Cracking the corporate code

Serving on a corporate board is a good gig – and Indigenous people are missing

Mary Smith had a plan: She was going to serve as a member of a corporate board. She already had the resume. Smith is an attorney and she had worked as the chief executive officer for the U.S. Indian Health Service, a $6 billion-a-year-operation.

“I think for most people, you’re not going to get a call out of the blue,” she said. “You have to put yourself out there so that people know that you want to be on a corporate board because there are recruiters that recruit for corporate boards. But, the vast majority of board seats are still filled through networking.”

Smith’s planning was deliberate. She “very intentionally treated it like a full-time job.” That included learning about corporate governance and board responsibilities, she developed a “board bio” which she says is different from a resume because it highlights attributes that boards are looking for (such as experience with regulatory agencies.) She also hired coaches in order to sharpen her pitch.

“I really wanted to try to get on a board and I didn’t want to look back and say, ‘Oh, I wish I had done X, Y or Z. ‘ If I had done that, I would’ve made it so.”

Smith has made a place for herself at a table where few Indigenous people have historically been invited.

There are some 4,000 companies traded on Wall Street through the New York Stock Exchange or NASDAQ. Each of these companies have professional board members who are responsible for corporate governance. The number of American Indians and Alaska Natives represented on those boards is far less than one-tenth of one percent.

Smith, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, now serves on the board for PTC Therapeutics, Inc., a publicly-traded global biopharmaceutical company that focuses on “ the discovery, development and commercialization of clinically differentiated medicines that provide benefits to patients with rare disorders.”

She is paid a board fee of $30,659, according to the company’s report with the Securities and Exchange Commission, on top of that she is awarded both options and stocks that depend on the success of the company and could be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Smith says there is more to serving on a board than showing up to four meetings a year. “That sounds like an easy gig, but, no, it’s actually a lot of work,” she said. There are documents that must be reviewed, a duty of care and loyalty, one poor decision could result in liability.

“So, yes, you have to be very thoughtful and exercise your fiduciary duties to the corporation.”

According to the search firm Spencer Stuart and its annual report index the total average compensation for a board seat is $312,279. “This average reflects actual director compensation, including the voluntary, and usually temporary, pay cuts some boards took during the height of the pandemic crisis. More than three-quarters of boards provide stock grants to directors in addition to a fee.

Serving on a corporate board is a good gig. And the number of Indigenous people who hold board seats is too small to register; far less than one-tenth of 1 percent.

There are a few prominent Indigenous board members. Cherie Brandt serves on the board of TD Bank in Toronto. She is both Mohawk from Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte and Ojibway from Wiikwemkoong Unceded Indian Reserve. She was appointed last August. Kathy Hannan, Ho Chunk, serves on Otis Elevator and Annaly Capital Management.

There are also a number of Indigenous people serving on regional bank boards, utility companies, across the energy sector.

Across the board the data shows movement. The 2021 U.S. Spencer Stuart Board Index shows that white directors fell slightly in 2021, yet still account for eight of every 10 board members, and six of the 10 are white men. (Spencer Stuart is a firm that conducts corporate searches.)

The index also found that directors from historically underrepresented groups accounted for 72 percent of all new directors at S&P 500 companies, up from 59 percent in 2020. Female representation increased to 30 percent of all S&P 500 directors.

“Despite the record number of new directors from historically underrepresented groups, the overall representation of some demographic groups on S&P 500 boards falls short of their representation in the U.S. population,” Spencer Stuart reported. “For example, although 42 percent of the U.S. population identifies as African American, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian/Native Alaskan or multiracial, those groups make up only 21 percent of S&P 500 directors.”

The 6th edition of the Missing Pieces Report: The Board Diversity Census by the accounting firm Deloitte and the Alliance for Board Diversity is a multiyear study that found that public companies are making slow progress appointing more diverse boards. The goal of the Alliance is to have women and minorities make up 40 percent of all corporate board seats, up from 17.5 percent in 2021.

And the thing is, the Alliance for Board Diversity says based on the skill set of new board members, “women and minority board members currently are more likely than White men to bring experience with corporate sustainability and socially responsible investing, government, sales and marketing, and technology in the workplace to their boards.”

In other words: if the new framework is sustainability, especially Environment, Social, Governance, or ESG, then people of color who are appointed to board members are more likely to be prepared for the task ahead.

Native Americans are largely absent from corporate leadership.

The numbers are striking. According to Deloitte, less than one-tenth of one percent of all corporate board members are in the “other” category. There are so few Indigenous people in corporate boardrooms that there is not even a measurement. (The Spencer Stuart Board Index simply reports less than one percent for American Indian and Alaska Native representation.)

There are a couple of initiatives trying to change that. The first comes from the National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations, or NASDAQ, a computerized system for trading stock. In August of 2021 a Board Diversity Rule was established that requires companies to use a standard template for board representation and “have or explain why they do not have at least two diverse directors.”

And in California a 2020 law requires companies headquartered in that state to have one to three board members who self-identify as a member of an “underrepresented community,” which includes Asian, Black, Latino, Native American, and Pacific Islander individuals, as well as those who are gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender. The law allowed the Secretary of State to fine companies who did not comply. Then in May of 2022 a Los Angeles court struck down the law as unconstitutional and its application is on hold until the appeal process is complete.

But companies are acting anyway. Four years ago nearly one-third of public company boards in California were composed of all men. According to the most recent report from the California Partners Project, today fewer than 2 percent are. This year two-thirds of California public companies have three or more women directors—six times as many as in 2018.

“I think it’s very important to have representation, especially from the Native American community,” said Assemblyman James Ramos, D-San Bernardino. Ramos is a citizen of the Serrano/Cahuilla tribe, and is the first California Indian to be elected to the California State Assembly. “It serves two different folds, one to make sure that representation of not only California’s first people, but that the nation’s first people has a voice in driving the economics of our community, of our state, and of our nation.”

