RECONCILIATION AGREEMENT BETWEEN GERMANY AND NAMIBIA:

A PATH TOWARDS REPARATION OF THE FIRST GENOCIDE OF THE 20TH CENTURY

The wounds inflicted by the great massacre of 60,000 Herero and 10,000 Namas in the former colony of Southwest Africa have yet to heal. Added to the concentration camps and slave labor, are the scars from the exhibition of human remains in museums and the manipulation for racist scientific theories. After a century of denial, the governments of both countries agreed to compensation of 1.1 billion euros over a period of 30 years. However, the descendants of the victims do not feel that their demands are heard.

On 28th May 2021 Germany issued an announcement that it had reached a Reconciliation Agreement with Namibia. This agreement acknowledged that it committed genocide against the Herero and Nama peoples in South West Africa (now Namibia) between 1904 and 1908. The agreement has yet to be confirmed by the German Bundestag (the German Federal Parliament) and the Namibian Parliament. The draft agreement represents one of the first times that a formal Reconciliation Agreement has been negotiated between a former colonial power and a former colony on a state-to-state level.

The genocide of the Herero and Nama began on 12th January 1904 after simmering tensions between German settlers and the residents of South West Africa with an attack by the Herero on German farmers and traders in Okahandja, Karibib, and Omaruru, with the primary aim of expelling the Germans from Ovahereroland. The Germans responded to this attack with massive brutality, murdering men, women and children.

An estimated 60,000 Herero and 10,000 Nama lost their lives at the hands of the German forces. It is not only about the number of lives lost, but also the social, economic and psychological impact.

The commander of the German forces, General Lothar von Trotha, issued an order on 2 October 1904 that amounted to an extermination declaration. Herero homesteads and cattle posts were attacked, and their residents annihilated. An estimated 60,000 Herero and 10,000 Nama lost their lives at the hands of the German forces. But as some of the victims of the genocide note, it is not only about the numbers of people lost but the social, economic, and psychological impacts that need to be considered.

The German forces attacked Herero who were gathered and seeking to negotiate a peace agreement at Omahakari (Waterberg) in central Namibia on 11 August 1904. Hundreds of Herero were killed outright, and many of those who escaped into the Omaheke Region to the east were hunted down and killed. An unknown number of Herero lost their lives due to thirst in their efforts to cross the Omaheke and flee into the Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana).

Annihilation, slave labor and destruction of their livelihoods

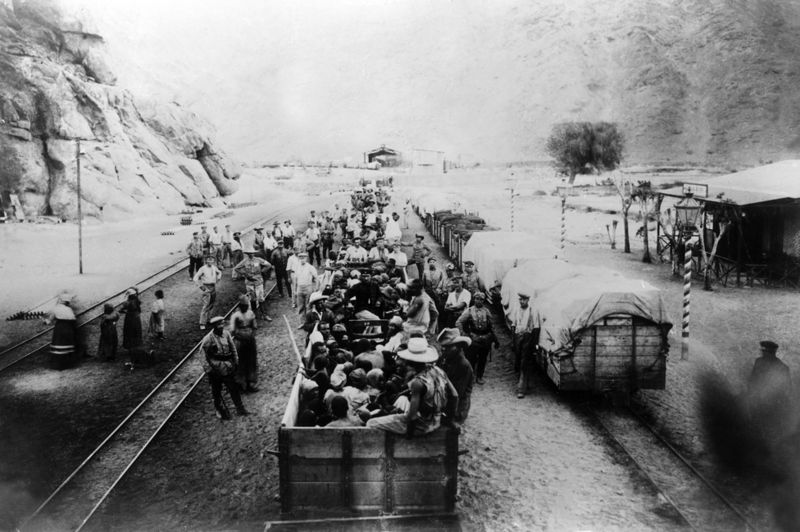

Outright massacres and murders of Namibia’s people by the Germans between 1904 and 1908 included not only Herero and Nama but also San and Damara. Thousands of Herero and Nama were confined to concentration camps where they experienced horrific living conditions, including lack of food, water, and medical attention. Others were forced into slave labor, building roads and railways, and working in mines and on German farms and ranches.

The genocide against the Herero and Nama had several phases. The first of these involved massacres of both combatants and non-combatants. The second phase consisted of the establishment of a cordon in the Omaheke region and hunting down and dispatching Herero refugees from the Battle of Omahakari. The third phase was the implementation of a scorched-earth policy aimed at destroying the livelihoods of the Herero and Nama; not only destroying homes, corrals, and sacred sites, but also capturing or destroying Herero and Nama cattle, goats and sheep and burning their crops.

