Russia’s War on Ukraine: Colonial Efforts on Two Fronts

Russia’s war in Ukraine is on its 211th day. As the number of fatalities wrought by Russia’s invasion escalates, Russian imperialism and colonial drive are further emphasized, both in Ukraine and Russia. The unlawful encroachment on the sovereign nation of Ukraine, acts of violence, and destabilization of the region are all efforts at new colonization. An overwhelming number of Russian soldiers killed in Ukraine come from Russia’s impoverished “ethnic republics”, which are also home to Indigenous Peoples, already devastated by economic instability, and beset by discriminatory official policies and social norms alike. The war has also put immense pressure on Russian civil society, making disagreement with Russia’s actions and anti-war sentiment and action chargeable, leading to a tremendous increase in censorship, criminal prosecutions, and enforcement of new restrictive laws.

The Russian State and local governments are increasingly reluctant to release information on the numbers of service people killed, much less on the ethnic identities of the deceased; nevertheless, independent news sites such as Vazhnie istorii (IStories) and MediaZona have conducted in-depth investigations into the numbers. Through analysis of thousands of publications, these studies reveal the number of fatalities to be significantly higher than the Russian government has put forth. Furthermore, one of MediaZona’s main conclusions was that “most of the dead soldiers are very young people from poor regions.” While “poor regions” does not necessarily denote areas where Indigenous communities live, Russian imperial politics have instituted, and continue to foster, poorer socioeconomic circumstances in areas where the majority of Russia’s Indigenous Peoples reside.

Military censorship has made it incredibly difficult to find reliable data and to form an accurate understanding of the numbers and demographics of Russian military personnel killed in Ukraine. The exact count of Russian soldiers killed is not known and estimates vary widely. The Russian Ministry of Defense has only released official data on losses twice: March 2 (498 dead) and March 25 (1,351). The General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine reports Russia’s military death toll is around 35,000. An analysis of publications from regional media and social networks conducted by MediaZona, in collaboration with the BBC and a team of volunteers, confirms 6,219 deaths as of September 23. IStories’ investigation, which is updated daily, has verified 6,083 names of the deceased. MediaZona and IStories both emphasize that these numbers solely reflect data their teams have been able to verify through open sources rather than actual losses. In early June, the military prosecutor’s office in the Kaliningrad region demanded that the Pskov-based media site 60.ru take down their lists of deceased soldiers. This started a mass removal of lists from other regional media outlets. The Kaliningrad court’s decision, which stated that this information divulges State secrets and weakens morality, has become a norm throughout regions of Russia though individual obituaries continue to be published by regional media and social media public networks. As a consequence of the war, Russia’s mortality rate of young people has increased by approximately 20%. IStories’ investigative reports show that citizens of Saint Petersburg and Moscow, where over 12% of Russia’s entire population live, are hardly present among the fatalities. In contrast, in less heavily populated regions of the country, the mortality rate of young men has simply skyrocketed.

The “ethnic republics” most impacted by this current situation include, but are not limited to, Dagestan, Buryatia, Chechnya, Bashkortostan, and Altai. The Republics of Dagestan and Buryatia rank first and second, respectively, among these regions. The number of deaths of people from Dagestan has increased by 130% during the war; in Buryatia, 110% (according to the Telegram channel “Demography fell”, in the first three months of the war, confirmed deaths of military personnel from Buryatia increased the mortality rate of Buryat men ages 18–45 by 70% and mortality rate of young men under 30 by 270%). In Buryatia, there is at least one funeral of a soldier daily. The disproportionate number of dead soldiers who come from these regions exemplifies contemporary Russian colonialism––ethnic republics are overwhelmingly economically depressed though often sites of lucrative, intensive extractive industries; unemployment is high, particularly in villages, making military enlistment one of the only ways for young men to earn money; and ubiquitous patriotic propaganda, alongside a history of conditioning and institutionalizing ethnic Russian primacy, instills incredibly complicated feelings of loyalty to nation(s).

In March 2022, military registration and enlistment offices began to actively recruit contractors for a “special operation” without specifics (the war in Ukraine is called the “special operation” in Russia). Most of these aggressive recruitments unfolded in Russia’s economically depressed regions. Although varying among regions, in Dagestan offered salaries for enlisting in the “special operation” began at 177,000 rubles ($2,800 USD) for the rank of private, and went up to 215,000 rubles ($3,401 USD) for the rank of ensign. These numbers are astronomical when considering that the average salary in Dagestan is slightly more than 32,000 rubles ($506 USD). In 2020, Buryatia ranked 81st with regard to quality of life out of 85 regions in Russia and a 2022 RIA Novosti (Russian state-owned news agency) study based on data from the Ministries of Health and Finance, the Central Bank, and other open data sources found that out of these same 85 regions, Buryatia was 69th in terms of the population percentage living below the poverty line (19.9%). The regions with highest population percentages living below the poverty line in 2022 were the Republics of Tuva, Ingushetia, and Altai––notably also “ethnic republics” with Indigenous populations.

In addition to financial incentives, military service is often seen as an important, respectable social elevator and an ideological civil position across Russia, and especially in these areas. For example, in Buryatia the city of Kyakhta is known as a “military city” where the 37th Independ Guards Motor Rifle Brigade is based, in which at least four thousand people serve, and where “almost every boy dreams of a military career”. While such military cities exist, it is often smaller villages that supply the army with people and, consequently, bear the greatest losses. Lack of employment opportunities are often felt throughout Russia’s ethnic republic, pushing general migration outflows to increase, but these strains are even more acute in villages. Inculcation of patriotism, which is a key part of recruitment for Russia’s war on Ukraine, is increasingly rooted in World War II. Monuments to the victories of the USSR during World War II (called the “Great Patriotic War” in Russia) are everywhere in Russia––from large cities to small villages like that of Selenduma (Selenginski district, Buryatia).

During World War II, 386 Selenduma residents went to the front where almost half died. In their honor, a victory monument was erected in the village with all the names of the deceased. Today, the village of Selenduma has a population of 2,700 and the head of the rural administration’s reports that twenty three residents left for Ukraine means that every twentieth man (aged 15–44) is gone. The village of Kani (Kulinskii region, Dagestan)––once an extensive community––is now populated by around thirty families. In Kani there is the quintessential monument to those who died in World War II. So far, twenty men from the village have left for the war.

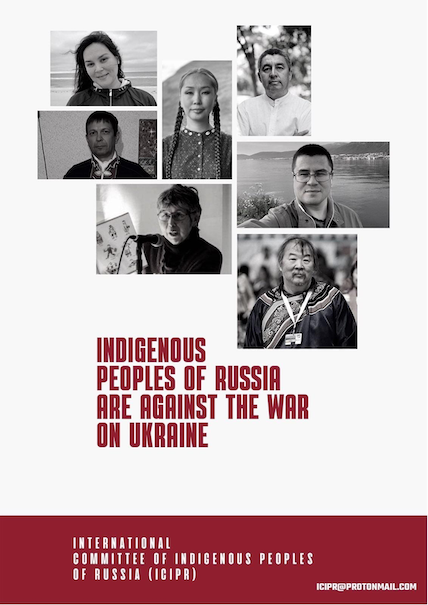

As elsewhere in Russia, the war has split societies, including Indigenous communities. Attitudes about the war are complicated and vary across and within regions. Ethnic republics are generally split over their loyalty to Putin and Russia and stance on the war. On the one hand, public demonstrations of support for the Russian invasion are frequent, but they are, time and again, met with resistance. There are Indigenous people who support the war and believe it to be righteous, protecting not only Russia, but their own communities. On March 1, 2022 the Russian Association for Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) issued a statement and public letter in support of the invasion of Ukraine, thereby backing the killing of civilians, women, children, Indigenous Peoples, and soldiers living in Ukraine. There are also Indigenous people who openly condemn the war, in particular mothers whose children have been sent to war. On March 11, the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia––comprised of “representatives of Indigenous Peoples living outside of Russia against [their] will”––released a statement of solidarity with the people of Ukraine in which they condemned RAIPON’s open endorsement of the war.

These feelings reflect convoluted attitudes and identities throughout the country. Opposing the “special operation” is dangerous. Anti-war initiatives taken on by civil society are increasingly met with severe, suppressive measures by the State, therefore, even if individuals oppose the war, vocalizing anti-war sentiment can result in fines, detention, harassment, intimidation, other forms of violence, and the already prevalent practice in Russia––arrests and imprisonment.

