a “free” Arctic exclusive of the vast Russian Arctic? Will the Council eventually find its way back together, either during or after the war in Ukraine comes to an end? In its future form, how will the Council reconcile the interests of indigenous peoples and modern states if it can’t find a way to bridge the gaps in ideologies and governing philosophies separating the A7 from its circumpolar neighbor, Russia?

The Arctic Council has since its inception in 1996 been about more than Arctic states. Its distinct contribution to statecraft has been rooted in its diverse, multilevel collaboration between indigenous peoples from across the circumpolar world, working in partnership with a diverse group of states – from microstates to middle powers to superpowers, and from democracies to colonial-states to autocracies. Together, they have reimagined statecraft as a synthesis of national and indigenous interests, and Arctic security as a distinctively northern synthesis of hard and soft security interests.

Finding a path back to a restoration of the Council’s important, indeed sacred, reconciliation of tribe and state, is imperative – ideally, with all eight founding member states and the six Permanent Participants all at the table once again – providing the world with an innovative, inclusive, and importantly viable, model for inclusive and responsible statecraft.

References

[1] Arctic Athabaskan Council, “Press Release: Conflict Continues in the Crimean Peninsula, Ukraine,” ArcticAthabaskanCouncil.com, February 14, 2022 (March 1, 2022), https://arcticathabaskancouncil.com/conflict-in-the-crimean-peninsula/

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Russian Section of the Saami Council, “The Russian section of the Saami Council has issued a statement regarding the current situation in Russia (27.02.2022),” SaamiCouncil.net, February 27, 2022, https://www.saamicouncil.net/news-archive/statement-by-the-russian-side-of-the-saami-council-regarding-the-current-situation-in-russiaa

[10] Ibid.

[11] Gwich’in Council International, “Re: Joint Statement on Arctic Council Cooperation following Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine,” GwichinCouncil.com, March 3, 2022, https://gwichincouncil.com/sites/default/files/2022%20March%203%20GCI%20Statement.pdf

[12] Ibid.

[13] Inuit Circumpolar Council, “Statement from the Inuit Circumpolar Council Concerning the Arctic Council,” InuitCircumpolar.com, March 7, 2022, https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/news/statement-from-the-inuit-circumpolar-council-concerning-the-arctic-council/#:~:text=We%20are%20concerned%20about%20the,a%201987%20speech%20in%20Murmansk.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON), NGO in Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations, Document No. 64, March 1, 2022.

[16] International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia, Statement of the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia, Polar Connection, March 11, 2022, https://polarconnection.org/international-committee-of-indigenous-peoples-of-russia/

[17] Ibid.

Appeal of the Indigenous Peoples to international organizations and missions of states at international organizations

On February 24, 2022, the Russian Federation launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. As a result of rocket attacks on Ukrainian settlements, thousands of civilians were killed – representatives of different ethnic groups and confessions, indigenous peoples, including hundreds of children.

Russian organizations of indigenous peoples: Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East (RAIPON) – https://raipon.info, interregional public organization Information and Educational Network of Indigenous Peoples Lyoravetlian – https://www.indigenous.ru, the Association of Finno-Ugric Peoples of the Russian Federation – https://afunrf.ru, officially supported the criminal actions of President Putin to unleash a war against Ukraine.

We appeal to the United Nations, in particular the President of ECOSOC, to deprive the organizations that supported Russia’s aggression against Ukraine of their consultative status with the UN ECOSOC. And also prevent the appointment of representatives of these organizations to UN subsidiary organs, such as the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues and the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

We appeal to all international organizations that proclaim human life and freedom as the highest value, not to allow participation in their work of representatives of organizations of indigenous peoples of Russia that support Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine.

We believe that organizations whose representatives support the war and, accordingly, the killing of civilians in Ukraine, including the killing of representatives of indigenous peoples, cannot represent the interests and rights of indigenous peoples at the international level.

We appeal to the international community with a request to establish an independent commission to study and prepare a report on the impact of the military aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine on the indigenous peoples of Russia and Ukraine.