The period between the cessation of formal war and the closing of the concentration camps in 1907-1908 did not see the cessation of hostilities, as the slaughter of Herero, Nama, and others continued until South African forces took over South West Africa and replaced the German colonial state in 1915. Although there was an overt effort by the German State to cleanse the archival records of evidence of genocide and massive human rights violations, efforts were made by victim groups to keep the knowledge of the first genocide of the 20th century alive and to commemorate the losses of Herero, Nama, San, Damara, and others.

Thousands of Herero and Nama were confined to concentration camps where they experienced horrific living conditions, including lack of food, water and medical attention.

One of the bitter reminders of the genocide was the presence of human remains of Herero, Nama and San in German museums, medical schools, and hospitals. Skulls, bones, and whole bodies were experimented on by German scholars over the next century. Some of the experiments were aimed at attempting to justify the racist scientific theories which underpinned German physical anthropological perspectives on race until the end of the Second World War and beyond.

In some cases, Herero and Nama human remains were put on public display in museums. There was a general outcry in the early part of the 21st century when the treatment of Herero and Nama remains became public, especially when stories were told of Herero women in the concentration camps at Luderitz and Swakopmund being forced to prepare the skulls of people who died in the camps for transport to German institutions.

There were some small measures of success, however, with, for example, Germany’s decision at the beginning of the 21st century to repatriate Herero and Nama skulls and other human and cultural remains to Namibia. The repatriation of these remains took place between 2011 and 2018 from German hospitals, museums, and other institutions. There were no formal apologies, however, for the ways in which the Herero and Nama human remains were dealt with while they were in German hands.

Seeking forgiveness without listening to descendants

On 14 August 2004, the German Minister for Development and Economic Cooperation, Heidemariee Wieczorek-Zeul, officially apologized at Omahakari, Namibia, for the atrocities that had been committed by German forces against the Herero and the Nama. Subsequently, other German government officials referred to the atrocities as a ‘genocide’ and sought forgiveness for their transgressions against the peoples of Namibia.

Germany negotiated only with the Namibian government in a series of meetings between 2015 and 2021 regarding how to handle the consequences of the genocide. There were virtually no negotiations with descendants of victim groups (the Herero and the Nama). Neither the Ovaherero Traditional Authority (OTA) nor the Nama Traditional Leaders Association (NTLA) were allowed to take part in the negotiations involving the reconciliation agreement.

Germany and Namibia provisionally signed an agreement that includes the payment of €1.1 billion over 30 years for development projects.

In May 2021, Germany and Namibia tentatively signed an agreement that includes the payment of €1.1 billion (US$1.3 bn) over 30 years for development projects in Namibia. The payment would be a kind of reconciliation fund that would provide financial, cultural, and other assistance to Namibia. The Herero and Nama rejected the financial offer as inadequate in public statements, but the Namibian government is considering accepting the offer.

The tentative plans of the Namibian government are to provide development assistance in 7 of the country’s 14 regions where the Herero and Nama represent a majority of the residents. There would be no payouts to individuals or communities, unlike, for example the recent reconciliation agreement of Australia, which has agreed to pay 75,000 Australian dollars (US $55,000) to some members of its Aboriginal population who were forcibly removed from their families as children.

No legal precedent, no land restitution

The draft Reconciliation Agreement stresses that Germany recognises the genocide in the moral and political sense. However, Germany’s position is that it has ruled out financial reparations to individuals for the genocide. What this means is that Germany does not want to set a legal precedent for paying reparations that might require the German government to provide financial compensation to victims of its colonial and post-colonial policies. Likewise, the agreement with Namibia can be a test case for future negotiations with the former French, British and Portuguese colonies in Africa.

One of the critical areas not mentioned in the Reconciliation Agreement was that of land, some of which is still in the hands of German Namibians. The Herero and Nama feel that land restitution should be considered in the Reconciliation Agreement, though the Namibian government has chosen not to support these requests. In 2020, Namibia issued a report on Ancestral Land Claims in the country in which it was argued that land could not be taken away from individuals who owned it without a ‘willing-seller-willing buyer’ agreement.

It remains unclear when Germany and Namibia will finalize the Reconciliation Agreement. What is clear is that the Herero and Nama and the San and Damara believe that the agreement does not contain the full range of what they feel they should receive in the form of reparations and compensation for the human rights offenses that they suffered –and continue to suffer– at the hands of the German colonial state. They feel strongly that the only way that reconciliation can be achieved is to have the descendants of victim groups participate fully in decision-making about how the gross human rights violations and their impacts should be addressed.

Robert K. Hitchcock is a professor of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico.

Melinda C. Kelly works at the Kalahari Peoples Fund.