Why protecting Indigenous communities can also help save the Earth

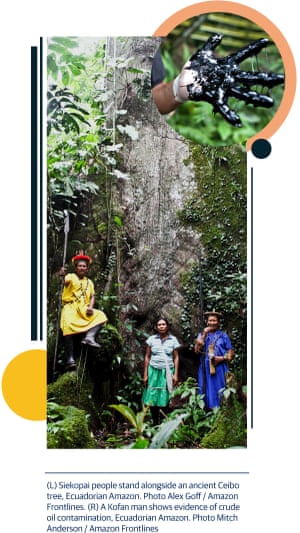

For thousands of years, Indigenous communities have been caretakers of the environment, protecting their lands, respecting wildlife and utilizing traditional knowledge passed down through generations.

Today, they continue to safeguard some of the most biodiverse areas on the planet. Almost 50% of the world’s land mass (minus Antarctica) is occupied, owned or managed by Indigenous peoples and local communities, with roughly 40% of those landscapes labeled as protected or ecologically sound. And though Indigenous peoples comprise only around 6% of the global population, they protect 80% of biodiversity left in the world. Preserving biodiversity is also key to turning around the climate crisis, as these areas are major carbon sinks.

At the same time, many Indigenous communities – especially those in isolated regions – continue to face threats like disease outbreaks, poverty, environmental injustices and human rights violations. Some rural populations may even be facing extinction: one 2016 study followed eight Indigenous groups living in isolated areas in South America over the course of a decade, and found only one group to be growing, while the rest were small and sparsely populated.

“As go our peoples, so goes the planet,” says Nemonte Nenquimo, a leader in the Waorani community in Ecuador and founding member of Indigenous-led nonprofit organization the Ceibo Alliance. “The climate depends on the survival of our cultures and our territories.”

PROTECTORS OF THE PLANET

Growing up in the rainforests of Ecuador, Nenquimo deeply respects the flora- and fauna-rich land. Waorani territory spans 2.5m acres and is home to 800 species of animals and birds, many of which are endangered. The forest also acts like a natural pharmacy, producing plants with medicinal properties that can treat everything from wounds to snake bites. One Waorani discovery called curare, a plant extract traditionally used to make poison darts, was developed into a muscle relaxant now popularly used in anesthesia.

Beyond being one of the most biodiverse regions on Earth, the Amazon rainforest generates more than 20% of the world’s oxygen. Tropical forests also help slow climate change by acting as giant carbon sinks that absorb and store excess CO2 from the atmosphere. Right now, trees in these forests store roughly 250 billion tons of carbon, although capacity is decreasing as rainforests are continuously depleted, notes a March 2020 study.

- (Center) A Waorani elder stands alongside a gas flare near an oil refinery some 32 kilometers (20 miles) from the Amazonian city of Lago Agrio, Ecuador. Photo Mitch Anderson / Amazon Frontlines

Yet, for many years, the Waorani people have had to fight against destructive activities like oil drilling, deforestation and industrial-scale agriculture.

“Our brothers and sisters living in isolation have made the decision to live in the way of their ancestors, but the world is closing in on them,” says Nenquimo. And now, the coronavirus pandemic is threatening the livelihood of Indigenous communities like her own. “The global economy continues to drive poachers, loggers and land grabbers deep into our territories, putting our peoples at risk.”

Advocates like Nenquimo continue fighting to conserve their land. Teaming up with nonprofit organization Amazon Frontlines, the Ceibo Alliance is already paving the way for change after winning a historic legal battle in which the Ecuadorian government passed a ruling protecting 500,000 acres of the Amazon rainforest. Plus, they also set a legal precedent to protect an additional 7m acres from being auctioned off to oil companies.

While Indigenous communities continue to step up for the planet, they can’t do it alone. “We are all in this together. We need the world to recognize this,” says Nenquimo. “This isn’t about Indigenous peoples fighting heroically and risking our lives to protect the land. This is about us all joining together across cultures, races and classes to change the way our global system works.”

One such organization taking action is One Earth, a philanthropic initiative that aims to mobilize capital to solve the climate crisis and keep the global average temperature below 1.5°C. Co-founder and executive director Justin Winters says with every tenth of a degree the temperature rises, the closer the globe is to spinning out of control and launching into what scientists have dubbed the sixth mass extinction.

A key tenet of One Earth’s strategy to curb warming is to restore and protect 50% of all land and seas. “Many people today lack an understanding of our reliance on Earth, its vast biodiversity and ingenious, brilliantly designed systems that have evolved over millions of years to support life,” says Winters.

We have a lot to learn from those who do understand the symbiotic relationship between humans and the earth, Winters says, and we can’t protect the planet without the traditional knowledge and sustainable agriculture practices of Indigenous peoples living in these areas.

“There are leaders like Nemonte all over the world who are fighting hard to protect their lands, their waters, their families, their future – their home,” Winters says. “We have underestimated the power and importance of frontline communities and nature for far too long.”

