Russian aggression against Ukraine

and Indigenous peoples of Russia

In the early hours of February 24 th the Russian military build-up along Ukraine’s northern, eastern, and southern borders finally erupted into a full-scale war against Ukraine. Russia’s aggression has already claimed the lives of tens of thousands of people, both among the civilian population, military, and paramilitary groups. It has pulverized Ukrainian cities, destroyed Ukrainian infrastructure, and further resulted in the largest refugee crisis in Europe since World War II. Additionally, it exacerbated the ongoing food crisis in the Global South, increased pressure on Europe’s economy, launched an extended economic recession in Russia, and has driven Russia’s decay into full-blown dictatorship at a pace that would have

been hard to imagine in times of peace.

While the war itself has no declared Indigenous dimension, it will certainly have serious repercussions on Ukraine’s and Russia’s Indigenous peoples and the international Indigenous movement. As Ukraine’s Indigenous peoples traditionally mostly reside on the Crimean peninsula, they have been subject to Russia’s aggression since 2014.

It is difficult to predict how the conflict will evolve and what impact it will have on the survival of the current political regime in Russia. Predictions range from consolidation of Vladimir Putin’s regime, the regime’s transformation into a full autarchy, to a coup by discontented elites or popular uprising eventually leading to a democratic transition and/or territorial disintegration of the Russian Federation.

The present document is not seeking to explore any of these scenarios, but rather looks at some of the already visible effects of Russia’s war in Ukraine for Russia’s Indigenous peoples and beyond. Further, it explores the war’s short and mid-term political and economic consequences for Indigenous communities in Russia. Finally, the report will present recommendations aimed at improving the situation of Indigenous peoples in Russia in these very difficult circumstances and protecting those brave human rights defenders who continue their important work despite spiraling repressions.

Methodology

This report was initiated by the International Committee of Indigenous peoples of Russia (ICIPR) with the support of a coalition of several human rights and Indigenous organizations. To prepare the report, the authors used open sources and interviewed Indigenous rights activists located both in and outside Russia. To protect the identity of informants, some circumstances in the evidence from Russia have been altered. This, however, does not affect the key information, conclusions, and recommendations contained in this report.

Context

Ever since the 1999 appointment of Vladimir Putin as Boris Yeltsin’s successor, the Russian government has been busy silencing the independent and critical voices that flourished in the country in the first decade after the disintegration of the Soviet Union. The first victims of this political course were large media holdings and independent political parties.

After Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012, the Russian government turned its attention to civil society organizations. Draconian laws enacted since 2012 regulate the work of organizations engaged in activities deemed political by the government. The constant harassment of these organizations by the authorities have made it next to impossible to openly and freely discuss issues relating to Indigenous peoples rights, especially where they concern the right to self-determination, and more specifically land rights. A particularly worrisome aspect was the expansion of extractive industries on Indigenous peoples’

territories without their Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), actions broadly supported by Western businesses and governments.

As a result, today, the once vibrant Indigenous activist movement in Russia has been reduced to a handful of people. Those activists must be extremely careful about what they say and do as anyone who openly questions the political and economic choices made by the national and sub-national authorities is at risk of criminal prosecution. A number of prominent Indigenous rights defenders left the country fearing for their own and their loved ones’ safety and freedom. Some of those who chose to stay in Russia are experiencing arbitrary criminal prosecution initiated by the state or extractive companies.

The war in Ukraine has provided the Russian government with a new opportunity to further tighten an already very limited civic space in Russia. Soon after the start of what they insist is a “special military operation,” Russian authorities introduced various restrictions on the rights of freedom of expression and association.

On March 4th , less than one week after the start of the war, Russian authorities approved amendments to Russia’s administrative and criminal codes that effectively criminalize not only the expression of anti-war positions, but even the very use of the word “war” in specific circumstances. Law enforcement practice goes even further. Cases are on record of protesters being arrested for holding up a piece of paper saying “dva slova” (“two words”) that hints at the outlawed two words “nyet voyne” (“no war”) or where protesters were detained just for holding up their hands as if they were holding up a placard.