Ramos said it’s also aspirational, demonstrating opportunity.

“It definitely is right to make sure that Native American people are included in the overall discussion,” Ramos said. “When you’re putting statistics and data together, we hear it all the time: Latino, population, right? Statistics and data. African American, statistics and data. And yet we’re talking about people of color and diversity and not even mention Native American people or even California Indian people in general.”

There have been a significant number of Native Americans serving on philanthropic boards.

Sherry Salway Black, Oglala Lakota, has served on a number of such boards and she said she heard the narrative often that only one or two Native Americans served on private foundation boards. So she did a “quick and dirty” survey and found at least 28 Native people serving on 13 private foundations, and nine Native people on the boards of seven community foundations.

One area where there is a lot of Native board action is for Community Development Financial Institutions that are mission driven and focused on community building and access to capital. There are dozens of such lending institutions and it’s been especially important in the agriculture sector.

Carla Fredericks, Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara, is chief executive officer of The Christensen Fund, a $300 million foundation. She said it’s important to be intentional about how board members are appointed.

“This is long overdue,” she said. “Even as we’ve tried to get additional board members for our board, we are certainly aware that while there’s incredible leadership experience in Indian Country, and there’s not a lot of board experience that people have. So it’s really important to build that.”

Fredericks said it can be a self-perpetuating problem if boards require previous experience but don’t explore translatable experiences.

“We took a broader lens to looking at candidates,” Fredericks said. “I also think that we had a really intentional lens to recruit Indigenous people to the board. And that’s been a practice that’s been in place before I even got here. We’ve had Indigenous people on and off the board, Winona LaDuke, Rick Williams, others, throughout our history.”

Part of that means reshaping the debate about leadership.

“Many corporations now are adopting leadership structures that may be called something very fancy, but might have really strong roots in indigenous leadership,” she said. It’s the idea that there is a way to think about organizations and values that have not been previously considered.

“You kind of have to peel back the onion really, and try to understand, it’s not just who’s on the board, but who’s really engaged? And in what way, and what committee are they in charge of?” She said that’s all a part of the board governance piece and what will take for people to successfully lead and transform organizations.

ICT has been building a list of Indigenous representations on corporate boards, government-sponsored enterprises, university boards, and major nonprofits. The idea here is that there is a deep talent pool already available. When members of Congress, for example, retire or even lose an election, they are often sought after as corporate board members. That same process is not the same for tribal leaders who have been managing multimillion dollar enterprises, especially large tribes such as the Navajo Nation or the Cherokee Nation.

One part of that equation is how boards recruit new members. The report Missing Pieces, a 2021 census compiled by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sloan School of Management, said there is an immediate impact after placing women and minorities into key positions, such as on the nominating committee.

“When they have a woman or minority as their nominating or governance chair, boards are not immediately more likely to have higher percentages of women or minorities,” the report said. “After two years, these boards are more likely to have higher percentages of women or minorities.”

Mary Smith, the Cherokee Nation citizen on the PTC Therapeutics board, said there is a need to expand the network beyond former chief executives into other areas of experience, such as tribal leadership.

“I would love to see more Native Americans on boards. And I hope that some people would start to say, ‘yeah, I could do that.’ And then try to put themselves out there to be on the radar for people being on boards. Because I think people in the Native community have a lot to contribute to corporate boards.”

First Peoples Worldwide Joins Indigenous-led Coalition that Promotes Rights-Centered Transition to the Clean Energy Economy

SIRGE Coalition Launches Website August 9 to Help Secure Indigenous People’s Rights in a Green Economy

First Peoples Worldwide is among several organizations to provide leadership to a new coalition to Secure Indigenous People’s Rights in a Green Economy (SIRGE Coalition). To commemorate the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, the SIRGE Coalition will launch its website www.sirgecoalition.org on August 9.

Founded by Cultural Survival, Batani Foundation, Earthworks, the Society for Threatened Peoples, and First Peoples, the SIRGE Coalition works to ensure that the rights and self-determination of Indigenous Peoples are upheld in the just transition to a low-carbon economy.

The transition minerals necessary for new and renewable energy development, such as nickel, lithium, cobalt, and copper are found on Indigneous land throughout the globe. With demand for these minerals skyrocketing, “increased mining threatens Indigenous rights and territories where there is not a comprehensive assessment of risks and harms to Indigenous Peoples, and complete participation of Indigenous Peoples who are impacted,” the coalition said.

“We must center Indigenous Peoples’ and human rights as well as true, regenerative practices as we transition to the new green economy,” said Galina Angarova, Executive Director of Cultural Survival. “A meaningful, intentional, and truly Just Transition will require a set of solutions including improving existing standards, reforming old mining laws, mandating circular economy practices, setting standards and meeting targets for minerals’ reuse and recycling, reducing demand and accepting de-growth as a concept and a pathway, and most importantly, centering human rights and the right to the Free, Prior and Informed Consent in all decision-making.”

To promote constructive dialogue, SIRGE Coalition works with corporations, finance and government decision-makers to forward Indigenous rights in accordance with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and to “uphold all rights of Indigenous Peoples, including their cultures, spiritual traditions, histories, and especially their rights to determine their own priorities as to their lands, territories, and resources.”

“Partnership with Indigenous Peoples is integral to climate-resilient development,” said Kate R. Finn, Executive Director of First Peoples Worldwide. “The SIRGE Coalition provides pathways to concrete action necessary to protect Indigenous Peoples’ rights and reduce material loss for companies in the rising demand for renewable energy resources.”