Signatures:

- Dordzho Dugarov, Buryat Democratic Movement

- Pavel Sulyandziga, Udege, International Fund for Development and Solidarity of Indigenous Peoples Batani

- Tian Zaochnaya, Itelmen, International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia

- Dmitry Berezhkov, Kamchadal, information center “Indigenous Russia”

- Erentzen Doolyan, Congress of the Oirat-Kalmyk people

- Eskender Bariiev, Crimean Tatar Resource Center

- Liudmyla Korotkykh, Crimean Tatar Youth Center

- Zarema Bariieva, Committee for the Protection of the Rights of the Crimean Tatar People

- Olena Arabadzhi, Head of the National-Cultural Karaite Society Dzhamaat

- Andrey Danilov, Saami, International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia

- Yana Tannagasheva, Shor, International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia

- Vladislav Tannagashev, Shor, International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia

- Irina Shafrannik, Selkup, International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia

- Vladimir Dovdanov, Deputy Chairman of the Congress of the Oirat-Kalmyk People

- Nikita Andreev, Sakha Democratic Movement

- Saglara Khartskhaeva, President of the Kalmyk Association of Spain and Portugal

- Galina Angarova, Buryat people

Statement of the Indigenous Peoples in connection with the full-scale military aggression of Russia against Ukraine

On February 20, 2014, the Russian Federation invaded Ukraine, as a result of which the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol, the birthplace of the indigenous Crimean Tatar, Karaite and Krymchak peoples, were occupied, as well as certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

On February 24, 2022, the Russian Federation launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. As a result of rocket attacks on Ukrainian settlements, thousands of civilians were killed – representatives of different ethnic groups and confessions, including hundreds of children.

Representatives of the indigenous peoples of Ukraine are dying under bombs, rockets and bullets from the Russian military. Representatives of the indigenous peoples of Russia and the occupied territories of Ukraine are dying in this war, forced to sign contracts with the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, as they were thrown into poverty by Putin’s regime.

We, representatives of the indigenous peoples of Ukraine and Russia:

– express support to the Ukrainian people in the fight against Russian aggression;

condemn;

– the barbaric and unprovoked war unleashed by Putin’s regime against the peoples of independent Ukraine,

– persecution and repression against the indigenous peoples, both on the territory of Russia and on the territories of Ukraine occupied by the Russian Federation;

– russian organizations of indigenous peoples that have publicly supported Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine and its indigenous peoples;

– pay special attention to the violation of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, in particular Art. 30, which prohibits any military activity on the lands of indigenous peoples without their free, prior, and informed consent, including the conscription of representatives of the indigenous peoples of Russia and Ukraine into the ranks of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation;

– call for the creation of an independent international commission to study and prepare a report on the impact of the armed aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine on the indigenous peoples of Russia and Ukraine;

recommend

– the Human Rights Council to establish the mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of indigenous peoples in situations of interstate conflict;

– include the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in the list of standards of the Universal Periodic Review of the Human Rights Council;

– develop a UN humanitarian response plan to protect the rights of indigenous peoples affected by Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine.

Signatures:

- Dordzho Dugarov, Buryat Democratic Movement

- Pavel Sulyandziga, International Fund for Development and Solidarity of Indigenous Peoples Batani

- Tian Zaochnaya, Itelmen, International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia

- Dmitry Berezhkov, Information portal Russia of Indigenous Peoples

- Erentzen Doolyan, Congress of the Oirat-Kalmyk people

- Eskender Bariiev, Crimean Tatar Resource Center

- Liudmyla Korotkykh, Crimean Tatar Youth Center

- Zarema Bariieva, Committee for the Protection of the Rights of the Crimean Tatar People

- Olena Arabadzhi, Head of the National-Cultural Karaite Society Dzhamaat

- Andrey Danilov, Saami, International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia

- Yana Tannagasheva, Shor, International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia

- Vladislav Tannagashev, Shor, International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia

- Irina Shafrannik, Selkup, International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia

- Vladimir Dovdanov, Deputy Chairman of the Congress of the Oirat-Kalmyk People

- Nikita Andreev, Sakha democratic movement

- Galina Angarova, Buryat people

For Russia’s Exiled Ethnic Activists, Ukraine War a ‘Window of Opportunity’

As the death toll from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine rises, throwing Kremlin imperialism into sharper focus, activists representing the indigenous non-Slavic peoples of Russia are doubling down on efforts to rally supporters behind demands for greater autonomy.

“War is a trigger for greater national consciousness,” Ruslan Gabbasov, the head of the Bashkir National Political Center, told The Moscow Times.

A disproportionate share of the Russian soldiers killed in Ukraine have come from the country’s minority ethnic communities, many of which are already blighted by poverty and targeted by official discrimination.

As the conflict drags on, ethnic activists hope that the colonialist overtones of Russia’s brutal invasion, which has also seen economic appropriation of Ukrainian resources and summary killings of unarmed men, could fuel discontent among non-Slavic groups – and even provide the political momentum to change the current structure of the Russian Federation.

“There will be a window of opportunity, and we will use it to get maximum rights and freedoms for our republic of Bashkortostan. We will try to become a sovereign state equal to others in the global arena,” said the Lithuania-based Gabbasov, who fled Russia in 2020.

