The Amazon is Dirty, Our Rivers and Fish are Contaminated, Everyone is Sick

“The Amazon is dirty, our rivers and fish are contaminated, everyone is sick. We no longer feel safe in the forest, in our home.” — Alessandra Munduruk, Munduruku Mother

The Yanomami, Munduruku, and Kayapo Peoples share how the Bolsonaro government is worsening their situation and threatening the forest and human rights in Brazil in this three part article series. Part one focuses on Yanomami Peoples.

At the beginning of December 2020, Brazil’s Congresswoman Joenia Wapichana, the Joint Parliamentary Front in Defense of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the Parliamentary Environmental Front organized a webinar with politicians and civil society to hear testimonies of three Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon on their current realities.

After the event, I connected with members of the mentioned Peoples who shared more in detail about what is happening on the ground in Brazil. One of the speakers connected me with the public prosecutor, the equivalent of a district attorney, who divulged important documents about illegal mining activities on Yanomami lands.

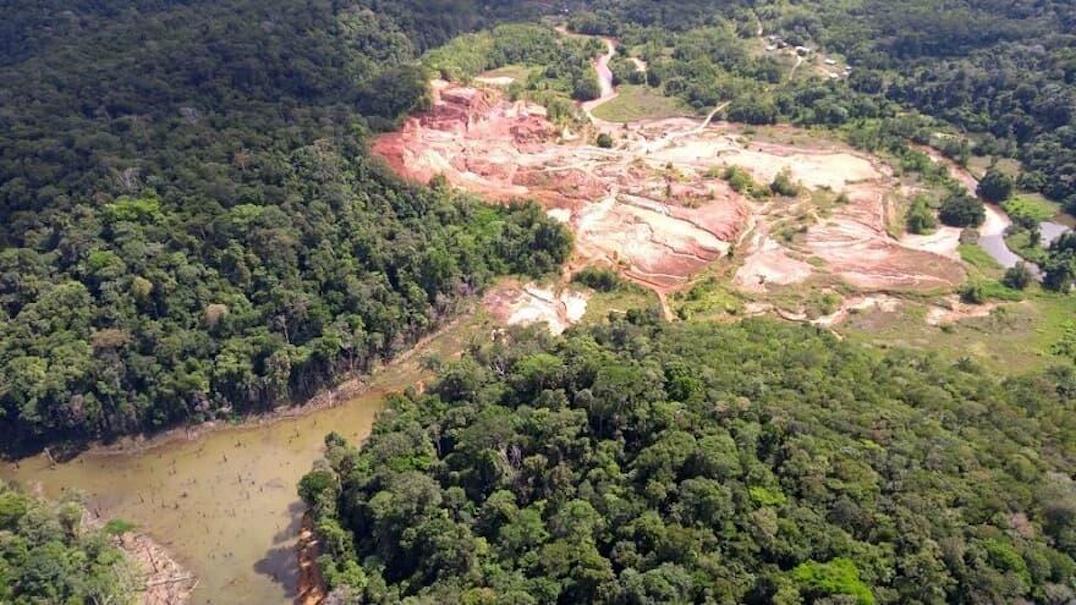

This article focuses on five issues related to the violation of Indigenous Peoples’ rights and the destruction of their lands in the Brazilian Amazon: the invasion of Indigenous lands; the contamination of soil, rivers, fish and communities with mercury; diseases and health problems, such as infertility, resulting from malnutrition; high consumption of drugs and alcohol, brought by prospectors, affecting Indigenous communities; dismantling of agencies and institutions that protect forests and Indigenous communities, such as local Indigenous health posts, environmental protection bases, and policing and monitoring of territories.

The Yanomami Report

The small Yanomami village of the Kayanaú community, near the Mucajaí River in the Rio Negro basin, numbers about 200 people who are dealing with a contingent of more than 1,600 illegal prospectors on their lands.