Kenya: UN expert hails historic reparations ruling in favour of indigenous peoples

An independent UN human rights expert on Monday hailed a decision by the African Court on Human and People’s Rights, to award reparations to the Ogiek indigenous peoples, for harm that they suffered due to “injustices and discrimination.”

The historic ruling follows a landmark judgment delivered by the Court on 26 May 2017, finding that the Government of Kenya had violated the right to life, property, natural resources, development, religion and culture of the Ogiek, under the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

‘Important step’

“This judgment and award of reparations marks another important step in the struggle of the Ogiek for recognition and protection of their rights to ancestral land in the Mau Forest, and implementation of the 2017 judgment of the African Court,” said Francisco Calí Tzay, UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples.

The Court ordered the Government of Kenya to pay compensation of 57,850,000 Kenya Shillings (approximately $488,000), for material prejudice for loss of property and natural resources, and a further 100,000,000 Shillings for moral prejudice suffered by Ogiek people, “due to violations of the right to non-discrimination, religion, culture and development”, according to a statement issued by the UN human rights office, OHCHR.

In addition, the Court ordered non-monetary reparations, including the restitution of Ogiek ancestral lands and full recognition of the Ogiek as indigenous peoples.

The Court also requires the Kenyan Government to undertake delimitation, demarcation, and titling, to protect Ogiek rights to property revolving around occupation, use and enjoyment of the Mau Forest and its resources.

Furthermore, the court ordered Kenya to take necessary legislative, administrative or other measures to recognise, respect and protect the right of the Ogiek to be consulted with regard to development, conservation or investment projects in their ancestral lands.

They must be granted the right to give or withhold their free and informed consent to these projects to ensure minimal damage to their survival, the ruling said.

Expert testimony

The independent UN rights expert Mr. Calí Tzay, provided expert testimony to the Court in the landmark case, based on the mandate’s long-standing engagement in the promotion and protection of the rights of the Ogiek.

“I welcome this unprecedented ruling for reparations and acknowledge that the decision sends a strong signal for the protection of the land and cultural rights of the Ogiek in Kenya, and for indigenous peoples’ rights in Africa and around the world,” he said.

The UN expert urged the Government of Kenya to respect the Court’s decision and proceed to implement this judgement and the 2017 ruling by the court without delay.

First climate agreement to center Indigenous voices gains international support

The Escazú Agreement establishes the relationship between human rights and environmental protections. The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues urged its member states to adopt it.

The first climate agreement focusing on Indigenous perspectives continues to gain international support after the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues urged its member states to adopt the agreement in its final report which was released last month.

Known as the Escazú Agreement, the plan was a recurring topic throughout the permanent forum’s 21st session, and its side events, in April and May in New York City, in which government, tribal and community leaders discussed vital issues affecting Indigenous populations throughout the world.

“The Escazú Agreement is the first instrument that includes provisions on the protection of human rights defenders in environmental matters,” the report states.

The permanent form’s annual session is considered the world’s largest gathering of Indigenous leaders and the final report provides expert advice and recommendations on Indigenous issues to the UN system through the economic and social council.

In 2000, the United Nations Economic and Social Council established the permanent forum to discuss Indigenous issues relating to economic and social development, culture, the environment, education, health and human rights.

The council is then expected to make recommendations to the UN General Assembly, member states and other agencies. It’s considered a vital instrument for disseminating information about Indigenous people on an international level.

The permanent forum’s newly elected Chair Darío José Mejía Montalvo, Zenú, talked about the agreement during his opening remarks on the first day of the session.

“Recall that in combating climate change, Indigenous people are mainstays,” Montalvo said. “This is not a fashion, not motivated by needs and trends on social networks, it’s our way of life. We value and respect all efforts to protect the planet.

“Our existence dates from before the existence of borders,” he said.

He went on to explain the significance of the Escazú Agreement, then urged those states that have not yet subscribed to the agreement to adopt it and for those that have to implement it faster.

According to environmental defenders like Patricia Gualinga the most effective way to protect rainforests, like the Amazon, is by protecting the rights and sovereignty of Indigenous people and the Escazú Agreement could potentially be a powerful mechanism in doing that.

Gualinga is a Kichwa leader from Sarayaku, Ecuador and a spokeswoman for Amazonian Women – a coalition of women environmental and land defenders, better known as Mujeres Amazónicas Defensoras de la Selva.

“It’s hard to describe the smell of such pure air when you’re in the rainforest,” she told Mongabay News in May. “When you go into these sacred forests, you feel so much closer to the forces of creation.” In these spaces, beyond encountering an incalculable natural wealth, one can connect to the basic principles of energy and equilibrium, she told the news outlet.

The Escazú Agreement

It’s formally known as the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean. It was signed in 2018 in Escazú, Costa Rica after years of planning, preparation and negotiations between Latin and Caribbean countries. Currently of the 24 countries that have signed the agreement 12 have ratified it into law.

One of the agreement’s pillars starts with ensuring the timely generation and dissemination of environmental information to impacted communities.

“Such reports shall be drafted in an easily comprehensible manner and accessible to the public in different formats and disseminated through appropriate means, taking into account cultural realities,” the agreement states. “Each Party may invite the public to make contributions to these reports.”

The Escazù Agreement entered into force in April 2021 and a year later, as outlined, the first Conference of the Parties took place. The conference established public participation during the three days of the event, which began with tense debates on the matter.

“Eliminating the participation of the public is removing the very spirit of this agreement,” said Calapucha, a member of the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin, during that first meeting.

The moment was sparked by several tense minutes during the negotiations when the Bolivian delegation presented a project that would eliminate the inclusion of the public in the board of directors, according to Mongabay News. Another topic was the creation of a task force specifically focused on monitoring the situation surrounding environmental defenders, according to the news outlet.

That first Conference of Parties of Escazú – which was in Santiago, Chile – marked the first step toward effective implementation of the agreement but during one side event, hosted by the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network, women voiced their lingering concerns.