Rafis Kashapov, a veteran Tatar rights activist and co-founder of the Free Idel-Ural movement that seeks independence and integration for a group of ethnic regions in central Russia, echoed Gabbasov’s comments.

“We believe that the Russian invasion of Ukraine will bring about the fall of the empire,” he told The Moscow Times in a telephone interview.

Ethnic activists from Russia, including Kashapov and Gabbasov, gathered earlier this month at the Free Nations of Russia Forum in the Polish capital Warsaw to discuss how the Ukraine war has impacted their communities, and what they can do to obtain more autonomy.

Forum participant Pavel Sulyandziga told The Moscow Times that Russia’s future is being “actively discussed” among communities such as Buryats, Sakha and Kalmyks.

However, he was cautious about the prospect of an imminent collapse of the Russian Federation — which, in its current form, grants some non-Russian groups a degree of independence in so-called “ethnic homeland regions.”

“Minor indigenous peoples do not have the necessary preconditions for self-determination, and we will be forced to remain minorities no matter where we live,” said Sulyandziga, who heads the Batani fund for indigenous peoples in Russia.

Different ethnic groups in Russia do not have a common position on what political changes they would like to see, with aspirations varying according to size, history and outlook. For example, the political options for Bashkortostan – Russia’s most populous, resource-rich ethnic republic located between the Volga River and the Ural mountains – are very different to those of tiny ethnic groups that may number just a few hundred people.

Activist Gabbasov suggested Ukraine could be a political model for the Bashkirs.

“Our project is one of a political nation like in Ukraine, where a Jewish president is leading the state and ethnic Georgians, Chechens, Crimean Tatars are fighting alongside [ethnic] Ukrainians and all equally consider Ukraine their motherland,” he said.

For many ethnic groups, the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine has reminded them of Russia’s imperial conquest of their homelands and recent policies of “Russification,” including the exclusion of minority languages and local history from school curriculums.

Perhaps the most stark illustration of the unequal relationship between indigenous groups and ethnic Russians has been the record numbers of Russian soldiers from non-Slavic ethnicities killed in Ukraine.

With 143 killed soldiers, the North Caucasus republic of Dagestan tops a ranking of regional deaths compiled from open sources by independent media outlet iStories. In second place is the Siberian republic of Buryatia with 113 confirmed deaths. Just a handful of soldiers from large cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg have been reported killed in Ukraine.

Russia has not published official figures on the ethnic make-up of its military losses in Ukraine, and has not updated its overall death toll since March.

“An open linguicide and ethnocide [has been] happening. Today, genocide has been added to this both in relation to the Ukrainian people and in relation to indiginous peoples of Russia whose representatives are sent to the war for slaughter,” Gabbasov told the Warsaw conference, media outlet Idel.Realii, a regional affiliate of the U.S.-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, reported.

While it is hard to gauge the exact level of support on the ground for greater independence from Moscow among Russia’s non-Slavic peoples, there is evidence of growing interest in learning about national languages and histories.

“I’m so ashamed that before the war I knew nothing about the culture that I was brought up in and that is native to me. I never really spoke the native tongue,” a participant wrote earlier this month in a closed chat on the Telegram messaging app seen by The Moscow Times.

Fear means many people are reluctant to express dissent, according to activists.

“People are very scared,” Sulyandziga said when asked about the mood among the communities in Russia’s Far East and Siberia.

“We receive a lot of messages saying that many people in indigenous communities, particularly mothers whose children have been sent to the war, are speaking out… [But] unfortunately, most of those whose family members have not been sent to the war choose to stay silent or support this victory-mongering,” he said in a telephone interview from the United States, where he received asylum in 2017.

Russia’s ethnic minority rights advocates have operated under the threat of “extremism” charges since the early 2000s, and most currently live abroad.

“I can’t say my activities have become limited [since fleeing Russia]. On the contrary, I can do more… because I feel free and finally able to say what I think,” said Gabbasov.

Sulyandziga said that although being in exile limits what he can do, he remains hopeful.

“I keep doing my work because our [indiginous] peoples reach out to me on a daily basis. Their rights are violated, and they cannot find justice,” he said.

“History teaches us that, sooner or later, all empires fall or transform.”

These Indigenous activists stood up for their rights and were forced to flee Russia

Pavel Sulyandziga and Yana Tannagasheva are part of a new group that is working for a safer Russia for Indigenous peoples

Pavel Sulyandziga fled Russia in 2016, seeking political asylum. His family was in danger — all because of his work as an Indigenous activist.

He had been investigated by the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) multiple times. He was called a separatist and extremist. His friends and colleagues were questioned about him. The authorities even knew about conversations in his own home — at one point, he was contacted and asked, “Why are you talking politics with your wife?”

