The scarred landscapes created by humanity’s material thirst

The world’s desire for electronics, fuel and geological riches is etched in devastating shapes and colours all over the globe. In the latest of BBC Future’s Anthropo-Scene series, we show the striking ways that mining has rewritten the surface of the Earth.W

When we dig to extract a precious metal, a carboniferous fuel, or an ancient ore, we remove a chapter of another time. Such materials are, in the words of the writer Astra Taylor, the “past condensed”, telling of epic eras of magmatic fury, tropical forests or hydrothermal steam. They take millions of years to settle or crystallise, then only moments to remove with machinery and explosive.

Ever since humans first realised that the ground beneath them held hidden riches, we have dug down to discover what lies beneath. Mining makes almost every aspect of our modern lives possible, and often the effects on the natural world are far, far away from home.

When you see the impact of a mine visually, it can subtly change how you think about your possessions. Even these words are delivered via geological materials – behind this screen, enmeshed in electronics, there are metals that were once locked for millennia within rock. And somewhere in the world right now, our desire for more and more this technology is fuelling ever-deeper and broader subterranean searches for those resources.

Below, we look at the myriad ways that mining has transformed the surface of the Earth – whether it’s the striking, unnatural hues of “tailings ponds” or the open-cast landscapes that look like the fingerprints of humanity itself. If the ancient ores and minerals we covet are the condensed past, then sadly what is in store is a scarred future.

Welcome to “Anthropo-Scene”, a new BBC Future series. By looking through a lens at far-flung places around the world, our goal is to compile a definitive photographic record of how humanity is reshaping our planet and nature.

One of the largest mining pits in the world, with 84 types of minerals, is the ‘No.3 pegmatite’ in Xinjiang, China (Credit: Shen Longquan/ Getty Images)

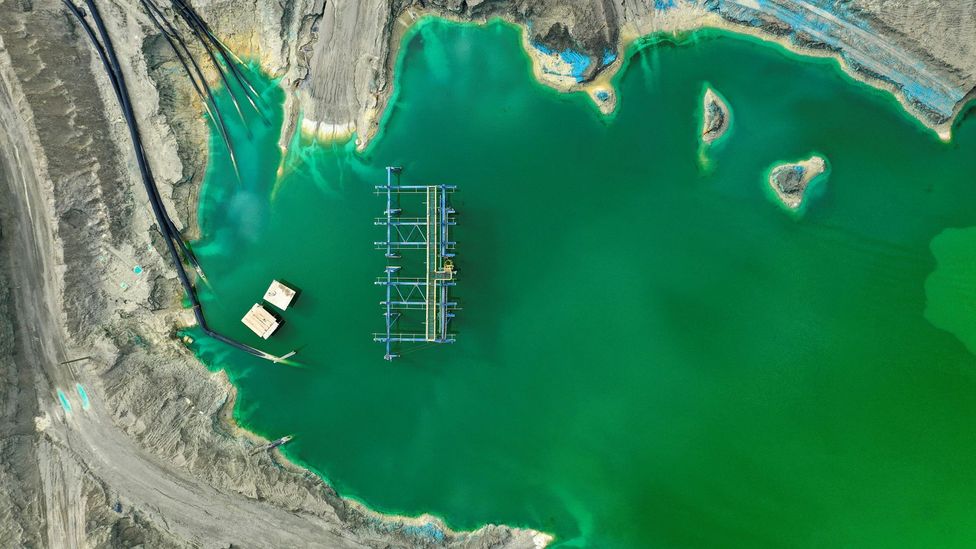

China’s Emerald Lake, in the Qinghai province, is an abandoned mining zone (Credit: Getty Images)

There, historic mining left behind salt and other minerals in giant ponds with a greenish hue (Credit: Getty Images)