“The Earth is our teacher, and we are listening to her,” says Nenquimo. “Because Indigenous peoples are so close to the land, we also have a lot to teach the rest of the world about respect for the Earth, and about spirituality and reciprocity.”

HOW A GLOBAL SAFETY NET CAN ENSURE A BETTER FUTURE

As a growing swell of scientific research highlights the integral role Indigenous communities play in environmental conservation, new technologies are emerging that will help to protect them and the regions they care for. One such innovation is the Global Safety Net, a “blueprint” to restore our biosphere, rebalance the global climate system and help prevent future pandemics. The two-year research effort mapped all lands of importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, and determined how these lands can be woven back together through a network of corridors, restoring 350 mega-hectares of degraded land.

“The Global Safety Net is the first ever spatially-explicit framework that highlights sites of particular importance for both biodiversity conservation and carbon storage,” says wildlife scientist Eric Dinerstein, director of Biodiversity and Wildlife Solutions at RESOLVE. “It’s a dynamic tool designed to support multilateral, national and subnational land use planning efforts to save life on Earth.” With the overall goal to overcome climate change and restore the natural world, the Global Safety Net aims to prevent a sixth mass extinction event by making our ecosystems more resilient as the planet warms.

- Using global biodiversity and carbon spatial data, the Global Safety Net identifies terrestrial areas where expanding protection to approximately half the Earth can reverse biodiversity loss and stabilize the climate. Shown here is a visualization of Africa and Europe.

The Global Safety Net also recognizes that supporting Indigenous communities is critical to achieving these benchmarks. “We found that addressing Indigenous land claims, upholding existing land tenure rights and resourcing programs on Indigenous-managed lands could help achieve biodiversity objectives on as much as one-third of the area required by the Global Safety Net,” says Dinerstein.

Based on Dinerstein’s research, he says an additional 35% of land areas need to be protected in order to preserve the environment and stall climate change. “Stabilizing the climate and reversing biodiversity loss are interdependent; we cannot achieve one goal without accomplishing the other,” he says. “This must be done within the next decade. The level of planning and foresight needed to properly scale nature conservation requires the emergence of a worldview that embraces the notion of stewardship at a planetary scale.”

IT’S NOT TOO LATE. HERE’S HOW YOU CAN HELP

Reversing climate change is a massively complex and overwhelming task. And with the deluge of depressing headlines dominating the news cycle, it’s easy to feel hopeless about the future. “Some people question whether it’s still possible to solve the climate crisis,” Winters says. “One of the central and often overlooked solutions to climate change is protecting nature.”

Already people are taking action, and we’re seeing results. Countries are shutting down coal-fired plants. Many governments have committed to zero carbon emissions. Wind and solar power are quickly becoming some of the least expensive forms of electricity in the world.

At the same time, Indigenous peoples’ contributions to conservation are being increasingly recognized. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was adopted in 2007, and remains one of the most comprehensive international declarations protecting Indigenous rights today. In 2016, the American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was adopted. Two years later, the Green Climate Fund adopted the Indigenous Peoples Policy, which recognizes and assists fully engaging Indigenous communities in decision-making related to their land and reducing global warming. And of course, Nenquimo and her fellow advocates’ recent victory securing the protection of 500,000 acres of rainforest is a huge step forward.

When it comes to making an impact yourself, there are many ways to get involved. On a local level, Dinerstein invites people to explore the Global Safety Net app, created in partnership with Google, and find important ecosystems in their local region to support. Replacing lawns with small native wildflower meadows or miniature forests are great ways to help nature, with advocates finding such forests to store up to 40 times more carbon and increase biodiversity by 100 times.

People can also practice conscious consumerism and reduce their carbon footprint by walking, biking and using public transportation, as well as cutting back on meat consumption and only buying products that are sourced sustainably. Get active on the political scene: help change legislation by signing petitions, switching banks and voting for leaders who recognize that we must preserve biodiversity if we want to make it as a species.

- (L) A Kofan woman from the community of Sinangoe celebrates her people’s historic legal victory against gold mining, Ecuadorian Amazon. Photo Jeronimo Zuniga / Amazon Frontlines

We must also recognize that Indigenous peoples are more than just victims in the destruction of their territories. Across the globe, Indigenous communities are quite literally our last line of defense to save the biosphere upon which we all depend. Their land stewardship, moral principles around leadership and relationship with the surrounding ecosystems is what we need to learn from and act upon. Supporting Indigenous-led organizations is especially important, as they could help drive rapid conservation of both land and sea.

Winters adds that you can volunteer or donate to initiatives working on the frontlines – like Amazon Frontlines and the Ceibo Alliance – or contribute to international environmental organizations, including the Rainforest Alliance, Rainforest Action Network and many more. Support calls to action, like the Global Deal for Nature, which calls upon world leaders to establish ambitious goals that both protect nature and restore Indigenous lands for the upcoming UN Convention of Biological Diversity. And, be sure to vote for leaders who advocate for renewable energy and preserving natural land.

“With the power of collective action fueled by optimism, we can do this,” Winters says. “It’s vital that we know it’s achievable and we are motivated to work together to create a future we want.”