Prior to the invasion of Ukraine, Russian authorities had actively started using propaganda to preemptively justify a “special military operation” in Donbas. In the beginning of the war, Russian schools were given instructions for how to teach lessons about the war on Ukraine and similar recommendations were given to some Russian universities. The Ministry of Education sent elementary schools materials on how to lead lessons on “Anti-Russian sanctions”, “Heroes of our time”, and how to mitigate “fake news.”

Independent news and media sites in Russia have been blocked, state-operated news cannot publish or broadcast information that discredits the Russian government and its actions, and access to other media sources have been greatly restricted. In mid-March, Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, was banned in Russia due to allegations of extremist activities. The ban resulted in the blocking of Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and a slew of other websites (social media, news, civil society, government domains). Thus, having applications for these banned networking services downloaded on one’s phone is a punishable offense. In March, “public dissemination of deliberately false information about the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation”, “public actions discrediting the use of the Armed Forces, including calls for unauthorized public events,” and “calls for sanctions against Russia” were codified under amendments to the Criminal Code, which has made speaking out against the war a criminally liable act with punishment ranging from fines of thousands of rubles to imprisonment. According to data gathered by OVD-Info, an independent human rights media project, there have been 16,334 detentions for taking anti-war positions or related to anti-war protests since February 24, 2022 (this includes “preventive” detentions authorities practice using face recognition software). At the end of June, OVD-Info knew of 2,457 administrative cases filed against individuals for “discrediting” the army of the Russian Federation. Not only is pro-war propaganda infused into all aspects of Russian life and imperial ideology and nationalism institutionalized, non-compliance with them is exceedingly risky.

Nevertheless, there are Russians who, despite the risks, openly oppose the war. For many ethnic groups, the war on Ukraine is immensely evocative of Russia’s imperial conquest of their own traditional territories and historical and contemporary Russification policies. Ruslan Gabbasov, head of the Bashkir National Political Center, says that lingucide and ethnocide has been occurring and “[t]oday, genocide has been added to this both towards the Ukrainian people and towards the peoples of Russia, whose representatives are sent to far for slaughter”. This is not the first time in recent history in which the Russian State, in an all-too-familiar colonial practice, has recruited and sent contractors from ethnic republics to fight in imperialist-driven wars. Alexandra Garmazhaprova, a Buryat journalist and president of the Free Buryatia Foundation, which seeks to expose and dismantle racism and xenophobia in Russia and demystify information about the war, wrote in 2015 about the participation of Buryat soldiers in the war in southeastern Ukraine.

Not only are Indigenous ethnic minorities disproportionately dying in the State’s wars, they’re also deliberately used as the faces of wars, which often functions to distance war from a broader ethnic Russian public. The “national question”, which in the Soviet context described the two distinct modes in which nationhood and nationality were institutionalized, today manifests as paradoxical and concurrent State-upheld images of multinationality and ethnic Russian primacy. This question has taken on additional meaning in the context of the war on Ukraine. Preexisting anti-war and decolonial movements in Russia and diasporic communities and nascent ones, such as the Free Buryatia Foundation, are coming together to create a more united and collaborative movement. Members of Indigenous ethnic groups, such as Gabbasov and Garmazhaprova, are part of a larger phenomenon of anti-war national movements in which people of non-Russian ethnicity in Russia are simultaneously realizing a new sense of collective identity and a need to further distance themselves from Kremlin objectives in the name of the “Russian world.”

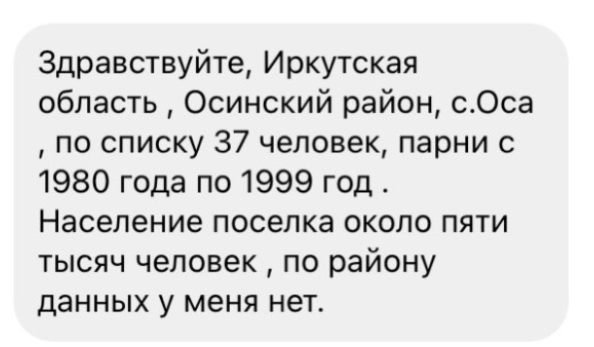

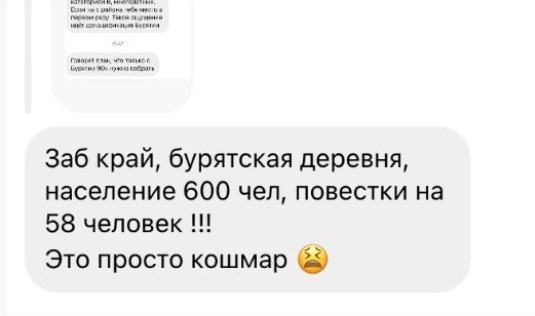

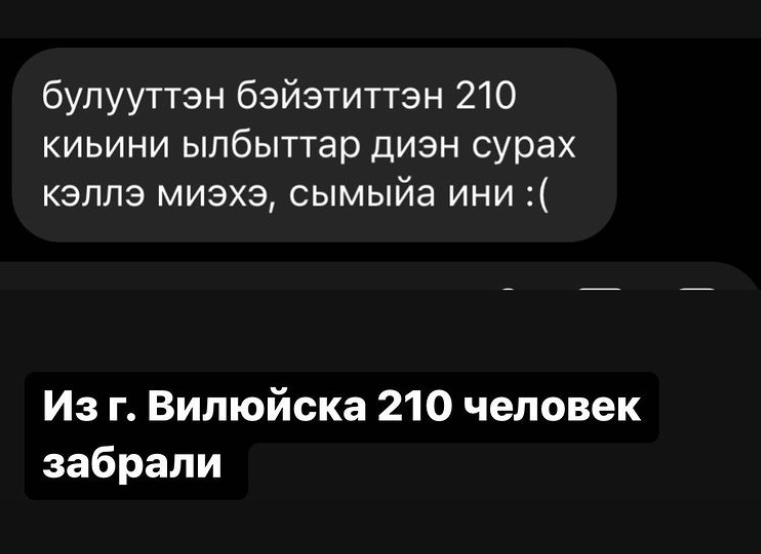

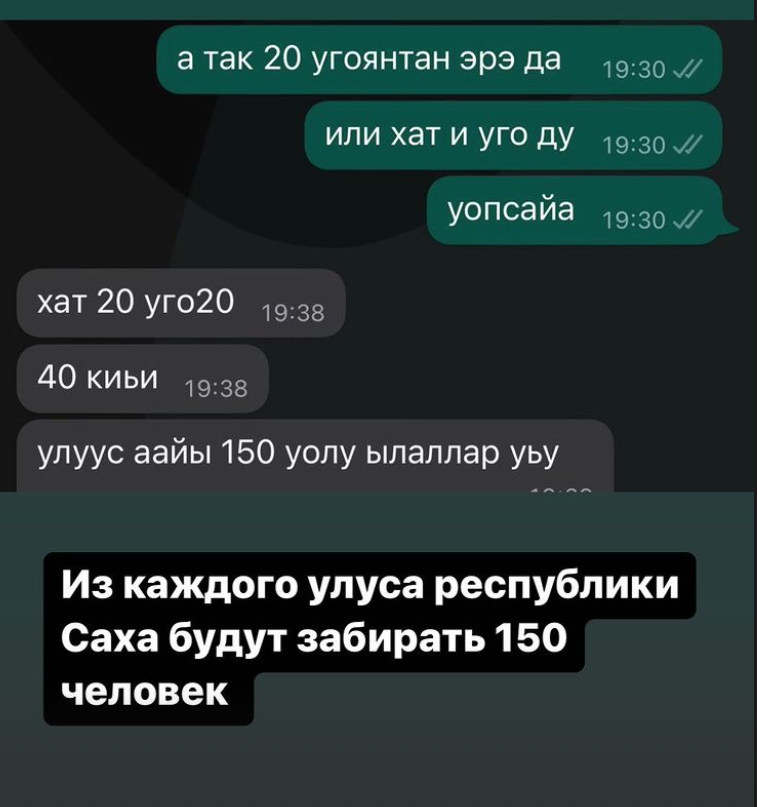

On Wednesday, September 21, 2022, following severe setbacks in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, President Putin announced an immediate “partial mobilization” of Russian citizens, which means citizens on reserve (men who have served their mandatory conscription terms or have deferred service) will be called up and those with past military experience will be conscripted. This is Russia’s first draft since the Second World War. Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu announced that Russia plans to call up 300,000 reservists. Since then, thousands of people have been arrested at anti-mobilization protests across the country, one-way tickets from Russia to Turkey and other countries that do not require entry visas for Russian citizens have sold out, and questions about who will escape the draft and who will be forced to fight become even more pressing. People in the “ethnic republics” already know what the probable answers to these questions are. The social media accounts of anti-war campaigns and organizations are brimming with information on how to potentially avoid the draft and anecdotal evidence submitted by individuals witnessing men receiving draft notices and being collected from their homes in the middle of the night and from universities and colleges. Military registration employees and enlistment officers are allowed to deliver summons to people’s places of residence and at their place of employment since, by law, employers are obligated to help military commissariats.