On March 23rd , Russia’s parliament adopted amendments expanding the ban to include criticizing the armed forces and criticism of all Russian government actions abroad. Additionally, Russian authorities insist that media sources only share information about the war provided or channeled by the Ministry of Defense. Russian authorities consider all other information as misinformation, which, when disseminated publicly, could be punishable by law.

The penalties for committing the offense of “discrediting the Russian armed forces,” including public calls for armed forces to be withdrawn or to stop fighting ranges from hefty fines to long prison sentences. As of today, the number of people who have been detained for their participation in anti-war protests exceeds 16,000 (most of them were released a few hours or few days later, while some were fined according to Russia’s administrative code) and dozens are facing criminal prosecution. Many of them are journalists, civil society activists, or political leaders. There are also examples of the prosecution of Indigenous activists.

Soon after the start of the war, Russian authorities went on a spree of extrajudicial closures and blocking of the last remaining independent media outlets in Russia and Russian- language media based abroad. The last free and notable news outlets were Radio Echo Moskvy, an influential radio station which was closed formally by its own Board on March 1st and the newspaper Novaya Gazeta. The latter’s editor-in-chief Dmitry Muratov was awarded the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize. The newspaper initially tried to adapt to the new rules, but ended up suspending its activities in Russia, succumbing to the ongoing pressure by the government’s media watchdog Roskomnadzor. In April, a group of exiled journalists from the newspaper launched a Latvia-based namesake Novaya Gazeta Europe, Russia’s access to which was quickly blocked by Roskomnadzor. Journalists who chose to stay in Russia attempted to launch a new weekly, called “NO.Novaya Rasskaz-Gazeta,” but this too was blocked by Roskomnadzor.

Further, the last independent TV station operating from within Russia, TV Rain (Telekanal Dozhd) ceased operations on March 4th . In July, TV Rain restarted its operations from Latvia and is currently streaming its programs via YouTube. To date, YouTube remains the only major outlet yet to be blocked. In doing so, the government risks a major outcry from the millions of Russians who use it for entertainment.

It was reported that, between the start of the war and July 2022, the Russian government has blocked over 5,000 internet resources for violations of the newly introduced laws related to the “special military operation.” Therefore, the media that are still operating in Russia do so by almost entirely avoiding the topic of the war in Ukraine or by accepting the rules imposed by the government and are, thus, relying completely on the information provided by the government.

Lastly, authorities are further blocking access to Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. On March 28th , a Moscow court declared Facebook’s and Instagram’s ‘Meta Platforms Inc.’ an extremist organization and banned it in Russia. While authorities emphasized that the use of Facebook and Instagram is not punishable, there are fears that this might change if authorities find it to be a useful tool for silencing its critics. As a precaution, when crossing the Russian border, some Russian Indigenous and political activists have begun erasing all applications from their smartphones that authorities could consider extremist in order for them not to be found in case of an inspection by the FSB or other law enforcement authorities.

Thus, by late March, the Russian government had established a near-complete monopoly on the narrative of the ongoing war in Ukraine. For the most part, it is only politically active and urban citizens that have the means to access independent information about the conflict in Ukraine and its political, economic, and environmental dimensions.

Today, Russian independent journalism exists mostly in the form of citizen journalism (private YouTube channels, Telegram channels, etc.). Some Russian media continues its work from abroad, but, with rare exceptions, is only accessible to Russian users via virtual private networks (VPN). To use VPNs, however, one needs to understand the benefits of its use, to have access to these networks, and the capacity to use it. Also, one needs to be able to pay for it, now complicated for Russian bank card holders as their cards can no longer be used for transactions abroad. They are, therefore, not very widely used, especially in remote areas where many Indigenous peoples live. While the use of VPNs is not criminalized, there are indications that Russian authorities are not happy with their growing popularity.

For some, consumption of disinformation is also partly self-imposed. Evidence from Russians abroad shows that some continue to consume and believe Russian state media propaganda, despite having access to independent media.

Yet, the reality for the overwhelming majority of people living in remote areas like Russia’s Indigenous communities is that they have no access to the internet, let alone the skills to avoid restrictions on information access imposed by the government.

