Historic International Conference on Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Russian Far East Held on Orcas IslandInternational Conference on Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East and the Future of Russia Held on the Island”) reports on a recent international conference focused on the rights and future of Indigenous peoples in Russia’s northern regions.

From April 14 to 17, 2025, a historic international conference took place on Orcas Island, Washington State, USA, on the traditional lands of the Lummi Nation. The event focused on the current situation and future of the Indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Russian Far East in contemporary and post-Putin Russia. It was organized by the Batani International Foundation, the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia, the Indigenous Russia platform, and Russian-Speaking America for Democracy in Russia.

The conference brought together Indigenous representatives from Russia’s northern regions, members of Russian civil society, scholars, politicians, human rights defenders, activists, journalists, and international partners. Together, they engaged in open dialogue on Indigenous rights, Russian imperial policy, decolonization, and the democratic future of Russia. A cornerstone of the event was the adoption of a landmark document titled the Orcas Island Declaration: A Statement of Reconciliation and Respect.

April 15 – Day One

The first day featured four key sessions:

- The Situation of Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East

Representatives of the Itelmen, Sámi, Dolgan, Udege, Shor, and other Indigenous groups shared accounts of the rights violations and challenges faced in their regions. - Contemporary Challenges

This session addressed the effects of repression, rights violations, and environmental exploitation, along with insights from international institutions on legal protection and advocacy. - The Future of Russia: Decolonization and Self-Governance

Experts discussed possible models for a post-imperial Russian state that would respect Indigenous rights and self-determination. - Collaboration with Pro-Democracy Movements

Participants reviewed the current state of cooperation between Indigenous organizations and Russia’s democratic opposition, proposing practical steps to strengthen dialogue and coordination.

April 16 – Day Two

The second day was devoted to the collective development of the conference’s final document. After intensive discussions and consultations, participants adopted the Orcas Island Declaration: A Statement of Reconciliation and Respect.

Adoption of the Orcas Island Declaration

The declaration serves as a foundational document that:

- Condemns colonial policies, forced assimilation, and repression against Indigenous peoples in Russia;

- Emphasizes the need to restore historical justice;

- Commits to collaboration with democratic forces for a future based on equality and human rights;

- Calls for the creation of a permanent dialogue platform;

- Sets concrete goals, including monitoring rights violations, offering legal assistance, developing legislative initiatives for Indigenous rights and land/resource protection, and advancing research and education projects.

Inspired by reconciliation efforts in Canada, the U.S., Australia, and Norway, the declaration urges Russia to undertake a similar path—acknowledging its colonial legacy, restoring respect for Indigenous communities, and enacting institutional reforms. The document is more than a conference outcome; it is a moral and political guidepost for those advocating for the rights of Russia’s Indigenous peoples.

In the afternoon, the Lummi Nation hosted a community event for conference participants and residents. Speakers included representatives of the Native American organization Se’Si’Le, as well as Pavel Sulyandziga, Tyan Zaochnaya, and Vladislav Inozemtsev. This gathering symbolized international solidarity and underscored the shared histories of colonization and the global movement for Indigenous rights.

April 17 – Day Three

On the final day, conference participants visited the Lummi Nation reservation and met with members of the Tribal Council. This visit was both a gesture of respect and gratitude and a first step toward building a lasting partnership between Indigenous peoples of Russia and the United States.

The conference marked a significant milestone toward envisioning a new Russia—democratic, inclusive, and respectful of every nation’s right to self-determination and dignity.

Valentina Sovkina: This reminds me of an unequal marriage

Sovkina V.V., Member of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues

22.02.2025

Lately, I have written little and rarely write about public events in which I participate and my opinions on them. However, I want to talk about this particular event, as it also concerns the Lovozero district.

On February 12, a meeting of the working group (hereinafter referred to as WG) was held, organized by Norilsk Nickel to engage with the Sámi on the development of the Kolmozero lithium mining project. The meeting was held online and was attended by company representatives (now officially no longer Norilsk Nickel, but “Polar Lithium” – a subsidiary of Norilsk Nickel and Rosatom), the Council of Indigenous Representatives, members of the Sámi community, and invited experts – Antonina Gorbunova from KMNUnion and Alexey Tsykarev, an expert on indigenous rights and public diplomacy.

I participated in the WG’s work for the first time on September 7, 2023, at the invitation of Alexey and Antonina. The outcomes of these meetings are well covered on the website. What was unusual this time? The fact that the Council of Indigenous Representatives under the Government of the Murmansk Region participated in the meeting almost in full.

In 2009, during the tenure of Governor Y. A. Yevdokimov, the Council of Indigenous Representatives under the Government of the Murmansk Region was allegedly created at the request of Sámi communities. However, in reality, it was established in opposition to the Council of Authorized Sámi Representatives, also known in governmental circles as the Sámi Parliament, which was elected at the 1st Sámi Congress in December 2008.

The government did not adopt the resolution of the 1st Congress but instead approved its own council solely to seize the initiative from the Sámi representative body and suppress at its roots any emerging self-governance and independence of our people. This is an old and predictable story—across Russia, authorities have created such organizations to control civil society.

Now, back to our meeting… As for the session itself, several issues were discussed:

- Actions to be taken when discovering an archaeological monument: documentation and avoiding impact.

- Conducted archaeological research, the identified cultural heritage site, and recommended follow-up work.

- Promotion and protection of indigenous rights in the context of potential impacts on cultural heritage.

- Information on the Kolmozero lithium deposit development project in the Murmansk region.

- Interaction with indigenous and reindeer herding communities.

- Methodology for calculating damages incurred by associations of indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Russian Far East.

Basically, as always at such meetings, the main speakers were company representatives and participants of the Kolmozero project—those carrying out assignments and research. Maksim Khomyuk asked a few insightful questions. I asked him to send them to me, but he referred to being busy and promised to do so later. I’m waiting.

I don’t want to go into details, but I would like to highlight a few points:

1.

I found out about the meeting by chance, through third parties, and after learning about it, I had to contact my UN colleague Antonina Gorbunova, asking her to send me the participation link. She did, for which I am especially grateful. On the one hand, it was good that I managed to participate; on the other, the level of communication from the company and those organizing this interaction leaves much to be desired. Information about these meetings simply does not exist in the public domain. A regular person cannot find it, and to attend, one must actively push their way in, knocking on doors to be let through. In my opinion, it would be much more convenient if this information were published in open sources so that any Sámi representatives—and others—could participate. Even if they don’t speak, they could at least listen and have the opportunity to ask questions in the chat.