“The biggest threat was to my son, who was in the army,” Sulyandziga says. “….A commander called me and said that the FSB decided to send him to a hotspot, the Southern Military District, in the North Caucasus region of Russia.” This region is especially fraught with conflict, and Sulyandziga knew his son was being punished because of Sulyandziga’s actions.

Sulyandziga is from the Udege nation, an Indigenous group of about 1,700 people. Most of the Udege population lives in the Primorsky Krai and Khabarovsk regions in Russia’s far east.

Many Indigenous groups in Russia are part of established republics, which offer some form of state representation. But for smaller, more remote communities, the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) acts as the defender of their rights and interests. RAIPON represents 42 Indigenous groups, seven of which have fewer than 1,000 members.

In 2001, Sulyandziga was elected as a first vice-president of the organization, which is internationally recognized and a permanent participant in the Arctic Council. But he now says that RAIPON is no longer a legitimate, independent one that represents Indigenous interests.

“RAIPON is now a pawn for the government, used to shut down activism and independent leaders who want to do things democratically,” he says.

On March 1, RAIPON announced that they “unanimously supported” Putin’s war in Ukraine.

Fuelled in part by that move, Sulyandziga formed a new organization with six others called the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (ICIPR).

“All of these people are political refugees now, they’ve all been forced to leave the country because of their views,” he says.

ICIPR aims to be a voice for those who can’t speak freely about the challenges that Indigenous peoples face in Russia. This includes environmental protection and safety for Indigenous people and activists, among other things. Sulyandziga says these are challenges that RAIPON would prefer to ignore in order to protect Russia’s image.

The trouble with RAIPON began in 2012, when Russia’s Ministry of Justice shut it down for six months, citing illegal activities. When it reopened in 2013, some important changes had been made. While previously, the delegates were elected democratically by each Indigenous group, now they were chosen for these communities from a pre-approved list.

In international settings, like the United Nations, Sulyandziga says “the FSB representative present at the UN meeting gives people who work for RAIPON a list of things that they have to say, [and tells them] when and how to say them.”

Around this time, the threats against Sulyandziga began. He wasn’t staying quiet about what he thought were important challenges that Indigenous peoples were facing in Russia — and in December 2013, he was ousted from RAIPON because of it. He continued to speak out despite this.

When Sulyandziga would visit his son at the army base where he was stationed, the FSB would confiscate his son’s passport so that he would be unable to leave. “The six months my son was in the North Caucasus were among the most difficult in my life and I was extremely scared,” he remembers.

After collaborating with a commander in the army and mailing his phone to a friend so that he couldn’t be tracked, Sulyandziga was able to sneak his son out of the area in the middle of the night.

His family left Russia in 2015, and Sulyandziga followed in 2016. Today they live in Maine, where Sulyandziga works as the founder and president of the International Indigenous Fund for Development and Solidarity (Batani). Batani began in Russia in 2004, but was liquidated by the state in 2017 after being labelled a “foreign agent” (a common strategy used by Russia to eliminate NGOs and silence activists). Today, Batani works toward implementing community development programs in Indigenous communities and fighting for Indigenous rights worldwide.

“Everyone who is part of the opposition in Russia and activists all experience the same [thing],” he says. “And obviously, they don’t just threaten opposition leaders, it goes as far as threatening the families of those people, not just the people involved.”

Yana Tannagasheva is another member of ICIPR. She now lives in Sweden, after fleeing with her family in 2018. She’s a member of the Shor — an Indigenous group in southwestern Siberia with a population of about 12,000. The majority of Shor live in Kemerovo Oblast, a federal subject of Russia also commonly known as Kuzbass.

Her activism began in 2013, when Yuzhnaya, a coal company mining near Kazas, Tannagasheva’s family village, tried to buy out the landowners who lived there. The coal mines near Kazas had already destroyed the forests and dirtied the water, making traditional practices like hunting and fishing nearly impossible. Her father and four other families refused to sell their homes.

“He got his house from his father, my grandfather,” she says. “And his father said, ‘in the future, please don’t sell our house.’ It is our village, our place.”

Those who refused to sell were threatened by the company. And then, between November 2013 and March 2014, all five remaining houses burned down. Even though the only way to enter the village was through a checkpoint with security cameras, nobody was ever charged.

Now, residents are not even allowed access to the cemetery where their ancestors are buried. These graves are all that is left of Kazas.

Tannagasheva tried every avenue available to her to protect the rights of her people: local representatives like mayors and governors — and RAIPON, the organization that is supposed to work on these very issues.