“We use only TV to receive information in our village. Mobile internet is expensive and very slow, so we primarily use it for texting with relatives and friends. To surf on the internet, you have to drive around half an hour from the settlement closer to the seashore. We don’t use VPN or anything. My grandson, who lives in the city, told me I could use it now, but I don’t know how to do it. I am not too familiar with all this computer science, and anyway, he says that the government is blocking VPNs,” comments one Indigenous inhabitant of Kamchatka.

Additionally, a new law that will enter into force by the end of the year, introduces a concept of “foreign influence.” This new law replaces the infamous law “On Foreign Agents.” According to it, organizations and individuals do not necessarily need to receive funds from abroad to be branded “foreign agents.” It is enough to be deemed “under foreign influence.” Foreign influence is described in very vague terms and could even be an interaction with colleagues from abroad or with organizations and individuals who already have foreign agent status. A person or organization under supposed foreign influence is banned from receiving public funds, cannot offer education services or teach, nor can they organize public events

such as demonstrations or conferences. They are also subject to a different system of taxation.

All people, including Indigenous activists, who write public texts of a political or apolitical nature and cooperate with foreign counterparts will thus be at risk of being recognized as such. Given that Russian authorities often apply laws retrospectively, foreign influence could be explained by something done in the past.

Impact of the war on Indigenous peoples in Russia

Indigenous soldiers in the Russian army

The Russian media reported that the overwhelming majority of Russian soldiers fighting in Ukraine are not coming from large urban centers in western Russia, but rather from smaller and poorer localities in Siberia and the Far East and the Volga and Caucasus regions.

The percentage of Indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities among soldiers in the Russian

armed forces who are fighting and dying in the war seems to be disproportionately high.

According to our informants, one Indigenous village in Siberia with a population of around two hundred individuals, had five young Indigenous soldiers fighting in Ukraine. Their entire Indigenous nation numbers fewer than 2,000 people.

In many smaller towns and cities in the Russian Arctic, Siberia, and the Far East, contract military service is sometimes one of the very few paid jobs available and better paid than many other public jobs. Those who fight in Ukraine receive additional bonuses. It was reported that the average monthly salary of a soldier fighting in Ukraine is around 200,000 rubles, whereas in March 2022, the average salary in, for example, Tyumen Oblast where Khanty, Mansi, and Nenets Indigenous peoples live, was around 61,000 rubles. Given that Tyumen Oblast leads Russia’s oil and gas extraction, the average salary in many other

regions, especially in remote Indigenous villages, is much smaller.

Some Indigenous activists from Russia informed the authors of this report that armed forces recruitment does not provide potential recruits with realistic information about what to expect in the army. This issue is also supported by other sources. And given that the Russian government severely limits information about human casualties and the war’s brutality in Ukraine, many people who sign contracts do not understand the dangers they are getting themselves into.

There have been confirmed deaths of Indigenous soldiers from Chukotka, Khabarovsk Krai, Tyva, Buryatia, and other Russian regions. However, the total number of Indigenous soldiers’ deaths is difficult to estimate as many Indigenous peoples in Russia have Russian names, making it impossible to distinguish them from non-Indigenous servicemen in open databases.

Given the high fatality rate in this war, one can tell that Indigenous peoples are paying a disproportionately high price for the war waged by Moscow politicians. While any loss of life is a tragedy, for small-numbered Indigenous peoples it could be a question of their very survival.

While the death rate is notably higher among ethnic minorities, many of those who return home alive will likely suffer from injuries and long-term mental health problems, including post-traumatic stress disorders. At the same time, Russia’s healthcare infrastructure in remote areas where most Indigenous peoples live has very limited capacity to address these issues.

Finally, when the extent of the crimes committed on occupied Ukrainian territory was made public, there was an attempt to racialize the brutality. Russian social media portrayed these crimes as committed by “savages” from remote corners of the empire, thus characterizing Indigenous soldiers as people who are more prone to violence “due to cultural traits.” Such an interpretation of events was trending not only among the Russian, but also the Ukrainian public. While investigations by Ukrainian authorities into these crimes are ongoing, it is too early to say exactly who committed the horrific crimes against Ukrainian civilians. However, even if Indigenous soldiers had committed some of these crimes as members of the Russian armed forces, one needs to be aware of the racist narrative propagated by such stories as well as the fact that, willingly or unwillingly, it distracts from those higher up in the hierarchy that are actually responsible for breaches of international humanitarian law and who allowed war crimes to take place.