For example, there are groups on VKontakte: “Lovozertsy” (7K members), “Krasnoschelye” (1K), and “Krasnoscheltsy, Unite” (1.7K), consisting of current and former residents of the Lovozero district. I’m sure they would find this information interesting. It would be possible to include those villagers who wish to participate in such meetings.

As for me personally, I am willing to participate and I am interested in learning about the project, but every time I have to push my way in, so to speak, “break through.” It’s strange that when I ask questions or try to take part in regional and public events, I am seen as an opposition figure or someone asking inconvenient questions. But what about dialogue? I am certain that it is impossible to build one with a silent community.

2.

The fact that the members of the Council under the government participated in full is, on the one hand, a good thing—it increases the number of informed individuals. However, on the other hand, I was concerned by a statement from a company representative during the meeting, saying that they had found a platform for discussing FPIC (Free, Prior, and Informed Consent) in the Council.

It is important to remember that this Council is formed by the Murmansk Regional Government, which also approves its composition. In other words, conducting negotiations with the Council essentially means conducting negotiations indirectly with government representatives who control its activities. Of course, this is convenient for both the company and the authorities.

The situation becomes particularly awkward (or unethical?) considering that Elena Almazova is a member of the Council and, in fact, controls its work while holding three different roles:

- a) A member of the Council under the Government,

- b) An employee of the State Budgetary Institution “Center for the Peoples of the North,” which is subordinate to the Ministry of Internal Policy,

- c) The Chair of the Association of Kola Sámi, which receives funding from Norilsk Nickel under an agreement signed with the company in 2021.

It is difficult to determine whether the right to FPIC, which should theoretically belong to the Sámi people rather than individuals dependent on the administration, has been buried somewhere within the interactions between Elena Almazova, the Murmansk Regional Government, and Norilsk Nickel.

3.

I have heard company representatives complain more than once that the Sámi have to be practically dragged by the hair to attend such meetings, that people are unwilling and do not show up, and that at one of the sessions in Krasnoschelye (which requires hiring a helicopter to organize), only five people attended.

On the one hand, villagers are busy people—it can sometimes be difficult to get us to mobilize. On the other hand, these meetings are often scheduled quite spontaneously. People make plans a week or two in advance, and those plans align with natural cycles and the need to ensure their families’ livelihoods, which is important.

I believe that such meetings should be scheduled at least a month in advance, with as many people as possible being informed during that time. If company representatives or working group members cannot do this themselves, then at least publish the information in VKontakte groups—I already mentioned them above. People will sort it out there, and those who are genuinely interested will come.

At the same time, I do not absolve the residents of responsibility for taking an interest in an industrial project. What will happen, and what will remain after it is completed?

Additionally, meetings could be held in a videoconference format. With prior notification, organizations and cooperatives could arrange participation venues. For example, in Krasnoschelye, people could gather at the “Olenovod” office, the community center, or the administration building, where there is a good internet connection. That way, instead of joining individually via mobile phones, they could participate as a group, discuss matters on the spot, and ask questions directly.

4.

But in my view, the main reason there isn’t much interest in this process is that people have consciously taken the position that this project is necessary for the country, that the state and business—especially Rosatom, as a state-owned company—have already made their decision in advance, and that the project will be implemented regardless of whether anyone wants it or not.

To me, this feels like an unequal marriage—where the parents and the groom have already discussed everything and made all the arrangements, so the bride’s opinion no longer matters. The only thing she is left to decide is whether she would rather keep an iron or a frying pan from her dowry.

A company representative stated that they have already determined how much the company should pay the agricultural cooperatives Olenovod and Tundra for giving up their pastures to Polar Lithium. But the work of this so-called working group—and, more broadly, the relationship between the Sámi and the company in this project—is not a partnership between equals who respect each other. Instead, it resembles the dynamic between an all-powerful master and a group of petitioners from among the people, merely begging for their concerns to be acknowledged.

5.

In this regard, the response from the company representative to my question was quite telling. I asked, “What will happen if the company does not receive FPIC—Free, Prior, and Informed Consent—from the Indigenous people?” To which Vasily Sergeyevich replied, “We have all the resources to conduct thorough negotiations and offer the conditions under which the project can be implemented.”

On the one hand, there’s nothing to argue with. But on the other—how is this not the response of a wealthy groom to a bride, leaving her with no real choice?

In conclusion, I am open to an equal dialogue. If lithium is truly indispensable and needed by the country, then we must carefully study the project and make decisions with mutual respect and cooperation, addressing all critical issues—not only for the project participants but for the Lovozero district as a whole.

Sourced from indigenous-russia.com

‘Extermination of Entire Nations’: Scientist Maria Vyushkova Counts Russia’s Indigenous War Dead

On her YouTube channel, Maria Vyushkova describes herself as “a scientist by profession, Buryat by ethnicity” and “anti-war and decolonial activist by the sphere of social engagement.”

In the three years since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Vyushkova, who holds a Ph.D. in chemistry, has emerged as the lead expert on the involvement of Russia’s Indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities in the war.

While Indigenous activists long sounded the alarm about the disproportionate mobilization of minorities for the war, Vyushkova was the first to back these claims up with hard data and shed light on the true scale of ethnic disparities in the confirmed Russian-side casualties.

The Moscow Times spoke with Vyushkova about using scientific knowledge in activism, the myth of “Buryats in Bucha” and the seemingly impossible task of counting Indigenous casualties.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

MT: When did you first apply your scientific knowledge to activist work?

MV: Way before the invasion of Ukraine.

When [Russian President Vladimir] Putin ordered to install cameras at polling stations in 2012, [pro-democracy] activists decided to take advantage of it. They downloaded the videos to count how many people actually voted in the election and check for possible irregularities in the vote-counting process. I was one of the volunteers doing this…and saw a lot of terrible things happen on those recordings.

MT: You joined the Free Buryatia Foundation with the start of the full-scale invasion…

Yes, I was one of its co-founders.

MT: …and there your ability to merge science with activism flourished.

It turned out that no one else in the foundation had any experience working with data…So I was reviewing obituaries [of soldiers], keeping the count of the deceased, trying to understand why so many of them were from Buryatia, and so on.