An airstrip for small aircrafts was built in their territory in the state of Roraima, the country’s far north region bordering Venezuela. The track that once received health personnel and environmental and border protection agencies was taken over by illegal miners. The frequency of flights of airplanes and helicopters to supply the mine is now more than 50 per week. This heightened number has alerted the team of healthcare officers who visited the Indigenous community during a health and vaccination check in. The planes bring more prospectors, alcoholic beverages, and even drugs to the site weekly. Not only do they land with their fleet, but miners wander around the villages in armed groups, travel the rivers by boat, and settle in strategic places to establish illegal mining sites. These people not only offer Yanomami goods and money, disrupting their traditional economies, but also introduce individuals to drugs, alcohol, even prostitution to coerce the local community as a labor force. Without legal, environmental and even special protections such as consent protocols, State monitoring, and insufficient healthcare, the negative impacts on the Indigenous livelihoods are quickly felt.

The medical team and the prosecutor who are monitoring the situation without resources told me that they found “Indigenous people constantly drunk and that women, children, and adults walk through the woods with alcohol at all times. That’s why they’re refusing medical treatment.”

In addition, the practice of semi-slavery of Indigenous Peoples in the region is prevalent, because, after creating drug and alcohol dependency, the community no longer wants to practice traditional activities, such as agriculture, hunting, and gathering. In exchange for drugs, alcoholic beverages, and prostitution, they go to work for the prospectors. The medicine, vaccinations, and resources intended for the Yanomami were taken by the miners, leaving the Indigenous People completely unprotected, sick and vulnerable.

Moreover, the situation is even more alarming with regard to violence at various levels. The monitoring medical team is afraid of retaliation and threats from prospectors if they release their report which shows how the miners, employed corporations whose names and affiliations are never revealed, install a structure of scaffolds along the rivers, to support and protect their illegal activities. The region has been abandoned by the State.

Dário Kopenawa, son of prominent Indigenous leader, thinker, and author of The Falling Sky – Words of a Yanomami Shaman, David Kopenawa, reveals that, despite all the visibility that the Yanomami people have, the Brazilian government has done nothing to stop the invasions and illegal mining on their lands. Yanomami associations are raising the visibility of this issue and have collected more than 439,000 signatures from people in Brazil and abroad in a petition demanding the removal of 20,000 illegal prospectors in the Yanomami territories.

The mining, beyond causing the degradation of rivers and forests, and undermining the rights and protections of Indigenous Peoples, has caused serious health issues for communities near and far. The miners, prospectors and their entourage are the main sources of transmission of the new coronavirus, and other diseases, such as STDs, and the flu. A total of 1,202 Yanomami were infected by COVID-19 and 23 have died, according to a report produced by the Yanomami and Ye’kwana Leadership Forum.

The lands of the Yanomami are located in two states in the north of the country, Roraima and Amazonas. They are neighbors to the territories of the Munduruku and Kayapo Peoples, who are also facing a systematic invasion of their lands and are endangered by genocide and unprecedented environmental impacts.

The Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information, or Raisg, in their report entitled Looted Amazon (Amazonia Saqueada), shows that there are more than 2,500 mining sites in the Amazon region, comprising areas in Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela. The report also shows the general routes going in and out of mining areas in the region as well as the impacted rivers and Indigenous lands by illegal practices.

If a mining station accommodates an average of 1000 people, it is not difficult to conclude that the Amazon today has never been more in danger. With the high price of gold on the international market, the practice of mining has intensified even more during the COVID-19 pandemic, which in turn increases the human rights violations against Indigenous Peoples.

Given this situation, protection agencies as FUNAI, the federal police, and IBAMA– the federal agency of monitoring and protection of the environment, have seen their budgets cut dramatically. In the case of FUNAI, its mission has been changed profoundly, “from an Indian affairs agency to a State agency against Indigenous Peoples,” as described by Alessandra Munduruku, a Indigenous activist from Munduruku people.

In addition, the Brazilian government has insisted on implementing unconstitutional laws and influencing public opinion to serve the interests of mining companies. According to the website Amazonia Legal and E. de Sao Paulo newspaper, a survey reveals that 145 applications for mining permits were filed with the National Mining Agency by November 3, 2020, the highest volume in 24 years.