Women for Climate Justice

Gualinga, the Amazonian Women spokeswoman, was one of eight featured speakers advocating for the agreement during the Escazú conference side event, “Implementing the Escazú Agreement: Opportunities and Implications for Women Land Defenders and Human Rights Advocates.”

She’s the daughter of a traditional healer who testified in front of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to protect their ancestral territory. She knows, first hand, when Indigenous people mobilize they have the power to halt extractive projects in their tracks but they risk arrest or even death.

“Without proper implementation there won’t be justice” Gualinga said about the Escazú Agreement, adding that Indigenous women can speak up and lead forward to a more sustainable future. Many voiced concerns about the threats experienced by female land defenders, saying they are not unusual and adding that there’s a “lack of political will” on national and international level to protect people.

“We need to use this lever as much as we can to protect defenders of land and women who are putting their bodies on the line to protect biodiverse areas,” said Osprey Orielle Lake, executive director of WECAN, the organization that hosted the virtual side event. Lake pointed to the entrenched colonial and patriarchal systems in place that will make it difficult for this “unique and transformative agreement” to provide a promising path forward.

Environmental and human rights abuses

The permanent forum’s final report urges member states to adopt the Escazú Agreement because it’s a necessary measure to ensure rights, protections and safety of Indigenous people.

“The Permanent Forum regrets the continuous killings, violence and harassment targeted at Indigenous human rights defenders, including Indigenous women, in the context of resisting mining and infrastructure projects and other such developments,” according to the report. “The Permanent Forum therefore invites Member States to honour their human rights obligations.”

According to a 2021 report, the previous year had been the worst year on record for killings of environmental defenders, with more than half of the attacks taking place in only three countries: Colombia, Mexico and Philippines.

The report was published by Global Witness, an international nonprofit organization that has been investigating environmental and human rights abuses and linking natural resource extraction with widespread attacks and killings. However, more recent data shows a dramatic increase in assassinations.

So far in 2022, 99 defenders have been killed as of July 4, according to the Institute of Studies for Development and Peace which tracks murders in Colombia. Roughly a third of those killed were Indigenous or Afro-descent.

Many Indigenous communities are attacked and displaced, forced to leave their territories due to legal and illegal extractive projects, like mining and logging, as well as narco-paramilitaries. Experts say the increased violence is spilling into neighboring rural communities.

The impacts of the agreement reach beyond Indigenous communities. It’s also gained support from multilateral banking institutions and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which recognize the importance of the agreement as a tool to generate certainty and stability in investments. Leaders are hopeful that, with support from the permanent forum, the Escazú Agreement can continue to generate support and proper implementation.

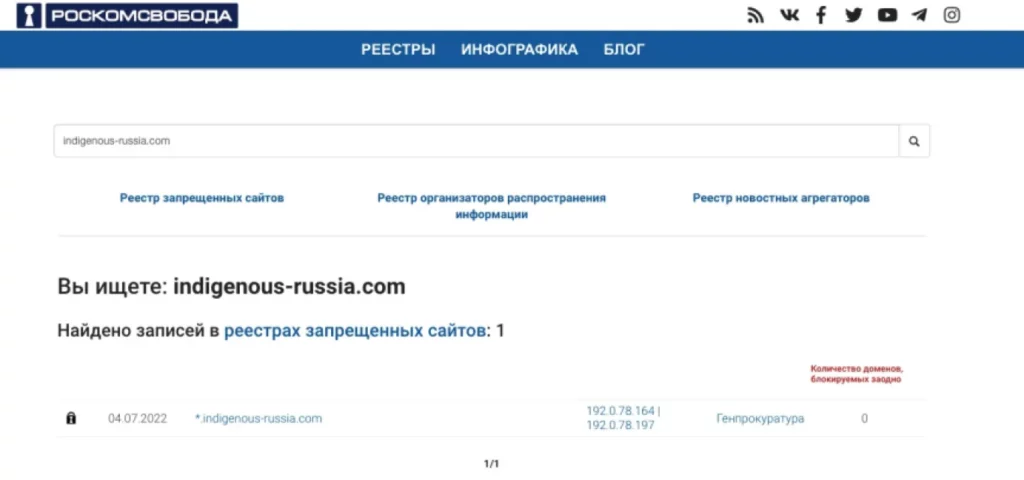

The Russian Government blocked Indigenous Russia immediately after the EMRIP session

My name is Dmitry Berezhkov, and I am the editor-in-chief of the Indigenous Russia web page. This web page was created several years ago as a small blog to follow indigenous rights development in Russia.

Today iRussia is an information center whose main aim is to deliver information about the Russian indigenous issues to international audiences and provide information back about international events for indigenous communities in the Russian Arctic, Siberia and the Far East, both in Russian and English. iRussia today is also a data center that preserves information about indigenous rights violations in Russia and keeps information for further use by human rights defenders, journalists, researchers, politicians and other interested stakeholders.

Keeping data is a critical job during times when the Russian Government is trying to stop information dissemination, cover the truth and block independent points of view. Countless times we met with the situation when Russian authorities or their vassals tried to delete or distort Internet information about indigenous rights violations or environmental pollution in Russia. That is why our small team of editors and correspondents strongly believes that such work is essential both for Russia and its indigenous peoples, as well as for the international community.

Indigenous Russia also produces reports alone or in partnership with our allies on indigenous rights for the international audience, UN human rights bodies and Russian authorities themselves. We think this is an important tool for changing and strengthening the means to protect the rights of indigenous peoples in Russia.