Rumors that it was the Buryats who had killed civilians in the Ukrainian town of Bucha during its occupation by Russia played an important role in shaping my work.

I was educated at a highly respected scientific school and taught that a true scientist must question everything. So I started investigating these rumors because nobody else questioned them and I wanted to understand what was behind them, how it all actually happened.

I looked at the lists of the deceased soldiers compiled by Mediazona volunteers to see which ones died in the town of Bucha in March 2022. It turned out that it was mostly paratroopers from Pskov [a Russian region neighboring Estonia, Latvia and Belarus] who had been dying there throughout the entire month, which didn’t quite align with the picture presented by the media. So I thought: ‘Okay, something doesn’t add up here.’

As I continued gathering evidence, comparing sources and cross-referencing prisoner testimonies, I realized that these were, indeed, the paratroopers of the 76th Pskov Airborne Division — a conclusion also reached by the Conflict Intelligence Team and supported by the surveillance footage and other materials published by Ukraine.

MT: But the myth about ‘Buryats in Bucha’ lives on, doesn’t it?

Yes, it spread widely and became very popular — not just in Russia, but also in Ukraine and the West. Do you remember the Pope’s controversial statement?

Whenever media outlets mention Russian war crimes, there is an excessive focus on representatives of Asian ethnic groups. No one wants to deal with this uncomfortable topic — people are afraid that accusing Ukrainians [of racism] might be perceived as morally inappropriate. But this issue needs to be addressed.

Some evidence from prisoners signals that ethnic Buryat POWs in Ukraine are treated worse than Russian ones. This is a troubling trend. It means we can no longer encourage Buryat soldiers to surrender because no one knows what could happen to them.

I’m also afraid that Russian propaganda could abuse this trend to encourage people in Buryatia — and other Asian republics — to join the war to seek revenge for their relatives.

MT: Could you describe the process of gathering information on the ethnic composition of casualties on the Russian side in the war in Ukraine?

In the Free Buryatia Foundation, we focused on three geographical areas where Buryats live: the republic of Buryatia, the Irkutsk region and the Aginsky district of the Zabaykalsky region.

We collected obituaries from social media, posts made by relatives, information sent to us in private messages and reports on local television.

MT: Many Indigenous people adopted Russian first and last names as a result of Moscow’s forced russification and Christianization policies over the centuries. So how exactly do you decipher someone’s ethnicity?

I and my fellow volunteers don’t just look at the name and the photo. We examine what is written in the obituary, where the person was from, what language the comments are in, whether those comments are from relatives, and so on.

Ethnicity is a very complex matter and deciphering it is not simple. It is impossible to automate that process.

In a study published in the Journal of Computational Social Science, Alexey Bessudnov from the University of Exeter used AI to search for ‘ethnic’ names in the lists compiled by Mediazona. But frankly, I disagree with his conclusions.

MT: You have recently switched your focus on counting losses among the small-numbered Indigenous communities of Siberia and the North. What prompted you to do that?

No one talks about them, but when you rank ethnic groups by the number of deaths per capita, Chukchis, Udeges, Eskimos and Nenets are far ahead of both the Buryats and Tyvans, for example. Small-numbered Indigenous communities are overrepresented in all lists, including those of soldiers recruited from prisons — most likely, excessive incarceration among these peoples also plays a role.

For instance, for the Nenets [whose total population in Russia is around 50,000] per capita losses are roughly the same as those of the Tyvans [who number at 295,000].

Another example: the village of Elabuga in the Khabarovsk region. Eighty Indigenous families are living there and 15 men from those families were mobilized, while another 10 supposedly signed contracts as ‘volunteers.’ These are horrifying numbers.

These communities need men to sustain their traditional way of life, which means they may lose their cultural identity altogether as a result of this war. This is essentially the extermination of entire nations — it’s terrifying.

MT: You also monitor general trends in Russia’s war losses; could you tell us what the latest figures reveal about the situation on the front line?

I won’t be the first to say this, but 2024 was the bloodiest year of this war. The rate at which deaths are increasing has grown dramatically.

The second notable trend is the shift in losses toward the west [of Russia]. That is, Buryatia is no longer among the leading regions by casualty numbers. Instead, the top are…Bashkortostan and Tatarstan, as well as the Sverdlovsk and Chelyabinsk regions.

The situation with Bashkortostan and Tatarstan is catastrophic. The number of casualties from there continues to rise with no end in sight. The two republics are large regions population-wise — especially compared to Buryatia — but they still rank around 20th in deaths per capita out of 83 regions plus several occupied territories. This means their per-capita losses are already significantly above the national average. They have even surpassed the republics of Sakha (Yakutia) and Kalmykia.

This surge in losses began after mobilization… When the assault on Avdiivka started in October 2023, I noticed a sharp increase in casualties from Bashkortostan. At the time, I predicted that Bashkortostan would take the lead in losses — and that prediction came true.

Moscow region is also now in fourth place by losses — something we haven’t seen before. Although there are many military units in the region, they haven’t been heavily involved in active combat until a certain point in the war. It seems [the authorities] deliberately tried to avoid losses [among soldiers] from Moscow and regions around it, but now they are also being sent to the grinder.

MT: What do you feel when processing all these lists and statistical data?

It’s really hard to look at all of this. I feel like I got to know at least 500 dead men in person while manually processing all the information.

It’s terrifying.

Especially when it comes to small-numbered Indigenous communities who are 100% victims of this situation because they are heavily dependent on the government and often have no access to qualified legal assistance.

None of them have ever tried to challenge [the receipt of military] mobilization [summons] in court — even though there are grounds for it — simply because they can’t get access to a competent lawyer who is also brave enough to take on such a case. That’s the first issue.

The second issue is their catastrophic dependence on the state because their traditional way of life has essentially been criminalized. Russian environmental protection laws not only fail to protect nature but they are also shaped to turn these people into criminals.

It’s terrifying to witness the death of men from these communities because you realize that in one or two generations, entire cultures could easily disappear — and no one knows or cares about that.

Sourced from indigenous-russia.com

Ironic notes on legitimacy, among other things…

Hearings on enhancing participation of indigenous peoples at the UN Human Rights Council

have concluded recently in Geneva. These hearings are part of the process of implementing

decisions of the UN World Conference on Indigenous Peoples held in 2014.

For reference, the World Conference is a special form of the UN General Assembly meeting

attended by the state and government leaders.