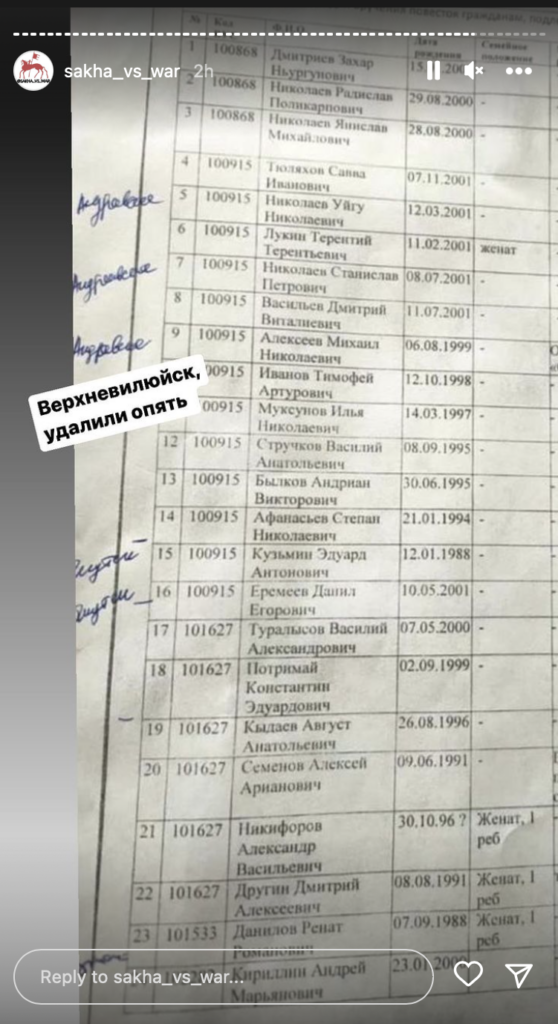

Additionally, lists of names of people who will potentially be drafted are circulating, with the hopes that the individuals listed can evade conscription.

Third column contains names, fourth column birth dates, fifth column contains information about spouse and children.

Though the exact numbers of draftees from “ethnic republics” is unknown, significant numbers are already being rounded up. Since much of the information about the “partial” mobilization is coming from various anonymous and nonsystematic sources and organizations do not have the time to thoroughly vet or process it, the Free Buryatia Foundation created a Google Form to help gather analytics, which are “more important now than ever [as] we need to understand how many people have been mobilized”. Video and anecdotal evidence from across Russia demonstrates large drafts taking place even in small villages and towns. Footage from the Sakha Republic appeared to show dozens of men being collected at the soccer stadium and loaded on buses headed to recruitment centers. These direct messages, photographs, videos, and documents suggest that the proposed summoning of 300,000 men will in fact be higher. Failure to appear at the military enlistment office after being subpoenaed results in a warning or administrative fine from 500 to 3 thousand rubles, according to Article 21.5 of the Administrative Code. However, new legislation hurriedly passed by the State Duma on Tuesday, September 20 sets new, harsher penalties for those who attempt to evade service, surrender, or refuse to fight. Individuals with wealth or connections might be spared from military service or potentially have the means to flee the country which underscores how men from largely impoverished regions are more likely to be fighting in the war.

Support for the war voiced by Indigenous-majority republican leadership, cultural organizations, and individuals is categorically and significantly ironic as it goes against the interest of the country as a whole, and of Indigenous Peoples specifically. Russia’s war on Ukraine is a colonial effort on two fronts, committing a double genocide as it continues its unlawful invasion and violent destablization of Ukraine while using Russia’s Indigenous Peoples as cannon fodder.

Anti-War Initiatives Led by Indigenous Peoples in Russia are Inherently Anti-Colonialist

Anti-war movements in Russia immediately appeared at the onset of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Notably, these initiatives were and are by and large driven by preexisting feminist organizations (The Social Democratic Alternative, Eighth Initiative Group, Eve’s Ribs, the Agasshin Project, and the Feminist Translocalities Project to name a few) and Indigenous and ethnic minority groups founded in direct response to the war. While currently there is no sole, centralized movement uniting the country’s numerous Indigenous Peoples and ethnic minorities, the appearance of various anti-war organizations, media accounts, and content, and action points to a rather unprecedented impetus of collaboration and solidarity focused on condemnation of the Russia state’s actions.

Further unparalleled is the overt and widespread presence of anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist sentiment as activists and laypeople alike criticize Russia’s attack on Ukraine and probe into the federation’s enduring issues of coloniality in quotidian life (racism, discrimination, xenophobia, and the violence they encourage). The invasion of Ukraine is not new or covert; rather, it represents the next steps in a long and ongoing history of Russian colonial understanding of a sovereign Ukrainian nation and distinct Ukrainian culture as a threat needing mitigation. These anti-war, staunchly anti-colonialist, and Indigenous-led initiatives are small in number but increasingly outsized in influence. From the use of native languages in anti-war campaigns to overt castigation of Russian chauvinism, these initiatives point to resistance to both the ongoing war and colonial policy. Their importance cannot be overemphasized since their efforts contribute to a better understanding of, and subsequently, better capacity for dismantling Russian coloniality.

Russia’s claims that it is fighting “neo-Nazis” in Ukraine is a blatant distortion of history, and the irony of this claim is far from lost on many Indigenous Peoples of Russia who grew up in a society steeped in Russian colonialism and who witness growing ethnic Russian nationalism (often abetted by right-wing and neo-Nazi sentiment) on societal and institutional levels (e.g., ethnic Russian nationalism enshrined in the federal constitution since 2020).

Anti-war movements like the Free Buryatia Foundation––the first anti-war initiative started in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and on behalf of an ethnic group––emphasize this paradox and use the current conflict to advocate for a reckoning with historic racism and imperialism within Russia’s own borders. The objective of The Free Buryatia Foundation (Buryats Against the War) is twofold––to fight against the war on Ukraine and to “solve the problem of racism and xenophobia in Russia”. Founder and president of the fund, Alexandra Garmazhapova, says such an organization was needed for a number of reasons: the disproportionate number of Buryat soldiers dying in the war, the overrepresentation in media of Buryats as the main perpetrators of violence, and the latent systemic factors that usher Buryats into military service.

“Our region has been the leader in losses since the very beginning of the war, and it was important for us to declare that we are Buryats, and we are against the war. We consider the war with Ukraine xenophobic, because if Russia had a tolerant society, the idea of ‘denazification’ of Ukraine…would not find support among Russians. The Indigenous Peoples of Russia have been and are being subjected to ‘denazification’, which in reality is complete Russification. We understand what it’s like to have your language and culture banned… Residents of ethnic republics who go to Moscow and St. Petersburg face xenophobia and racism… But at the same time, military personnel from [the ethnic republics] are sent to Ukraine to protect the ‘Russian world’,” Garmazhapova said in an interview in July.

The Free Buryatia Foundation tracks statistics on losses during the war, provides legal advice to help military personnel terminate their contracts, shares credible information to combat propaganda and misinformation, and strives to prevent Russian servicemen from going to Ukraine. The organization is very active on social media sites and regularly collaborates with specialists, activists, and other anti-war initiatives on live-streamed discussions, data collection and sharing, and crowdsourcing.

Most of the Free Buryatia Foundation’s team resides outside the Russian Federation, which shields them from Russia’s growing restrictive legislation, namely “fake news” laws, which criminalize the dissemination of false information about the Russian army and is used by the state to censor, detain, and imprison those who oppose the war. For that reason, there are no large-scale Indigenous-led anti-war organizations or groups based in Russia. Disparate groups and media accounts exist though they tend to maintain anonymity and much of their activism work is shared or takes place on Instagram (only accessible with use of a VPN) and Telegram. These include, but are not limited to the Sakha Pacifist Association, New Tuva Movement, and Asians of Russia (which existed prior to the war but shifted its focus to information about the war and protests), which share information specific to their respective regions in addition to sharing information among each other.

Indigenous individuals are actively engaged in anti-war actions though they are targeted by the Russian Federal Security Service and the Center for Combating Extremism (unit in the Ministry of Internal Affairs). The social media pages for various groups often crowdsource funding these activists need for legal aid. While the groups are not organized or affiliated, through their sharing of each other’s posts and through collaborations, they’re forming a kind of network––one that is able to exist under the current Russian state. Through posts on social media are seemingly low-impact, these groups are harnessing social media as a tool to disseminate information restricted by the state and state-run media and building networks on platforms that are relatively accessible.

