‘I promised Brando I would not touch his Oscar’: the secret life of Sacheen Littlefeather

In 1973, she made history at the Academy Awards, appearing in place of Marlon Brando, declining his statuette and making a speech about Native American rights. She has been speaking out ever since

Sacheen Littlefeather begins by announcing that this will be one of her last interviews: “I’m very, very ill. I have metastasised breast cancer – terminal – to my right lung. And I’ve been on chemotherapy for quite some time, and daily antibiotics. As a result, my memory is not as good as it used to be … I’m very tired all the time because cancer is a full-time job: the CT scans, MRIs, laboratory blood work, medical visits, chemotherapy, infectious disease control doctors, etc, etc. If you’re lazy, you need not apply for cancer.”

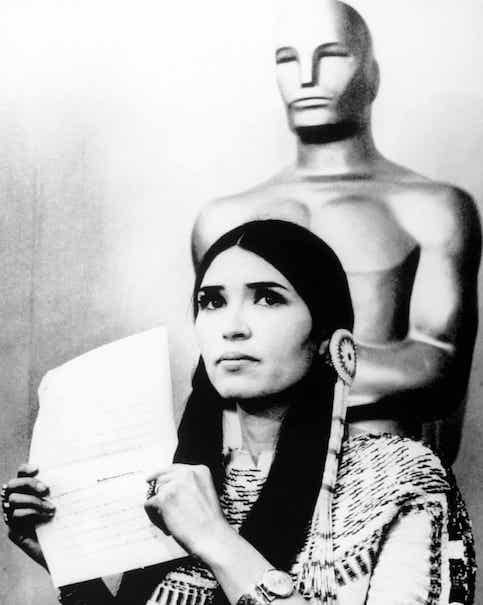

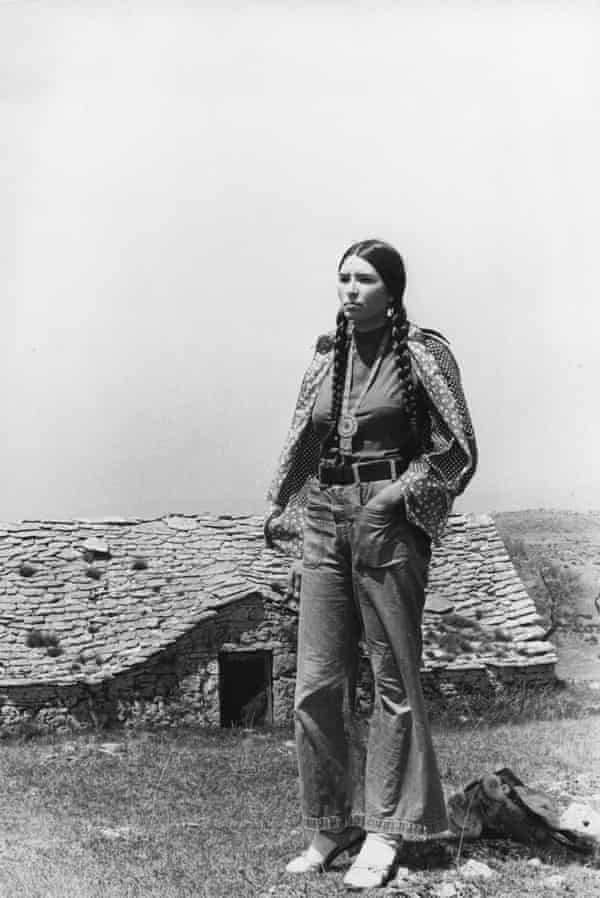

For the next couple of hours, speaking over Zoom from her home in northern California, as she trips down memory lane her solemn demeanour gives way to chattiness and laughter. At 74, she has lived a full, eventful life, though she will be for ever remembered for an event that took up little more than one minute of it, on the night of 27 March 1973. This was when she took the stage at the 45th Academy Awards to speak on behalf of Marlon Brando, who had been awarded best actor for his performance in The Godfather. It is still a striking scene to watch. Amid the gaudy 70s evening wear, 26-year-old Littlefeather’s tasselled buckskin dress, moccasins, long, straight black hair and handsome face set in an expression of almost sorrowful composure, make a jarring contrast.

When the presenter, Roger Moore, attempts to hand Littlefeather Brando’s Oscar she holds out her hand as if to push it away. She explains that Brando cannot accept the award because of “the treatment of American Indians today by the film industry”. The crowd interrupts her, half-applauding, half-booing. “Excuse me,” she says calmly, then continues: “And on television and movie reruns, and also with recent happenings at Wounded Knee.” At the time, Wounded Knee, in South Dakota, was the site of a month-long standoff between Native American activists and US authorities, sparked by the murder of a Lakota man. Littlefeather ends her speech begging that “in the future, our hearts and our understandings will meet with love and generosity”.