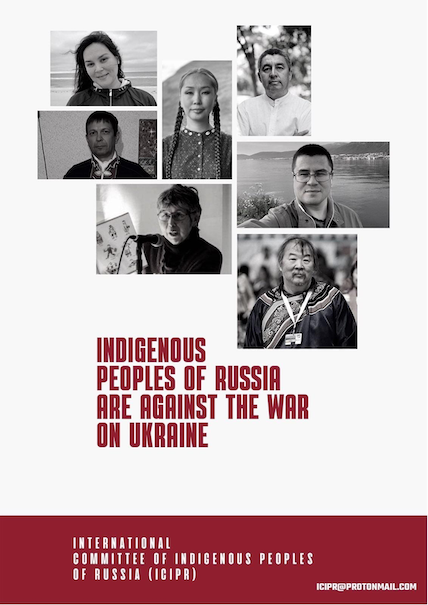

But because of this activity, I could say that Russian authorities, as well as big Russian corporations, don’t like Indigenous Russia. Today as Russian Federation has started a Great War against Ukraine, we can say that iRussia became the last independent media that publishes strong criticism of the Russian authorities and Russian corporations for violations of indigenous peoples’ rights in Russia on a daily basis. Frankly speaking, they even hate us for our job today. This hate became even more after the start of the Russian war against Ukraine as iRussia supported the establishment of the new international organization – the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (ICIPR), which openly spoke against the war and appealed to indigenous soldiers in the Russian army to not participate in hostilities.

As you maybe know, two weeks ago, the UN Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples organized its 15th session in Geneva. On the first day of the session, one of the ICIPR members – Yana Tannagasheva, made a statement in which she critiqued Russian authorities and mining companies in the Kemerovo region and Taimyr for violations of indigenous peoples’ rights. Her report triggered an aggressive response from a high-level Russian official, the Deputy Director of the Human Rights Department of the Russian Ministry of foreign affairs Sergey Chumarev, right in the EMRIP session hall.

This unprecedented incident of aggressive play of the state official against an indigenous delegate provoked hot discussion among participants and was reflected in many publications during and immediately after the EMRIP session. Many states and indigenous representatives expressed their support for Yana Tannagasheva and protested against the aggressive behavior of the Russian state officer.

I am personally as a member of ICIPR and an editor of Indigenous Russia made a statement with the protest against such actions of the Russian state delegation during the second day of the forum. And within several hours after that, I received a letter from the legal department of WordPress, an iRussia hosting provider and one of the biggest world internet companies:

“Hello,

A Russian authority — the Federal Service for Supervision in the Sphere of Telecom, Information Technologies and Mass Communications (ROSKOMNADZOR) — demanded that we disable the following content on your WordPress.com site: https://indigenous-russia.com/.

Typically, we would comply with orders such as this to keep WordPress.com accessible for everyone in Russia.

However, we do not believe that this specific order has been submitted in good faith by the Russian Government, and so we are not complying with their demands.

For your reference, we included a copy of the complaint below. No reply is necessary, but please reply if you have any questions.

Thank you.”

I believe that was the immediate reaction of the Russian authorities to the words of truth in the UN building. The Russian Government ordered to delete the whole web page within 24 hours. Below we publish the entire Roskomnadzor’s letter, which was sent to WordPress. This is interesting that they didn’t ask to delete some definite articles which, according to their understanding, violate the Russian legislation. Instead, they demanded to delete the whole website.

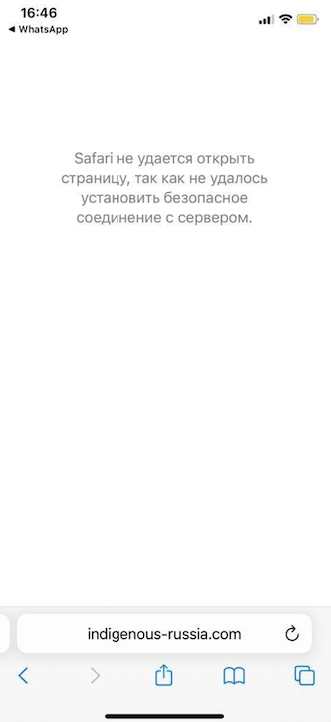

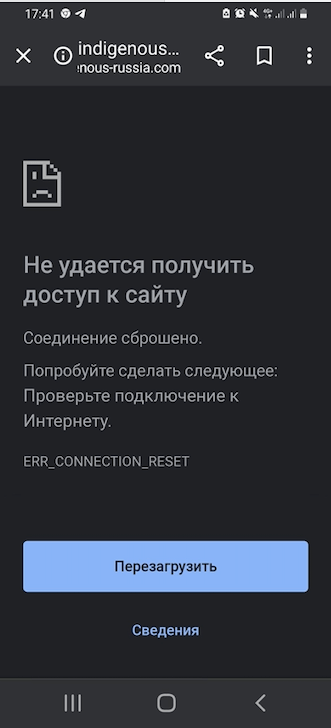

To WordPress credits, it didn’t follow the order of the Russian Government, so our web page continues to work but only for the international audience, unfortunately. Two days after that letter, we started to receive messages from our Russian readers that they couldn’t reach the web page as ROSKOMNADZOR included iRussia into the list of prohibited web resources and bunned the access for the Russian audience.

This is how the Russian Government protects its own citizens from receiving “dangerous” information about the indigenous peoples’ rights. However, we continue to work for our Russian readers and international ones. We will develop our social networks accessible in Russia: WhatsUp, Telegram, YouTube channels, email lists, and other means available for remote indigenous communities.

I hope you will continue to receive unbiased, timely and accurate information about indigenous rights in Russia and international development in this sphere.

I would like to end this address at this point but must add one more unfortunate but necessary fact. As far as we know, the Russian authorities received the formal request to block Indigenous Russia from RAIPON – the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North. This is the oldest and biggest Russian indigenous organization where we all worked some years ago, whose main aim, according to its Statute, is protecting indigenous rights and which now become an obedient instrument of any orders by the Russian Government.