There is no single position towards the war among Russia’s different Indigenous groups. These groups are often asked how individuals, who carry out demonstrations with signs saying “Tuvinians against the war”, or nameless admins, by using names such as Sakha Pacifist Association or New Tuva Movement, are able to speak for an entire people group. “These action[s] raise the rebellious spirit of the people. [They’re] very important demonstrations and actions for the entire people, as well as a message to the whole world,” wrote sakha_vs_war. The evocation of one’s nationality or cultural background is yet another tool for appealing to the public. The state and regional governments also utilize this tool in their co-opting of national cultures broadly, and of organizations such as the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) and the Buddhist Traditional Sangha Center of Russia specifically, in support of hostilities against Ukraine. Identity, language, and culture are effective tools for anti-war movements in this particular case as initiatives consistently underline the imperial nature of this current war.

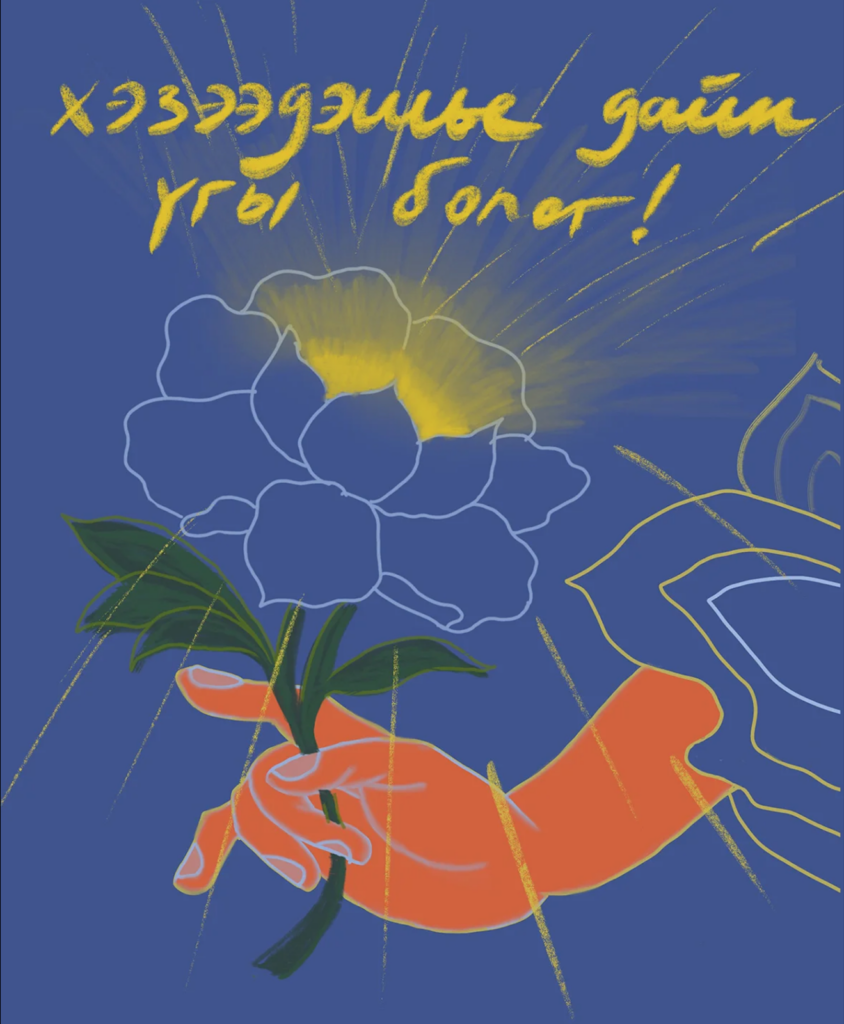

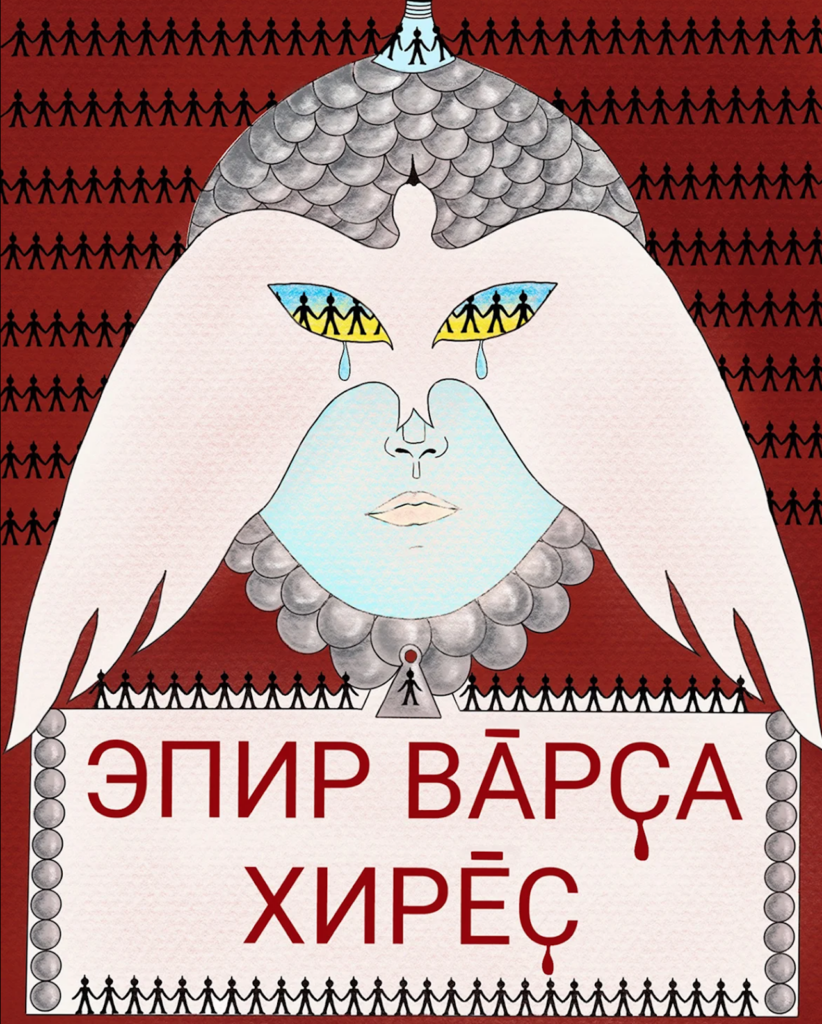

Given Russia’s history and continuing legacy of colonial language policy inherited from the Russian and Soviet empires (which systematically afforded/s primacy to the Russian language at the expense of native languages), anti-war slogans in Indigenous languages are part of reclamatory cultural education which is, at its core, anti-war as it is a struggle against colonialism. The struggle around national languages in Russia is inextricably tied to state-sanctioned xenophobia and Russian supremacy. State language policy has become increasingly restrictive on native language education as Putin proclaimed in 2017 that Russian “the natural spiritual framework of the country” and that “everyone should know it”. Then, in 2018 three amendments were made to Law No. 273 “On Education in the Russian Federation,” which made Russian language learning compulsory at the expense of native languages. National or republican sovereignty movements of non-Russian, and overwhelmingly Indigenous, ethnic groups are thus intimately intertwined with language and cultural sovereignty, making language and culture significant areas the state and its security forces carefully scrutinize. Therefore, with this context, struggles for regional authority or autonomy and the anti-war struggle are innately linked.

For many activists, printing and disseminating anti-war messages in Indigenous languages is not only symbolic of the resistance against the colonial Russian state, but also a rallying call to compatriots who might support the war or who do not openly oppose it. The Agasshin Project published a series of anti-war posters in Indigenous/national languages created by speakers of the languages (Buryat, Kalmyk, Udmurt, Chuvash) since anti-war activities in Indigenous languages “can be instruments of resistance to both the current war and colonial politics”. Aikhal Ammosov, a Sakha musician and activist, has been tried twice and is awaiting a third trial for his anti-war picketing and performances in Sakha, Russian, and English. Ammosov was first fined for “hooliganism”, then for “discrediting the Russian armed forces”, and he currently awaits trial and could possibly face up to three years in prison for his most recent art performance involving a banner reading “Yakutian Punk Against WAR”.