At the time, nobody knew what to make of it. Not the audience, the press or the 85 million people watching on television (this was the first year the Oscars were broadcast internationally via satellite). Was it a prank? A surrealist performance piece? Littlefeather was rumoured to be a hired actor, a Mexican impostor, a stripper. “It was not a performance, it was a real presentation,” she says. “I think that’s what took people by surprise: that it was so real. It really touches people’s hearts to this day.”

It was hastily planned, says Littlefeather. Half an hour before her speech, she had been at Brando’s house on Mulholland Drive waiting for him to finish typing an eight-page speech. She arrived at the ceremony with Brando’s assistant, just minutes before best actor was announced. Howard Koch, the producer of the Academy Awards show, immediately informed her she could not read it – and she would be removed from the stage after 60 seconds. “And then it all happened so fast when it was announced that he had won. I had promised Marlon that I would not touch that statue if he won. And I had promised Koch that I would not go over 60 seconds. So there were two promises I had to keep.” As a result, she improvised her speech.

However valid Brando’s charge of the way Hollywood stereotyped Native Americans, it did not go down well that night. John Wayne, serial slaughterer of Native Americans on-screen and self-professed white supremacist off it, just happened to be in the wings during Littlefeather’s speech. “During my presentation, he was coming towards me to forcibly take me off the stage, and he had to be restrained by six security men to prevent him from doing so.” Presenting best picture soon after (also for The Godfather), Clint Eastwood quipped: “I don’t know if I should present this award on behalf of all the cowboys shot in all the John Ford westerns over the years.” When Littlefeather got backstage, she says, there were people making stereotypical Native American war cries at her and miming chopping with a tomahawk. After talking to the press, she went straight back to Brando’s house where they sat together and watched the reactions to the event on television.

But Littlefeather is proud of the trail she blazed. She was the first woman of colour, and the first indigenous woman, to use the Academy Awards platform to make a political statement. Today they are almost expected, but in 1973 it was radical. “I didn’t use my fist [she clenches her fist]. I didn’t use swearwords. I didn’t raise my voice. But I prayed that my ancestors would help me. I went up there like a warrior woman. I went up there with the grace and the beauty and the courage and the humility of my people. I spoke from my heart.”

Littlefeather’s life up to that point had been difficult. Her father was Native American, a mix of Apache and Yaqui, and her mother was white. They met in Arizona – where mixed-race couples were still illegal – so moved to Salinas, California, working as saddle-makers and leather-stampers. “My biological parents were both mentally ill and unable to raise me,” she says. “I was a child who was abused and neglected. I was taken away from them at age three, suffering from tuberculosis of the lungs. I lived in an oxygen tent at the hospital, which kept me alive.” She was raised by her maternal grandparents, but saw her parents regularly. She recalls a time as a small child when she interrupted her father beating her mother – by hitting him with a broom. “I think that’s when I really became an activist.” Her father chased after her. “I escaped through a doorway and I ran with all my might down the road. And he got in the pickup truck, and he tried to run me over. There was a grove of trees. And it was near dark. I ran up a tree, and he couldn’t find me. I stayed up in the tree and I cried myself to sleep.”

Littlefeather was between two worlds. Since the late 19th century, there had been a concerted project in the US to “make Indian people white”, she explains, spearheaded by federal government and Christian schools for Native American children. “They wanted to make us something else. And this leads us into terrible pain, into suicide, into alcoholism, into jails.” She did not fit in at the white, Catholic school her grandparents sent her to. “There was a lot of racism. I was called the N-word.” When she was 12, she and her grandfather visited the historic Roman Catholic church Carmel Mission, where she was horrified to see the bones of a Native American person on display in the museum. “I said: ‘This is wrong. This is not an object; this is a human being.’ So I went to the priest and I told him God would never approve of this, and he called me heretic. I had no idea what that was.” In her teens, Littlefeather had a breakdown and was hospitalised for a year. She attempted suicide. “I was so confused about my own identity, and I was suffering,” she says. “I could not tell the difference between me and my pain.”

Fortunately, in the late 1960s and early 70s Native Americans were beginning to reclaim their identities and reassert their rights. After her father died, when she was 17, Littlefeather began visiting reservations in Arizona, New Mexico and California. She visited Alcatraz when it was occupied by Native American activists in the early 1970s. She travelled around the country, between camp-outs and pow-wows, learning traditions and dances, making outfits. “I really had a breakthrough, with other urban Indian people, getting back into our traditions, our heritage. The old people who came from different reservations taught us young people how to be Indian again. It was wonderful.”