“The president of RAIPON, Grigory Ledkov, went to the region, to Kuzbass. But instead of meeting with the families, especially the elderly people, who suffered and saw their homes being burned down…they only went to the people who would confirm that everything is okay,” Tannagasheva says. “They just had no interest in talking to the actual survivors.”

In a 2018 document submitted to the United Nations, Russia says that the residents of Kazas were resettled and are “wholly satisfied” with their new village. It claims that the decision to suspend the criminal investigation into the acts of arson were based in law. Lastly, it states that Kazas is fully accessible to visitors, including the cemetery.

“After 2017, it was worse and there were a lot of threats to my children,” Tannagasheva says. “After one year we decided to flee. And two years ago, Sweden gave us status here … but we cannot visit our country, visit Russia.”

“[Those] who are now in Russia, they tend not to have a big, good voice [for] Indigenous Peoples — it’s so, so dangerous to speak about [the] war [in Ukraine] there. And they said to us, ‘We want Indigenous peoples to speak about it, but only you who are now abroad and in another country can speak about it loud,’” she says.

Sulyandziga, Tannagasheva, and the five other members of their group are working towards a safer Russia for Indigenous peoples and a strategy for the future, one where they have a voice in their own country.

As Sulyandziga says, “We think we can use our voice to express how people who are being silenced feel [in Russia].”

Emily Standfield is a writer in Toronto.

Russian translation provided by Albina Retyunskikh

Indigenous Siberians, barred from fighting fossil fuels back home, join Line 5 fight

In the United States and Canada, Native citizens can point to long-held treaty rights as attempted recourse against encroaching fossil fuel projects. Such is the case with the Great Lakes tribes that oppose Canadian company Enbridge’s Line 5 pipeline in Michigan and Line 3 in Minnesota.

However, there is no such recourse available for Indigenous people of Siberia, who face similar challenges many thousands of miles away.

“If [this] happened in Russia, I know that we would go just directly to jail,” said Stanislav (Saas) Ksenofontov, gesturing to the large gathering of tribal citizens who were gathered in northern Michigan on Saturday to protest Line 5.

Water protectors and supporters, Ksenofontov among them, had just marched several miles through the streets of Mackinaw City to arrive at Conkling Park near the waters of the Straits. Speakers from Michigan, Canada and beyond spoke about the dangers of fossil fuels and the importance of protecting the earth from companies that value profit over life.

That kind of public Indigenous resistance against extractive industries “is not possible” in Russia, Ksenofontov told the Advance. “… I see this, and I’m just amazed.”

Extractive industries disproportionately harm Indigenous lands, and Native peoples are often among the first to experience the effects of climate change. Oil pipelines in Russia, including the Druzhba pipeline that is the world’s longest, are expansive and crisscross many Indigenous territories.

Russia’s Indigenous peoples inhabit roughly two-thirds of the country’s territory, yet very few have any land or treaty rights. Those that do are provided with very limited benefits.

The ability to protest is also severely limited in Russia, something that’s in the international spotlight as the authoritarian government is cracking down on demonstrators opposing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“I was thinking today, walking from the church to this square … [In Russia,] there is a law banning to gather more than five people. So we cannot protest, we cannot march. It’s not allowed.

“It’s not allowed to criticize government. We will be just jailed,” Ksenofontov said.

Ksenofontov was one of several Indigenous Siberians to speak and perform at the Heart of the Turtle gathering over the weekend. The Michigan-based water protector group MackinawOde organized the events to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the state’s attempted Line 5 “eviction.”

Enbridge has been considered an international trespasser in the Straits by the state of Michigan since May 13, 2021. Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer had ordered months before that the company cease oil transport through Line 5 by that date; instead, Enbridge refused and filed a federal lawsuit to challenge the state’s ability to shut down the pipeline.

That lawsuit remains pending as a federal judge deliberates.

“All these companies should just leave the sacred lands, shouldn’t destroy ecosystems and traditional practices,” Ksenofontov said of Enbridge. “Fortunately, people resist here, people protest, it’s really amazing. Unfortunately, we cannot do that in our situation because it’s dangerous, it’s prohibited.”

Tribal citizens involved in organizing the event in protest of Line 5 first linked up with the Indigenous Siberians in March, where water protectors across the globe converged for an international conference at the University of Minnesota Duluth to speak about resisting pipeline development in Indigenous lands.

Ksenofontov, an Indigenous social scientist from the Sakha Republic (Yakutia) in northeast Siberia, is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Northern Iowa. He has previously studied in Switzerland and Korea.

Sakha is the largest of Russia’s 85 federal subjects and stretches more than one million square miles. The region is rich in minerals like diamond, gold and coal.

Only 40 of Russia’s 160 distinct peoples are officially recognized by the government as Indigenous, as Russia dictates that they must be composed of less than 50,000 members.