Following Russia’s February 24, 2022 invasion of Ukraine, activists around the world began publishing texts about colonialism, racism, and violence in Russia with fervor. Though these activists and groups are far from monolithic and cater to regional, historical, and culturally specific needs, these ideas spread and grow horizontally across the sphere of Russian influence, allowing for grassroots collaboration, collectivization, and support to grow.

Ethnic Minorities Hit Hardest By Russia’s Mobilization, Activists Say

Just hours after Russian President Vladimir Putin announced a partial mobilization for the war in Ukraine last week, a family in Russia’s majority-Buddhist republic of Kalmykia gathered to decide how to protect its four draft-eligible men.

“We thought my uncle would be drafted first and decided he would go to Kazakhstan… He left the next day,” the youngest man in the family from Kalmykia’s capital Elista told The Moscow Times.

Assured that his family was relatively safe, the man — a local activist who requested anonymity to speak freely — started helping conscription-age men to avoid “becoming cannon fodder” by fleeing abroad. But then his father received draft papers.

“I wasn’t able to convince my father to leave… I am going to the draft office tomorrow to bid farewell,” the activist wrote on social media Thursday.

“He is 47. He avoided the Chechen war, but not this one.”

Evidence from regional activists who spoke to The Moscow Times suggests that, almost a week into Russia’s mobilization drive, a disproportionate amount of the men being drafted come from Russia’s ethnic minorities.

Many of the ethnic republics that appear to have seen large numbers of men receiving draft papers — including the North Caucasus republic of Dagestan and Siberian republic of Buryatia — have already suffered heavy losses in the war in Ukraine.

“In Elista, they are planning to take 332 people, which is quite a lot for a city with a population of no more than 150,000,” local Kalmyk activist Daavr Dordzhin told The Moscow Times.

In the Siberian republic of Buryatia, one of Russia’s poorest regions, thousands of men — including recently discharged soldiers and those who initially refused to be sent to Ukraine — have apparently received call-up papers.

“All the young men we were able to save and bring back home are now being invited to go back into that meat grinder,” said Alexandra Garmazhapova, co-founder of the anti-war Free Buryatia Foundation that helps conscientious objectors.

There are no official figures for the numbers of men mobilized in each Russian region, and The Moscow Times was unable to confirm numbers given by activists.

In Bashkortostan, an oil-rich Muslim-majority republic in central Russia, fathers of four and men over 40 years old are among those to have received draft papers, according to Bashkir opposition activist Ruslan Gabbasov

“I don’t know the exact numbers of people drafted, but they are sending out draft papers left, right and center,” he told The Moscow Times.

And in Crimea, which Russia annexed from Ukraine in 2014, the peninsula’s indigenous Crimean Tatars have apparently been hit particularly hard.

“Eighty percent of the draft papers for mobilization in Crimea were sent out to Crimean Tatars (Crimean Tatars make up less than 20% of the population of Crimea),” journalist and activist Osman Pashaev wrote in a post on Facebook last week.

Many activists have suggested mobilizing more men from ethnic minorities far from Moscow and St. Petersburg is a way for the Kremlin to reduce the draft’s impact on major cities, where the chances of opposition protests are higher.

But many of these regions — which are generally poorer and more fertile recruiting grounds for the Russian army that can provide a stable salary and act as a social lift — also have a higher-than-average number of military veterans.

“A mobilization that focuses on recent veterans will… disproportionately affect regions where there are more military units,” military analyst Rob Lee tweeted last week.

Perhaps because of the outsize impact of the draft on their communities, ethnic minorities have played a prominent role in anti-mobilization protests — often led by women — in recent days, with videos emerging of demonstrators blocking roads, scuffling with police and calling for peace.

The ethnic republics of Dagestan, Kabardino-Balkaria and the Arctic republic of Sakha all saw significant protests over the weekend.

Demonstrators in Yakutsk, the capital of mineral-rich Sakha, organized traditional dances at a protest Saturday and were seen chanting “No to war!” and “No to genocide!” — a reference to the fact that mobilizing men from small ethnic minority communities will likely cause their population numbers to plummet.

And in Dagestan, protesters in the town of Khasavyurt blocked a key highway Sunday. Police fired in the air in an attempt to despers the rallies, according to videos from the scene.

Over 10 times more people were detained at anti-mobilization protests Sunday in Dagestan’s Makhachkala than in Moscow, according to protest monitoring group OVD-Info.

Like in most Russian regions, the mobilization drive in ethnic republics appears to be particularly intense in poorer, rural areas, activists said.

In the Caucasus republic of North Ossetia, “draft papers are distributed mostly in villages,” one local activist who requested anonymity told The Moscow Times.

And a similar tactic is used in Bashkortostan.

“They are taking ordinary boys from the districts and villages,” one eyewitness from Bashkortostan said in a message sent to the Free Buryatia Foundation that the group subsequently shared online.

Many activists blamed regional leaders keen to impress the Kremlin for the speed of mobilization in areas with large ethnic minority communities.

“The over-eagerness of the head of Buryatia, Aleksei Tsydenov, plays an important role,” activist Garmazhapova told The Moscow Times.

“If Vladimir Putin told him to do a pole dance, he would do it. And just as easily he will send young men from Buryatia to war… He doesn’t see them as people, he sees them as a means to achieve his [political] goals,” she said.

Mobilization. Appeal of the International Committee of the Indigenous Peoples of Russia to the indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East.

Brothers and sisters!

On September 21, President Putin announced a “partial mobilization” in the country. Nobody can be fooled by the word “partial” today. There have been already numerous evidences that summonses are being handed to thousands of future soldiers whom the Russian government has decided to throw into the furnace of war. Young people, middle-aged men and even those who are almost 50 years old, are massively taken away from work places, even at night, separated from relatives and friends in order to be sent to fight for Putin’s wealth. This way he and his gang could continue to rob Russia unhindered, frightening Russian citizens and peoples from neighboring countries.

Putin has been caught lying more than once. After the invasion of Ukraine began, he said that everything was going according to plan. But why do we need such an urgent and sudden mobilization then? The Ministry of Defense stated that the losses of the Russian army are small. But why do they need hundreds of thousands of soldiers more? The truth is that the Russian army is suffering huge losses, and you don’t hear about it on TV. That’s why Putin and his generals urgently needed a new “manpower”.

Today, many lackeys and propagandists tell you that it is everyone’s sacred duty to defend the fatherland and that Russians are happy to go to the front as volunteers. But this is also a lie. No one threatened Russia with war until the Russian army invaded Ukraine, and all those who really wanted to fight have long had the opportunity to go to the front as volunteers. Putin has begun forced mobilization in order to be able to send to death new hundreds of thousands of those who do not want to die voluntarily in the name of his in the name of his paranoid goals.

Everyone knows the horrible level of corruption in Russia. Those who have money, connections, influential relatives, will easily buy off military service. The poor will go to war, those who will not be able to give a bribe, buy a medical certificate, and urgently enter the university. We all know that indigenous minorities are one of the most disadvantaged groups in the country. Today, officials of the State Fishing Agency and hunting inspectors force our aborigines to pay bribes. Tomorrow, military enlistment offices will force the same people to pay bribes again.

In these conditions, the position of the so-called “leaders” of the associations of indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East, who continue to praise Putin and his policy of destroying the population of Ukraine and sending more and more recruits to war, is especially shameful and vile.

We all want peace and a quiet life. We all want our hunters, fishermen, reindeer herders to stay alive and continue the traditions of their ancestors, and not perish in a foreign country at the behest of Putin. Therefore, we appeal to you, brothers! Sabotage the orders of your superiors. Burn military Ids. Throw out summons to the military. Don’t show up at recruiting stations. Surrender to the Ukrainian side as soon as you get to the front. This way you will save yourself for your families and your indigenous communities.

We also appeal to you, sisters! Do not let your husbands, brothers, fathers go to war. Spoil documents, do not answer calls from military commissariats. Do not believe the promises of the authorities and the military that they will return your loved ones alive. Do not believe that the authorities will pay money for the deaths and injuries of your relatives. They will cheat again, and you know it. This war unleashed by Putin and his clique is an unjust war. This war is not for Russia and its future, this war is for the continuation of the plundering of the citizens of Russia, its peoples. This war unleashed by Putin and his cabal is an unjust war. This war is not for Russia and its future, this war is for the continued plunder of the citizens of Russia, its peoples. This war is the killing of innocent people, citizens of Ukraine, women, children, old people.

Don’t participate in this war. This is not our war!

