Indigenous Defenders Movement in Russia: A Briefing for Funders

1. Russia’s Indigenous Peoples

This briefing will describe the status of Russia’s Indigenous peoples and explore challenges facing the Indigenous defenders movement, its leaders, as well as other structural and institutional challenges. We will also discuss meaningful opportunities and principles for investment and international support for the movement.

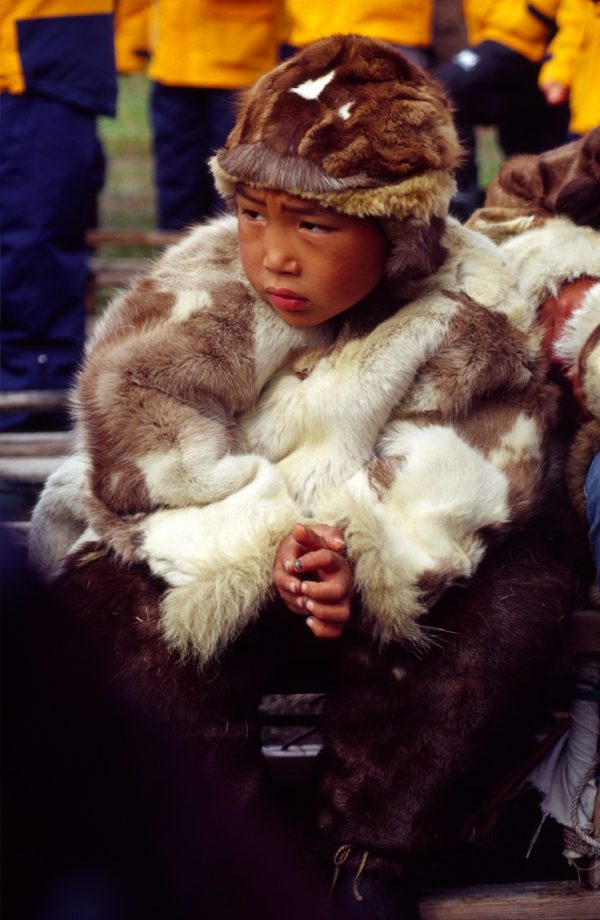

Russia is a multiethnic state of 145 million. While ethnic Russians account for four-fifths of its population, 160 ethnic groups make up the remaining 29 million. Among those, the most vulnerable are 40 “Indigenous Minority Peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East” [see box]. They sparsely occupy two thirds of Russia’s landmass, from Saami reindeer herders on the Kola Peninsula near Finland to Yupiq whale hunters in Chukotka, across the Bering Strait from Alaska. These peoples number about 260,000, just 0.2 percent of Russia’s population. While three-quarters of the mainstream population is urban, two-thirds of Indigenous peoples are rural, relying on subsistence activities such as fishing, reindeer husbandry, gathering, and hunting for food and income. Their languages, many of them close to extinction, are unrelated to Russian. At the same time, the industrial resource extraction that accounts for most of Russia’s revenues occurs on their ancestral lands, usually without their consent, and very often without their prior knowledge.

regions. Photo by Wolfgang Blümel.

“Small-numbered” peoples – by law, those under 50,000 in total population – are often distinctly more “Indigenous” than larger peoples: their traditional ways of life and subsistence strategies are more widely practiced and more central to their economy and culture. They also tend to be politically marginalised. Larger peoples such as Yakuts (Sakha), Buryats, Komi, and Altaians would qualify as Indigenous by international standards, but Russian legislation defines them as “peoples” and provides them with autonomous regions within the federation. Currently, however, their autonomy is largely symbolic.

While the population threshold can be a reasonable proxy for “indigeneity” in the Russian context, life is harder for Indigenous peoples like the Izvatas, a Komi subgroup practicing reindeer husbandry like their “small-numbered” Nenets neighbours, but without the same rights to land and resources.

History

Indigenous peoples in Siberia and the Far East first came under Russian rule with the conquest of Siberia in the 16th century. In the 20th century, seventy years of Soviet rule forced children into boarding schools, killed elders and spiritual leaders, and deprived communities of their languages, cultures, institutions, and spirituality, in part due to forced sedentarization and collectivization. The 1960s saw the start of Siberian oil and gas development, driving significant migration. Many Indigenous peoples have since become minorities in their ancestral lands.

Today, Article 69 in the Russian Constitution affirms a duty to protect Indigenous minority peoples, and three federal laws form a framework for protecting their rights, territories, and communities, although all are largely declarative and fall well short of international standards. The government sponsors events devoted to Indigenous cultures and languages, yet talk of self-determination and land rights is usually avoided.

Indigenous Rights Movement

Russia’s minority Indigenous peoples are fighting for rights to their traditional lands and resources, support for lifeways and spiritual beliefs, rights to self-determination, and basic human rights including clean water, education, and health care. Occupying challenging environmental and climatic conditions, each ethnos faces a unique set of challenges.