By her early 20s Littlefeather was working as public service director at a San Francisco radio station, and head of the local affirmative action committee for Native Americans, studying representation in film, television and sports (they successfully campaigned for Stanford University to remove their offensive “Indian” sports team symbol). One of her neighbours was Francis Ford Coppola. “I used to hike the hills of San Francisco every day,” she says. “He’d be sitting on his porch, drinking iced tea.” She got to know him to say hello to. At the time, many celebrities were expressing interest in Native American affairs, including Jane Fonda, Anthony Quinn and Burt Lancaster. Sometimes it was sincere, at others more self-interested, she says. So, when she heard Marlon Brando speaking about Native American rights, “I wanted to know if he was for real”. She wrote a letter to him and, walking past Coppola’s house one day, said: “Hey! You directed Marlon Brando in The Godfather.” She asked him for Brando’s address. Eventually, Coppola gave it to her.

She heard nothing for months, but one night a man phoned her at the radio station. “He said: ‘I bet you don’t know who this is.’ And I said: ‘Sure I do.’ And he said: ‘Well, who is it?’ I said: ‘It’s Marlon Brando. It sure as hell took you long enough to call. You beat “Indian time” all to hell.’ And we started to laugh as if we’d known each other for ever.”

They talked for about an hour, she says, then called each other regularly. Before long he was inviting her to visit. She stayed with him several times. They became good friends, but were never lovers or romantically involved. “No, no, he was far too old for me. He was my mother’s age, for God’s sake! He was extremely intelligent, and always entertaining. He had a great sense of humour. He would put on tons of different voices. We used to have a great time, laughing till tears were coming out of our eyes.

The Brando household was a busy and often heated place – with children, ex-wives and girlfriends. Brando sent her and his girlfriend Jill Banner to go and see his latest movie, Last Tango in Paris – Bernardo Bertolucci’s controversially graphic erotic drama (which would earn Brando another Oscar nomination). Littlefeather was not shocked, she says. “I just thought that it was about a man who had a very difficult relationship with women. I thought about Marlon in his early days with his mother. It was as though his life was being played out in that film.” Brando, too, had had difficult parents: his father was disapproving and unloving; his mother an alcoholic. “When he was young, they didn’t have therapy. Maybe that was why he was such a great actor – because he worked it out in his acting. He was able to share those real emotions with an audience. And maybe that was the love-hate relationship that he had with acting.”

Littlefeather’s Oscar speech drew international attention to Wounded Knee, where the US authorities had essentially imposed a media blackout. It was a key moment in the struggle for Native American rights and may well have saved lives, she suggests. It did little for her own career, however. She had had a few small roles in movies, including Freebie and the Bean and The Trial of Billy Jack. After the Oscars, she believes she was blacklisted by Hollywood. “I couldn’t get a job to save my life. I knew that J Edgar Hoover had gone around and told people in the industry not to hire me, because he would shut their talkshow or their production down. I got the word from people in the industry that that would happen to them.” She is not sure it helped Brando’s career, either. “I was a hotbed of controversy. And for any actor, I don’t know how safe that is for them, box office-wise.” They stayed in contact for a little while, but their lives naturally went separate ways. “We had our time together. We made history together.”

A few years later, when she was 29, Littlefeather’s lungs collapsed – a consequence of her childhood tuberculosis – and she became very ill. She found taking a holistic approach to her health helped and did a degree in holistic health and nutrition. She became a health consultant to Native American communities across the country, combining her knowledge with traditional medicine. She also reconnected with the Catholic faith, working with Mother Teresa caring for Aids patients in hospices, and led the San Francisco Kateri Circle, a Catholic group named after Kateri Tekakwitha, the first Native American saint. Their religious practice is a synthesis of both traditions, she explains. “For example, we have our buffalo dances in the middle of the mass.” It has helped her resolve her identity. “This is how I saved my life, by blending the two together. The acceptance of my dominant culture’s ways and my Indian ways together, living peacefully side by side.”

Now she is one of the elders transmitting knowledge down generations. Littlefeather gestures behind her to the sofa, where she mentors young Native American people. This is the real fulfilment in her life, she says. “When I go to the spirit world, I’m going to take all these stories with me. But hopefully I can share some of these things while I’m here.” Littlefeather talks about the end of life with the same composure and dignity she exhibited that night in 1973. “I’m going to another place,” she says. “I’m going to the world of my ancestors. I’m saying goodbye to you … I’ve earned the right to be my true self.”