Russian Indigenous movement

For many years now, the Indigenous peoples’ movement in Russia has been divided. For much of recent history, the Russian government has historically divided Indigenous peoples into different legal and political categories, each treated differently: “small-numbered Indigenous peoples” with fewer than 50,000 total population, “Indigenous peoples” with more than 50,000 total population, and simply “peoples” (as in the Caucasus and western Russian regions). This “divide and conquer” strategy has been an effective tool in exerting state control over Indigenous peoples. This report focuses largely on the category of “small-

numbered Indigenous peoples.”

The Russian Association of the Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) is a large umbrella organization for Russian “small-numbered Indigenous peoples” and was once a fierce defender of Indigenous rights in Russia. In the past decade, RAIPON’s role has largely been reduced to rubber-stamping government decisions. The organization came under full control of the regime in 2013. At the time, Grigory Ledkov, a member of parliament for the ruling United Russia party, was promoted to the RAIPON leadership role by the Russian government. To this day, Ledkov remains president of the organization and as such claims a

monopoly to represent forty-one Indigenous peoples of Russia North, Siberia, and the Far East at the national level and internationally.

The other “wing” of the Indigenous movement is mostly represented by Aborigen Forum, an informal alliance of independent Indigenous activists, organizations, and experts on Indigenous peoples rights founded in response to the de facto takeover of RAIPON by the government’s United Russia party.

This division in the movement persists to this day and is only further reinforced by the war.

On March 1st , RAIPON released an address to the Russian president expressing its full support for his decision to start the “special military operation” in Ukraine. The document is signed by leaders of 33 regional chapters of RAIPON, many of whom work for government bodies. On March 3 rd , RAIPON was joined by another pro-governmental Indigenous organization: the Association of Finno-Ugric Peoples of the Russian Federation, whose leadership signed an open statement by the leaders of federal Indigenous and cultural autonomies and civil society institutions expressing their support of Russian leadership.

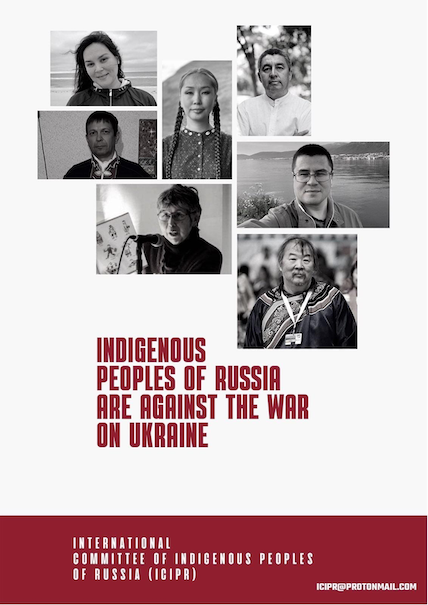

In further response to RAIPON’s statement, seven exiled Indigenous activists from Russia announced their decision on March 10th to establish the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (ICIPR) with an explicit objective of countering the Russian government propaganda relayed by RAIPON.

Given their political persecution and harassment at home, the exiled activists behind ICIPR are unable to visit their home communities. They maintain, however, close contacts with their communities and their peoples and thus give voices to their Indigenous brothers and sisters who chose to or were forced to stay in Russia and who continue their activism less publicly.

Ever since the creation of ICIPR, RAIPON has invested significant resources in trying to discredit the newly established organization and its individual members. They do so by making public statements questioning ICIPR’s legitimacy and accusing them of discrediting the Russian armed forces.

Polarizing attitudes toward the war are also increasingly noticeable among Indigenous peoples throughout Russia. Widespread disinformation and the difficulty of accessing independent information in remote regions, among other barriers, is leading to a split in the Indigenous rights movement. With laws becoming ever more repressive, Indigenous activists are increasingly divided and under growing threat. Authorities pressure communities and activists to comply out of a fear of prosecution.