“Since my nation is … more than 50,000, we are not ‘Indigenous’ and we are not recognized by the government. So we have no rights to land, we have limited rights to hunting and fishing,” Ksenofontov said.

This makes recourse for his people “quite difficult” when faced with issues like deforestation, oil projects and more, he said. A recent struggle in Sakha involves two Russian logging companies that want to take trees from Indigenous land and export them to China.

“These forests are located in a really pristine place, the cleanest river and the endangered animals. It will just be gone if they start to cut trees,” Ksenofontov said.

“[The Russian government] … they just steal resources, they just steal money from the people and they never share benefits on the resources. Our region is the richest in Russia. We have gold, oil, gas, diamonds, silver, everything. … Every single element is in our region, and we don’t receive anything. We receive just super small amount of benefits from all these resources,” he continued.

“They are just filling up their pockets.”

Pavel Sulyandziga, an elder of the Udege people in southeast Siberia and one of Russia’s most outspoken Indigenous rights activists, has been deeply involved in the struggle against extractive businesses since the 1980s.

“The government of the Russian federation and president [Vladimir Putin], they do not respect Indigenous peoples’ rights,” Sulyandziga said in his native language on Saturday, as translated by University of Northern Iowa professor Andrey Petrov.

The Udege people are natives of the Primorsky Krai and Khabarovsk Krai regions in Russia. Since the 1980s’ “Perestroika” movement for reform within the Soviet Union’s Communist Party, Sulyandziga has been a leader for his peoples’ struggle over traditional Udege territories along the Bikin River.

Those struggles include attempts to fend off deforestation, government-backed jade mining, and projects from oil companies like Shell, Mobil and Exxon.

“The companies would come. They would destroy the environment and that would have an impact on the Indigenous peoples’ livelihoods,” Sulyandziga said.

Sulyandziga currently chairs the Board of the International Development Fund of Indigenous Peoples in Russia (BATANI). Amid many other prestigious posts related to Indigenous peoples in Siberia, he was also a member of the United Nations (UN) Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues from 2005 to 2010 and a member/chair of the U.N. Working Group on Business and Human Rights from 2011 to 2018.

In 2017, Sulyandziga visited the Indigenous-led resistance at Standing Rock, N.D., in an unofficial capacity. Activists faced off against law enforcement there to protest against the now-operational Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL).

He said he came to northern Michigan to stand with water protectors against Line 5 and Line 3 over the weekend “to support Indigenous peoples here to fight against the pipeline.”

Sulyandziga faced backlash from the powers that be in Russia for his public fight against businesses threatening Native lands. Fearing potential persecution, he applied for political asylum in the United States in 2017.

“Russia, the Indigenous peoples rights are completely unfollowed, violated, totally violated. They are broken,” Sulyandziga said.

He now resides in Maine as he continues to await asylum status. Sylyandziga says many other tribal leaders from Russia who do similar activism now live in different countries as they, too, seek asylum.

Other Indigenous Siberian speakers at the Heart of the Turtle Gathering included Lena Popova, Tatiana Degai, Varvara Korkina Williams and Viktoria Sharakhmatova.

MackinawOde founder Nathan Wright, a citizen of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, said all of the Siberians present at the Line 5 gathering will be returning to northern Michigan in July.

The Siberians will meet then with the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians (LTBB) for a youth-centered gathering to exchange Indigenous knowledge.

“We will share our teachings and they will share theirs,” Wright said Tuesday.

All 12 federally recognized tribes in Michigan publicly oppose the Line 5 pipeline and its proposed tunnel-enclosed replacement.

Russians in Maine find relations strained with friends and family overseas

Disinformation about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has convinced many in Russia to support the regime’s unprovoked war.

YARMOUTH — Pavel Sulyandziga’s former classmates at Khabarovsk State Pedagogical University in Russia’s Far East used to engage in friendly chats about family, gardening and career developments on their WhatsApp group.

Within a week of Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, the Yarmouth resident said the tone changed. A classmate – a doctor of mathematics and physics – started posting praise of Russian troops for what she believed was their heroic effort to save the Ukrainian people from Nazis. Another posted images of the “Z” painted on many Russian military vehicles involved in the brutal invasion, which has become a symbol of support for Vladimir Putin’s war.

When Sulyandziga, an Udege indigenous activist and dissident and asylum recipient who has lived in Maine since fleeing retribution by Putin’s regime in 2015, pushed back, things quickly got ugly.