Many important things happen around this process. There are many interesting things to

communicate from participating and observing what is happening. I want to share my

impressions on the participation of “official” Russians, i.e. government representatives and their

puppet indigenous representatives.

I would like to perambulate my observations with a story that preceded the UN World

Conference on Indigenous Peoples in 2014. In order to prevent independent leaders and activists

of Russia’s Indigenous peoples from attending the UN General Assembly, the Russian

government (and most likely the FSB, since the Russian Foreign Ministry was unaware of this

action), carried out following special operations in the backstreet gang style:

1) 2) The border service officers at Sheremetyevo cut out pages from the passports of the

World Conference delegates Rodion Sulyandziga and Anna Naikanchina not letting them

out of the country;

Unknown people punctured tyres of the car, in which delegates Valentina Sovkina and

Aleksandra Artieva traveled from Murmansk to the Norwegian border and, when that

didn’t help, tried to take away their passports by twisting their arms. All of this happened

in front of the police officers who were just standing by and watching the violence

unfold.

3) On the day when delegate Zinaida Strogalschikova had to travel to the Conference,

“unknown people” poured some substance into her door lock in Petrozavodsk, so that the

door had to be forced open. Naturally, there was no longer any talk of any flight.

4) FSB officers removed the Crimean Tatar delegate from a train, taking all his documents…

When the Conference delegates learned of these acts, everyone – both governments and

indigenous peoples – condemned the actions of the Russian government except, naturally, the

Russian government itself and its puppet indigenous representatives. The actions of the

government are coherent since one can’t put the blame with himself. But the “puppets” claimed

that the situation was not so straightforward…This is how the “official” Russians (and now they prefer to be named “legitimate” in a

fashionable democratic manner) paved their way to enhancing participation of indigenous

peoples in the UN system.

Russia, China and a few other countries are trying to suspend this process. And, of course, this is

where Russia uses its methods of artful manipulation and propaganda.

Last year the Russian authorities delegated their ‘official” indigenous representatives to attend

the hearings. Ms. Kutsenko (née Shermatova) known in certain circles and running an NGO

named “Luoravetlan” spoke on behalf of indigenous peoples of Russia at the meeting in Geneva

and said that the indigenous peoples of Russia aren’t yet ready to attend and make decisions at a

level that high and reasoned not to rush to the General Assembly meetings as the indigenous

peoples still need to learn. And, naturally, right after this “confession in weakness and inability”

the representative of the Russian authorities spoke against enhancing participation of indigenous

peoples at the UN by arguing – you see, indigenous people themselves admit they are not yet

ready so let’s educate them…

This trick did not work. The process moved forward anyway, and Russia decided to change

tactics. Now the Russian authorities do not seem to object to indigenous peoples taking part in

the General Assembly and the Human Rights Council sessions, but they have started to promote

the idea of official (legitimate) representatives of indigenous peoples taking part in the sessions.

2.

So, about officialism, or legitimacy. Since I can’t bring myself to call these “comrades-

gentlemen” legitimate, I will call them “official”, as they periodically call themselves. And I will

show why they cannot be considered legitimate.

All international events are attended by representatives mostly by three “official” organizations,

i.e. the already mentioned Luoravetlan, as well as the Association of Indigenous Peoples of the

North, Siberia and the Far East of the Russian Federation (abbreviation – RAIPON) and the

organization KMNSOYUZ.

I will tell you a bit about these organizations.

2.1. Luoravetlan was created by an American citizen as an educational center for the indigenous

peoples of the North and played a very important role in the development of legal literacy and

youth leadership. When the center founder left Russia and handed the center over to Ms.

Kutsenko, the organization turned into a sort of an agency for international travels to conferences

and seminars. And when the international travelling became complicated, it turned into one of

the largest recipients of Putin’s presidential grants, taking on the functions of disseminating

Russian propaganda on international platforms. This organization does practically no work inside

Russia. And it has never been an organization representing indigenous peoples.One story about its work with Putin’s grants can be found here – https://indigenous-

russia.com/archives/7803

Another story tells about its work as a “tourism and excursion” agency.

As such, Luoravetlan delegated its people with an “unclear background” to complete different

international indigenous internships. During one such internship, the famous Shor leader

Vladislav Tannagashev met a representative of Luoravetlan, who said at a meeting of interns that

she was a Shor. Naturally, Vlad decided to find out more about her and began to inquire what

Shor clan she was from. At first, this “representative” began to get confused in her “testimony”,

and then, realizing that she had been “exposed”, she said that Vlad was violating her human

rights and was having a negative impact on her. Although he only wanted to find out what

mountain clan she belonged to. It can be added that another representative of Luoravetlan for a

long time introduced herself as an Evenki, until she met real Evenkis. Now these and other

representatives of Luoravetlan have “disappeared” into the vastness of Canada, US and other

enemy territories, which their former boss loved to shame. In simple terms, this organization

simply launders grants allocated for the problems of indigenous peoples through the Russian

government officers who support them.

2.2. RAIPON. This largest organization of small-numbered indigenous peoples of the North,

Siberia and the Far East, created by these peoples back in 1990 during the Soviet Union, has in

recent years become a tool for persecuting independent leaders and activists, a mouthpiece for

official Russian propaganda on international platforms and a conduit for big business exploiting

the lands of indigenous peoples. You can read about some of the actions of this organization and

its leaders here –

instrumentom-obogascheniya-i-lobbizma

korennyh-narodov/33061304.html

akmnssidv-rfraipon-08-04

At one time, this organization actually held elections for its governing bodies, and

representatives of indigenous peoples could influence the activities of this organization, couldparticipate in determining its policies and strategies. And its representatives could call

themselves legitimate representatives of their peoples.

Let me recount to you only a few episodes of what this organization is now, what it has become.

2.2.1. Sakhalin. In 2017, a congress of indigenous peoples of Sakhalin was supposed to take

place and an election of an authorized representative of indigenous peoples was to happen. The

authorities, realizing that their candidates would lose, that the people would support a candidate

they did not like, simply canceled the congress…

2.2.2. Magadan Oblast. Indigenous peoples hold their own reporting and election conference and

elect delegates to the All-Russian congress, while completely ignoring the “instruction” of the

authorities to “select” “appointed” delegates. The next day, the authorities declare the conference

illegitimate, hold a new one and “elect” those who are needed…

2.2.3. Tomsk Oblast. The authorities hold a conference of indigenous peoples in the building of

the regional administration, which is inaccessible without a pass. Those delegates whom the

authorities considered undesirable were simply not allowed into the meeting…

2.2.4. Sakha Republic (Yakutia) and Khabarovsk Krai. On the “recommendation” of ‘invisible

little men’, people who have been declared unreliable are not included in the governing bodies of

the regional associations.