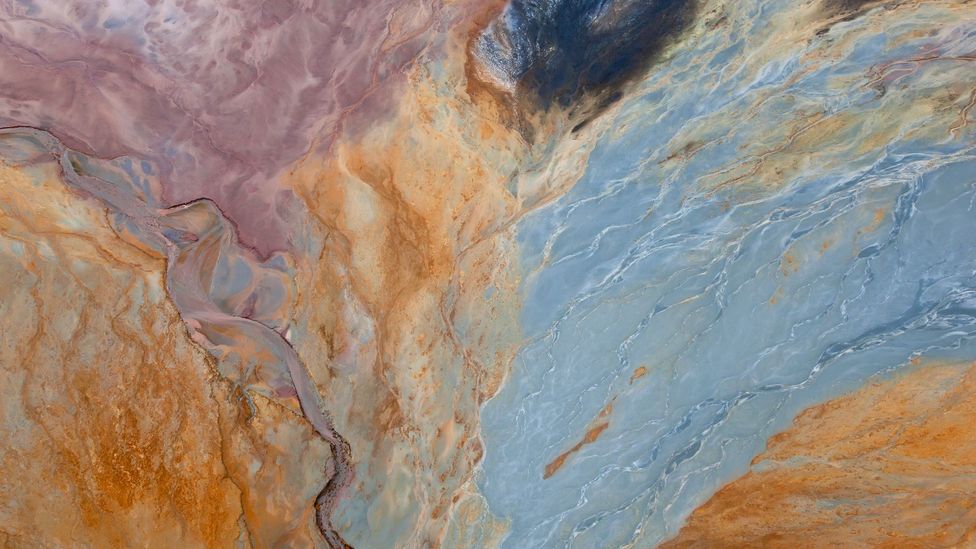

Oxidised iron minerals in the Rio Tinto mining area of Huelva province in Spain (Credit: Peter Adams/Getty Images)

Mixed with water, the iron minerals spread like watercolour paint across the landscape (Credit: Peter Adams/Getty Images)

When the minerals meet air, they redden, and then darken as they collect in deeper waters (Credit: Peter Adams/Getty Images)

The Carajas Mine in Brazil, one of the largest iron ore mines on the planet (Credit: Getty Images)

Like the whorl of a giant fingerprint: Bingham Canyon Mine, also known as the Kennecott Copper Mine, Utah (Credit: Getty Images)

The Los Filos gold mine in Guerrero State, Mexico (Credit: Ronaldo Schemidt/Getty Images)

In the Brazilian Amazon, the Esperanca IV informal gold mining camp, near the Menkragnoti indigenous territory Credit: Joao Laet/Getty Images)

Elsewhere in the Amazon, in Peru, a deforested area caused by illegal gold mining in the river basin of the Madre de Dios (Credit: Cris Bouroncle/Getty Images)

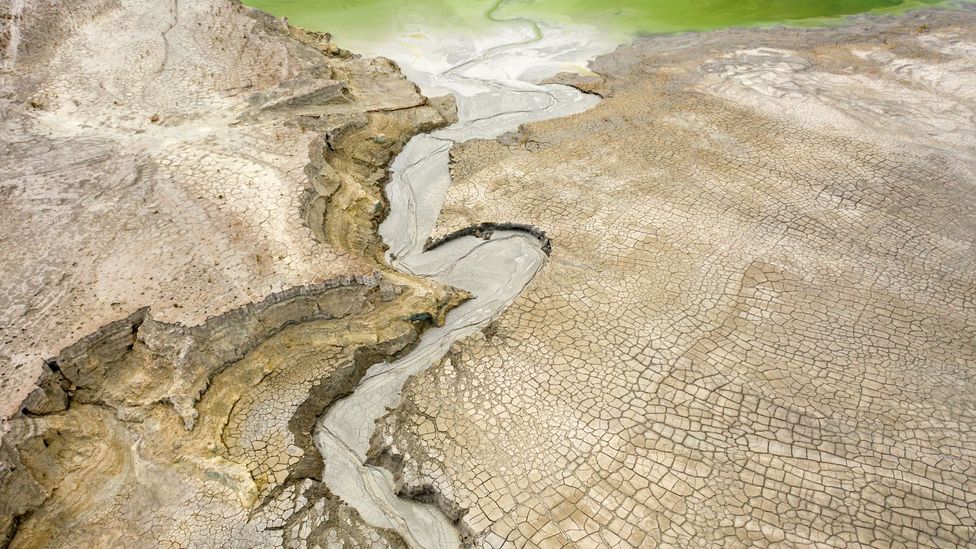

A tailings pond used to store byproducts of copper mining in Rancagua, Chile (Credit: Martin Bernetti/Getty Images)