Finally, Indigenous sources report that their communities are frequently misused for propaganda purposes. This happened, for example, on the Kola Peninsula, where members of an Indigenous community were invited, under false pretenses, to a meeting hosted by local authorities and were then forced to participate in a performance with militaristic symbolism. This is emblematic of the fact that Indigenous people in Russia are not seen as independent agents with rights and needs, but as subjects who do not deserve to be

meaningfully represented, respected, and consulted.

Because critical Indigenous voices fear persecution, they can no longer effectively stand up for their rights and criticize the government, its proxy organizations, and crony businesses. This has a direct impact on their human rights situation in Russia, and the erosion of opportunities to express resistance will likely lead to further intensification of repressions and worsening of Indigenous peoples’ social and economic situations.

International advocacy

The Russian government’s criminal decision to wage a war against its neighbor had a devastating effect on its Indigenous peoples’ participation in international advocacy mechanisms.

Following the start of the war on Ukraine, the Arctic Council, a unique institution in which the Arctic’s nations, Indigenous peoples, and NGOs work on sustainable environmental development and protection of the region, has suspended its work.

Despite different challenges and the fact that, in recent years, Russia’s permanent Indigenous representative – RAIPON – has been mostly relaying the government’s agenda, the Council’s potential in fostering peaceful cooperation in the Arctic has been recognized by most of its members, states, Indigenous peoples, and NGOs alike. Suspension of the Council’s activities effectively put an end to various regional projects, including those involving Indigenous peoples of Russia.

Meanwhile speaking out at the UN has become extremely dangerous for independent Indigenous voices from Russia. Anyone voicing opposition to Russian government decisions at international fora risks intimidation and prosecution in Russia. This is a huge challenge, as participating in international fora is of great importance for the many marginalized Indigenous peoples of Russia. Just how far Russian government representatives may go in their attempt to intimidate independent Indigenous activists was seen at the July 2022 session of the United Nations’ Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP).

On July 4th , the first day of EMRIP’s 15th session in Geneva, indigenous Shor activist Yana Tannagasheva was verbally assaulted and physically intimidated by a representative of the Russian state. In her speech, Tannagasheva drew the audience’s attention to Russian government and business community violations of the rights of Indigenous peoples and spoke about the case of her native village, allegedly burned by a coal company in response to some villagers’ refusal to sell their land to the company. Tannagasheva ended her speech by highlighting the government’s attack on freedom of speech and government harassment and criminalization of Indigenous activists in Russia and called for the UN Human Rights Council to establish a mandate for a Special Rapporteur on the situation of Indigenous peoples in interstate conflicts. During her speech, Sergey Chumarev, a representative of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (deputy department head for Humanitarian Cooperation and Human Rights) sat down immediately behind Tannagasheva. Following her statement, Chumarev insisted on obtaining Tannagasheva’s contact information in an intimidating manner and then insulted the Indigenous activist and violently reclaimed his business card,

presented to her earlier, from her hands. His open hostility was documented by the Geneva Observer, the Swiss Radio Television SRF, and others, and provoked a strong reaction among other participants, who encircled Tannagasheva to form a human shield against the Russian official’s intimidating behavior.

It should be noted that Yana Tannagasheva was forced out of Russia four years earlier and granted political asylum in Sweden. Once again, she was confronted with the fear she and her family constantly experienced when still residing in Russia. The unacceptable and undiplomatic behavior is emblematic of the Russian state’s attitude towards Indigenous peoples of Russia and Ukraine and especially towards women. They continue to persecute those who speak openly about the real situation in the country.

Immediately after the incident, the Indigenous Russia website, possibly the last remaining independent media addressing Indigenous peoples rights issues in Russia, published a statement by the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (ICIPR), of which Tannagasheva is a member, denouncing the behavior of Russian government representatives. Shortly after it was published, Dmitry Berezhkov, director of Indigenous Russia, received an email from the website’s hosting provider, saying it had received a request from the Russian government to remove the page from the Internet within 24 hours. Aware of the fact that this request was politically motivated, the provider declined to act.