2.2.5. Primorsky Krai. The Primorsky Krai Association is excluded from RAIPON because it is

headed by an unreliable person, and instead of it, another organization is included, which has

fewer people than I have fingers on my hands. But on the other hand, those people there are

obedient.

2.2.6. Murmansk Oblast. Independent candidate Valentina Sovkina wins the elections for the

head of the Kola Sami Association (RAIPON’s regional division). All other candidates

congratulate Valentina on her victory. The next day, the Ministry of Justice recognized the

elections as “invalid”, and RAIPON leaders, who had congratulated Sovkina on her victory just

the day before, began talking about the illegitimacy of her victory.

2.2.7. Taimyr. In the elections for the presidency of the Association of Indigenous Peoples, the

candidate from the government and Norilsk Nickel, Grigory Dyukarev, loses to an independent

candidate. Dyukarev refuses to recognize the election results and calls a new election conference,

where he again loses miserably. But he again refuses to recognize the results of the vote and to

hand over the organization’s documents to the new leader. The elected leader sues Dyukarev.

The government and Norilsk Nickel, realizing that Dyukarev has no authority at all among his

fellow tribesmen, decide to accept the election results and give Dyukarev the order to hand over

the documents to the new leader, transferring him to another “responsible” job.

The new management, having received the documents, discovers that before leaving, Dyukarev

transferred all the money from the Association’s account to Norilsk Nickel’s accounts.2.2.8. In 2013, before the congress of indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East,

the leaders of regional organizations from the Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug, Aleksandr

Novyukhov, and the Krasnoyarsk Krai, Valery Vengo, announced they’d run for presidency of

RAIPON and began their election campaigns. The time for the congress came, and neither of

these leaders did not even mention their nominations. And all because they received an order to

support Grigory Ledkov, a candidate backed by the Putin administration. Novyukhov had to

dump all of his printed campaign materials (beautifully designed, by the way) brought to the

congress to the trash.

Regional conferences of indigenous peoples nominated these people as candidates, but for them,

decisions of their organizations were not as important as commands of their masters, i.e. the

Russian authorities that they serve.

It is absolutely clear that such people will not serve any of their own peoples. They serve their

masters – those who give them real power and privileges – the Russian government and Russian

business.

2.2.9. In 2013, at the same congress, Anna Otke, on the contrary, had no plans to run for

leadership in RAIPON, but she did because she was ordered to, because it was necessary to take

away votes from Sulyandziga. Behind the scenes of the congress, a story was even heard that

Otke cried – she did not want to be involved in this dirty business, but she obeyed. After this

“successful operation” of cutting down votes for Sulyandziga, she was given a seat at the

Federation Council.

2.2.10. Here is a story about the “Congress of the Silent”. This congress of reindeer herders is

called silent because the reindeer herders thus exercised a boycott of government officials. This

happened because the officials ignored the opinion and position of the reindeer herders, making

all the decisions at this congress themselves: –

2.2.11. And also read the story of Mark Zdor, a student, a caring young man who sincerely tried

to help his people by participating in the activities of RAIPON. But, as he tried to defend his

independent position, the RAIPON leadership began to threaten him with arrest and criminal

cases: – https://Indigenous-russia.com/archives/32073

2.3. KMNSOYUZ.

This organization can rightfully be called a subsidiary of Norilsk Nickel.

Created with the full financial and other support of Norilsk Nickel, this organization is trying to

play the role of an expert organization, without getting involved in scandals, in which the other

two organizations periodically plunge into.

This organization, in its work to protect the interests of Norilsk Nickel and the Russian

authorities, invites various experts, including international ones, to cooperate.Carefully hiding its ties with Norilsk Nickel, its real owner, the KMNSOYUZ presents itself as

an organization representing the interests of indigenous peoples. At the same time, it brazenly

deceives both indigenous peoples and the international community, telling tales about Norilsk

Nickel’s advanced experience in observing the rights of Indigenous peoples, hiding what is really

happening in Taimyr and the Murmansk region.

One of the most important jobs assigned to this organization by its owners is the work to lift

sanctions against the Russian government and Russian business. Representatives of this

organization “cry” in all their statements about the suffering caused by Western sanctions. I even

compared the speech of one such “howler” with the speech of a government representative. It

feels like they were all writing this in the same office.

In addition to disseminating propaganda on international platforms, the KMNSOYUZ is actively

engaged in doing this among the indigenous peoples of Russia. The website of this organization

actively posts propaganda stories and materials. Moreover, this is done at a highly professional

level. According to information shared by the leaders of this organization, the KMNSOYUZ

website is run by Gazeta.ru, one of the Kremlin propaganda teams

This is what these “legitimate” official organizations look like.

3.

And now, returning to the meeting in Geneva, where representatives of RAIPON (Mr. Metelitsa)

and the KMNSOYUZ (Mr. Nemechkin) spoke.

By the way, slightly digressing from the main topic, this Metelitsa constantly ends his speeches

with calls to lift sanctions against Russian businesses and officials, which echo with pain in his

heart. And it even delivered a joke: “As always, the meetings and discussions at the UN were

unpredictable, and only Metelitsa was stable. As always, he was talking nonsense.”

So, returning to the loud speeches of Metelitsa and Nemechkin on issues of legitimacy. They

again declared their legitimacy and the illegitimacy of my colleague and friend Yana

Tannagasheva, who represented the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia at

this meeting.

Firstly, I have already described above WHAT the organizations on whose behalf these people

speak are.

Secondly, unlike them, neither Yana nor our Committee (- https://icipr.international) have ever

stated that we represent the indigenous peoples of Russia and speak on their behalf. Our

Committee was created after the start of the war unleashed by Russia against Ukraine, which was

supported by the organizations of these Metelitsa and Nemechkin. My friends and comrades and

I felt it was our duty to state that not all indigenous peoples support this regime and this

aggressive war. We also decided to do everything in our power to tell the truth about this

criminal regime and the violations that this regime commits against indigenous peoples.