Dmitry Berezhkov. An address to readers.

Yana Tannagasheva’s statement at EMRIP 15th session. ITEM 9: Thematic discussion on Violence against Indigenous Women

4-8 July 2022

Oral statement of Ms. Yana Tannagasheva on behalf of

International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (ICIPR)

Thank you, Madame Chair,

Dear brothers and sisters,

Yesterday, within the walls of the UN, we saw the unacceptable, undiplomatic behavior of a representative of the Russian government. This situation paints a general picture of the Russian aggression against the indigenous peoples of Russia and Ukraine, in particular indigenous women. Such aggressive actions fully paint the picture of the methods of the Russian government that means “the best defense is an attAck.” Yesterday they attacked, and today they present themselves as victims. This happened with the attack on Ukraine: they started the war first, because, supposedly, Ukraine could attack them.

The rights of indigenous women in Russia are being violated, but little is said about it. Our women know and are accustomed (to the fact that it is almost impossible to achieve justice. The rights of indigenous women in Russia are violated both at work and at home. The number of cases of domestic violence by husbands of indigenous women, especially in remote villages, is not monitored by anyone, and this is one of the serious problems in such areas. The police ignore the problem of domestic violence. Women have no one to turn to. They have no access to information and justice.

The rapid development of industrialization pushed by the Russian government and companies, has a powerful negative impact on the traditional way of life and the health of women and children. The persecution of indigenous women by the Russian authorities and mining companies, as in my case, the fabrication of cases, discrimination, the creation of a negative picture of indigenous women are part of the repressive methods of the Russian authorities. With the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, the situation of indigenous girls and mothers became catastrophic both in Russia and Ukraine. A representative of the Russian government aggressively asked me yesterday if I had been to Donbass in Ukraine. I have not been to Ukraine, but my friends from the Donbass tell me what kind of “peace” Russia brings: with blood, bombs and deaths.

Dear Madame Chair,

I make a recommendation to the Expert Mechanism, the Human Rights Council to take into account and investigate the incident that took place during this session, not only as a particular case of harassment against me, but also in general the situation of the indigenous women of Russia and Ukraine.

Yana Tannagasheva’s statement at EMRIP 15th session. Agenda #3 “Study on Treaties, agreements and other constructive arrangements, between indigenous peoples and States”

ITEM 3: Study on Treaties, agreements and other constructive arrangements, between indigenous peoples and States, including peace accords and reconciliation initiatives, and their constitutional recognition

EMRIP 4-8 July 2022

Oral statement of Ms. Yana Tannagasheva on behalf of Society for Threatened Peoples / International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (ICIPR)

Thank you Mr/Madam Chair.

As a representative of the Shor People from southwestern Siberia, who has been directly affected by the Russian regime and coal mining companies, I want to draw your attention to the violations of the rights of indigenous peoples by the Russian authorities and mining companies.

Unfortunately, no treaties regarding indigenous peoples are in force in the Russian Federation. A vivid example of this is the Kazas village in Kemerovo region, where I am from. The village was burned down by the coal company 8 years ago. The case of this village and violations of the Shor people rights was considered by the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. The concluding observations of the Committee were addressed to Russia: to restore the rights of the Shor people. However, the rights of the Shors continue to be violated by coal and gold mining companies, and the Russian authorities have both lied in their reports and continue to provide false information. Moreover, the Russian regime is increasing pressure and repression on those representatives of indigenous peoples who openly fight for their lands, territories, the right to self-determination and, in general, openly express their position.

I express concern that the Russian authorities and mining companies are manipulating representatives of indigenous peoples, using their vulnerable position to promote the state policies and propaganda both on national and international level. This applies, for example, to the Norilsk Nickel company, whose accident occurred in 2020, which became the largest oil spill in the Russian Arctic. This caused irreparable harm to the living environment of the indigenous peoples of Taimyr, negatively affects their nutrition, health, and psychological state, especially women and children. Today, the Russian authorities and Norilsk Nickel are trying to set a positive image of interaction with indigenous peoples at the international level by promoting the implementation of the FPIC principle. However, the indigenous peoples who live there tell us otherwise.

In general, the poor situation of the Indigenous Peoples of Russia was difficult even before the war, but now it has only worsened. Today in Russia it is almost impossible and dangerous to speak openly, to express your position freely. Indigenous peoples are criminalized in various contexts. Threats and harassment are more often directed against persons involved in the protection of environmental rights, land rights, and recently against those who openly protest against the war with Ukraine.

In conclusion, Mr/Madam Chair, I would like to recommend:

- Request the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples to pay special attention in future reports to the situation of the indigenous peoples of Russia, controversial situations, the implementation of the recommendations of treaty bodies, and also to investigate issues related to the criminalization of representatives of indigenous peoples who protect their lands, territories, resources.

- Recommend to the Human Rights Council that the mandate of a Special Rapporteur on the situation of indigenous peoples in situations of interstate conflict be established. And also include the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in the list of standards of the universal periodic review.

Thank you for your attention!

Dmitry Berezhkov: “How does the militarization of Russia’s internal politics, social life and economy affect indigenous peoples’ development in Russia?”

15 Session of the Expert Mechanism on the rights of indigenous peoples. 4 July 2022, Geneva

EMRIP Side-Event: The influence of the aggression of the Russian Federation in Ukraine on indigenous peoples of Russia – https://indigenous-russia.com/archives/22391

Presentation by Dmitry Berezhkov: “How does the militarization of Russia’s internal politics, social life and economy affect indigenous peoples’ development in Russia?”.

Thank you very much, mister chair.

The war in Ukraine has many different aspects. And it influences indigenous communities in Russia in different ways, sometimes very unexpected ones.