A Just Transition = Indigenous Self-Determination

Tuesday, September 20, 2022

The People’s Forum 320 W 37th St, New York, NY 10018

Galina Angarova (Buryat), Cultural Survival Executive Director

Pavel Sulyandziga (Udege) Chairman, Batani Foundation

Event by: Cultural Survival, Batani Foundation, First Peoples Worldwide, Earthworks, Society for Threatened Peoples, A Growing Culture

Transition is inevitable. Justice is not. The push for a sustainable transition predominantly centers “green” technologies that continue to threaten the self-determination and sovereignty of Indigenous peoples worldwide. Instead, a just future depends on centering Indigenous-led, place-based climate solutions and supporting intersectional efforts to guarantee the rights of all people.

Join the Securing Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in the Green Economy (SIRGE) Coalition and A Growing Culture to learn about how Indigenous and peasant leaders are taking action to hold companies accountable to human rights commitments through the supply chain.

Performances by Pavel Sulyandziga Jr. (Udege)

Refreshments will be served.

THIS IS A HYBRID EVENT: In-person (space is limited) and virtual.

Translation into Spanish will be available via zoom.

Co Sponsors: Cultural Survival, Batani Foundation, First Peoples Worldwide, Earthworks, Society for Threatened Peoples, A Growing Culture Date: September 20, 2022 Time: 11:00 am-2:00 pm EST Location: The People’s Forum 320 W 37th St, New York, NY 10018 also virtually acessible via zoom.

Xenophobia and indigenous peoples in Russia. What does the “Hate Crime” topic mean for Russian IP?

Presentation for the OSCE Expert Meeting “Addressing Hate Crime against Indigenous Peoples” by Dmitry Berezhkov.

The “Hate Crime” topic regarding indigenous peoples is still relevant for Russia. It is a great challenge that has roots in colonial history and the colonial nowadays of the ultimate nature of the Russian Empire, then the Soviet Union and today’s Russia, which has similar origins to the colonial suffering of other indigenous peoples around the world. So I will not touch today on the history of the issue in Russia as it is very similar to the history of other indigenous peoples whose lands were colonized by other nations.

The topic “Hate Crime” was very relevant for Russia in 2000 when we received every year messages about killings and beatings of indigenous students by skinheads in Russian capitals, Moscow and Sant Petersburg. That was dozens of killings, many of which were not reported as “hated crimes” because, for police, it was more comfortable to consider them domestic crimes.

It has to be said that it was not directed against indigenous peoples but against every person whom Russian far-right radicals consider “others”. Primarily against people with Asian appearance as persons from the Caucasus could fight back roughly.

And Russian authorities at those times demonstrated evident efforts to fight against skinheads. Police arrested some of their leaders; authorities tried to control football fans’ organizations, one of the primary sources of skinheads activity. But the main milestone of reducing skinheads activity became 2014 when president Putin was able to trick the situation and refocus the hatred of the Russian far-right radicals against Ukraine, the US and NATO after the annexation of Crimea.

At the same time, domestic intolerance and xenophobia continue to be one the main features of indigenous peoples’ living, especially in urban and industrialized areas.

In a short presentation, I will not concentrate on this topic but need to mention the problem of keeping indigenous children in boarding schools. Formally these schools are organized for children from every family. Still, in practice, in remote villages of the Russian Arctic, Siberia and the Far East where indigenous peoples live, mainly children from indigenous families live in such boarding schools.

Besides the problem of assimilation, losing the native languages and traditional culture, the challenge of domestic intolerance against indigenous children by personnel of such boarding schools is still actual for many Russian regions. We were reported that indigenous children were beaten by boarding school personnel in Novy Port village (Yamal) in 2019. In another boarding school (Beloyarsk village, Yamal) in 2019, the director organized an illegal hotel for migrant workers who lived just in neighboring rooms with children. In 2021 in the boarding school in the village Polunochnoe (Sverdlovsk region), indigenous children who adapted to traditional food did not like the unusual for them boarding school cuisine. But when one of the personnel supported by indigenous parents tried to raise this issue in the media, the boarding school fired the person and wrote a statement against her to the police.

In some cases, local informants provide us with information that the municipal administration specially put indigenous children not in usual schools but in boarding schools to keep state finance from Moscow for the municipal budget. In other cases, we were reported that boarding school personnel didn’t fight against bullying but participated in it.

These examples show that domestic intolerance regarding indigenous peoples is still a problem for Russia until nowadays.

At the same time, I want to highlight another aspect of xenophobia closely connected with the rights to lands, resources and self-determination. Today these continue to be the hottest challenge for the Russian indigenous peoples’ development. As you know, Russia is a world producer of natural resources. Yet, Russian businesses closely connected with authorities through corrupted links try to use any opportunities to press out indigenous communities from their traditional lands.

I will give you an example. Some years ago, in my homeland region Kamchatka, the speaker of the regional parliament, Boris Nevzorov, implemented the legislative act that had to exclude South Kamchatka from the federal list of indigenous traditional lands. We have such a list of territories in Russia, and only indigenous peoples who live in these territories have some rights to traditional fishing, hunting and other traditional livelihoods. At the same time, a lot of indigenous traditional lands where indigenous peoples continue to live were not included in this list.

So Boris Nevzorov prepared the rationale for this law. In this document, he noted that only a small percentage of indigenous peoples live in these territories – less than 5 percent of the total population. He based on the history that during the Soviet times, the South of Kamchatka as most comfortable for living area was intensively industrialized by authorities (so he put the historical colonization as a justification for future one). There were also many other unnatural arguments, including that indigenous peoples’ traditional fishing threatened national security as the South Kamchatka is a base for the Russian Far East nuclear submarines fleet, and American forces could use the indigenous peoples to raise separatism in Kamchatka. This is a nonsense for us or any sane person, but this is a reality of Putin’s Russia.

But the reason why Nevzorov tried to exclude these lands from the federal list of indigenous territories was straightforward. While he is a Russian official and represented legislative authorities, he, at the same time, was an owner of the biggest Kamckatka fishing company, “Ustkamchatryba,” and tried to exclude indigenous communities as competitors for access to fishing resources. It must be noted that Boris Nevzorov is officially one of the reachest Russian state officials.

After he failed to lobby this legislation in Moscow, which we tried to block with all efforts, he started an information campaign in local media. In this TV show, journalists asked ordinary Kamchatka residents what they think about the law, according to which only indigenous persons in Kamchatka have the right to fish free without a license. Of course, this is a tiny amount of fish per year – about 50 kilos, but for the poor Kamchatka population, even such an amount is substantial.

The question was formulated like this: “Indigenous peoples in Kamchatka have the right to fish salmon without licenses while others who live in Kamchatka for many years or maybe their whole life have no such right. Do you think it’s fair?” I will not explain how chauvinistic further discussion this question followed by.

And this is a trick used by business and state officials regularly in Russia to continue to control indigenous lands and resources.

I would be able to give you many other examples of intolerance, xenophobia and chauvinism towards indigenous peoples in Russia. It is dangerous when such cases continue to happen in any state. It is very dangerous when the state does not fight against xenophobia. But it is extremely dangerous when the state canalizes xenophobia in a politically or economically beneficial way for state powers.

Now Putin canalizes the energy of the Russian nationalists against Ukraine. What target will be next? We don’t know.

I think international institutions like OSCE have to rethink their approaches to democratic discussion with totalitarian states like Russia regarding human rights, whether it is indigenous peoples’ rights, hate crimes or any other human rights.

30 August 2022, Vienna.

After a 6-month Arctic Council pause, it’s time to seek new paths forward

As the war in Ukraine drags on, Arctic states need to find more permanent avenues for collaboration in the region.

The Arctic was supposed to be exceptional — an area of the globe substantially removed from the pressures of great power politics. Russia and the U.S., despite their military and security interests there, found ways to cooperate regardless of troubles elsewhere. The Arctic Council in 2021 celebrated its 25th anniversary as a successful forum for cooperation on economic and environmental issues among the eight states with territory above the Arctic Circle.

Then came the Russian invasion of Ukraine earlier this year, which dealt a long-term blow to regional harmony.

It has been six months since the work of the Arctic Council was put on hold by the U.S. and other members besides Russia. The most important venue for pan-Arctic cooperation — and thus a central element of Arctic cooperation itself — ceased to function for the first time. As the Ukraine conflict shows few signs of winding up, it is time to take stock of where we are and what the future paths for Arctic relations may be.

The pause initiated on March 3, 2022 by the seven so called “A-7” or “Arctic 7” states was by its terms supposed to be temporary, with participation in Arctic Council activities hopefully to be resumed pending improved circumstances. When conditions didn’t improve, on June 8 these states announced a limited resumption of work on council projects that do not involve Russia’s participation. While such projects account for a substantial amount of work, the step was awkward given that Russia holds the council’s two-year rotating chairmanship and was leading the council’s efforts.