Thus, we are in the same position with these people in terms of legitimacy.But there is a huge gap between us and them, two fundamental differences that allow us to be on

the same side of the barricades with other indigenous peoples:

1. We fight for the rights of our peoples (and they defend the Russian government),

2. We tell the truth (and they engage in propaganda and lies).

And thirdly. About the legitimacy of Nemechkin and another such figure, Tsykarev -–

(https://www.thebarentsobserver.com/democracy-and-media/human-rights-expert-from-russia-

considered-a-threat-to-security-and-health-in-finland/129971 ?) –

Why did these two figures, who do not belong to the indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia

and the Far East, suddenly become their legitimate representatives?

Why don’t they deal with the problems of their own peoples? Why don’t they become legitimate

on behalf of their own peoples?

They are educated people, they know international affairs well. They know that if they, as pigs

among race horses, tried to represent American Indians, or Inuits, or Sami, or Maori, they would

have received such a slap in the face that they would not dare to get in a shooting distance of

these issues. And in today’s Russia, everything is possible. It is not the people who decide who

will represent them, but the Russian authorities. And it is very important that the indigenous

peoples of other countries, the international community, understand this when they listen to the

next future speeches about the legitimacy of such “official” representatives.

The European Parliament Discussed the Issues of Indigenous Peoples

On February 4, 2025, the European Parliament in Brussels hosted a discussion titled “Land Exploitation, Oppression of Peoples: Discrimination and Persecution of Indigenous Peoples of Siberia, the North, and the Far East.” This event was organized by the Anti-Discrimination Center “Memorial” (Brussels) in collaboration with Lithuanian MEP Rasa Juknevičienė. It continued the partnership initiated on October 25, 2023, during the event “Resisting Russian Colonial Pressure: Voices of Different Peoples” held in the European Parliament.

Moderated by Rasa Juknevičienė and Stefania Kulaeva from ADC “Memorial,” the discussion featured speakers including Vladislav Tannagashov, a founding member of the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (ICIPR); Mark Zdor, a native of Chukotka, ICIPR member, and anti-war activist; Dirk Schuebel, Head of the Russia Division at the European External Action Service; and Anastasia Crickley, an expert on minority rights and former chair of the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. The event began with a screening of the first part of the documentary “Shor Gold.”

Speakers highlighted their support for Ukraine and condemned Russian aggression. They detailed how Russian authorities are destroying the habitats of indigenous peoples, repressing protesters, and decimating male populations in native villages through mobilization, turning residents into “cannon fodder.” Both primary speakers and other participants emphasized the discriminatory nature of Russia’s national policies, including the suppression of the cultures, languages, and religions of minority peoples.

Dirk Schuebel expressed support for Ukraine and activists opposing Russian aggression, affirming readiness to back such initiatives. MEP Rasa Juknevičienė discussed a European Parliament resolution emphasizing historical responsibility and the connection between history and current issues. She shared her personal experience overcoming Russia’s imperial influence on the Baltic states, fighting for Lithuania’s liberation, and thanked Ukraine for its courage in battling for independence and democracy.

An ADC “Memorial” expert discussed protecting indigenous rights as part of anti-discrimination efforts, expressing support for organizations like the ICIPR, which have been labeled as extremists and terrorists in Russia merely for peaceful advocacy. ADC “Memorial” unequivocally condemns such repression of indigenous rights defenders and minority rights advocates, expressing solidarity with their principled human rights and anti-war stance.

The U.N. and Indigenous Peacebuilding: An Untapped Partnership

In December 2024, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a landmark resolution advocating for the inclusion of Indigenous peoples in peace agreement negotiations, transitional justice processes, conflict resolution, mediation, and constructive arrangements. This move underscores the recognition of Indigenous communities’ unique contributions to peacebuilding.

The First Global Summit on Indigenous Peacebuilding, held at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) in April 2024, played a pivotal role in this development. The summit facilitated Indigenous leaders’ engagement with U.N. institutions and member states, leading to several significant outcomes:

• Indigenous leaders addressed the U.N. Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) in April 2024.

• Summit attendees briefed U.N. member states during the General Assembly in September 2024.

• The U.N. Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs appointed an official dedicated to Indigenous mediation.

• The summit’s declaration influenced eight articles on Indigenous peacebuilding in the UNPFII’s outcome document and informed language in the December U.N. resolution.

Additionally, the Global Network of Indigenous Peacebuilders, Mediators, and Negotiators was established during the summit. This network aims to promote Indigenous practices in formal peacebuilding efforts in the coming years.

Given that 80% of the world’s conflicts occur in biodiversity hotspots where Indigenous peoples reside, recognizing and integrating Indigenous knowledge in peacebuilding is imperative. Documenting and understanding the diverse methods Indigenous communities have used for peacebuilding throughout history is essential for effective conflict resolution.

In summary, the U.N.’s recent resolution and the initiatives stemming from the Global Summit on Indigenous Peacebuilding highlight a growing acknowledgment of the vital role Indigenous peoples play in global peace efforts.

Russia’s Supreme Court designated 172 indigenous groups as “terrorist” organizations

On November 22, 2024, Russia’s Supreme Court designated 172 indigenous groups as “terrorist” organizations, alleging their involvement in promoting secession and supporting Ukraine’s military efforts, as announced by the Prosecutor General’s Office.

Authorities assert that these groups function as “structural subdivisions” of the Free Nations of PostRussia Forum, a Poland-based entity established in 2022. This forum identifies itself as a platform advocating for the decolonization and division of Russia into 41 independent states.

The Prosecutor General’s Office stated that the organization is led by self-proclaimed leaders of national-separatist movements who have fled abroad, aiming to fragment Russia into smaller states under the influence of “unfriendly countries.”

Previously, in 2023, the Prosecutor General’s Office labeled the Free Nations of PostRussia Forum as an “undesirable organization,” citing threats to Russia’s constitutional order and security, thereby criminalizing any interaction with the forum.

The Supreme Court was scheduled to review the request to classify the forum as a “terrorist organization” on November 14, 2024.

Among the groups listed in the recent ruling are the Baltic Republican Party, the Ingria movement, and the Free Yakutia Foundation—three organizations already labeled “extremist” by Russia’s Justice Ministry earlier this year.

Sargylana Kondakova, co-founder of the Free Yakutia Foundation, an Indigenous rights group from the republic of Sakha (Yakutia), refuted the authorities’ characterization of her organization. She emphasized that the foundation is not part of the Free Nations of PostRussia Forum and does not identify as a nationalist separatist movement. Instead, the foundation focuses on advocating for the rights of Indigenous people in Sakha and combating propaganda within the republic. Kondakova added that while they consider themselves a decolonial movement, their goal is not the partitioning of the Russian Federation into multiple states.