However, access to the website from Russia has now been blocked and can now only be accessed via VPN. In his statement at a later EMRIP session, Berezhkov said: “This is the way that Russia immediately responds to the truth about violations of the rights of Indigenous peoples, a truth voiced in this hall. One way or another, we will continue our work to convey information to the international community about violations of the rights of Indigenous peoples in Russia.”

Divided peoples

Indigenous peoples whose ancestral lands are divided by national borders suffer additional impacts of the war when contacts with brethren across the border are severely limited.

The cross-border dimension is particularly evident in the case of the Sámi, who live in both Russia and Nordic countries. Here, the war in Ukraine has resulted in suspension of all cooperation between Russian and non-Russian members of the Sámi Council, the Sámi people’s main representative body. The suspension followed an explicit expression of support by some Sámi leaders in Russia for the Russian government’s decision to launch the war against Ukraine. And although not all Russian Sámi organizations endorsed the government on that issue, the decision to suspend Russian participation was made unanimously by the Executive Board of the Sámi Council, a body that consists of four people, one of which is a representative of Russian Sámi.

While the impact on cooperation between Inuits and Aleuts residing in Russia and those who live in North America and Greenland is yet not as evident as it is in the case of Sámi, Russia’s growing isolation and escalation of its antagonism with the West will likely lead to a reduction in transborder contacts. Some prominent members of the Inuit community in Chukotka publicly supported Russian aggression against Ukraine. Meanwhile, the Inuit Circumpolar Council which, among other roles, represents Chukotka’s Yupiq people has voiced its concern over the suspension of Arctic Council activities in a press release without

denouncing or even mentioning Russia’s assault on Ukraine.

Other Environmental and Social Impacts

One by one since the first hours of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Western governments announced economic sanctions against Russian government agencies and institutions, businesses, politicians, and other individuals. The sanctions severely restricted financial transactions between Russian entities and their foreign counterparts, led to freezing of the government’s financial assets abroad, limited the transfer of technological know-how, complicated Russian exports, and restricted air and maritime transit for Russian aircraft and vessels. It is estimated that the volume of sanctions imposed on Russia is the highest ever imposed on any nation in modern history. Government sanctions were quickly followed by foreign businesses choosing to leave the Russian market on their own initiative, suspending production in Russia, and closing retail outlets there.

In a globalized country like Russia, this led to immediate economic consequences felt by many within Russia, but also beyond its borders. Initially, it provoked panic among the population and spikes in prices for essential goods. Although prices for many goods have stabilized at this point, the sanctions’ long-term effects are difficult to estimate. It is expected that by the end of 2022, the Russian economy may shrink as much as 20%. Meanwhile, Russia is already experiencing shortages of some essential supplies, like medicines. The lack of fuel, food, and medical supplies will hit remote Indigenous communities especially

hard, as many are only accessible by air transport much of the year.

During the highest tensions between Russia and the West since the Cuban missile crisis, and considering Russia’s strategy of silencing any opposition, it seems obvious that the Russian government will prioritize maintaining its military, security services, and law enforcement agencies, both technologically and financially, over providing economic support to vulnerable populations. Indigenous peoples in Russia are among the most vulnerable groups in the Russian population.

Dispossessed of their lands, they are excluded from decision-making when it comes to

resource extraction and other industrial development on their territories. As a result, many

Indigenous communities’ dependence on already meager state welfare for subsistence is increasingly coming under pressure. Today, these groups may face an even greater socio- economic crisis, similar to the one they experienced in the early 1990s. At that time, when the collapse of the Soviet Union led to a breakdown in food supply chains and social services, some communities in the Russian Arctic experienced high levels of food insecurity as a result.

With the closure of Western markets, the Russian government is tightening its focus on markets in India and especially China. While Chinese and Indian businesses are interested in Russian raw materials and the Russian market in general, Western sanctions are a deterrent and they are not prepared to risk their access to much more lucrative Western markets. As a result, they have so far been rather hesitant to respond to the Russian government’s generous invitations to enter its domestic market in order to replace Western

suppliers.