A bill formulated by Brazilian President Bolsonaro in February 2020 aims to legalize mining activity on Indigenous lands and is currently sealed by the Brazilian Constitution. In September, the government launched the Mining and Development Program, which cites its goals as “promoting the regulation of mining on Indigenous land, granting of mining titles, stimulating the implantation of mining sites, and fostering geological research of mineral goods considered a priority for the country.”

Despite being unconstitutional, the National Mining Agency (ANM) maintains the requests of more than 3,000 applications to mine on Indigenous lands (IT) in the Amazon, as the Looted Amazon report reveals. Any mining activity, even research and prospecting, is prohibited by Brazil’s Constitution in these areas, but Indigenous Peoples have witnessed that leveraged by the federal government, every month, dozens of new requests are filed and accepted. All these actions multiply the problems that Indigenous Peoples in Amazon are facing.

On the day before Christmas, the Coogal Union of Miners in the north of the country in Lourenço, a region near Roraima and Para, where the Yanomami, Munduruku and Kayapo Peoples live, managed to reverse a court decision on the suspension of old extraction activity as well as the dissolution of the entity for its illegal and risky activities. However, the judge of TRT-8, the regional labor court, Luís Ribeiro saw serious social impact implications to families living in the region. The Union has more than 900 members whose families also live in the area. This is yet another example of how the situation, unresolved by the government, creates an avalanche of social, environmental, and legal problems.

In June 2020, representatives of Yanomami associations organized a conference with the Vice-President of the Republic, Hamilton Mourão, with Congresswoman Joenia Wapichana. He received the document with evidence of the illegal mining activities and a formal petition for the removal of the miners. According to Dario Kopenawa, Vice-President Mourão said, “Ah, Dario, the Yanomami territory is very large, the federal government does not have the resources to pay employees, has no planes, logistics are difficult [to protect the area]. I worked in São Gabriel da Cachoeira, I know the region.”

Then, on his Twitter account, the Vice-President said that the number of prospectors on Yanomami lands is 3,500 and not 20,000, as estimated by Indigenous organizations. This attitude of disrespecting Indigenous Peoples and trying to delegitimize their cause has been commonplace in the current administration. Still, the second man in the government has promised a plan to remove illegal prospectors from Indigenous lands. So far, nothing has happened.

This situation is not only an example of the problems faced by Indigenous Peoples, but the Brasileiro State, in its deadly incompetence, does not offer environmental protection, prevent social and cultural conflicts in the region, or guarantee a healthy environment for vulnerable citizens. The rights to life, integrity, culture, property, freedom, according to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, through Consultative Opinion (OC) 23/17, has a strong interdependence with the environment environment and sustainable development, in other words, that human rights are fully satisfied only if a “minimum environmental quality” is respected.

Indigenous Peoples in Brazil want the world to know that their rights are being violated on their own territories. The Brazilian State is violating their rights to a healthy environment and therefore their rights to to life, health, food, water, sanitation, property, private life, culture, and non-discrimination, among others. There is a profound relationship between the rights of Indigenous Peoples and the rights of Nature and its protection. The destruction of such a large area, larger than many countries in Europe, has a significant impact on the environmental relations on the planet, worsening the effects of climate change which affects everyone, Indigenous or non-Indigenous.

A fighting generation of the Yanomami, as well many Indigenous Peoples in Brazil, have suffered devastating losses in 2020 due to COVID-19. “Our Grandmothers are dying. We want to live in peace. We want our land in peace, without the presence of prospectors. Our relatives, the fish and animals are dying of mercury. Our land is already demarcated. The Constitution has very beautiful words about our rights, but in practice this is not what happens,” concludes Dario Kopenawa.

The request is simple and clear: “Remove Miners from Our Lands!”

— Edson Krenak Naknanuk is an Indigenous activist and writer in Brazil and a consultant at Cultural Survival. Currently, he is a Ph.D. candidate in Social and Cultural Anthropology with studies in Legal Anthropology at Vienna University, Austria. He is also a teacher of languages and humanities. He loves interacting with children and youth and preparing them for a better world.