In June 2024, the Supreme Court banned a vaguely defined “anti-Russian separatist movement” as “extremist,” though rights groups have noted the absence of any formally established organization by that name.

Subsequently, Russia’s Justice Ministry labeled 54 Indigenous groups and the U.S.-based Free Russia Foundation as “extremist” organizations.

These actions have raised concerns among Indigenous rights advocates and international observers regarding the suppression of Indigenous movements and the potential infringement on the rights of minority groups within Russia.

“Listening to comments from Russian opposition experts about yet another live broadcast featuring Putin (I haven’t watched those broadcasts in years), I was reminded of a story from about 10 years ago.”

United Russia was holding a meeting in Khabarovsk. Boris Nemtsov and Alexei Navalny first called it the “party of crooks and thieves.” Putin was in attendance. It was yet another staged gathering of subordinates meeting their “tsar.” This event featured not only crooks and thieves but also various activists: environmentalists, youth representatives, philatelists, motorists, and others. Essentially, it was a curated group of leader-loving citizens. Representatives of Indigenous small-numbered peoples were also invited to this meeting.

Before the meeting with Putin, a person from the presidential administration gathered us together. They began handing out pre-approved questions. We were supposed to ask Putin those questions. I refused to take a scripted question. I said that I wanted to ask about an issue that truly concerned my people. The issue was the establishment of a traditional nature-use territory on the Bikin River. In response, I was told that I couldn’t ask my question. Only those willing to read the pre-approved questions would be given the floor. I left Khabarovsk that very day.

Our elder, who agreed to ask the prepared question, remained to represent our people. The question she was given went like this: “Dear Vladimir Vladimirovich! We know you care deeply about preserving tigers. There are many tigers and poachers in our land. I ask you to toughen the poacher penalties and share your plans for saving the Amur tiger.”

The evening of questions and answers began. When our elder was given the floor, she stood up and said: “Dear Vladimir Vladimirovich! I want to share one of our problems with you. Our life is already hard as it is. Now the authorities in Primorye won’t let us catch red fish. We’ve always caught it, and it is a traditional food for us.”

I was later told that Putin’s eyes widened at the unexpected question. He did not know how to respond. So, he turned to the head of the Federal Fisheries Agency, Andrei Krainy. He made Andrei answer it on the spot.

Afterwards, our elder called me. She told me that she had been summoned to the police for questioning. Governor Darkin had ordered a criminal case to be initiated against her. In the end, nothing came of it. They couldn’t find anything to charge a pensioner with.

And that’s what these live Q&A sessions with Putin are like…

Prologue: How Our Indigenous North Was Fractured

I would like to express my gratitude to those who proposed the idea of producing this series and who discussed and brought this idea to life. And many thanks for the invitation to share my thoughts on the ongoing processes that impinge upon scientists, Indigenous people, and others who have been involved in cooperation in the Arctic for many years.

What happened on February 24, 2022, was a true blow to the global community. The death and destruction that Russia has brought onto Ukraine came as a shock to all normal people. Yet even though so many experts and politicians did not believe that such a scenario was possible, it was clear that war was a “natural” continuation of the existence of the Putin regime. It doesn’t matter with whom it will fight and who it will declare its ‘enemies’ – whether it be Russia’s civil society or Moldova, Kazakhstan, or the Baltic countries. Ukraine’s bad luck was daring to choose its own path …

Of course, this war could not help but reverberate in the so-called ‘international’ Arctic community. It was here where cooperation and friendship with Russia was mostly successful, where all parties recognized the Arctic as a ‘territory of dialogue’, where so many bilateral and multilateral ties developed, and where the Arctic Council emerged and flourished as an institution of collaboration and discussion.

2.

An active participant in many processes in the Arctic, I fully acknowledge these developments. We, the Indigenous people of Russia, achieved many important results from these processes – including equal participation in the Arctic Council and involvement in various international scientific and research projects.. In turn, such developments gave us numerous opportunities to negotiate with the Russian government regarding respect for our legal rights and interests. The Russian government was forced to act to seek solutions to our issues and challenges, being fully aware that the Indigenous people of Russia had a voice at the international level that certainly would be heard and supported.

As Arctic cooperation developed in scientific research — for instance, in the areas of safe navigation and biodiversity — cooperation among Indigenous peoples also thrived. From the very beginning the solidarity of the Arctic’s Indigenous peoples was exceptionally high. I recall how in the mid-1990s a Canadian delegation of Canadian government officials and Inuit representatives visited Russia. Vice-President of the ICC (Canada) Violet Ford led the Inuit delegates. The delegation’s mission was to meet with the Indigenous people of Russia and discuss ideas for cooperation. Kamchatka was one of the regions the Canadian delegation visited. Looking at the planned agenda, the Inuit visitors were surprised to see that their ‘business’ program in Kamchatka was full of various kinds of entertainment – visiting volcanoes, geysers and the famous Paratunka spa resort, attending concerts… Absent were any visits to Indigenous communities and there was but one scheduled meeting with Kamchatka Indigenous people.

Puzzled, the Inuit guests from Canada asked the Indigenous representatives from Kamchatka whether they had agreed with the program. It turned out that Russian authorities in charge of the program had ignored the proposals of the people of Kamchatka. Inuit leader Violet Ford demanded that the program be changed to include the proposals of the local Indigenous people. To that, Canadian government officials demurred, responding that they were only ‘guests,’ with no right to request a change to the program. ’Well,’ retorted Violet Ford (I paraphrase here), ‘in this case the Inuit would return home. We won’t participate in an event that violated the rights of Indigenous people of Russia.’ Discreet negotiations ensued, during which the program was changed to include the proposals of the Indigenous people of Kamchatka.

Once at an Arctic Council meeting in the late 1990s, representatives of RAIPON (Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East) raised the issue of violations of the rights of Indigenous people of Russia. The Russian government officials flatly declined to discuss any such violations. I recall how Leif Halonen from the Sámi Council and

Akkalyuk Lynge from ICC immediately took our side and demanded explanations from the Russian officials on the issues raised by the RAIPON representatives.