Indigenous soldiers

The most obvious item is the dying of indigenous soldiers as members of the Russian army forces. I don’t approve of them; of course, they must be punished by international law for participating in the war.

At the same time, we must remember that Indigenous Peoples in Russia remain among the poorest parts of the population. Their social and economic development and life expectancy are far below the national average. Sometimes military service is the only way for the young man to earn some money. We also need to understand that most Russian soldiers didn’t know they would be sent to the war by the government. And, of course, this is a great tragedy for small numbered indigenous peoples if young men die for some imperial ambitions of the Russian dictator somewhere thousand kilometers away from their home communities.

We know a village where live only two hundred individuals and five young indigenous soldiers are fighting in this war from there. And this whole indigenous Nation is less than two thousand persons itself. Many died. We have confirmed the deaths of indigenous soldiers from Chukotka, Khabarovsk Krai, Tyva, Buratia, and other regions. But we can not even estimate the total numbers. The only way is to study dead soldiers’ open databases and find their indigenous names. But many of them have Russian names, of course. So this research has to be done in the future.

Economic crisis

In Russian state media, you don’t find any substantial news about the negative influence of the war on the Russian economy. According to Putin’s propaganda, the Russian ruble has become more strong currency since February; the Russian companies have organized successful import substitution since Western businesses fled the country. We even have now own analog of Macdonalds.

At the same time, the Russian economy, social life, communications, prices, and the everyday life of ordinary people have changed significantly. The costs for food, energy, fuel, delivery for remote indigenous communities have increased drastically. We know villages in Siberia that suffer from stopping air traffic because it became unprofitable to deliver goods there for local businesses. Many remote villages suffer from the absence of pharmaceutical drugs which previously Russia imported from the West. People must buy the cheapest inferior Russian analogous medications, negatively influencing their health. This hit most small villages in the remote regions where indigenous peoples live.

Propaganda

Indigenous peoples as a part of Russian society are today the subject of unprecedented state propaganda. For example, they are now trendy on the Russian Internet videos in which indigenous artists dance and sing to support Vladimir Putin and the Russian Army. While these actions are often initiated by state officials or real supporters of the war in Ukraine, like representatives of the Russian Association of indigenous peoples of the North (RAIPON), we receive many reports that indigenous performers usually don’t know for what purposes they are dancing until they see the videos published on the Internet.

We know that at least several civic activists from indigenous peoples publicly criticized the government for the war in Ukraine and were fined by police according to the new restrictive legislation and stigmatized by society for their antiwar position. The saddest aspect of this is that in some cases, authorities received information about such “crimes” from representatives of RAIPON.

The war, mining companies and indigenous peoples

The other aspect of the war and its influence on indigenous peoples of Russia is the rapidly changing rules for doing extractive business on indigenous lands. As you know, the Russian Federation continues to receive the most significant share of the state income from extracting minerals and other resources from indigenous peoples’ lands in the Russian Arctic, Siberia and the Far East. This share is more than half of the Russian export. President Putin uses these hundreds of billions of dollars to buy a weapon to kill innocent Ukrainian people, including indigenous peoples like Crimean Tatars.

But now, we are met with a situation where the government and mining corporations use the pretext of war to loosen the environmental requirements for extractive business operations. Governmental and business propagandists openly say that Russia today is in a fight with US and NATO in Ukraine, and people have to be patient and not ask “too many” environmental questions to business. The ecological legislation is changing to lose any opportunities for civil society to protect the environment.

Western companies, which were most advanced in using the international law standards, including indigenous peoples’ rights and environmental standards, are fleeing the country while their shares go to the state or to Russian oligarchs. To substitute, Western investors and technologies, Russia tries to attract money and technologies from Chine or India, which pay much less attention to environmental standards or human rights.

Persecution of human rights defenders

The huge challenge today for Russian indigenous peoples is suppressing by the state and fleeing from the country the most prominent independent environmental, legal and media experts. Lawyers, journalists, and environmentalists who previously supported indigenous communities today have to work outside Russia, be silent or are subjects of criminalization themselves. The others have a tremendous amount of work with numerous cases.

Sergey Kechimov case

I can give you a small but obvious example. There is a sacred lake Imlor in Western Siberia in Khanty-Mansiisk autonomous okrug. There lives Sergey Kechimov, who is a Khanty reindeer herder. He lives there with his wife only. Other Khanty left the lake area many years ago because there operates one of the biggest Russian oil companies, Surgutnefegaz, which polluted all territories around the lake. I will not be able to describe his life’s full and tragic story in such a short presentation. Today, oil facilities, pipelines, roads and infrastructure surround the lake’s perimeter several meters from the water.

Several years ago, after one of their regular conflicts, the oil workers blamed him for threatening their lives. So they applied to the police, which sent the case to the court. After several months of investigation, the court sentenced Sergey Kechimov to communal work. That was an unlawful decision for many reasons. For example, the police officers fraudulently forced him to sign a confession of guilt using the fact that Kechimov doesn’t speak Russian well. I can not describe all the details here, but we consider this case pure evidence of indigenous rights defenders’ criminalization tendency in Russia (here you can find more details)

Those days the Russian and international media widely publicized the story of Sergey Kechimov. He received legal and media support from many Russian and international human rights and environmental organizations, including Greenpeace, IWGIA, TheGuardian, Glovalvoices and others. It was not comfortable for Surgutneftegaz to be involved in the prosecution of the indigenous rights defender, so their representatives didn’t appear during the court sessions.

Today, the story repeats. After another conflict between the oil workers with Sergey last September, they beat him but then applied to the police with a false statement and blamed him again for threatening their lives. We believe that by this action, Surgutneftegaz is trying to frighten indigenous peoples and Sergey Kechimov in particular because he is now the last reindeer herder who lives near the Imlor lake with his wife.