“I said, what do you mean they are liberating the Ukrainians? None of them are for you, they are all fighting against you,” he recalled. “She wrote back that Putin knows everything, and he is our leader. I was told I was a fascist and a Banderite,” a supporter of the World War II-era Ukrainian nationalist and Nazi collaborator Stepan Bandera, who was assassinated by the KGB in Munich in 1959 and whose name has become the Putin regime’s go-to slur for anyone supporting Ukrainian sovereignty.

“I finally just left the group,” Sulyandziga said. “It doesn’t exist for me now.”

Over the past six weeks, Mainers who immigrated from the Russian Federation have been having exasperating interactions with many of their friends, colleagues and family members back at home who live inside the regime’s disinformation bubble. That’s where up is down, two and two make five, there is no war in Ukraine and Russia’s flawless leader is responsible for saving Ukraine’s people from fascism, rather than destroying their cities, driving 10 million from their homes, and killing an estimated 1,200 civilians in an unprovoked invasion condemned by almost the entire world.

The propaganda bubble is highly effective and driven by Putin’s total control over Russia’s television stations, the closure of the last independent newspapers and radio stations, the blocking of many foreign broadcast and digital news sources and a draconian crackdown against protesters and dissent.

“One of the main reasons it is so effective is because people are already preconditioned to believe these kinds of stories, and not just because the propaganda has been saying these kinds of things for years,” said Anton Shirikov, a doctoral student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who researches Russia’s domestic propaganda. “A lot of people in Russia were and are very upset about how the Soviet Union collapsed, and the reoccurring narrative is that this is all the West’s fault along with the CIA and the traitors who negotiated the collapse. The Ukraine war is just a continuation of that story: Ukraine and NATO plotting against Russia.”

Even people who might be inclined to question the propaganda narrative about the war have incentives not to, Shirikov said. “It would require them to admit that they were lied to for many years and that they were gullible and deceived. It’s not pleasant to admit these things, and when you don’t hear any dissenting voices around you and everyone is saying, ‘This is a just war,’ it’s even harder to start questioning.”

MAY NEVER GO BACK TO HER VILLAGE

Svetlana Bell emigrated to Maine in 1995 from Krasny Yar, a village in the Primorsky of the Russian Far East, 40 miles east of the Chinese border, where most inhabitants are ethnic Udege or Nanai like herself. But she’s found Moscow’s propaganda – which features Russian ethno-nationalism – is highly effective, even from 5,300 miles away in a community with few ethnic Russians that’s closer to Japan.

“I have two sisters there, and they really don’t know there’s a war going on, which for me was a big shock,” Bell said. “They watch television every day, and they don’t talk about the war in Ukraine on the TV news.”

Bell, who is married to former Press Herald reporter Tom Bell and lives in Yarmouth, said she tried to explain to one sister what was really happening in Ukraine. “She didn’t believe me and was very angry at me for telling her this because she said Russia supports peace around the world. They are taken in by the propaganda, and the phone calls became really tense because of the disagreement over what was happening.

“I don’t want to call them or argue with them anymore,” she said.

There are dissenters. A man Bell knew in Krasny Yar, whose wife was in Ukraine, saw a photograph Bell posted on social media of her attending an anti-war protest in Portland and contacted her via WhatsApp. “He was so glad to learn that I was protesting the war, and he had found a way to learn what was going on there,” Bell recalled. “I don’t know how he was able to get the information, but for most people it is very difficult.”

Later she saw a photograph on social media she found devastating. Villagers had gathered in traditional indigenous clothing and used a drone to take a picture of themselves standing in a “Z” formation around a Russian flag. “I was very disgraced to see that,” she said. “Maybe after this, I will never be able to go back to this village.”

Several Russian immigrants declined to speak to the Press Herald for fear of getting their family members in trouble or because it was too painful to do so. One couple from Russia’s North Ossetia region in the Caucasus Mountains who live in Greater Portland agreed to speak anonymously about their communications with friends in larger cities there.

“Our relatives are very smart and intelligent people who never bought anything they saw on TV, so it’s easy to talk to them because they see things as we do,” the wife in the couple explained, noting YouTube and some other platforms still function in Russia, allowing people who want to seek out information from the outside to do so. “But they say when they try to explain to the people around them what is going on, to convince them that everything they see on (Russian regime-controlled) TV has nothing to do with reality, it’s like talking to a brick wall.”

Her husband has tried talking with his former high school classmates, but he gets too frustrated to continue. “They just respond with the slogans they see on TV, with exactly the same words, like they’re reading from a script,” he said. “I know I can’t make a big hole in that wall, but just a little hole would be nice.”

They say younger people in larger cities are generally not taken in by the propaganda because they don’t watch television. “They go into TikTok and Instagram and Facebook so they don’t buy it,” the wife said. “But people who live in small towns and villages don’t have access to the internet or, if they do, often don’t know how to use it. So their only access is via television and radio, and that puts them so far from the reality of the war.”