Yana Tannagasheva, a recently exiled Shor activist, says “If we are silent about violations today, we are stealing the future from future generations.” Yana advocates for the Shor people at a global level and has persuaded two United Nations committees to call for a complete restoration of Shor rights in Russia.

In 1990, Indigenous peoples formed a national umbrella organization, RAIPON (Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North). This organization and its many branches connected communities with state institutions and represented them internationally, including at the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues and on the Arctic Council. In 2013, the government overthrew RAIPON’s delicate balance by imposing new government-controlled leadership. As a result of this clampdown, a number of national and regional Indigenous leaders have fled Russia into exile.

In 2013 legislation was enacted on non-profit organizations, stipulating that non-profits receiving foreign funding and engaging in vaguely defined “political” activity must register as “foreign agents”. Since then over 150 NGOs, including Indigenous rights and environmental justice groups, have been registered and many have liquidated their organizations. Many organizations and individual defenders continue informally or in creative new forms (including “Friends of…” clubs, unregistered networks, and even as businesses or publishing houses), but operate with less financial support or vital public awareness of their work.

Indigenous organizations are generally subject to even closer scrutiny and distrust than civil rights groups. For the Russian government, the Indigenous rights movement is “worrisome” for several reasons: fear of demands for true self-governance or even full independence in some cases, and Russia’s almost total economic dependence on resources extracted from traditionally Indigenous lands.

In response, 40+ experienced Indigenous defenders have established a new network known as “Aborigen Forum,” an intentionally informal and agile network which unites Siberian and Far Eastern leaders, giving them an advocacy platform and restoring the flow of information. The Forum’s mission is to protect and realize the rights of Indigenous peoples through legislation, monitoring, partnerships, and dialogue with government.

Pavel Sulyandziga, an exiled Udege activist and and former RAIPON vice president comments, “Internationally, Russia is a dangerous and influential player when it comes to trade agreements and strategic resources, and nations seeking to avoid conflict often ‘overlook’ the rights of Russia’s Indigenous peoples.”

2. Challenges for Indigenous Defenders

Today, Russia has several generations of experienced Indigenous defenders and community leaders, skilled in advocacy and engagement both at home and abroad. Their activism has halted some of the most harmful projects including large hydroelectric dams in Evenkia, Amur, Yakutia, and near Lake Baikal, aided the creation of Bikin National Park which enshrines Indigenous co-management for the Udege people, and kept a Khanty shaman and defender of a sacred lake out of jail in his case against an oil company. Indigenous defenders have brought global attention to many more local conflicts and received broad recognition as equal partners in UN climate negotiations and many other fora. Every year, young Indigenous activists participate in human rights trainings at the UN and join the global Indigenous movement.

They achieve these successes despite a multitude of structural and individual challenges as well as administrative isolation and government limits on freedom of movement for remote Indigenous communities, both of which limit interaction with the larger world.

Let’s examine a few of them here.

Data access: No official disaggregated data is available on the socio-economic state of Indigenous peoples: for example, there is no way to determine the life expectancy of Evenks or the median income of Nenets. As a result, efficacy of policy measures cannot be evaluated or provide accurately for Indigenous peoples. Lack of data also has local impacts: administrations are ignorant of the identities of actual land users when signing over land to extractive companies, and communities struggle to access mandated corporate documentation and environmental monitoring data. On the plus side, many Indigenous communities have become quite skilled in land-use and resource mapping as well as community-led monitoring.

Information access: Corporate and government claims that Indigenous communities have given free, prior, and informed consent to a project are difficult to verify, and international investors usually accept such claims without verification. Outside of urban centers, information about communities rarely reaches the outside world, leaving them vulnerable to pressure and threats. Newspapers, TV, and radio stations are typically in lockstep with government. Where available, internet access is expensive and strong research skills are needed to access information. In Russia, while many environmental and social justice activists speak English, Indigenous defenders often have weak or non-existent English skills, an added barrier.

Threats to individuals: The safety, freedom, and reputations of Indigenous defenders in Siberia and the Russian North are under threat from many sides, and activists have been jailed on fabricated or flimsy charges, fled the country, or intimidated into silence. Other frequent forms of harassment include threats against family members, especially children, and removal of passports by a variety of means, including judicial. Activists can lose their economic security: laid off their jobs in the dominant public sector and then unable to find new employment. Foreign allies can be deported or denied entry for minor regulatory offenses, and security services excel in exploiting immigration regulations.

Basic freedoms persist: While new laws have been enacted that curtail rights. Russian citizens still have significant freedom of expression. In fact, determined citizens can reach a wide audience, argue persuasively for their rights, achieve legal victories, and change the situation on the ground. Indigenous rights activists maintain strong relationships and engagement with global activists and in international processes and human rights mechanisms.