As a consequence of the state of the Russian economy, it seems likely that the government will drop already very limited and ineffective environmental and human rights regulations in favor of shoring up extractive industries to increase the competitiveness of their products in Asian markets. In fact, there are indicators that this has already started to take place. In mid-April, opposition politician Yulia Galyamina wrote that officials in Yakutia have authorized logging in one of Siberia’s last virgin forests for export to China. The forest in question is located on the traditional lands of the Evenki people for whom the forest is the essence of their traditional lifestyle and spiritual culture. Additionally, the environmental impacts of

logging in this area will almost certainly have severe impacts on Indigenous peoples living downstream as well.

Russian mining giant Nornickel may also be using this strategy. So far, the company has relied heavily on the European market to sell products that are in great demand for the green economy transition. With the sanctions imposed on Russia and increasing supply chain instability, the company is considering turning its back on Europe and developing a new focus on Asian markets.

While dependency on exports to Europe was one of the last leverage points human rights and environmental activists had at their disposal to improve the situation of Indigenous peoples in Russia, the sanctions regime increasingly complicates the situation. It is no secret that, e.g., Chinese firms and investors care less or not at all about international environmental and human rights standards. Evidently, a shift in focus towards the Chinese market would most probably lead to even more limited human rights and environmental accountability for Russian extractive companies and their new partners.

Conclusions

As we demonstrated in this report, the Russian authorities’ criminal decision to invade neighboring Ukraine has had devastating impacts on Indigenous peoples in Russia, impacts that have clear demographic, political, and economic dimensions. The war further divides the Russian Indigenous movement in many ways and hinders international contacts and cooperation.

We see that military recruitment in Indigenous communities to fight in Ukraine has been disproportionately high as is the number of casualties among Indigenous peoples. These trends will further reduce already small populations of Indigenous peoples and could possibly result in additional pressure on the already insufficient healthcare and social services infrastructure that remote Indigenous communities can access.

Even before the war, Indigenous peoples living in remote communities have been hit hard by spiraling inflation and suffer from food insecurity and a lack of social services. All these problems are likely to be amplified by the war in Ukraine. Meanwhile in the economic sphere, Western businesses have been steadily replaced with Chinese and Indian companies. This means that Western human rights and environmental accountability standards and mechanisms, however insufficient and imperfect, will be abandoned in order to ensure the quick and easy resupply of the Russian government’s coffers, funds that will ultimately be

spent to fund the war in Ukraine.

Politically, the war has divided the Indigenous movement within Russia, destroyed platforms of effective cooperation between Russian Indigenous organizations and their counterparts abroad, and has seriously impacted transborder cooperation for divided peoples, such as the Sámi, who live both in Nordic countries and Russia. It is quite evident that the Russian government has been active in using proxy Indigenous organizations to amplify state propaganda and to discredit independent Indigenous voices from Russia.

Call to action

The International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia, created by a group of Indigenous activists from Russia in response to the Russian government’s aggressive war on Ukraine, unambiguously denounces the Russian President’s criminal decision to invade Ukraine and calls for the occupation to stop. The Committee also calls on the Russian government to immediately start working with the Ukrainian government on the peaceful return of territories annexed in 2014.

The Committee calls on the Russian government to abandon its imperialist ambitions, to seek peace and reconciliation with Russia’s neighbors, and, instead of spending billions of rubles in destroying lives of thousands of Ukrainian and Russian citizens to invest them in the wellbeing of the most marginalized groups within the country, including the Indigenous peoples of Russia.

Recommendations to the international community

- Support independent Indigenous activists and human rights defenders from Russia

- The holistic security and, especially, the digital security of Russian Indigenous activists needs to be improved. It is increasingly pressing for critical voices to be able to resist state-organized surveillance and repression and protect their privacy.

- The important work of Indigenous and human rights activists at risk of criminalization and repression is dependent on rapid response mechanisms, including urgent relocation from Russia, in case of imminent threats to their physical integrity, life, or liberty.

- Due to numerous financial constraints, including the criminalization of receiving foreign funds, flexible and creative means are needed for providing financial support for independent Indigenous organizations continuing to operate in Russia.