Copper is one of Chile’s main exports (Credit: Martin Bernetti/Getty Images)

Cracks on a parched surface surround another tailings pond there (Credit: Martin Bernetti/Getty Images)

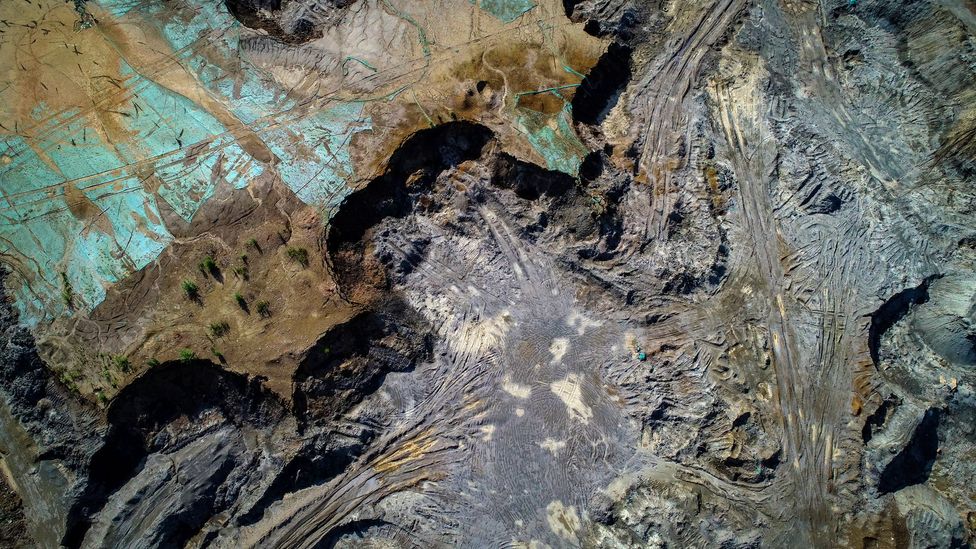

Away from the tailings, vehicle tracks weave around the Chilean copper mine (Credit: Martin Bernetti/Getty Images)

Orange water fans out over the forested landscape near a disused copper-sulphide mine near the village Lyovikha in the Urals, Russia (Credit: Sergey Zamkadniy/Getty Images)

Like the surface of another planet, the abandoned Khrustalny mine in Kavalerovo, Russia, which once produced 30% of the Soviet Union’s tin (Credit: Yuri Smityuk/Getty Images)

The Garzweiler opencast lignite coal mine in Juechen, Germany (Credit: Ina Fassbender/Getty Images)

Lignite coal is a soft fossil fuel made of naturally compressed peat (Credit: Ina Fassbender/Getty Images)

An open coal mine reaches to the horizon near Mahagama, in the Indian state of Jharkhand (Credit: Xavier Galiana/Getty Images)

The Eti Mine Works in Eskisehir, Turkey, where lithium – a key component of batteries – is produced from boron sources (Credit: Ali Atmaca/Getty Images)

Demand for lithium has risen as our demand for electronics and electric vehicles grows (Credit: Ali Atmaca/Getty Images)

The Rossing Uranium Mine in Namibia, one of the largest open pit uranium mines in the world, in the Namib Desert (Credit: Wolfgang Kaehler/Getty Images)

Like a jewellery pendant, a pond at an abandoned magnesite pit near Vavdos village in the mountains of Chalkidiki, Greece (Credit: Nicolas Economou/Getty Images)

The snowy Mir diamond mine in Russia hints at what our descendants may discover. What will they make of these legacies of our consumption? (Credit: Alexander Ryumin/Getty Images)