3. Regional Advocacy

Yamal and LNG: The Yamal Peninsula is the home of the world’s largest nomadic reindeer herding community, with several thousand Nenets roaming the tundra with their herds. Yamal LNG is a 27 billion dollar gas extraction project taking place there. With backing from the Russian government and foreign extractive corporations, Yamal LNG claims to have obtained to the Nenets’ free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC), extremely difficult to verify, since non-residents cannot visit without government security (FSB) permission. Evidence from a fact-finding mission suggests, however, that no genuine FPIC process could have taken place and that the disruption of migration routes, impacts on fish reserves, and pasture lands will force a substantial share of reindeer herders in the region to give up their way of life. Such conflicts between hunting and herding peoples and extractive industries are common: Komi Republic, Yakutia, Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Area, Taimyr, and Sakhalin Island, just to name a few.

Destroyed Communities: The Shor people of Siberia’s Kuzbass region have survived a string of forced resettlements since the early 1970s, always for the same reason: open cast coal mining. They never received compensation or any redress for the loss of their hunting grounds, sacred sites, pastures, and rivers. In 2015, the Shors submitted a complaint to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), which in 2017 called for fair redress for the evicted community – a tremendous victory! Russia is considering its response to CERD, and a wave of anti-coal protests is now sweeping the region, capturing global attention.

Right to subsistence: For most Indigenous peoples in Russia, the staple traditional food source is fish. According to federal legislation, Indigenous peoples have the right to traditional fishing without permit or imposed limits. In reality, much Indigenous peoples’ fishing is caught up in a bureaucratic jungle. Often Indigenous people are unfairly targeted and fined for violations, and their gear confiscated or destroyed, leaving them a choice between starvation or “poaching” on their own river, while commercial fishing companies harvest fish on a massive scale, secure in their government-approved monopoly. Indigenous defenders battle for their rights and existence, river by river, hunting territory by hunting territory, holding their ground wherever possible.

Gennady Shchukin, a Dolgan leader from the Taimyr Peninsula, where Indigenous communities who engage in traditional hunting have been criminalized as poachers, says: “Our Indigenous communities here struggle for hunting rights as part of our traditional way of living. We are determined to bring this struggle to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, if necessary.”

There are many parallels for Indigenous communities reliant on hunting and gathering (for example, Siberian pine nuts). In these cases, Indigenous communities lose out to commercial logging, commercial pine nut harvesting, land developers, and even private citizens after recent creation of a program awarding a “free hectare” of land to almost any applicant in the Far East, including within regional Indigenous “Territories of Traditional Natural Resource Use”. The Aborigen Forum, mentioned above, has protested many of these problems through appeals and community-to-community outreach and, together with their allies, managed to prevent the worst.

4. How Funders Can Engage

Although the situation in Russia is quite challenging, there are still significant opportunities to support Indigenous defenders. It is critical that international civil and Indigenous rights activists and donors continue to engage in Russia with direct support, technical expertise, capacity building, and access to international information channels and treaty bodies. Last but by no means least, Russian defenders depend on the international community to witness and testify to their struggles. Activists can and will work in isolation, but their efforts have greater potential for success in strategic partnership with and support from the international community.

As Russia is not a “developing nation”, its Indigenous peoples have no access to international development funds, although their conditions are often similar to those in developing countries. In recent years, international support has faded, as many funders have either naturally cycled out or discontinued their support due to security concerns. Domestic Russian funding for Indigenous rights work, such as the “presidential grants” program, is mostly awarded to ”obedient” groups working on uncontroversial topics.

It is quite possible to build strong and effective partnerships with Indigenous defenders in Russia, while minimizing risk. For example, IWGIA has decades of stable relationships with Indigenous networks and organizations. Their support was pivotal in developing the capacity of several generations of Indigenous activists, providing resources, and facilitating use of international human rights mechanisms. A few other organizations, including Global Greengrants Fund, The Altai Project, and Pacific Environment, have strong networks and regranting expertise in Russia’s environmental and Indigenous movements.

- Thoughtful relationships

- Ask potential partners about how they assess and manage risk. Avoid paternalistic decision-making and seek out Indigenous-led initiatives.

- Consult with stakeholders including relevant foreign Russian-speaking experts.

- Follow your partner’s lead on publicity to protect their reputation and safety; consider increasing digital security.

- Flexible and opportunistic

- Seek creative funding paths, consider using an experienced intermediary organization with Russian language capacity and grants administration experience in Russia, make specially-structured grants to individual activists, etc.

- Expect the unexpected; laws and power structures change, but there’s always a way!

- Help partners be opportunistic and allow for midstream changes.

- Sometimes NOT losing ground is success; limit expectations and metrics. Keep the home fires burning in Russia’s Indigenous defenders movement.

- Promote connection at home and abroad

- Strengthen international connections, including access to international justice mechanisms.

- Support informal networks, meetings, and exchanges – vital tools for propagating information and strategy.

- Knowledge is power – knowledge of UNDRIP rights, FPIC, international standards, and success stories in other countries is extremely valuable.