- As activism in Russia becomes increasingly dangerous, it is more important than ever to support capacity and community building events outside Russia for Indigenous activists from Russia.

2. Support initiatives countering Russian government propaganda

- The Russian information space is rapidly shrinking, making it difficult to identify and counter propaganda. Financial and logistical support for mechanisms ensuring the flow of information from independent sources in and out of Russia is needed. Fostering independent Russian media located

both in and outside of Russia are key. - Indigenous students from Russia benefit from education abroad. Study abroad provides an opportunity to gain a realistic understanding of what is going on outside of Russia (as opposed to what Russian government propaganda wants them to believe) and to take a critical look at the political and human rights situation in Russia. This will also allow them to build a network of international contacts and cooperation and thus contribute to better understanding among Indigenous peoples. Ultimately, they will be able to transfer their knowledge to their communities.

- Isolating Russian citizens by blocking foreign travel and limiting their ability to receive visas has several shortcomings. Such isolation a) plays into the Russian nationalistic narrative that the West’s human rights record is no better than that of Russia since Russian citizens are punished summarily; b) threatens one of the few remaining leverage points left to the West; c) further reduces access to independent information, including about the war in Ukraine; and d) closes one of the few protection channels for Russian Indigenous activists and human rights defenders. Russian citizen access to

Western countries must be maintained.

3. Document the human rights situation for Russia’s Indigenous peoples

- Hearings need to be organized in European and other parliaments to provide a platform for repressed Indigenous voices outside of Russia and an alternative to Russia’s state-controlled discourse.

- An in-depth UN report on the influence of the war on Indigenous peoples’ situation in Russia and Ukraine should be commissioned.

- An impartial and independent United Nations mechanism such as a United Nations “Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Russia” is needed. The mandate holder could closely monitor, analyze, and report past and ongoing human rights violations in Russia, including Indigenous rights. The status of a Special Rapporteur would provide its mandate-holder with a certain international legitimacy and standing that is much needed in these polarized times.

- It is further important that international media continue covering issues concerning Indigenous peoples in Russia in order to portray balanced coverage of the challenges facing them.

- Facilitate meaningful and independent participation of Indigenous peoples from

Russia at international events and platforms:

- Indigenous leaders from Russia must be able to speak freely about their concerns and protect their rights both domestically and internationally. Specifically, they require targeted support and protection when speaking at international fora and UN meetings. Representatives of the Russian

government and any other individuals that have a history of attacking, threatening, and/or intimidating independent Indigenous activists and human rights defenders participating in international events should be banned from attending such meetings in the future. - Since official representatives of the Russian state and representatives of organizations affiliated with the state are direct accomplices of Russian aggression against Ukraine, they can no longer be considered independent and neutral actors. Their access to UN mandates should be restricted as

firmly as possible. - As RAIPON is not an independent non-governmental organization but, in reality, an instrument of the Russian government that is misused to manifest demonstrably false unity and to conceal the problems facing Indigenous people in Russia, RAIPON members shall not be allowed to occupy roles

reserved for civil society (for example, as a Permanent Participant of the Arctic Council, when that entity resumes operation).

5. Practice business responsibly with Russia

- While we share the belief that economic sanctions are an important means of pressuring the Russian government to stop its aggressive war on Ukraine, we believe it is important to reflect on sanctions that could be implemented without harming the most vulnerable populations in Russia, including

Indigenous peoples. - It is important to document attempts by Russian companies to bypass economic sanctions or access Western markets without following best practices in human rights and environmental accountability (including the principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent on the lands of Indigenouscommunities where resource extraction, infrastructure, industrial, and other development occurs).

- Due diligence standards must apply throughout the supply chain, not only to its last segments. Complete enforcement of these standards will ensure that Russian businesses are not using third-country intermediaries to access Western markets without following best practices.

- Growing demand for minerals needed for the transition to a greener economy is leading to increasing industrial pressure on Indigenous territories, including in Russia. While the transition to a greener economy is welcomed, it is important that it not occur at the expense of human rights of Indigenous

peoples’ rights.

For comments please contact the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia

at: [email protected].