‘THEY WATCH ONLY RUSSIAN NEWS’

Victoria Liashenko emigrated from Russia six years ago and lives in Portland with her American husband. Her parents live in Tatarstan, about 600 miles east of Moscow, and even though her father’s family are ethnic Ukrainians, when it comes to the war they’re living, as she puts it, in “an illusion.”

“They watch only Russian news, which tells them that nothing is happening and that they need to trust the government,” she said. “There has been some arguing between us. They don’t understand why they should have to fight for freedom; they just want to leave things as they are. They are used to this world.”

Her parents also fear Putin’s regime. “I posted something on Instagram against the war, and my mom called me crying worried that the KGB will show up at the house,” Liashenko, who participated in the first protest of her life in Boston last month, recalled. “I told her that’s not true, but they are so scared.” They’ve never met her husband, and she wonders when they ever will.

None of the Russians the Press Herald spoke to for this story had any hope that their countrymen would rise up to overthrow Putin because a large majority accept and support his nationalist agenda, tacitly or actively.

“There’s a minority of people who don’t like Putin’s regime, but most of the people who could have risen up already left Russia,” Sulyandziga said. “I don’t think anything major is going to happen. The only possibility is a palace coup.”

Staff writer Eric Russell contributed to this story.

Аn appeal of the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia to representatives of indigenous peoples in the Russian armed forces

#StayAtHome

We, representatives of the indigenous peoples of Russia, appeal to indigenous persons who serve in the Russian armed forces with a request not to take part in the shameful war in Ukraine that president Putin calls a “special military operation”.

It is well known that the indigenous territories of Russia, where indigenous peoples live, rank last among Russian regions in terms of quality of life, even though these lands are the source of natural resources that support the whole Russian economy.

A majority of Russia’s indigenous municipalities and ethnic republics are economically backward regions with poor populations because most of the wealth produced by these regions goes to Moscow. This money President Putin uses for implementing his imperial plans to suppress the freedom of the peoples of Russia and other countries.

The imperial chauvinism cherished by Vladimir Putin for 20 years drives you today as members of the Russian armed forces to the bloodbath in Ukraine to implement his order to crush the will of the Ukrainian people to freedom.

But only freedom makes it possible for every nation to possess their traditional lands fruitfully, preserve and develop their languages, cultures, and traditions, and be equal among other civilized peoples. Today Ukrainians show everyone how to love their native land, people, and way of life. Today, they are defending their own freedom and the freedom of the peoples of Russia, and our fate is now being decided in Ukraine.

Solders and representatives of indigenous peoples in the Russian armed forces! Today you have the opportunity to save your lives, the future of your nations, and the lives of thousands of innocent people in Ukraine. You need to stop your participation in military actions. Do not allow your commanders to send you or your colleagues to the war in Ukraine. Sabotage the orders of your superiors who demand to shoot Ukrainians and destroy Ukrainian cities.

Authorities are frightening you by punishment and prison for refusing to go to the war. But if you do not go, you won’t be killed. You will stay alive! There are already examples of refusals by militaries of the Federal National Guard Troops Service who refused to cross the border of Ukraine because this is an illegal action according to the law of the Russian Federation. Their commanders illegally dismissed them from service. That is how they suffered for not going to the war, but they returned home alive.

You don’t need to die for the palaces, yachts, and billions of Putin and his friends. You can not kill Ukrainian civilians – children, women and the elderly. Each of us has to stay a human being.

Your families and loved ones are waiting for you at home as their destiny depends on your decision.

The war is a crime!

You have to make a choice!

Please stay home and say NO to the war!

International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia

Congress of the Oirat-Kalmyk People

Buryat Democratic Movement

National Movement of the Northerners

Statement of the Association of Finno-Ugric Peoples of the Russian Federation on the support of the Russian president Vladimir Putin

STATEMENT

of the All-Russian Public Movement

“Association of Finno-Ugric Peoples of the Russian Federation”.

We, the representatives of Finno-Ugric peoples of Russia, express our support to the President of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin, who has decided to protect the rights and interests of the inhabitants of Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republic and arranged forced and necessary measures to strengthen the security of our country.

We believe that the revival and spread of Nazi ideology, a manifestation of any forms of discrimination on linguistic, national and religious grounds, are absolutely unacceptable in the present-day world.

Our compatriots, relatives and loved ones live beyond the Russian-Ukrainian border, and they became hostages of the policy aimed at inciting hate and hostility in society.

We express our solidarity with the Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic residents and other peaceful residents of Ukraine and hope for the soonest establishment of peace and mutual understanding.