The invasion of Ukraine had a deep impact on the U.S. and Western countries in particular, and it could not be ignored in the Arctic. It brought war to the heart of Europe, and led many countries including Arctic Council member states to provide arms to Ukraine that are being used against Russian soldiers. In the Arctic, Russia became widely seen as a not just a theoretical but an active threat, with the result that Finland and Sweden took the extraordinary step of applying for NATO membership. As a result, NATO will increase its northern (and thus Arctic) presence, and all Arctic nations besides Russia will be NATO members — a disquieting development for Russia. The council — and other Arctic institutions and processes — had muddled through Russia’s attack on Crimea, but this was more serious.

What has become clear is that the degradation in Arctic relations will be with us for the long term. Where does that leave us?

Multilateral Arctic cooperation is more necessary than ever. The latest science informs us that the Arctic is warming four times faster than the rest of the globe (not just two to three times faster as thought until quite recently), and seven times faster in some areas. Circumpolar science conducted in the Arctic is vital for addressing climate change worldwide.

The Arctic Council has made a tremendous contribution on a wide range of environmental and economic issues, and its programs need to be continued and strengthened. It has taken years for the council to develop into an effective organization, and its collapse needs to be avoided because Arctic residents and stakeholders have come to depend on it. Rebuilding the institution could be time consuming and difficult.

Yet, working with Russia in the Arctic Council isn’t appropriate or feasible at the moment. The council isn’t a regulatory body that produces rules for governance the way the International Maritime Organization does for shipping or the International Civil Aviation Organization does for air traffic. It is a forum that achieves its objectives on the basis of discussions and mutual accommodation. Governments at odds over Ukraine can’t be expected to make progress on environmental rules where trust is needed, or to jointly promote business opportunities.

Indigenous groups have insisted that Arctic collaborations must continue despite the war in Ukraine, to find ways to improve health conditions, promote adaptation to a changing environment and improve infrastructure and living standards. They point out, with considerable justification, that the needs of their communities have little to do with the crisis in Ukraine or geopolitical rivalries.

It is important to bear in mind that aspects of Arctic multilateral cooperation not involving Russia remain robust and effective. There are strong economic and science links among the other Arctic states, as well with non-Arctic states active in the region, that in no way depend on Russia. These are ongoing and are not necessarily impeded by the Arctic Council being sidelined or by lack of access to Russian territory or support.

And yet, in the long term, there is no meaningful pan-Arctic cooperation without Russia. It makes up about half the Arctic, and is a country not only of considerable size but also influence and capability. Hence, it is necessary to keep in mind and indeed hope for the eventual reintegration of Russia into systems of Arctic cooperation, including the Arctic Council.

With all this in mind, what are the next steps that the U.S. and allied countries should take?

The A-7 countries moving ahead with Arctic Council on projects not involving Russia made good sense, but doesn’t deal with the more fundamental question of the status of the Arctic Council itself. Should the council, even in the midst of the Russian chairmanship, be taken over by the other members and operated without Russia?

I believe this should be avoided. The basic concept of the council at its creation is that it was a body comprised of eight states with equal status, and that all decisions would be taken by consensus of the eight. This was a fundamental aspect of the 1996 Ottawa Declaration. As the council is a forum and not an international organization as a legal matter, there is no breach of international law if the A-7 decide to ignore the consensus rule and in effect jettison Russia. But that would be inconsistent with the declaration and the rules of procedure of the council, and Russia is likely to object strenuously. The council would face difficult procedural problems. The work of the council’s subsidiary bodies are supposed to be endorsed by the Senior Arctic Officials and by ministers who would meet in May of next year. However, Russia is slated to host the next ministerial, and it isn’t clear how or when a ministerial without Russia could be convened, or how Norway, as the incoming chair, would have its proposed work program agreed by ministers.

Thus, if the Arctic Council is operated without regard to Russia during the Russian chairmanship, or if the other countries host their own ministerial or begin a new Norwegian chairmanship without Russian concurrence, it becomes more likely that Russia would resist returning to the Council in the future. Russia has already withdrawn from the Council of the Baltic Sea States and the Council of Europe, and so as has been suggested elsewhere, “the danger is real.”

A possible way to avoid this problem is for the A-7 and Indigenous groups to agree to interim measures under which they would continue Arctic cooperation, both Arctic Council projects not involving Russia and other forms of cooperation that they wish to undertake as a group, without formally doing so under the banner of the council. They could, at least as an initial step, agree to follow the procedures of the council as appropriate and continue to receive support from the Arctic Council’s secretariat located in Tromsø, Norway.

In pursuing any course of action, there needs to be active consultation with the Indigenous groups who would normally wield considerable influence within the Arctic Council. That said, the solution is unfortunately not as simple as inviting all the Permanent Participants, as these groups are known within the Council, to join in a collaboration with the A-7 states, as one of them, the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (or RAIPON), has taken a formal position supporting Russia’s Ukraine invasion. Including RAIPON would likely not be acceptable to the A-7.

Beyond the diplomacy that takes place in the Arctic Council, the A-7 and their allies need to pay increased attention to Russia’s military buildup in the Arctic. Contact between their coast guards and Russia’s remains important, along with attempts to establish and implement protocols that reduce the risk of accidental conflict on the sea and in the air.

In addition, the stoppage within the council presents non-Arctic states with an opportunity to work more closely with the Arctic states. This will be true for the A-7 states, which can increase their collaboration with actors such as the EU, the UK, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea on economic, scientific and security matters. But in parallel we can expect that Russia will reach out to China and India, to involve them even further in Arctic affairs.

It turns out that Arctic exceptionalism was a mirage. Nevertheless, while we can hope that the Arctic Council will regain its footing in future years, as the Ukraine crisis continues, the U.S. and other Arctic countries should search for other ways to promote Arctic cooperation.

Recognizing the transformational potential of Indigenous-led conservation economies

Over the last decade, Canada has seen an increase in the number of initiatives to green or circularize the economy through sustainable development, as well as those that support and enhance Indigenous environmental leadership.

Both projects are desperately needed given our rapid progress towards capitalist-driven climate catastrophe. Although there is interest in creating new economic systems, Canada is failing to recognize the transformational potential of Indigenous-led conservation economies.

These economies have immense reconciliatory potential and need to be respectfully supported and engaged with in order to create new shared and equitable economic systems.

Environmental management is not just ecological. All social and economic drivers require respect for earth, water and animals in order to halt degradation and enhance environmental and human health.

Canada’s commitments

In September 2015, Canada along with every other United Nations Member States adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Seventeen action categories were identified with the purpose of “leaving no one behind” and with the goal of bringing everyone in Canada up to a level of economic stability connected to overall environmental health.

In November 2021, Canada then established a target to protect 30 per cent of the country’s lands and oceans by 2030.

Alongside this announcement was a recognition of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCA). They have been dubbed “territories of life” functioning as ecosystem networks in traditional territories. They are Indigenous-led and represent a long-term commitment to conservation that elevates Indigenous rights and responsibilities.

These IPCAs have also become generative sites for Indigenous economies, with the potential to influence real change in economic development practices.

The processes and activities which contribute to Indigenous-led conservation can be referred to as environmental stewardship practices. Indigenous people generally take a holistic approach to the stewardship and management of their territories which has resulted in harmony with the land and sustained biodiversity conservation.

Understanding how stewardship produces values beyond monetary ones, can create vital learning opportunities for alternatives to conventional development.

New enterprises and environmental management

Guardians and Watchmen enterprises are two forms of Indigenous environmental stewardship. In both cases, cultural values are respected and utilized to create new enterprises and environmental management systems.

In Kitasoo Xai’Xais on the central coast in British Colombia, community leadership has created a robust tourism program through the Spirit Bear Lodge and Coastal Stewardship Network. There, community members are employed to steward their traditional territories, becoming guides for tourists and sharing their knowledge and experiences within their unique coastal region.

These reciprocal economies are not based on the creation of private wealth. First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities across Turtle Island are pursuing sustainable development by investing in clean energy transitions, working as scientists to support ecosystem research, creating regional conservation partnerships and advocating for our shared habitats through collective movements.

Diversifying our understanding of economies

Amidst louder calls for Indigenous Peoples’ free, prior and informed consent — which means Indigenous people need to give or withhold consent to a project that may affect them or their territories — on land-intensive development proposals, decolonial movements like #LandBack and various projects to diversify our understanding of economies have taken root.

A recent article by geographers Lindsay Naylor and Nathan Thayer investigates how power operates when considering decolonial and anti-racist solutions as a necessary evolution of diversifying our economies.