But today, this case doesn’t attract media attention as Putin’s regime destroyed the last independent media after February 2022. He has no lawyer as human rights and environmental networks have been shrunk in Russia since the start of this new phase of the war against Ukraine. He even can’t hire the local commercial lawyer as many of them are afraid to protect indigenous rights defenders in court.

The influence of the war on Russia’s indigenous peoples’ briefing note

These are only some aspects of the influence of the Russian aggression against Ukraine on the indigenous peoples of Russia. We are prepared a briefing note on that topic which we will send to the EMRIP secretariat, but we will continue to work on this to prepare the full report in the future.

Thanks for your attention.

ICIPR statement at EMRIP 15th session. Agenda # 10. Future work of the Expert Mechanism

Agenda # 10. Future work of the Expert Mechanism, including the focus of future thematic studies.

Thank you, Madam chair.

Dear colleagues, during the first day of the Expert Mechanism session, we witnessed the scene when the Russian Federation representative intimidated a member of the indigenous Russian delegation, Mrs. Yana Tannagasheva, here in this room.

As you remember that after the incident, we, as members of the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (ICIPR), made a statement of protest against the unacceptable behavior of the Russian state representative in the UN building, where all delegates must be protected by international law and even by the spirit of the UN philosophy. And we are grateful to many indigenous and states’ delegations who also protested against the aggressive approach of the Russian representative.

That was an unacceptable and extraordinary incident within the UN building, but unfortunately, we are used to such behavior inside Russia. The way of harassment, intimidation and criminalization of indigenous rights defenders, human rights activists in general, independent media is usual for the Russian authorities.

Just after our statement, we received the letter from the hosting provider of our web page “Indigenous Russia,” where we publish news from this forum for our indigenous brothers and sisters in Russia. Today this is the only information channel independent from authorities that regularly publishes information about indigenous peoples of Russia. Our web host said they received the order from the Russian government to delete our web page from the Internet within 24 hours because we publish information about indigenous peoples’ rights violations and the war in Ukraine, which is different from the official Russian propaganda.

That is how Russia immediately reacted to the words of truth about indigenous rights violations that sounded in this hall. We, anyway, continue our work to deliver information about indigenous rights violations in Russia to international society. Today we prepare a briefing note on the influence of the Russian aggression against Ukraine on the indigenous peoples of Russia, which we will deliver to the EMRIP secretariat.

We support the decision of the EMRIP to extend the time for the militarization of indigenous lands report and kindly ask you to include the topic of the influence of the Russian war in Ukraine on indigenous peoples both of Ukraine and Russia in this thematic study. As members of the ICIPR, we will be glad to provide additional data on this topic for the Expert Mechanism.

For better understanding of the topic during the preparing such report we request Expert Mechanism to organize consultations or expert workshop with participation of indigenous peoples of Ukraine and Russia on that topic.

Our only request to the Expert Mechanism is – do not include in this work representatives of the Russian state, Russian experts in the UN or NGOs from Russia which supported aggressive policy of President Putin towards Ukraine as representing a side of the conflict responsible for the war. Thanks for your attention.

Dmitry Berezhkov. International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (ICIPR)

RUSSIAN INDIGENOUS SPOKESWOMAN FACES INTIMIDATION AT THE HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL

Exiled Siberian Shor indigenous representative Yana Tannagasheva had just finished reading a statement on Monday about human rights violations in her homeland when she was subjected to aggressive behavior by a representative of the Russian Mission to the UN in Geneva. The Russian diplomat’s open hostility, in the midst of the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’ signature event, prompted a strong reaction from the other participants, who circled a weeping Yana, acting as a human shield.

UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Francisco Cali Tzay supports ICIPR delegate Yana Tannagasheva who faced with the aggression of the Russian state representative. July 2022 Geneva, 15th session of EMRIP

Multiple witnesses to the scene agree that the incident is without precedent at the UN. One told us: “This goes to show that Russia is no longer concerned by its public image. Even the most basic codes of communication in what is supposed to be a safe space for discussion are no longer respected.”

UNACCEPTABLE INTIMIDATION

Kenneth Deer, the world-famous Mohawk Nation spokesman, was up next. Instead of reading his prepared statement, Deer improvised a heartfelt speech in support of Yana Tannagasheva: “We are truly upset by the behavior of a state representative to intimidate indigenous peoples who have every right to be here and speak truth to power. If that individual was an NGO, we would have had his badge pulled. […] We ask that the Bureau take action, so that this does not happen again.” A standing ovation ensued.

INCREASING PRESSURE ON INDIGENOUS GROUPS IN RUSSIA

The July 4 incident is an illustration of the increasing pressure that Russia is putting on its more than 160 ethnic minorities. Yana, currently a refugee in Sweden, fears for her life, as well as the wellbeing of her loved ones. She told The G|O that indigenous peoples in Russia have become a target since the beginning of the war: “Any form of criticism against the government is being crushed,” she told us. “Before I made the trip to Geneva, my husband was very worried about my participation in the Geneva meeting. I have been vocal in criticizing the coal mines that are destroying my region in many international forums. There is a lot of money at stake in these operations and I’ve made some powerful people angry.”

Christoph Wiedmer, co-director of the Society for Threatened Peoples, says that communication with indigenous minorities has become impossible. “I was extremely shocked by what happened here at the UN, on Monday. There has been increasing intimidation from the Russian government on indigenous peoples, but I would not have expected them to make them so public. Russia has just crossed an unprecedented line.”

He adds, “By such actions, the Russian government is trying to frighten civil society activists who contribute to human rights causes on [the] international level. Many of the indigenous people in Russia are extremely scared. An already tense climate has worsened significantly. We wonder if this is just an intimidation, or if this is the first step to an actual attack?”

The Russian Mission to the UN declined The Geneva Observer’s request for comment.