I recall yet another remarkable incident toward the end of 2001, when the RAIPON delegation became part of the Russian official delegation at negotiations between Russia and Canada. These negotiations were led by the heads of government of two countries. It was literally on the eve of the meeting when we at RAIPON received a call from the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Canada, asking who from RAIPON would be taking part. We didn’t even know about these upcoming negotiations! To our surprise, we were requested to go to the Canadian Embassy right away to get our visas and to fly to Ottawa the next day. Canadian officials explained that if we were to refuse, a huge political scandal would occur. The Canadian public had already been informed by media that for the first time at interstate negotiations between Canada and Russia, Indigenous peoples would not only be the topic of negotiations but active participants in these negotiations. If representatives of Russia’s Indigenous peoples were not part of the official Russian delegation, Canada’s Indigenous representatives might simply walk out in protest. We participated in the meetings and had many productive discussions and agreements with our Inuit and First Nations counterparts.

I also took advantage of this situation to again draw the attention of the Russian authorities to the problems of Indigenous people and their resolution at such a high level. At a press conference of prime ministers, I publicly asked the Chairman of the Russian Government, Mikhail Kasyanov:

“Dear Mikhail Mikhailovich, you very correctly noted that Russia and Canada have a lot in common and similarities. You also said that Canada has many achievements and much experience in issues regarding the development of Indigenous peoples. So why doesn’t the Russian government adopt this experience and begin to implement it, based on Russian realities and Russia’s international obligations?”

To that Prime Minister Kasyanov responded: “I agree with you. Let’s you and I meet after returning home.”

That meeting took place, and we agreed to create a roadmap for resolving the issues of the Indigenous peoples of the Russian North. Such work indeed started, and was quite productive. Unfortunately, however, the situation did not last long. At the beginning of 2004 the Kasyanov government was dismissed, and he lost his position.

And another great sign of circumpolar solidarity with the Indigenous peoples of Russia was the appeal of the Senior Officials of the Arctic Council to the Russian government, when in 2012 the Russian Ministry of Justice decided to suspend the activities of RAIPON. This, and many other similar instances, helped the Indigenous peoples of Russia to conduct equal negotiations with the Russian government and build partnerships with them.

I recollect these stories to illustrate how Arctic cooperation up to a certain point had been very important and progressive.

Of course, it was Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine on 24 February 2022 that was the turning point in making continued cooperation in the Arctic impossible. Nonetheless, for the Indigenous people of Russia, curtailment of cooperation started much earlier. In 2013, the Russian government and the FSB service seized RAIPON — and then turned it into a weapon against independent Indigenous leaders and activists. Today, representatives of RAIPON openly engage in propaganda at international forums (primarily at the UN and the Arctic Council). They talk about all the blessings and the paradise that the Russian state has built for the Indigenous peoples of the North. They write denunciations against independent Indigenous leaders. And after the start of the war in Ukraine, which has been supported by RAIPON, its leaders became war criminals, since they are members of the Russian parliament with whose consent this war was started.

3.

I am very pleased that the authors of this volume and series are sharing their thoughts, stories and memories of arctic collaboration, as well as their ideas about the future. For my part, I would like to express several points regarding the future of possible Arctic cooperation with Russia.

Firstly, I consider it very important that scholars who are engaged in arctic research that involves Indigenous people raise and discuss the issue of colonization of Siberia and the fate of its Indigenous residents. This is not just a question of restoring historical justice. It is an issue of eradicating the lies on which the Putin regime is based, such as Russia following a special path or the Russian people being “God’s chosen ones”. It is the need to “cure”—at least, confront— the imperialism that is rooted in the population of Russia, and most notably among its ethnically Russian citizens.

Secondly, in communicating with many colleagues (government representatives, scientists, experts, Indigenous leaders), I see how nostalgic they are for past times. They expect and hope that the Putin regime will fall – and then everything will return to normal and be just fine. To me this is a profound delusion. Things won’t be the same as they used to be before! And the sooner the arctic community–political, academic, expert–realizes this, the sooner it will be possible to begin building a new system of relations with Russia, for effective interactions in the future.

The previous system of relations regarded Russia as a friendly country “with some of its own oddities and peculiarities.” We are all witnesses what this illusion led to after 24 February 2022.

What needs to be grasped? That “there is a dangerous enemy on the other side” and its “oddities and peculiarities” are not just whims of the regime, but the sources of its strength and danger to the outside world. Going forward, any policy and system of relations with Russia must be based on acknowledging this fact.

Thirdly, and perhaps paradoxically, based on what I said above, it is necessary to continue collaboration with those citizens of Russia who oppose the Putin regime and who wish to continue cooperation with the ‘West’. These persons may not be picketing or otherwise actively protesting the regime. In the current environment in Russia to do so would be a prison sentence. A key criterion for such persons is their refusal to participate in this bacchanalia of “Z-ing” [i.e., displaying the symbol ‘Z’ in multiple forms – eds.] and of “jingoistic frenzy.”

This is especially important for the Indigenous peoples of Russia and for their future. Supporting such persons and collaborating with them also generates an atmosphere of understanding in Indigenous communities of Siberia, where everyone knows practically everyone else. By doing so even in such inhuman conditions one can remain human.

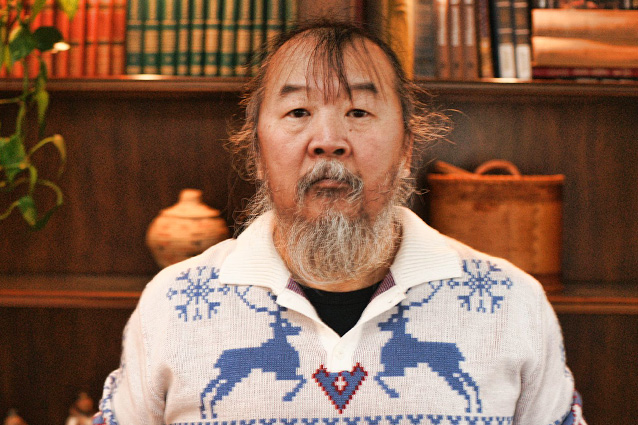

Pavel Sulyandziga, President of the International Indigenous Fund

for development and solidarity “Batani” (Batani Foundation),

Former first vice-president of the RAIPON (1997-2008),

Former member of the United Nations Permanent Forum

on Indigenous Issues (2005-2010), Former member of the United Nations Working Group

on Business and Human Rights (2011-2018)