In the article they explore how the diverse economies framework “neglects the theft and occupation of land that unfolded over the previous centuries of colonialism, which fundamentally changed people’s relationships to the land.”

In settler-led economic development systems, conservation is considered an external feature to be managed by capital investment projects and philanthropic activities. They propose flipping the script and paying close attention to the voices and actions of Indigenous Peoples who can offer some much-needed guidance.

The authors of a recently published Yellowhead Institute paper, Cash Back, write:

“The multiplicity of Indigenous economies is not a future prospect: it is already here … At their core, what makes them Indigenous economies is that they do not exploit that which they depend upon to live, including people. And they protect a world that is not prepared to value people’s time, homelands and harvests solely in cash.”

Moving forward

New conservation-based economic developments in the blue economy, the project finance for permanence — which gives permanent and full funding to conservation areas — and regional conservation finance actions are excellent examples of how Indigenous knowledge and voices are beginning to influence the way national development policies are informed.

These plans and programs involve diverse perspectives on how to pursue economic development which can be thought of as “parallel rows,” knowledge systems stemming from distinct settler and Indigenous knowledge systems.

This parallel row idea comes from the Two Row Wampum treaty which represents the peaceful and respectful coexistence of two distinct nations.

The brilliance of this term lies in its ability to propose a joint system where both Indigenous and settler perspectives are self-directed and complementary in collaboration without having to be integrated together. A resurgence of Indigenous autonomy and culture is a key feature of this strategy.

We may all learn from Indigenous Peoples’ continuous collective efforts to shift away from settler-based models of accumulation and toward maintaining and developing healthy economies of abundance.

U.S. to appoint Arctic ambassador in sign of region’s growing importance

The Biden administration announced Friday it will nominate an ambassador-at-large for the Arctic, raising the profile of American policymaking for the region.

Why it matters: The move comes at a time of increased militarization in the far north, with NATO members squaring off against Russia, and at a time of rapid climate change that is making the Arctic more accessible.

The big picture: U.S. Arctic policy is currently handled by a coordinator within the State Department. The White House is seeking to elevate such a role to a full ambassadorship, pending confirmation from the Senate.

- In recent years, Russia has moved to establish multiple military bases in its Arctic territory, while NATO members have conducted drills and worked to counter the Russian threat.

- With the region’s temperatures increasing three times faster than the rest of the world, melting sea ice is opening the Arctic Ocean up to trade and military patrols.

Context: Until recently, the Arctic was a region characterized by cooperation, rather than competition.

- That dynamic began changing prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the war led Arctic countries to suspend their participation in the Arctic Council.

Coalition Calls for Securing Rights of Indigenous Peoples

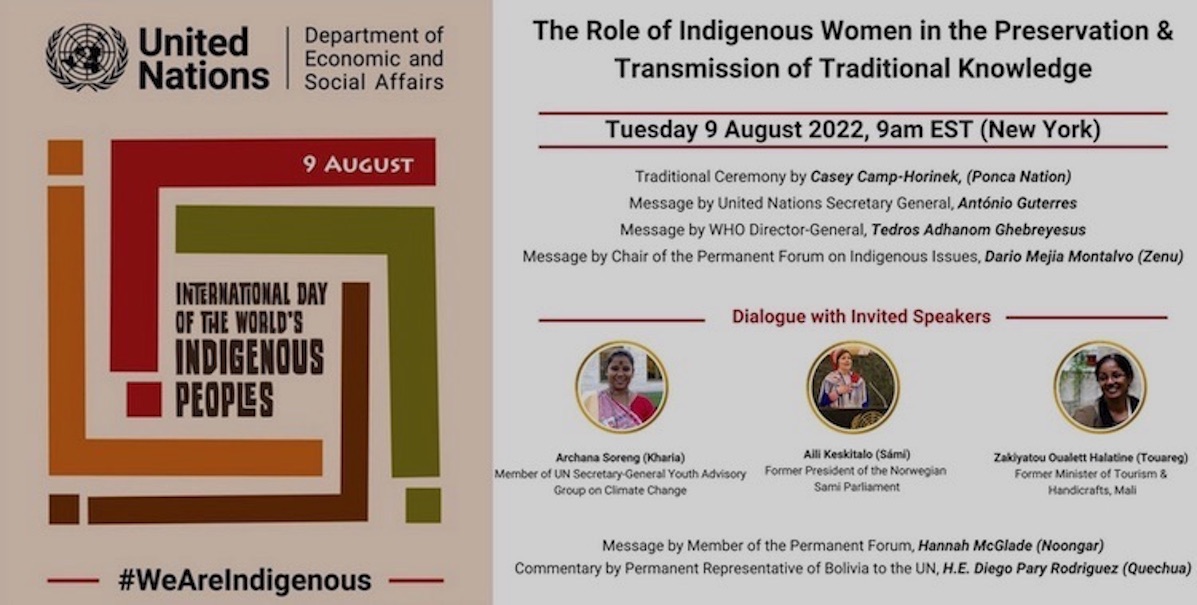

On August 9, 2022, the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous leaders will launch a new site—www.sirgecoalition.org—as part of the official public announcement of a new coalition to Secure Indigenous People’s Rights in a Green Economy (SIRGE Coalition).

The minerals necessary for renewable energy minerals, such as nickel, lithium, cobalt, and copper are critical to the development of a green, low-carbon economy. As demand for these transition minerals is skyrocketing, increased mining threatens Indigenous rights and territories where there is not a comprehensive assessment of risks and harms to Indigenous Peoples, and complete participation of Indigenous Peoples who are impacted.

In order to solve the growing climate emergency, a true Just Transition to a low carbon economy requires governments and companies involved in the new green economy to observe and implement the rights of Indigenous Peoples enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, including the right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent.

Cultural Survival, First Peoples Worldwide, Batani Foundation, Earthworks, and the Society for Threatened Peoples have launched the SIRGE Coalition as a platform to champion a Just Transition to a low-carbon economy. SIRGE Coalition is calling upon government, corporate, and financial decision-makers to avoid the mistakes and harms of past resource development by protecting the rights and self-determination of Indigenous Peoples around the globe, many of whom live on lands rich in transition minerals.

A few of many examples of Indigenous Peoples currently experiencing harms and threats from unconsented development of transition minerals include:

Peehee Mu’huh, or Thacker Pass, sits at the southern edge of the McDermitt Caldera in Humboldt County, Nevada. Lithium Americas is attempting to develop a lithium mine on these lands, which are sacred to Shoshone and Paiute Peoples.

In Guatemala, members of the Indigenous Q’eqchi’ community peacefully blockaded the Fenix Nickel Mine to protest the lack of consultations and Free, Prior, and Informed Consent for the mine, which has polluted their traditional fishing grounds in Lake Izabal.

In Russia, Indigenous communities on the Taimyr Peninsula suffered food insecurity after a fuel spill in 2020 from a subsidiary of Nornickel—a mining firm that supplies some 20 per cent of the world’s Class I nickel needed for electric vehicle batteries—polluted local waterways. Despite pressure from companies in the supply chain, Nornickel has failed to respond to requests from Indigenous communities for adequate compensation and restoration of the fragile Arctic environment.

Indigenous territories contain significant concentrations of untapped heavy metal reserves around the world. In the United States, a study by MSCI estimated that 97 per cent of nickel, 89 per cent of copper, 79 per cent of lithium, and 68 per cent of cobalt reserves and resources are located within 35 miles of Native American reservations. A 2020 study found that mining potentially influences 50 million square kilometres of Earth’s land surface, with 8 per cent coinciding with Protected Areas, 7 per cent with Key Biodiversity Areas, and 16 per cent with Remaining Wilderness.

About the SIRGE Coalition

The SIRGE Coalition’s primary goal is to elevate Indigenous leadership through the creation of a broad coalition and the promotion of constructive dialogue. In accordance with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), the coalition will uphold all rights of Indigenous Peoples, including their cultures, spiritual traditions, histories, and especially their rights to determine their own priorities as to their lands, territories, and resources. Indigenous leadership is essential as Indigenous Peoples conserve about 80 per cent of the planet’s remaining biodiversity.

The SIRGE Coalition is staffed by an Executive Committee made up of representatives from each organization and is governed by an Indigenous Steering Committee made up of two representatives of Indigenous Peoples from each of the seven socio-cultural regions across the globe along with a global chairperson and the chairperson of the Executive Committee, chosen from Indigenous members.

SIRGE Coalition is calling for full implementation of the UNDRIP, including the right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent, in all endeavours related to the extraction, mining, production, consumption, sale and recycling of transition and rare earth minerals around the world.